43 Perforations

A root perforation is a mechanical or pathologic communication formed between the supporting periodontal apparatus of the tooth and the root canal system (AAE glossary, 2003). Perforations occur as a complication of endodontic treatment and restorative procedures such as post preparation; the reported rate ranges from 1% to 3% (Kerekes and Trondstad, 1979; Eleftheriadis and Lambrianidis, 2005; Jamani and Fayyad, 2005). In addition to iatrogenic perforations, pathologic processes such as tooth resorption or caries may also result in root perforation.

Kvinnsland et al. (1989) evaluated the etiology and location of 55 root perforations seen in a dental school in Norway. Almost 50% of the perforations were due to endodontic treatment and slightly more than 50% were due to prosthodontic treatment. The buccal and mesial root surfaces, as well as the midroot areas, were most often perforated.

According to Fuss and Trope (1996), the important factors in determining the success of a perforation repair are the time interval between the occurrence of a perforation and its repair, the size of the perforation, and its location. The authors presented a classification of root perforations based on the above factors.

The location of the perforation in relation to the level of the epithelial attachment and crestal bone is probably the most important factor in terms of prognosis. The closer the perforation is to this critical zone, the poorer the prognosis, due to susceptibility of the site of perforation to contamination from microorganisms from the oral cavity. Moreover, if the perforation is not closed immediately, apical migration of the epithelial attachment may occur, resulting in a periodontal defect. Fuss and Trope (1996) concluded that successful treatment depends mainly on immediate sealing of the perforation and prevention of infection.

Classification of Root Perforations

|

Good prognosis |

Poor prognosis |

|

– Fresh |

– Old |

|

– Small |

– Large |

|

– Apical-coronal |

– High alveolar ridge |

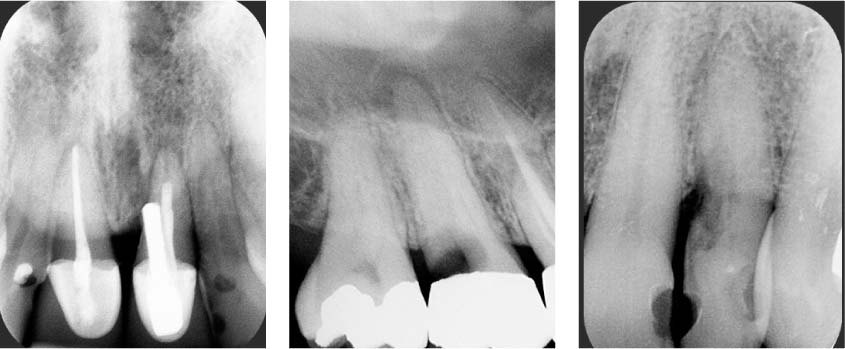

43.1 Perforations caused by a procedural error, caries, or a resorption process

Left: Radiograph showing a crestal perforation, due to a misaligned post placement.

Middle: Radiograph showing deep caries resulting in perforation.

Right: Radiograph showing cervical invasive resorption resulting in perforation.

Diagnosis of Perforation

As the time interval between the occurrence of the perforation and its repair is an important prognostic factor for treatment outcome, early determination of the occurrence of a perforation is of paramount importance. A diagnosis is established based on clinical and radiographic findings. Radiographs from different angles, including bitewing radiographs, are indispensable for an accurate diagnosis. In addition, the presence of a sinus tract or the appearance of localized problems such as pocket formation or furcation involvement may indicate the existence of perforation (Aldahainy, 1994).

During treatment perforations can be identified by direct observation through the microscope, direct observation of bleeding at an unanticipated location, indirect bleeding assessment using a paper point, and the use of an apex locator. Moreover, reports of sudden and unprovoked pain may indicate that the file is penetrating the surrounding bone.

Management of perforations will depend on a number of factors, including the size and location of the perforation and access to the perforation site. Subgingival perforations can usually be repaired with materials such as amalgam, composite or cast metal restorations, by extending the cervical margin to include the defect.

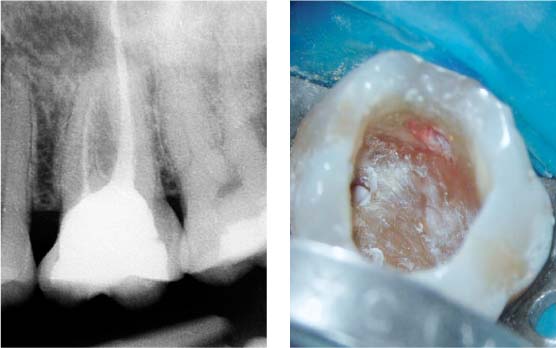

43.2 Subgingival perforation

Left: Radiograph showing a maxillary first molar with a large restoration and an insufficient root canal filling in the mesial root. Because a crown has been planned on tooth 26, retreatment is appropriate. Localized gingivitis is present between teeth 25 and 26, and a perforation is suspected on the mesial aspect of tooth 26, because of the close proximity of the restoration to the interdental papilla.

Right: After removing the composite restoration, a subgingival perforation became visible.

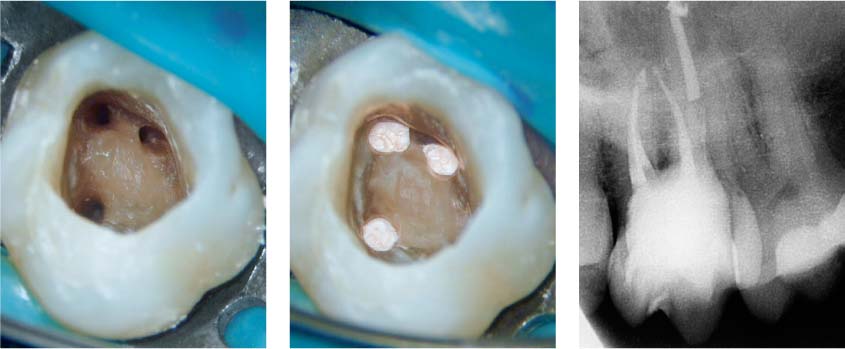

43.3 composite Perforation sealed with

Left: Prior to initiating the root canal treatment, the perforation has been sealed with a composite restoration. A second mesiobuccal canal has been detected and instrumented.

Middle: Four canals have been obturated.

Right: A fiber post has been placed in the palatal canal, and a build-up of composite core material has been constructed.

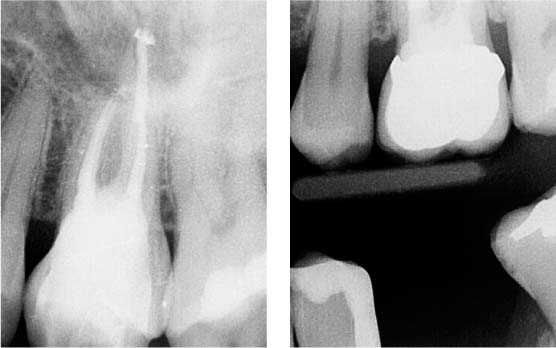

43.4 Follow-up

Left: Postoperative radiograph.

Right: At 6-month follow-up, a crown has been placed that encompasses the defect; the gingiva is free of inflammation and the patient is symptom-free.

Management of Perforations

The primary goal in management of perforations is to arrest the inflammatory process and the subsequent loss of tissue attachment by preserving healthy tissues at the site of the perforation. Many materials have been used to repair perforations, including: amalgam, Cavit (3M-ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA), calcium hydroxide, super-EBA, glass ionomer, composite, gutta-percha, and zinc oxide eugenol cement. The success rate of these materials has been variable.

Since the introduction of MTA, substantial evidence has collected that it is the material of choice for perforation repair (Lee et al., 1993; Pitt Ford et al., 1995). It is biocompatible, provides a tight seal, and promotes the regeneration of cementum, thus facilitating the regeneration of the periodontal tissues. This characteristic differentiates MTA from other comparable materials.

Main et al. (2004) presented a series of cases that demonstrated consistent healing with the use of MTA as a perforation re/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses