Pigmented Lesions

Pigmented oral mucosal lesions can be divided into two fundamental groups: those containing melanin and those containing other pigments. The latter would include discolorations associated with drug ingestion, metal implantation, and heavy-metal ingestion/intoxication. Breakdown products from extravascular blood due to trauma or blood dyscrasias (see Chapter 4) can also discolor oral mucosa. Pigmented lesions, which range from trivial to serious (melanoma), can be confused with each other clinically, necessitating careful evaluation.

Melanocytic Lesions

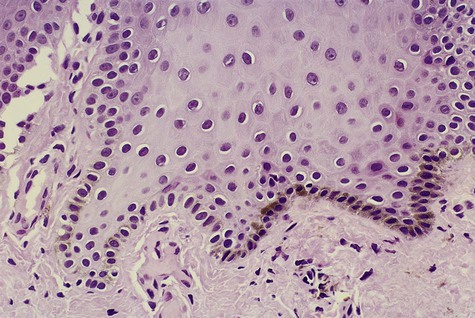

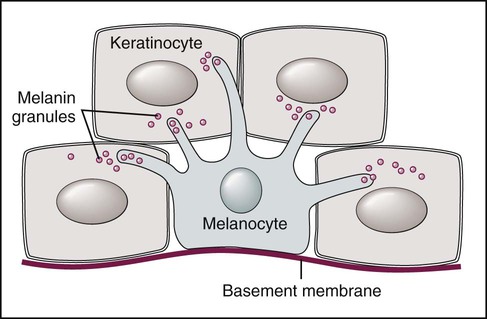

Melanocytes are found throughout the oral mucosa but go unnoticed because of their relatively low level of pigment production (Fig. 5-1). They appear clear with nonstaining cytoplasm on routine histologic preparation. When focally or generally active in pigment production or proliferation, they may be responsible for several different entities in the oral mucous membranes, ranging from physiologic pigmentation to malignant neoplasia.

Note dendritic processes of melanocyte and melanin transfer to keratinocytes.

Physiologic (Ethnic) Pigmentation

Clinical Features

Physiologic pigmentation is symmetric and persistent and does not alter normal architecture, such as gingival stippling (Fig. 5-2). This pigmentation may be seen in persons of any age and is without gender predilection. Often the degree of intraoral pigmentation may not correspond to the degree of cutaneous coloration. Physiologic pigmentation may be found in any location, although the gingiva is the most commonly affected intraoral tissue. A related type of pigmentation, called postinflammatory pigmentation, is occasionally seen after mucosal reaction to injury (Fig. 5-3). Occasionally in cases of lichen planus, areas surrounding active disease may eventually show mucosal or postinflammatory pigmentation.

Smoking-Associated Melanosis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Clinical Features

The anterior labial gingiva is the region most typically affected, where brownish color can vary from subtle to obvious. Palate and buccal mucosal pigmentation has been associated with pipe smoking. In India, the use of smokeless tobacco forms has been linked to oral melanosis, particularly among alcoholics. In smoking-associated melanosis, the intensity of pigmentation is time and dose related (Fig. 5-4).

Oral Melanotic Macule

Clinical Features

Oral melanotic macule (or focal melanosis) is a focal pigmented lesion that may represent (1) an intraoral freckle; (2) postinflammatory pigmentation; or (3) macules associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Bandler syndrome, or Addison’s disease (see Box 5-1).

When melanotic macules (freckles) are seen in excess in an oral and perioral distribution, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and Addison’s disease should be considered (Box 5-2; Figs. 5-5 to 5-8). Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a condition that is inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern. In addition to ephelides or melanotic macules, intestinal polyposis is present. These polyps are regarded as hamartomas without, or with very limited, neoplastic potential. They usually are found in the small intestine (jejunum) and may produce signs and symptoms of abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and diarrhea.

Differential Diagnosis

These oral pigmentations must be differentiated from early superficial melanomas. They may be confused with blue nevi (palate) or amalgam tattoos. If they are numerous, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Addison’s disease, Bandler syndrome, and Laugier-Hunziker syndrome may be possible clinical considerations (Box 5-3).

Café-au-Lait Macules

Café-au-lait macules are discrete melanin-pigmented patches of skin that have irregular margins and a uniform brown coloration. They are noted at birth or soon thereafter and may also be seen in normal children. No treatment is required, but they may be indicative of a syndrome of greater significance (Box 5-4).

Individuals with six or more large café-au-lait macules (>0.5 cm diameter prepubertal, >1.5 cm diameter postpubertal) should be suspected of having neurofibromatosis (NF) (Fig. 5-10). Two forms of this autosomal-dominant disorder affect 100,000 people in the United States: neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1; previously called von Recklinghausen’s disease) and neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2; formerly known as acoustic neurofibromatosis). Although some overlapping features are known, the two conditions are distinct clinically and genetically. NF1 is a relatively common disorder affecting 1 in 3000 individuals. Approximately 50% of cases are inherited, and the remainder represent spontaneous new mutations. The condition is characterized by numerous neurofibromas of the skin, oral mucosa, nerves, and central nervous system, and occasionally the jaw. Axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign) accompanied by the presence of six or more of these macules is regarded as pathognomonic for NF1. The genetic abnormality involves the neurofibromin gene located on chromosome 17q11.2. This tumor suppressor gene encodes for neurofibromin protein, which downregulates the function of the p21ras protein. NF2 is characterized by bilateral acoustic neuromas, one or more plexiform neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules. The condition is caused by a mutation in the NF2 tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 22q12 that encodes for the merlin protein, which, in turn, shows structural similarity to a series of cytoskeletal proteins. The normal function of merlin is not known.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses