Chapter 5

Restorative Dental Emergencies

Introduction

Dental surgeons working in dental emergency clinics will encounter dental emergencies on a daily basis. Most of these emergencies usually require some form of restorative care. This chapter covers the diagnosis and management of common conditions requiring emergency restorative care.

Broadly speaking, patients who seek dental emergency care usually complain of pain, swelling(s) and problems with the structural integrity and retention of teeth, fillings and prostheses. One study of patient attendance for emergency care in a British dental teaching hospital showed that most patients complained of oro-facial pain (77%), swelling (22%) or a lost restoration (21%) (Scully, (1995)). Another, community-based study reported that pain and prosthetic problems were the most frequent reasons for consulting an emergency dental hospital department in France (34% and 42% retrospectively) (Roger-Leroi et al, (2007)).

It is essential that the clinician is able to correctly diagnose the presenting condition and carry out effective emergency care in an expeditious manner. It is equally important that every dental emergency clinic adopts a policy for management of emergency walk-in patients or telephone calls. The use of a triage system is invaluable in managing these cases efficiently. Various questionnaires and decision-making ‘trees’ are available to reach sound diagnoses and management decisions. Table 5.1 gives an overview of many conditions requiring emergency or urgent restorative care.

Table 5.1 Summary of most common reasons for seeking emergency restorative care.

This chapter cannot cover every possible situation that could arise but addresses the more common conditions that may present. In view of this, it is important that certain basic principles are adhered to for safe patient management.

General principles

The aetiology and management of restorative dental emergencies is usually relatively straightforward. More serious conditions can present on occasion with similar clinical presentations. It is for this reason in particular that the practitioner should carry out a thorough work up.

All patients should have a thorough history taken, along the lines discussed in Chapter 2.

A thorough clinical examination should be carried out, looking for any teeth that are sensitive to percussion. In addition, tooth mobility, periodontal pocketing, caries, soft tissue swelling, fractures, the condition of existing restorations and pulp vitality should all be borne in mind. Appropriate special tests should be obtained according to accepted criteria and must potentially influence patient management to be fully justified.

Pain management

Dental pain, ranging from tooth sensitivity to throbbing, intractable pain, comprises around 20–75% of reasons for seeking emergency dental care. A summary is given in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 Summary of common dental pain conditions requiring emergency restorative care.

Dentine hypersensitivity

Dentine hypersensitivity is defined as a short, sharp pain that arises from exposed dentine in response to a stimulus, commonly cold, hot, evaporative, tactile, osmotic or chemical that cannot be attributed to any other dental cause. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. Prevalence is variable but has been estimated to be between 4% and 57%. However, in patients with periodontitis, it can be as high as 60–80%. Dentine hypersensitivity presents as a severe problem in 1% of patients.

Distribution occurs mostly in the 30–40 year age group and is more common in women than men. Any age group and any tooth can be affected. It commonly arises at the cervical margins on the labial and buccal tooth surfaces. Not all exposed dentine surfaces are sensitive. Sensitivity is initiated when the smear layer has been removed, opening the dentinal tubules. Tooth substance loss due to erosion and attrition may also be implicated.

Following a correct diagnosis, treatment follows two distinct pathways, in-surgery treatment and home treatment, followed by review should the condition not resolve.

In-surgery treatments include topically applied desensitising agents such as fluoride as sodium or stannous fluoride. Potassium nitrate can be applied topically as a gel or aqueous solution. Sealants in the form of adhesive resins applied to the areas of sensitive dentine to occlude open tubules may be used.

Other less commonly used or accessible treatments include: iontophoresis in conjunction with fluoride pastes. Laser treatment has been employed in some cases (Nd:YAG). In-home treatment includes improved oral hygiene techniques and the use of non-abrasive dentifrices, the use of desensitising toothpastes and fluoride mouthwashes.

Reversible pulpitis

Reversible pulpitis presents as summarised below:

- Pain with hot, cold and sweet.

- Pain is short and sharp, mediated by the A delta fibres (see Chapter 8).

- Pain that ceases when the stimulus is removed. Can be difficult to locate.

- Electric pulp test (EPT) within normal limits but can be hyperalgesic.

- Percussion test within normal limits. There will be pain if dentine is cut.

- Radiographs may show caries or an extensive restoration.

Management

- Check the occlusion and remove non-working facets.

- Caries removal where appropriate and place a sedative dressing. This may be a calcium hydroxide (setting) liner and glass ionomer cement (GIC) placed to provide an effective seal.

- Advise to attend for further assessment of restorative needs and definitive treatment.

Irreversible pulpitis

- Pain with hot, cold and sweet stimuli.

- Pain is persistent, C fibre pain. Lasts minutes or hours after the stimulus has been removed.

- Pain is spontaneous, throbbing in character, can disturb sleep, is often difficult to localise, eased with analgesics.

- In advanced cases, cold can ease the pain and heat will make it worse.

- EPT is not helpful in early cases. Can be within normal limits, the responses can be variable, delayed or early.

- There is no pain if the dentine is cut if the coronal pulp is non-vital.

- Percussion tests are within normal limits.

- Radiographs may show deep caries or large restorations and occasionally early widening of the apical periodontal membrane space.

Management

Ideal treatment consists in accessing the pulp chamber and the complete extirpation of the coronal and radicular pulp. This should be carried out under the cover of rubber dam. The pulp should be completely removed from the root(s) and pulp chamber, the root canals measured for working length, the root canal(s) shaped and cleaned using a solution of sodium hypochlorite at a dilution between 0.5% and 5%. The pulp chamber and root canal(s) should then be dried and sealed with a dry sterile cotton wool pledget and the tooth sealed with a dressing using GIC. The danger if the procedure is incompletely performed is laceration of the pulp contents, its incomplete removal resulting in further pain and the possible introduction of sepsis. At the least it would create difficulties for the subsequent treatment and in particular the successful use of local anaesthesia, due to increased pulpal inflammation.

An alternative treatment modality is to remove the coronal pulp and the coronal portions of the radicular pulp, irrigation with chlorhexidine solution and the placement of an antibiotic or corticosteroid dressing on a cotton wool pledget with the introduction of the dressing material into the coronal portion of the root canal system. A guide to which treatment to use is to look for the top of the radicular pulps and if there are bleeding surfaces, then it would be reasonable to use this compromise system. If there is still necrotic tissue within the root canals, then the canals should be accessed as first described.

Post-treatment pain may be due to several different causes:

- The tooth may be over-filled and ‘high’ in the bite.

- Laceration of vital pulp tissue, incomplete extirpation, over-instrumentation and trauma to the periapical tissues.

- Inadvertent extrusion of sodium hypochlorite solution into the periapical tissues.

- Perforation of the root or coronal walls.

- Unrecognised aberrant root canal.

It is essential that the root canal system is effectively sealed to prevent contamination and/or re-infection. If pain persists after initial treatment, then further irrigation of the root canal system and perhaps further instrumentation will be required, accompanied by further irrigation with hypochlorite solution or chlorhexidine solution.

Infections and soft tissue problems

Acute periapical abscess

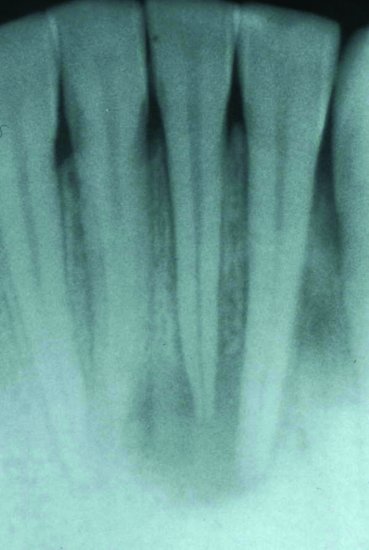

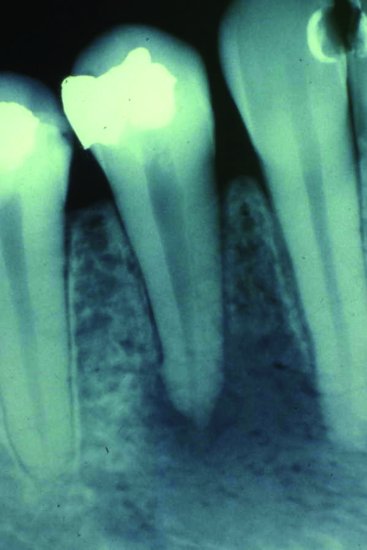

Irreversible pulpitis progresses to an acute apical periodontitis and then to acute periapical periodontitis (Figures 5.1 and 5.2). This is a dynamic change and in the early stages of each condition a differential diagnosis can be difficult to elucidate. There are changes in the radiographic appearance, from a slight widening of the periodontal membrane shadow to a well-marked area. The tooth will become very tender and may show extrusion from the socket with increasing mobility. There will be an associated soft tissue swelling. The tooth will be non-vital. This is very important in the differential diagnosis between an acute apical abscess (non-vital) and a lateral periodontal abscess in which the pulp will usually be vital on testing.

Figure 5.1 Periapical view showing an extensive area of rarefaction at the apices of 31, 32. This lesion was associated with a sinus draining through the skin covering the chin.

Figure 5.2 Periapical radiograph showing periapical rarefaction in a case of acute apical periodontitis.

Management

Drainage is the key, initially by opening up the root canal system and allowing drainage ‘through’ the tooth. The resulting drop in pressure will ease the pain. In the presence of an intra-oral swelling that is fluctuant, drainage may need to be established by incision. A large extra-oral swelling or a spreading cellulitis in the neck associated with pyrexia and dysphagia requires referral to a department of oral and maxillofacial surgery for urgent treatment as the condition can rapidly become life-threatening.

Local anaesthesia can be difficult to achieve by local infiltration and a regional nerve block may be more successful.

Acute periodontal abscess

A periodontal abscess is an acute, destructive process in the periodontium that results in the localised collection of pus communicating with the oral cavity through the gingival sulcus or other periodontal sites not arising from the tooth pulp.

Aetiology

Cases of acute periodontal abscess tend to occur in a pre-existing periodontal pocket. If drainage through the pocket is blocked, then there is a build up of pus. This results in the recognisable clinical signs. Periodontal abscesses can also occur following professional mechanical tooth cleaning if there is inadequate instrumentation of the base of the periodontal pocket or furcation area.

A compromised immune response may predispose a patient to periodontal pocket formation. Multiple periodontal abscesses are seen typically in poorly controlled diabetic patients, for example.

Clinical features

Pain, oedema and erythema of the involved periodontal tissues may all be seen. If there is systemic involvement, lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis may be detected. The tooth involved is tender to the bite and tender to percussion. Periodontal pocketing is usually found, the tooth might be extruded slightly from its socket and a discharging sinus may be evident.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of periodontal abscess is from the history and examination. Radiographs are helpful in confirming the diagnosis; commonly a radiolucency in the lateral aspect of the periodontium is seen. If the infection is sited on either the buccal, palatal or lingual aspect, little radiographic evidence may be seen.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis must be made between an acute apical periodontitis and an acute periodontal abscess as there are similar signs and symptoms in both conditions. They differ in that a tooth with an acute periodontal abscess often is vital and is painful to lateral percussion. A tooth with an acute apical periodontitis is usually non-vital and tender to vertical percussion. Radiographic changes are seen apically. Conversely, the radiographic changes, if seen, are lateral in the periodontal membrane space in a periodontal abscess. A sinus, if present, is found near the tooth apex in the case of acute periodontitis, and between the apex and the gingival margin in the case of acute periodontal abscess. Drainage and antibiotic therapy are the mainstays of treatment.

Treatment of a gingival abscess or an acute periodontal abscess

The dental surgeon should give a local anaesthetic, establish drainage and debride the lesion. In the case of a gingival abscess, blade incision is used to establish drainage. Drainage for the periodontal abscess is achieved with an external incision or by curette via the pocket. Care should be taken not to over-instrument the root surface as this decreases the prospects for reattachment. After drainage is established, the area should be irrigated with warm saline solution or water. For a periodontal abscess, antibiotics should be prescribed if the patient is experiencing malaise, lymphadenopathy or is febrile. Analgesics may be prescribed for pain. After treatment of an acute abscess, the patient should return the next day. The clinician should evaluate the area, to assess the need for further treatment (such as surgery) after the acute symptoms have resolved.

Acute gingivitis

Gingivitis can be defined as inflammation of the gingivae. This is caused by a build up of plaque. Plaque is a biofilm formed on the tooth surface consisting of oral bacteria (Streptococcus, Actinomyces, gram-positive and gram-negative anaerobic rods) that are embedded in a polymer matrix of bacterial and salivary origin. Plaque forms a layer over the surfaces of the gums and teeth in stagnant and protected surfaces. The bacteria in plaque release toxins, enzymes and metabolic products that cause local inflammation and damage to the gingivae; hence, gingival bleeding particularly on toothbrushing is one of the signs of gingivitis. The removal or inhibition of microbial plaque can prevent development of gingivitis.

A large proportion of the population (70–90% of the adult population), is estimated to have some degree of gingivitis. Gingivitis is more prevalent in older adults, although it can be found at any age after tooth eruption.

Treatment of gingivitis takes three forms:

1. Physical removal of plaque by efficient toothbrushing, or professional mechanical tooth cleaning.

2. Chemical inhibition of bacterial plaque formation using mouthwashes containing chlorhexidine solution.

3. Dental health education and oral hygiene instruction to correct deficiencies in cleaning techniques are important.

Clearly, management can only be initiated in the dental emergency clinic and patients require careful follow-up by the patients’ regular practitioner.

Acute periodontitis

Periodontitis is a sequel to untreated gingivitis. It is characterised by inflammation and loss of bone support for the tooth and the breakdown of the periodontal attachment. The teeth become less securely attached and untreated periodontitis carries a risk of tooth loss. People with diabetes may have an above-average chance of developing periodontitis.

If gingivitis is prevented or treated, the development of periodontitis is prevented.

Complications of gingivitis

The symptoms of mild gingival disease are bleeding gums and halitosis. This may progress to spontaneous bleeding with loss of bone, periodontal attachment loss and eventual tooth loss. There is also the risk of localised infection within the periodontal membrane – a periodontal abscess.

There are also more serious potential consequences. The barrier function of the gingival tissue is reduced in people with gingivitis. This means that toxins and bacteria may enter the bloodstream through the gingivae. The implications of this can be serious:

- Dental plaque bacteria, after entering the bloodstream, can become trapped in atheromatous plaques within the arteries. People with severe periodontal disease are possibly more likely to have an acute myocardial infarction or a stroke than those without it.

- Patients with lung conditions may find that periodontal disease increases their chance of a respiratory tract infection.

- Periodontal disease in pregnancy is possibly a predictor of low birth weight, as plaque bacteria are thought to produce cervical/u/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses