5

Local anaesthesia in the upper jaw

5.1 Introduction

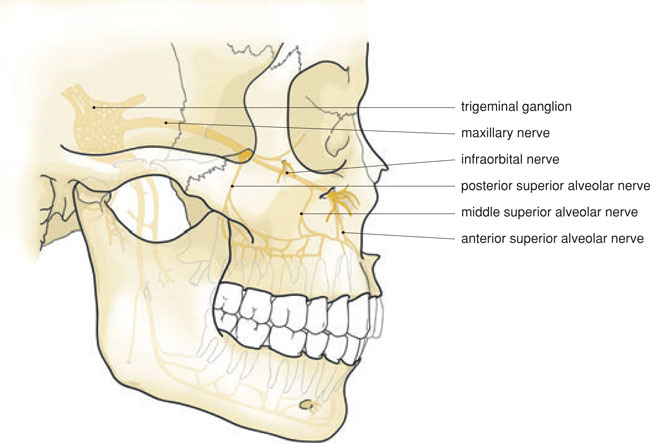

Sensory innervation of the upper jaw arises from the second trunk of the trigeminal nerve, the maxillary nerve. This main branch of the trigeminal nerve leaves the neurocranium via the foramen rotundum, reaches the pterygopalatine fossa and runs straight through as the infraorbital nerve, branching off many times along its course. With regard to local anaesthesia in the upper jaw, the following branches are of importance:

- the greater and lesser palatine nerves;

- the posterior, middle and anterior superior alveolar nerves;

- the infraorbital nerve (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 The course of the maxillary nerve and its main branches.

Thus the main trunk of the maxillary nerve can be reached via the greater palatine foramen, via the infraorbital foramen as well as from high behind the maxillary tuberosity. In practice, high tuberosity anaesthesia is the only practical regional block anaesthesia for almost the entire maxillary nerve. Therefore this regional block anaesthesia technique is used for surgical procedures.

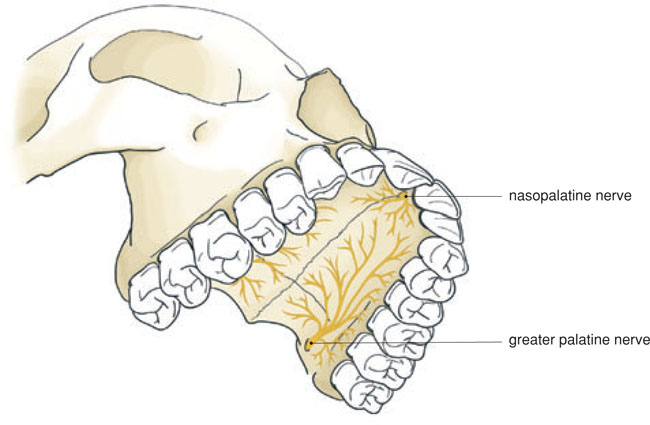

For everyday dental procedures in the upper jaw, infiltration anaesthesia is commonly used. The cortical bone of the outer surface of the upper jaw is relatively thin, which facilitates the diffusion of local anaesthetic fluid. All (buccal) roots of the upper teeth can be reached in this way. The palatine roots of the molars and possibly the premolars are anaesthetised by infiltration anaesthesia of the branches of the greater palatine nerve and those of the nasopalatine nerve. Regional block anaesthesia is also possible via the greater palatine foramen and the nasopalatine canal.

Infiltration anaesthesia of the upper jaw is particularly effective, unless an injection is made into an inflamed area. Regional block anaesthesia of the greater palatine, nasopalatine and infraorbital nerves is equally effective. In cases of regional block anaesthesia using a high tuberosity block, it is usually only the posterior superior alveolar and medial branches that are numbed, but sometimes also the palatine and infraorbital nerves.

5.2 Incisors and canines

5.2.1 Anatomical aspects

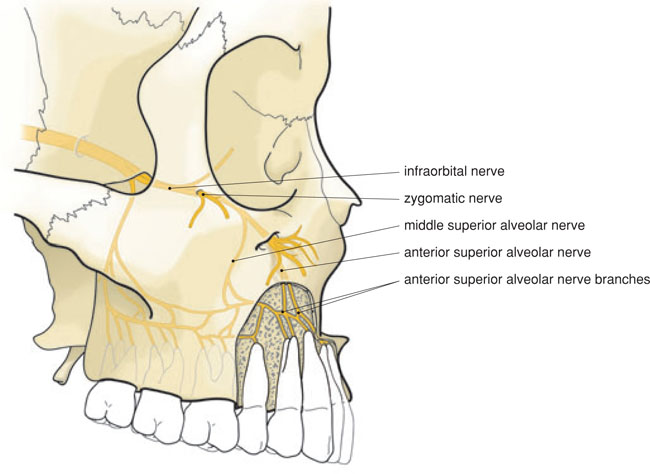

Before leaving the infraorbital foramen the infraorbital nerve branches off in the infraorbital canal towards the incisors and canines, the anterior superior alveolar nerves. These nerve branches provide the sensory innervation of the incisor and canine pulp, as well as the vestibular fold, the gingiva, the periosteum and the bone. They anastomose with small branches of the other vestibular side (Figure 5.2). The nasopalatine nerve leaves the incisive foramen, and provides the sensory innervation of the palatine bone, periosteum and mucosa (Figure 5.3). Because of the relatively thin and porous nature of the maxilla’s cortical bone, an extraperiosteal (infiltration) anaesthetic can spread easily within the maxillary bone.

The apices of the root of the central incisor and canine are found on the buccal side of the bone, whilst the apex of the lateral incisor is found on the palatinal side. This must be taken into consideration when infiltration anaesthetics are given, especially when used for an apicoectomy. The anterior superior alveolar branches run from high lateral to low medial. For this reason, infiltration anaesthetics may best be applied laterally, just above the apex.

5.2.2 Indication

For cavity preparations in the upper frontal teeth, buccal or labial infiltration anaesthesia is usually sufficient. The same applies to endodontic treatments. In cases where a cofferdam is used, or wedges, supplementary palatine anaesthesia is sometimes required. For crown preparations, it is sensible to use buccal and palatine infiltration anaesthesia.

Figure 5.2 Branches of the infraorbital nerve, before and after its exit via the infraorbital foramen.

Figure 5.3 Palatal aspect of the upper jaw with the nasopalatine and greater palatine nerves.

Figure 5.4 A cotton bud, soaked with a topical anaesthetic, in the nose of a patient in order to numb the intraossal branches of the nasopalatine nerve.

For surgical procedures in the upper frontal teeth area, such as periodontal surgery, implants, extractions and apicoectomies, it is advisable to anaesthetise a larger area using regional block anaesthesia with supplementary infiltration anaesthesia. Because regional block anaesthesia is highly effective in this area, it can be directly followed by infiltration anaesthesia. The infraorbital and nasopalatine nerves can be reached via the infraorbital foramen and the nasopalatine canal. Infiltration anaesthesia is given in the buccal area and, if necessary, in the interdental (palatine) papillae. Nevertheless, there are exceptions where good anaesthesia is not achieved. The intraossal branches of the nasopalatine nerve are responsible for this. These smaller branches can be anaesthetised by an injection or the application of a cotton bud with anaesthetic ointment in the respective nostril (Figure 5.4).

5.2.3 Technique

Buccal infiltration anaesthesia of the upper frontal teeth is performed by lifting the lip with the free hand, gently pinching the lip and then piercing the mucosa of the buccal fold with the needle, just above the apex of the respective tooth. The syringe is thereby held parallel to the longitudinal axis of the tooth. The needle is inserted no more than 3–5 mm. Any contact of the needle point with the periosteum or the bone must be avoided, and the fluid must be injected slowly. Aspiration is recommended but not really necessary: there are no large blood vessels in this area (Figure 5.5).

Palatine infiltration anaesthesia is applied in the palatal gingiva of the respective tooth. This anaesthesia is particularly painful if the needle is moved up over the periosteum and when not injected extremely slowly. It is, therefore, sensible to insert the needle tangentially and not to move it up, or to resort to palatine conduction anaesthesia for the central and lateral incisors (Figure 5.6A and B).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses