CHAPTER 5

Erythema

• Contact hypersensitivity reaction

• Acute erythematous candidosis (candidiasis)

• Chronic erythematous candidosis (candidiasis)

• Median rhomboid glossitis (superficial midline glossitis, central papillary atrophy)

• Geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans, stomatitis migrans)

• Folic acid (folate) deficiency

• Infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever)

General approach

• Erythema of the oral mucosa may be due to trauma, infection, immune-related disease, or neoplasia.

• Most erythematous lesions within the mouth will cause a degree of discomfort, although this is not usually severe. Occasionally, erythematous lesions may be painless.

• Some erythematous patches are premalignant and therefore biopsy should be routinely undertaken unless there is no doubt about the diagnosis.

• Erythematous lesions affecting the oral mucosa are usually widespread.

Patterns of erythema are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Patterns of erythema and differential diagnosis

Painful and may ulcerate

• Radiation therapy mucositis

• Contact hypersensitivity reaction

• Erosive lichen planus

Painful with no ulceration

• Acute erythematous candidosis (candidiasis)

• Geographic tongue

• Median rhomboid glossitis

• Angular cheilitis

• Iron deficiency anemia

• Pernicious anemia

• Folate deficiency

Painless with no ulceration

• Erythroplakia

• Chronic erythematous candidosis (candidiasis)

Painless and may ulcerate

• Squamous cell carcinoma

• Infectious mononucleosis

Radiation therapy mucositis

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Ionizing radiation is used to treat many malignancies by targeting dividing cells. For oral SCC, radiation is typically given in 2 Gy daily fractions up to about 70 Gy. The therapeutic effects of radiation are dose dependent, as are the complications. The effect of radiation is nonspecific and therefore normal cells, like malignant ones, undergoing division are also susceptible to the therapy. Basal epithelial cells, which divide frequently, are particularly susceptible to radiation, and this can lead to mucositis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Typically, multiple painful red patches and areas of ulceration develop throughout the oral mucosa (208, 209). Nonkeratinized surfaces, such as the buccal mucosa and the floor of the mouth, are particularly susceptible to radiation damage. Mucositis usually begins 1–2 weeks after the start of radiation therapy. The condition may persist for several weeks after the termination of treatment.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is made on clinical history and examination. Biopsy is not necessary and is generally contraindicated during the radiation treatment.

MANAGEMENT

Keeping the mouth clean is the most important aspect of management. Rinsing the mouth frequently with warm water and baking soda mouthwashes limits the likelihood of infection. Chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.2%) may also be used but a brown coloration often develops on the dorsum of the tongue. The chlorhexidine can be diluted in water up to 10-fold to reduce this problem and the discomfort experienced by some patients. Topical anesthetic agents may be necessary for painful lesions. Alcohol-containing mouthwashes are contraindicated since they cause further atrophy of the mucosa and pain. Investigations should be performed to determine the presence of any secondary candidosis (candidiasis) or staphylococcal infection. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy is required if culture detects infection.

208, 209 Postradiotherapy mucositis.

Lichen planus

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The cause of lichen planus is not known, although it is immunologically mediated and resembles, in many ways, a hypersensitivity reaction to an unknown antigen. T-lymphocyte-mediated destruction of the basal keratinocytes and hyperkeratinization produces the characteristic clinical lesions.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Lichen planus characteristically presents as white patches (Chapter 4, p. 66). However, the atrophic and erosive forms of the disease may produce erythematous lesions with or without white striae (210–214).

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of this form of lichen planus is likely to require a biopsy. Immunofluorescence studies on fresh tissue can be an important aid in establishing the diagnosis.

MANAGEMENT

The first line of treatment in symptomatic cases should consist of a chlorhexidine mouthwash to clean the lesions combined with topical steroid therapy in the form of either betamethasone sodium phosphate (0.5 mg) or prednisolone sodium phosphate (5 mg) dissolved in water and used as a mouthwash for 2 minutes 2–4 times daily. Other preparations of topical steroid therapy, such as sprays, mouthwashes, creams, and ointments, have been found to be beneficial for some patients. Clobetasol is a particularly effective topical agent. A short course of systemic steroid therapy may be required to alleviate acute symptoms in cases involving widespread ulceration, erythema, and pain. Other drugs used in lichen planus include cyclosporine (ciclosporin) mouthwash, topical tacrolimus, and systemic mycophenolate.

The possibility of coexisting oral candidosis (candidiasis) should be investigated and, if present, appropriate systemic antifungal agents prescribed.

210–212 Erythema of the attached gingivae and buccal mucosa in erosive lichen planus.

213 Erythema of the attached gingivae in erosive lichen planus.

214 Erosive and reticular forms of lichen planus affecting the upper and lower gingivae.

Contact hypersensitivity reaction

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

A contact hypersensitivity reaction can be caused by an array of foreign materials, such as toothpastes, mouthwashes, candy, mint, chewing gum, cinnamon, topical antimicrobials, and essential oils. The condition is a cell-mediated immune response requiring antigen presentation by Langerhans cells to T lymphocytes. It is important to note that a suspected reaction to the polymethylmethacrylate material of dentures is rarely a hypersensitivity phenomenon but is more often inflammation as a result of candidal infection.

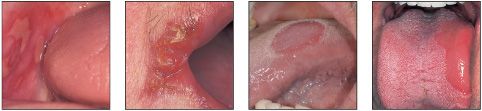

CLINICAL FEATURES

Lesions due to contact allergy usually lie adjacent to the causative agent. Alternatively, reactions to foodstuffs, mouthwashes, or toothpastes may be diffuse (215). The lesions vary from erythematous patches that may show vesiculation to granular red patches.

DIAGNOSIS

History and examination are essential in making a diagnosis. This can be assisted by biopsy, although the histological findings are often nonspecific. Cutaneous patch testing is helpful in diagnosis. Candidal infection can be excluded by the use of a swab, imprint culture, or biopsy of lesional mucosa.

MANAGEMENT

The primary treatment is to eliminate the cause of the allergic reaction and this is usually followed by resolution within a few weeks. Topical corticosteroid treatment can help to reduce the presenting symptoms until the causative factor is corrected. Amalgam restorations can be replaced with composite material and in the rare case of a reaction to a polymethylmethacrylate denture this can be replaced with an appliance made from nylon.

Acute erythematous candidosis (candidiasis)

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

In the past the term ‘atrophic’ has been used to describe this form of candidosis (candidiasis). However, it is now appreciated that the mucosa is not atrophic and therefore the term ‘erythematous’ is preferred. Factors that predispose to erythematous candidosis (candidiasis) include systemic antibiotic therapy, inhaled steroid therapy, and immunosuppression.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Acute erythematous candidosis (candidiasis) is characterized by the development of red areas of oral mucosa. Although any intraoral site may be affected, the midline of the palate (216) and the dorsum of the tongue (217, 218) are most frequently involved. Unlike other forms of oral candidosis (candidiasis), acute erythematous candidosis (candidiasis) is often painful. This form of candidosis (candidiasis) may be an indication of underlying immunosuppression, including HIV infection.

DIAGNOSIS

A smear from the affected site may demonstrate the presence of Candida species. Alternatively, a swab or imprint culture should be taken and sent for culture.

MANAGEMENT

If the patient is receiving antibiotic therapy, consideration should be given to discontinuing this treatment. Patients on steroid inhaler therapy should be advised to rinse or gargle with water after inhaler therapy to minimize the persistence of the drug in the oral cavity. The use of a systemic antifungal, such as fluconazole 50 mg daily for 7 days, should be considered if the patient is otherwise unwell or medically compromised. In the absence of any obvious cause, systemic immunosuppression, including HIV infection, should be suspected.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses