Chapter 5

Dental Amalgam

Aim

Amalgam is one of the most established materials for the restoration of posterior teeth, but recently its use has been challenged because of health and environmental concerns. The aim of this chapter is to increase knowledge of dental amalgam, including its use with enamel and dentine adhesive systems in the bonded amalgam technique.

Outcome

Readers will gain insight into the indications, advantages and disadvantages of amalgam, including its safe use and disposal.

Introduction

In many countries, dental amalgam continues to be one of the most widely used dental materials for the restoration of posterior teeth. It has been successfully used for over 170 years, with favourable cost-effectiveness and clinical durability. Dental amalgam is, however, unaesthetic and lacks the ability to bond to remaining tooth tissues.

Indications

Amalgam is primarily indicated for the restoration of occlusal and occlusoproximal cavities in posterior teeth. It also continues to find application as a core build-up material prior to preparing a tooth for a crown. The use of dental amalgam is falling internationally, with the application of tooth-coloured alternatives increasing steadily.

Advantages

-

cost-effective

-

less technique-sensitive than composite resin

-

high clinical survival rates (durability)

-

fewer allergic or hypersensitivity reactions than composite resin

-

strong evidence base.

Disadvantages

-

unsightly restorations

-

does not bond to tooth substance, requires mechanical retention and resistance features

-

relatively low tensile strength, weak in thin (<2 mm) sections

-

few, if any, applications in minimally interventive dentistry

-

concerns regarding mercury as a potential toxin and environmental contaminant.

Composition

Dental amalgam is created when mercury is mixed, or triturated, with metal alloys. The composition of the metal alloys used has changed with time. Zinc-free and, in particular, high-copper alloys now predominate. The compositions of conventional (low-copper) and high-copper amalgam alloys are given in Table 5-1. In addition to the major elements, alloys may also contain small amounts of palladium, platinum, indium and gold.

| Component | Conventional amalgam (% by weight) | High-copper amalgam (% by weight) |

| Silver | 63–70 | 40–70 |

| Tin | 26–28 | 22–30 |

| Copper | 2–5 | 13–40 |

| Zinc | 0–2 | 0–2 |

Modern dental amalgam alloys may be classified as admixed high-copper alloys or single-composition high-copper alloys. As the alloy composition varies, so does the setting reaction. The metal alloy powder is triturated with liquid mercury in a sealed plastic capsule (Fig 5-1) using a mechanical triturator or amalgamator (Fig 5-2).

Fig 5-1 Example of amalgam capsules which contain prepro-portioned mercury liquid and amalgam alloy powder, together with a small plastic pestle that mixes the components together when the capsule is mechanically mixed in an amalgamator. Also shown are a dappen dish, used to hold the triturated amalgam, and a plastic amalgam carrier, used to syringe the mixed amalgam into a prepared cavity.

Fig 5-2 Example of a dental amalgamator, used to mechanically mix amalgam capsules containing preproportioned mercury liquid and amalgam alloy powder. Note the clear plastic lid, which should be closed during mixing to minimise any release of mercury vapour.

The mixing process produces a soft silver pellet of dental amalgam, which is condensed in increments into the cavity using a hand-held amalgam condenser. For condensation of the amalgam to be effective, amalgam condensers must be firmly applied to adapt the material and remove excess mercury. Given the need to firmly condense amalgam, matrices must be secure and well wedged if marginal excesses are to be avoided.

When triturated, mercury dissolves silver and tin from the metal alloy particles to form matrices of intermetallic compounds that bind the silver–tin particles (gamma phase) together into a solid set mass. The details of the setting reaction vary with the type of alloy used.

Amalgam Trituration

-

Overtrituration produces a hot, sticky mix with decreased working and setting time and slightly increased setting contraction.

-

Undertrituration produces a grainy, crumbly mix, which cannot be used.

Conventional (Low-copper) Alloys

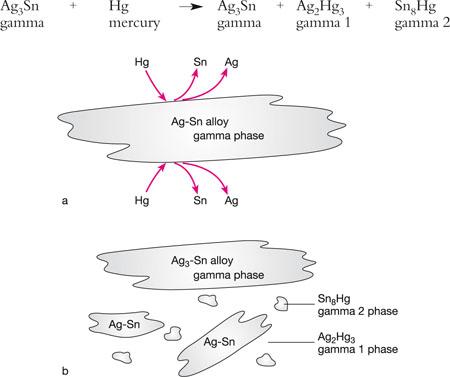

On trituration, a conventional (low-copper) alloy with a silver–tin alloy (gamma phase) releases tin and silver, which react with mercury to form silver–mercury (gamma 1) and tin–mercury (gamma 2) phases (Figs 5-3a and 5-3b).

Fig 5-3 (a) The interaction between mercury and a conventional (low-copper) amalgam alloy. The outer aspects of the silver–tin alloy particles (gamma phase) dissolve in the mercury, releasing tin and silver. (b) The compounds formed by the release of silver and tin, primarily gamma 1 phase (Ag2Hg3) and gamma 2 phase (Sn8Hg). The final structure of a set, low-copper amalgam consists of large amounts of unreacted gamma phase (Ag3-Sn), together with smaller amounts of gamma 1 and gamma 2 phases.

Admixed High-copper Alloys

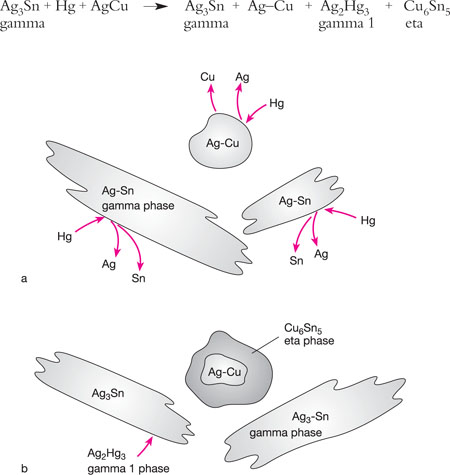

When triturated, tin moves to the surface of the silver–copper alloy particles and reacts with the higher copper content to create a new copper–tin (eta phase), which surrounds the unreacted cores of the silver–copper particles. These particles are bound together with silver–mercury (gamma 1) phase (Figs 5-4a and 5-4b). Thus, there is almost no gamma 2 phase in these amalgams, which is weak and susceptible to corrosion.

Fig 5-4 (a) The interaction between mercury and an admixed high-copper amalgam alloy. The mercury diffuses into the silver–copper particles, releasing silver and copper, while the silver-tin alloy particles (gamma phase) release silver and tin. (b) The mercury reacts with the silver–tin particles and forms gamma 1 (Ag2Hg3) and gamma 2 (Sn8Hg) phases, as for a low-copper alloy, leaving some gamma phase (Ag3Sn) unreacted. The newly formed gamma 2 phase reacts with the silver–copper particles to form Cu6Sn5 (eta phase). These reactions almost totally eliminate the gamma 2 phase, which is responsible for susceptibility to corrosion.

The actions of each amalgam alloy constituent are summarised in Table 5-2.

| Constituent | Actions |

| Silver | Increases strength and expansion |

| Tin | Increases setting time, decreases strength and expansion |

| Copper | Increases strength, reduces corrosion, reduces creep, reduces amount of weak gamma 2 phase |

| Zinc | Used in manufacturing to reduce oxidation of other elements; may cause delayed expansion if contaminated with water |

| Indium | Decreases creep, increases strength, decreases surface tension and therefore reduces amount of mercury required |

| Palladium | Reduces corrosion |

High-copper Alloys

High-copper alloys are now the most popular type of amalgam used, as they give high />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses