Chapter 5. Maintaining dental pulp vitality

H.F. Duncan

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Summary55

Introduction55

Pulp–dentine complex55

Pulp response to irritants56

Management of deep caries59

Regenerative developments60

Learning outcomes64

References64

SUMMARY

Maintaining pulp vitality and preventing apical periodontitis is a founding principle of operative dentistry and endodontics. The vital pulp as part of the pulp-dentine complex has an array of defensive attributes which aim to protect itself against irritation. Knowledge of these irritants and the pulpal response is essential to prevent damage and to harness the natural defences. Recent developments in material science and molecular biology have led to a better understanding of tertiary dentinogenesis and greater predictability in treating deep caries and pulpal exposures.

INTRODUCTION

Clinicians should be aware that the best root canal filling is healthy pulp tissue. It should not be assumed that every damaged pulp must be extirpated and that pulp conservation is an unsatisfactory procedure. Therefore, preserving the pulp should be encouraged within the discipline of modern endodontics; it is more conservative, more biologically acceptable and less technically demanding than pulpectomy.

PULP-DENTINE COMPLEX

The dental pulp is in the centre of the tooth and is the tissue from which the dentine was formed during tooth development. It remains throughout life and provides nourishment for the odontoblasts that line its surface. These odontoblasts have long processes that may extend partly1 or completely to the amelodentinal junction. 2 The tubules around and beyond the odontoblast processes are normally patent and filled with tissue fluid. When irritants are applied to the distal ends of the dentinal tubules, the odontoblasts will form more dentine, within tubules as intratubular dentine, leading to tubular sclerosis, or within the pulp as tertiary dentine. Sclerosis is a mechanism designed to protect the pulp and results in a more highly mineralized dentine at the distal extremities of the odontoblast processes. Two types of tertiary dentine are recognized, reactionary dentine formed by existing odontoblasts in response to mild irritation, or reparative dentine formed by newly recruited odontoblasts in response to severe irritation and odontoblast death. 3,4 Reparative dentine formation also occurs after pulp exposure when a dentine bridge is formed. If tertiary dentine is formed quickly, in response to more severe stimuli, the tubular pattern is less regular than if it is formed slowly, in response to mild stimuli. The tertiary dentine formed is, generally, confined to the tubules affected by the carious lesion. In addition to hard tissue deposition, another defensive feature in response to irritation is outward movement of fluid through the tubules during pulpal inflammation; this will reduce the inward movement of toxins.

The pulp and dentine can thus be regarded as one interconnected tissue, the pulp-dentine complex. This is normally protected from irritation by an intact layer of enamel. When enamel is breached by caries, erosion or operative procedures, the pulp is at risk. In a young patient, the tubules are wider and the pulp closer to the surface, so a similarly sized breach of enamel will have a greater effect on the pulp than that in an older patient. The greater the area of exposed dentine, the greater is the effect on the pulp. Therefore, the potential damage of crown preparations, extensive tooth wear and large cavities is greater.

PULP RESPONSE TO IRRITANTS

The pulp response to irritation is inflammation and formation of tertiary dentine and tubular sclerosis; these hard tissues attempt to wall off the irritants from the pulp, which will then become less inflamed. It has been shown that if buccal cavities are prepared in otherwise sound teeth and are left open to salivary microbial contamination, the pulp underneath the exposed tubules becomes inflamed. 5 If the irritant is removed and a restoration which prevents microleakage is placed, the pulpal inflammation subsides and tertiary dentine is formed; therefore, damaged pulps have the capacity to recover. 6

PULP IRRITANTS

The dental pulp may be affected by a variety of stimuli, which can be broadly classified as being either microbial, chemical or mechanical in origin. These irritants, for example mechanical and microbial, may act in combination to provoke pulpal inflammation.

Microbial

Dental caries

This has been regarded as the main cause of pulpal injury as it has been classically demonstrated that in the absence of bacteria, pulpal inflammation does not occur. 7 In the early carious lesion the odontoblasts respond by hard tissue deposition. 8,9

As the carious lesion progresses, the enamel surface breaks down and bacteria enter the dentine. The rate of decay usually then accelerates. The lesion may be divided into zones: an outer zone of destruction, a middle zone of bacterial penetration and an inner zone of demineralization. The zone of destruction contains dentine partially destroyed by proteolytic enzymes from the mixed microbiota. The dentinal tubules and shrinkage clefts are filled with microorganisms. This carious dentine can be readily removed with hand excavators in active lesions and often has a light colour. In slowly progressing or arrested lesions, this dentine is darker and has a harder consistency.

The next zone, the zone of bacterial penetration, contains microorganisms within the dentinal tubules. The structure of the dentine, when examined in a demineralized histological section, is otherwise normal. Some tubules are deeply infected while others contain no microorganisms. A variety of microorganisms from this zone have been identified by culturing techniques – Lactobacilli, Streptococci and Actinomyces species. 10,11 More recently, molecular techniques have suggested that the microbiota is more complex than previously thought with many uncultivable species. 12 Deep carious dentine has been shown to contain predominantly anaerobic bacteria including Propionibacteria, Prevotella, Eubacteria, Arachnia and Lactobacilli.13.14. and 15. Ahead of the zone of microorganism penetration is a zone of demineralization, frequently considered to be devoid of bacteria because the conditions for bacterial survival are too unfavourable; however, small numbers of anaerobic bacteria have been demonstrated in this zone. 16

When dental caries affects the superficial dentine, initially localized inflammation is evident in the pulp. The dentine-pulp complex responds by intratubular dentine deposition leading to tubular sclerosis and by tertiary dentine deposition. Therefore, after a short interval the pulp is likely to recover and be of normal histological appearance. 17 No foci of inflammatory cells can be observed in the pulp until caries has penetrated to within 0.5 mm. 18 As the early dentine carious lesion progresses, the sclerotic zone of dentine becomes demineralized and the lesion subsequently advances into the tertiary dentine. When bacteria invade this dentine, severe pulp changes such as abscess formation often occur. Therefore, until the caries is very deep, the pulp is likely to be no more than reversibly damaged. Treatment should normally consist of removal of carious dentine and insertion of an effective restoration. This has been shown to result in recovery of the pulp. 6 Since it is difficult to assess accurately the histological state of the pulp from signs and symptoms, it is important to monitor teeth with deep caries.

The pulp is not infected until late in the carious process, typically when the tertiary dentine is invaded. Infection of the inflamed pulp is localized to necrotic tissue in a pulp abscess. 19 Wider infection of the pulp only occurs after necrosis.

Bacterial microleakage

Bacterial microleakage occurs around all restorations to a greater or lesser degree. 20 The bacteria from the oral cavity colonize the space around the restoration after its placement, rather than surviving from the time it was placed. The lack of importance of bacterial contamination at the time of cavity preparation has been shown in studies of pulpal exposures. 21,22 There is a good correlation between bacterial leakage around restorations and pulpal inflammation. 23,24

The pulpal responses to irritation from bacterial microleakage are inflammation, tubular sclerosis and formation of tertiary dentine, so that after some months the bacteria ceases to irritate. 25 Nevertheless, measures should be taken to prevent pulp damage during this initial period. These consist of placing a cavity lining or base, the application of cavity varnish if appropriate, the use of a dentine-bonding agent and etching of enamel, or the use of an adhesive cement. In operative dentistry, the main reason for placing a cavity lining is to prevent damage to the pulp from bacterial leakage around restorations. Former reasons such as material irritancy or thermal protection have been severely criticized. 26,27

In many instances, the choice of lining material in deep cavities without pulpal exposures would appear to be a matter of operator preference. Cements based on calcium hydroxide, glass ionomer, zinc phosphate or zinc oxide-eugenol would all appear to be satisfactory under amalgam, and have been widely used. Zinc oxide-eugenol cement has the benefit of prolonged antibacterial activity. Under resin-based restorative materials, linings are rarely placed as dentine-bonding agents are often adequate; zinc oxide–eugenol cement is inappropriate, unless separated by a covering layer of alternative cement (e.g. glass ionomer), as otherwise the eugenol may plasticize the resin. The durability of some calcium hydroxide cements has been questioned, particularly if the overlying restoration has an imperfect seal. 28,29

Chemical

Dental materials

Historically, dental materials have been considered to exert an irritant effect on the pulp.30.31. and 32. However, during the last 25 years, much of the earlier work on the irritancy of various materials has been brought into question.20.24.33.34.35. and 36. For example, composite resin has been regarded as irritant to the pulp, but the blandness of this material has now been demonstrated together with the important contribution of bacterial leakage to pulp reaction. 36,37 Composite resin contracts when polymerized causing a gap to occur between the resin and the tooth, into which bacteria penetrates; inflamed pulps have been found in teeth with bacteria in the gap. 20,38 From a clinical standpoint, both etching enamel margins and dentine bonding are considered necessary to prevent a pulpal inflammatory reaction. Composite resins are continually evolving and appear to prevent leakage if carefully placed, demonstrating good clinical success.39.40. and 41. However, some concern remains regarding their long-term bond to tooth substance. 42 Generally, it is accepted that most restorations ‘leak’ to varying degrees so prevention of microleakage is more important than the chemical irritancy of the material itself. Clinically, a restoration should be placed which either bonds to tooth tissue or if not, a lining should be placed under the restoration which prevents leakage.

Pulp damage may occur in relation to temporary crown materials, again not because of their inherent toxicity but more as a result of marginal leakage and bacterial invasion of dentinal tubules. Temporary crowns should not be used for long periods and they must always be adequately cemented. 26,43 Another way to reduce pulp damage during temporary crown placement is to ‘block’ the dentinal tubules and prevent bacterial ingress, by placing bonding agent prior to cementation of the temporary crown.

Bleaching

Vital bleaching procedures are an increasingly prominent aspect of modern dentistry and tooth sensitivity is a common side-effect of such procedures. Sensitivity was experienced in 15–65% of patients undergoing bleaching46,47 but only a small number of patients experienced severe symptoms. 48 Chairside bleaching procedures, which are often associated with a rise in pulpal temperature, are associated with a higher incidence of sensitivity than home bleaching. 49 The symptoms are usually reversible and generally resolve 1–2 weeks after the end of the procedure46.48. and 50. but it may be more severe if the patient has a previous history of sensitivity. 46,48 The mechanism appears to be that the peroxide diffuses through the enamel and down the dentinal tubules into the pulp resulting in inflammation. However, irreversible pulp damage has not been observed51 even when heat-generating bleaching techniques were employed. 52

Mechanical

Operative dentistry

The preparation of dentine with rotary instruments can have a damaging effect on the pulp unless measures are taken to minimize injury. Cavity preparation without water-spray causes significantly more pulp damage than when water-spray is used. 53,54 The operator must verify that the water-spray is continuously directed at the revolving bur. If the spray is obstructed by tooth structure or excess pressure is applied to the bur during use, pulp damage may occur. 55 High speed instrumentation is acceptable provided adequate water coolant is used; the use of air coolant alone is considered unsatisfactory.

The area of dentine prepared can have a profound effect on the pulp response. The more tubules exposed, the more routes there are for irritants to reach the pulp. Therefore, pulpal damage results not because of the operative procedure per se, but because the preparation exposes avenues for microbial penetration. Dentinal fluid outflow counteracts this by acting as a flushing mechanism to prevent the inward movement of irritants. Small cavities are likely to be less damaging to the pulp than large ones. In addition, in a small cavity prepared to treat a carious lesion, most of the exposed dentinal tubules would have been blocked by tubular sclerosis as a result of the caries. The deeper the cavity, the greater is the potential for damage: the pulp is closer, odontoblast processes may have been cut, more tubules will have been exposed, and the deeper dentinal tubules have a larger diameter. However, no correlation between thickness of remaining dentine and pulp damage has been shown. 53,56 Only when cavities are very deep, with the remaining dentine less than 0.3mm thick, does some pulp damage occur. 54 Prolonged drying of cavities causes odontoblast aspiration, i.e. their cell bodies move into the dentinal tubules, but there is no permanent damage to the pulp. 57

Crown preparations, due to the number of tubules exposed, are potentially the most damaging to the pulp, with irreversible damage the occasional result; 33 10 and 15% of crowned teeth have been shown to lose vitality over a 10 year period. 58,59 When local anaesthetics containing adrenaline are used for crown preparation, the pulp is at particular risk of damage because of vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow. 60,61 The reduction in blood flow means that the pulp is unable to regulate its temperature control and other physiological defences.

The pulp response to the use of lasers for cavity preparation has been reported to have no long-term adverse effects.62.63.64. and 65. Many of the beneficial properties of a laser are due to its thermal properties, so unless rigorous safety parameters are established for every type of laser equipment, there is a substantial risk of pulpal damage when they are used to treat the exposed pulp. Damage has been reported when lasers were used directly on the pulp. 66 Whilst other studies have suggested that lasers have no detrimental effects.67.68. and 69.

Trauma

The extent of the damage may range from infraction of enamel through lost cusps to a split tooth that cannot be restored. Direct trauma to the anterior teeth often results in fractures that are horizontal or oblique; 70 while with indirect trauma, fractures are, generally, longitudinal. Trauma to anterior teeth most commonly affects children. These teeth frequently have large pulps and wide dentinal tubules so any injury which exposes dentine can potentially damage the pulp and early treatment is important. Traumatic injuries may also damage the blood supply to the pulp, which as a result may calcify or die.

Exposure of dentine

This may occur due to fracture of part of the tooth, by a defective restoration which fails to cover the entire area of the prepared cavity, or by attrition, abrasion or erosion of the overlying cementum or enamel. In the early period after exposure of dentine by trauma, parafunction or cavity preparation, the pulp is sensitive to stimuli and may become inflamed, particularly if bacteria colonize the exposed dentine and enter the tubules. The pulp responds to the low-grade irritation, as previously described, by hard tissue formation, thereby protecting itself over time and making it less sensitive to stimuli. 71

Cervical sensitivity can occur in undamaged or non-restored teeth, where the gingival tissues have receded and the root dentine is exposed; this is often as a result of vigorous tooth brushing. Without protection the exposed tubules are open and communicate with the pulp. Sensitivity may be reduced by application of potassium oxalate or bonding resins, which not only occludes the tubules but also reduces nerve activity. 71,72 The repair process can be undermined by further assault either by parafunction, further abrasion or erosion. This is particularly problematic in patients who continue to erode their teeth either with acid from drinks and foods, or from regurgitation. 26,73

Function/parafunction

The effects of occlusion on the pulp are negligible as long as a protective covering of enamel remains intact. When enamel is breached, the dentine is exposed and irritants have a direct pathway to the pulp via the dentinal tubules. The pulp will protect itself from damage by tubular sclerosis and tertiary dentine deposition. Loss of enamel and exposure of dentine is unlikely during normal function but can occur by attrition after extended periods of parafunction. If the parafunction is particularly severe, continued sensitivity can result due to continual wear of the dentine, rather than due to any direct irritation by occlusal forces. Parafunction can also result in cuspal flexure which stimulates the pulp by outward movement of dentinal fluid; this is exaggerated considerably if a ‘crack’ in the tooth develops. 74

MANAGEMENT OF DEEP CARIES

With the treatment of any carious cavity in dentine, it is accepted that the margins and the amelodentinal junction in particular, must be caries-free. However, there has been less agreement over whether all carious dentine overlying the pulp should be removed.75.76. and 77. In a tooth with a deep carious lesion, which is considered to have a healthy pulp, partial caries removal appears to be preferable to complete caries removal and the risk of pulp exposure. 78

A traditional view prevails that if any carious dentine remains, the carious process will continue. An opposite view, supported by clinical evidence, is that if a small amount of caries is left on the pulpal aspect of the cavity and the margins are clear, the lesion can arrest. It appears that the change in environmental conditions and a reduction in bacterial load render the remaining carious lesion inactive. Visually, the yellow carious dentine will darken and dry over time. 79,80 However, the latter technique is subjective and lacks precision as the definition of a small amount of caries will vary from one operator to another, and when does a little become an unacceptably large amount?

There are two recognized approaches to partial caries removal, indirect pulp therapy and stepwise excavation. The former is a one-stage procedure in which most, but not all of the caries is removed prior to placement of a permanent restoration. This technique is gaining momentum as the treatment of choice for advanced caries in deciduous teeth.81.82. and 83. In comparison, stepwise excavation is a two-step approach in which a small amount of carious dentine is left at the first visit and the tooth dressed, prior to the tooth being re-entered after a period of several months. This technique has also been shown to be successful in reducing the frequency of pulpal exposure. 76,84 The principal of a two-stage approach is that the reaction to the treatment can be visually assessed and the remaining decay removed without an increased risk of pulp exposure. This is dependent on tertiary dentine deposition over the intervening period but this may be difficult to assess, as the volume of tertiary dentine deposited will vary from patient to patient. These differing approaches raise the question as to whether a second intervention is really necessary. At present, this is yet to be fully clarified, as indirect pulp therapy is principally carried out in the United States and stepwise excavation mainly in Scandinavia. In addition, although indirect pulp therapy can be carried out on permanent teeth, most of the research to date has been on deciduous teeth. Therefore, data comparing the two techniques are not available.

Clinical opinion is in conflict with scientific evidence when deciding if a cavity is caries-free. In one study, only 64% of clinically hard dentine was bacteria-free; 85 therefore, in a third of teeth where the clinician thought there was a clean cavity floor, the diagnosis was wrong. Dyes which stain the superficial infected dentine but not the deeper demineralized non-infected dentine have been advocated to address this problem. 86 However, the use of dye may lead to excessive removal of carious dentine, as all the remineralizable dentine may not be conserved. 87

Light coloured dentine is usually indicative of more active caries but a deep lesion may extend into dentine modified by tubular sclerosis, dead tracts or into tertiary dentine. These are darker than normal dentine, but must not be regarded as carious simply because of their colour. If carious dentine is left in a cavity, the clinician may be unaware as to whether it has invaded the pulp. If the pulp is already inflamed, placing a permanent coronal restoration such as a crown will be an expensive mistake as the crown may need to be modified or destroyed when root canal treatment is needed later. If removal of all the cariously infected dentine leads to the pulp, then root canal treatment is appropriate and should not be deferred, except in certain situations where pulpotomy may be indicated (see later).

Following removal of the carious dentine, a protective lining may be placed in a very deep cavity; hard-setting calcium hydroxide materials, which stimulate pulp repair, have traditionally been used. The use of a liner is dependent on the proposed restorative material and the thickness of dentine remaining over the pulp. The previously held view that liners/bases prevented thermal and chemical damage to the pulp have been discredited with the main reason for failure and sensitivity attributed to microleakage around the restoration. 20 Linings are rarely placed under resin restorations as the entire cavity can be etched and a dentine bonding agent placed to seal the cavity. 38 However, doubts remain regarding the long-term efficacy of resins in preventing microleakage41 and, therefore, whether they provide an adequate seal in deep cavities. Due to their biological properties as pulp capping agents, calcium hydroxide cements are still the material of choice if the thickness of dentine remaining over the pulp is judged to be less than 0.5 mm. However, substantial washout of calcium hydroxide linings/bases under amalgam restorations occurs; 28,29 this may be due to the surface seal not offering long-term protection against bacterial microleakage. For this reason, an antibacterial liner/base should be placed over the calcium hydroxide; zinc oxide–eugenol or glass ionomer cements are both effective for this purpose.

MANAGEMENT OF PULP EXPOSURE

Exposure of the dental pulp can occur as a result of caries, trauma or accidently during cavity preparation. In traumatic and accidental exposures, the pulp can be regarded as being normal prior to the injury. Treatment is usually by pulp capping or partial pulpotomy and provided that treatment is not unnecessarily delayed, a good outcome can be achieved. 88 With a carious exposure, there will be varying degrees of inflammation present in the pulp. This is due to the sustained bacterial onslaught. Inflammation of the pulp has a marked effect on the outcome of vital pulp therapy. 89,90

Pulp capping

Direct pulp capping is as a procedure in which the pulp is covered with a protective material directly over the site of the exposure. The pulp wound should be cleansed of debris and the haemorrhage arrested by applying pressure using sterile paper points or cotton wool; saline and sodium hypochlorite solution can also be useful. When the wound is dry, the pulp capping agent should be placed over the exposure, followed by a zinc oxide–eugenol or glass ionomer as a base and then a permanent restoration. Delay in placing the permanent restoration reduces the prognosis of the procedure91 due to the likelihood of microleakage. 20

Partial pulpotomy

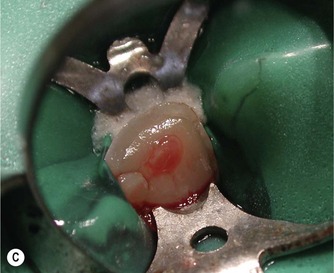

The traditional method involves removing the coronal pulp and placing the pulp dressing on the radicular pulp. A variation of pulpotomy was developed for treatment of traumatized anterior teeth22 which is more conservative and involves removal of the superficial layer of damaged and/or inflamed pulp tissue prior to application of the base/liner. This is advantageous as the superficial damaged tissue is removed, which should encourage healing, and also space is created which allows the pulp dressing to be retained within the dentine. The procedure is similar to pulp capping. It involves cutting a small 2 mm deep cavity into the pulp with an air turbine under water-spray, placing the pulp dressing and covering it with a base and then a coronal restoration (Fig. 5.1).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 5.1

(A) Traumatized, fractured maxillary incisors. (B) The pulp of the maxillary right lateral incisor is exposed. (C) Rubber dam placed to isolate the maxillary right lateral incisor. (D) Partial pulpotomy, 2 mm of pulp tissue was removed with a diamond bur in a high-speed handpiece. (E) MTA placed into the partial pulpotomy ‘cavity’. (F) Immediately after placement of a permanent restoration.

From Duncan et al 200888 with permission of Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd.

|

Choice of material

Calcium hydroxide has been established as the gold standard pulp capping/ partial pulpotomy material over the last 50 years.94.95.96.97.98. and 99. Resins have been investigated as alternatives but they have, generally, been dismissed as not matching the performance of calcium hydroxide. 100,101 Over the last 10 years, Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) has emerged as the material of choice for vital pulp therapy. 102,103

The mechanism of both calcium hydroxide and MTA appears to be the dampening of pulpal inflammation, providing an environment conducive to repair. Thereafter, bioactive molecules are liberated in the dentine which stimulate differentiation of pulpal stem cells and also further control the inflammatory response; this allows the pulp to repair. 97,104 Pulpal stem cells have the ability to develop into odontoblast-like cells which allows the pulp to regenerate and form dentine bridges across the deficit. The dentine bridge is not formed by calcium from the material, but instead from the underlying tissues. 105,106 With resin-based composite, MTA and hard-setting calcium hydroxide, the bridge forms close to the material; however, with calcium hydroxide powder and water mixes the barrier is formed with an intervening zone of necrosis. 99 The dentine bridges formed under calcium hydroxide are often imperfect with numerous tunnel defects; 107,108 this is in contrast to MTA where tunnel defects are not seen102 (Figs 5.2& 5.3).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses