41 Traumatology

Epidemiologic studies have shown that one in two children experiences dental trauma, usually between the ages of 8 and 12. For a determination of the extent of the injury, as well as for planning appropriate therapy, a complete diagnostic examination is critical. The initial clinical examination must include determination of tooth mobility and displacement, careful periodontal probing, assessment of soft-tissue injury, as well as percussion and sensitivity tests. Radiographic examination is essential.

As trauma often leads to multiple injuries, less obvious injuries on the tooth in question and the adjacent teeth or antagonists should not be overlooked. Also, for forensic reasons, it is necessary to examine the alveolar processes, the mandible, and mid-face for signs of possible fracture and other serious injuries in the head/neck region.

Complete and clearly documented clinical findings will help to reach an accurate diagnosis and determine any subsequent necessary treatment.

The consequences of dental trauma are many, presenting as injury to various structures of the teeth or surrounding tissues. Especially in complex cases, restorative, endodontic, and periodontal aspects must be all be taken into consideration during treatment planning. In addition, since mainly children and young adults are affected by dental trauma, treatment must avoid negative effects on further jaw growth and take into consideration the life expectancy of the patient.

Emergency treatment often includes simple measures such as splinting in cases of dislocation, or covering exposed dentin in cases of crown fracture (Andreasen et al., 2007).

However, even the best treatment cannot completely rule out the possibility of late sequelae of trauma, and a regular follow-up regimen will ensure timely detection and treatment.

The prognosis in cases of dental trauma depends on a myriad of factors. The prognosis is often favorable if adequate therapeutic intervention is performed in time. Establishing the prognosis is more difficult if treatment is delayed or not carried out properly. In most trauma cases involving children and young adults, the main objective is the retention of the affected tooth until the patient is of an age when a dental implant would be feasible.

In cases of severely compromised teeth, consideration should be given as to whether it will be prudent to attempt to preserve a tooth with a questionable prognosis, or whether alternative treatment methods are more suitable. Thus in the case of young patients, orthodontic treatment should not be disregarded, and collaboration with an orthodontist is recommended. In some cases, tooth transplantation offers an alternative biologic approach to replacement of untreatable traumatized teeth (Lang et al., 2003).

Classification

According to the most current World Health Organization classification (WHO 2006), dental traumas are classified as fractures and dislocation injuries. The much-used term “luxation injury” implies the presence of a joint, and is therefore not accurate. Fractures are classified according to their localization, whereas dislocation injuries are classified according to the extent and direction of the trauma-induced dislocation of the tooth from its original position in the dental arch.

The maxillary central incisors are the teeth most often affected by dental trauma within the permanent dentition (ca. 60%), followed by the maxillary lateral incisors (ca. 22%). Mandibular anterior teeth are relatively seldom involved (central incisors 7.7%, lateral incisors 4.6%) (Borum and Andreasen, 2001).

Whereas in the permanent dentition, tooth fractures are the predominant result of trauma, in the primary dentition, because of the more elastic structure of the alveolar process in young children, dislocation injuries are more frequently observed (Schatz and Joho, 1994).

|

Fracture |

Clinical finding |

|

Enamel crack infraction |

Visible crack in the enamel without substance loss |

|

Crown fracture (with or without pulpal involvement) |

Enamel or enamel-dentin fracture with possible pulp exposure |

|

Crown/root fracture (with and without pulp exposure) |

Mobile crown fragment, often attached to the gingiva Not always with pulpal involvement |

|

Transverse root fracture |

Horizontal or oblique fracture of the root Increased mobility of the crown fragments, possibly with dislocation Depending on the location of the fracture line, communication with the oral cavity is possible via the gingival sulcus |

|

Dislocation |

Findings |

|

Concussion |

Sensitive to touch No increased mobility |

|

Mobility |

Sensitive to touch Increased mobility Possible hemorrhage from the gingival sulcus |

|

Lateral dislocation |

Dislocation usually in the lingual direction Often tooth wedged in this position, without sensitivity to percussion and a metallic percussion sound |

|

Extrusion |

Tooth appears elongated with increased mobility |

|

Intrusion |

Tooth appears shortened Metallic percussion sound due to wedging within the alveolar bone |

|

Avulsion |

Complete luxation of the tooth from its socket |

Frequently occurring findings in various types of injury.

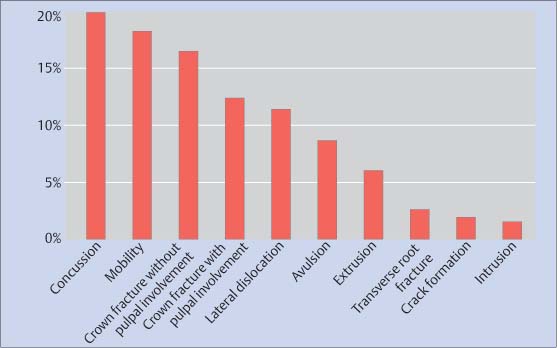

41.2 Frequency of traumatic dental injuries

Frequency of various types of dental trauma in the permanent dentition (Borum and Andreasen, 2001).

Crown Fractures without Pulpal Involvement

Most crown fractures result in dentin exposure. In order to avoid the high risk of infection of the endodontic system via the open dentinal tubules, all emergency treatment must include coverage of exposed dentin (Andreasen et al., 2007). Ideally a flowable composite should be bonded to the dentin surface. A definitive, and possibly time-consuming, restoration can be carried out at a later date. To restore function and esthetics, it may be possible to reattach the fractured tooth fragment using an adhesive. The long-term success rate of reattached fractured tooth fragments, as reported in the literature, is 25% at 7.5 years (Andreasen et al., 1995). Extension of the adhesive surface through preparations such as enamel beveling will improve the adhesion (Reis et al., 2001).

A tooth fragment that has been left to dry for an extended period will become dehydrated, which can compromise the esthetic results and bond strength. When the trauma involves multiple or missing tooth fragments, or if these are difficult or impossible to reattach, current composite resin restorative materials provide excellent possibilities for immediate restorative treatment. Indirect ceramic restorations are more invasive and should be restricted to adult patients.

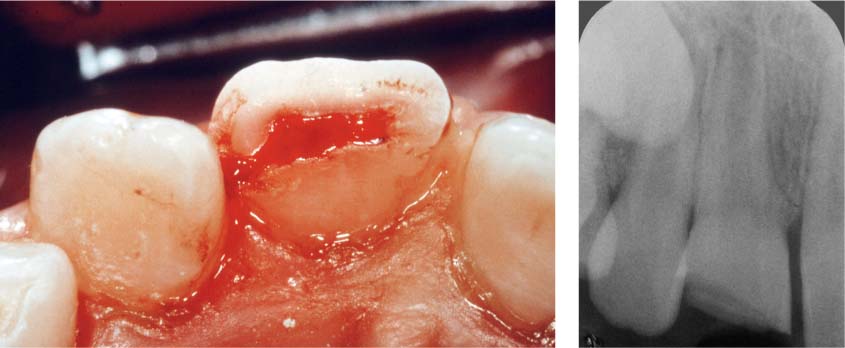

41.3 Enamel-dentin fractures

Left: As part of the primary treatment the previous day, the exposed dentin in teeth 11 and 21 was treated with a calcium-hydroxide cement.

Right: To facilitate manipulation, the tooth fragments were bonded to microbrushes before application of phosphoric acid and dentin adhesive.

41.4 Reattachment—restoration

Left: Following removal of rubber dam, the transition between the freshly attached incisal fragments and the rest of the crown is clearly visible.

Right: The clinical situation 2 years later reveals a satisfactory esthetic result. Both teeth remain vital.

41.5 Composite restoration

Left: Composite restoration was carried out under rubber dam.

Right: Four years following successful treatment, the esthetic clinical situation is unremarkable. Both central incisors continue to react positively to a sensibility test.

Crown Fracture with Pulpal Involvement

Despite traumatic pulp exposure, the prognosis for maintaining tooth vitality in young individuals with crown fractures with pulpal involvement is generally favorable. Treatment of the traumatically exposed pulp depends on the amount of time that has elapsed since the injury. If this occurs within the first 2 hours, direct pulp capping is possible.

Calcium hydroxide has a proven record as a pulp capping material. When applied to an open, vital pulp, calcium hydroxide elicits the formation of new hard tissue in the area of the perforation. An alternative is mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), which is preferable from a biologic point of view although tooth discoloration can impair the esthetic result.

Especially when primary treatment is delayed, 1–2 mm of the (potentially infected) pulp should be removed (partial pulpotomy, Cvek, 1978) before capping. The literature reports higher success rates using this method compared to direct pulp capping independent of the size of the pulpal exposure and the status of root growth. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that pulpal tissue that has been exposed for more than 24 hours to the oral milieu is bacterially infected only in the most coronal region (Cvek, 1982).

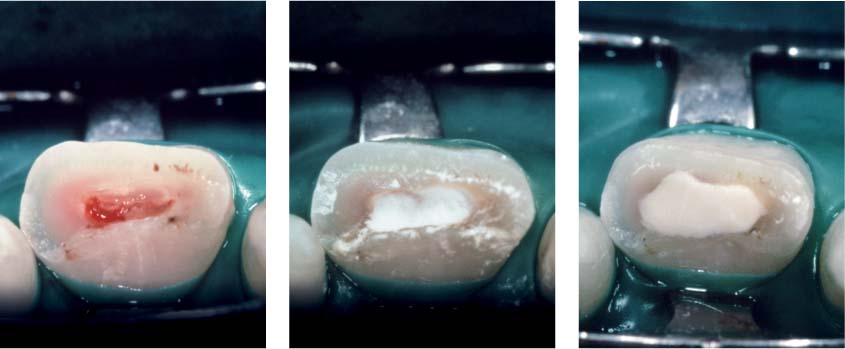

41.6 Crown fracture with a wide pulp exposure

A partial pulpotomy is indicated to maintain tooth vitality.

Right: The radiograph reveals incomplete root development of the fractured tooth. The treatment of choice has as its goal continued root development.

41.7 Partial pulpotomy

Left: Partial amputation of the coronal pulp is carried out using a high-speed diamond bur and cooling with sterile saline solution. Any bleeding should cease within 5 minutes. The lack of continued hemorrhage is evidence that the pulpal tissues are not inflamed, thus confirming the indication for the treatment.

Middle: The artificial wound surface is covered with a calcium-hydroxide preparation.

Right: Covering with a calcium-hydroxide cement.

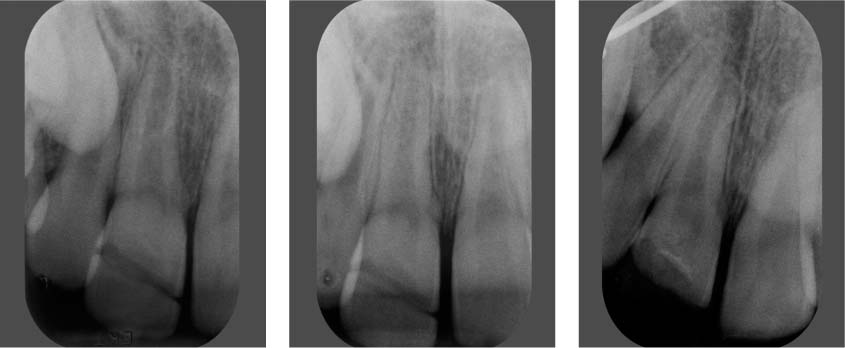

41.8 Radiographic follow-up

Left: At the 6-month recall, the radiograph clearly exhibits the demarcation between the tooth crown and the attached fragments. The fragments were attached using a nonradiopaque composite material.

Middle: The 1-yea/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses