CHAPTER 4

White patches

• Pseudomembranous candidosis (thrush, candidiasis)

• Chronic hyperplastic candidosis (candidal leukoplakia)

• Nicotinic stomatitis (smoker’s keratosis)

General approach

• White patches may develop within the oral mucosa due to trauma, infection, immune-related disease or neoplasia.

• White patches are usually painless, although discomfort can occur due to erosion or ulceration, particularly in lichen planus.

• Some white patches are premalignant and therefore biopsy should be routinely undertaken, unless there is no doubt of an alternative diagnosis.

• White patches may be localized or widespread throughout the mouth. Localized white patches suggest a traumatic or neoplastic etiology, while widespread involvement suggests a systemic, immunological, or hereditary condition.

White patches may be divided into those that are painless and those that may be painful (Table 3).

Table 3 Patterns of white patches and differential diagnosis

White patches often associated with pain

• Lichen planus

• Lichenoid reaction

• Lupus erythematosus

• Chemical burn

White patches rarely associated with pain

• Pseudomembranous candidosis (candidiasis)

• Chronic hyperplastic candidosis (candidiasis)

• White sponge nevus

• Dyskeratosis congenita

• Frictional keratosis

• Leukoplakia

• Nicotinic stomatitis (smokers keratosis)

• Squamous cell carcinoma

• Skin graft

• Hairy leukoplakia

• Pyostomatitis vegetans

• Submucous fibrosis

• Cartilagenous choristoma

Lichen planus

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Lichen planus is one of the more frequently occurring mucocutaneous disorders. The cause of lichen planus is not known, although it is immunologically mediated and resembles, in many ways, a hypersensitivity reaction. T-lymphocyte-mediated destruction of basal keratincytes and hyperkeratinization produces the characteristic clinical lesions.

CLINICAL FEATURES

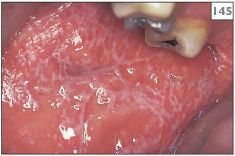

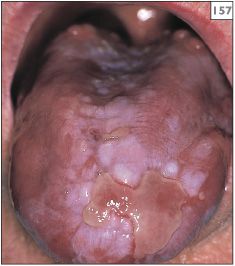

Lichen planus presents as white patches or striae that may affect any oral site, typically with a symmetrical and bilateral distribution. Clinical appearance is variable and at least six forms have been described: reticular (143–148); papular; plaque-like (149); atrophic (150, 151); erosive (152, 153); and (rare) bullous. However, clear division among the different types is often difficult and examination of the mucosa of an individual patient may reveal that more than one subtype is present. In addition, the clinical signs and symptoms may change over a period of time (154–157).

143, 144 Symmetrical reticular lichen planus in both buccal mucosae.

145, 146 Bilateral and symmetrical reticular lichen planus.

147, 148 Reticular lichen planus in the right (147) and left (148) buccal mucosa of the same patient.

149 Plaque-like lichen planus on the dorsum of the tongue.

150 Atrophic lichen planus on the dorsum of the tongue.

151 Atrophic lichen planus on the gingivae.

The cutaneous lesions of lichen planus present as purple, pruritic papules that may develop at any site but most frequently occur on the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs (158). Fine white lines, known as Wickham’s striae, may be seen on the surface of these papules. In contrast to the oral lesions, which may be present for many years, skin involvement usually resolves within about 18 months.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical diagnosis of oral lichen planus is aided by the presence of cutaneous lesions. A mucosal biopsy will show a hyperkeratinized epithelium, basal cell destruction, and a dense band-like infiltrate of T lymphocytes in the superficial connective tissue. Direct immunofluorescence studies are usually helpful to establish the diagnosis, but they must be performed on a fresh tissue biopsy of lesional tissue submitted to the laboratory in a preservative solution, such as Michel’s medium. Characteristically, lichen planus shows a linear deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane but no deposition of Igs or complement.

MANAGEMENT

The patient should be reassured of the benign nature of lichen planus. However, pre-existing lichen planus has occasionally been associated with the development of oral cancer, particularly if known risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol abuse, are present. It is advisable to maintain regular reviews of such patients and a biopsy should be performed if there is a change in clinical appearance.

The first line of treatment in symptomatic cases should consist of an antiseptic mouthwash combined with topical steroid therapy in the form of either prednisolone (5 mg) or betamethasone sodium phosphate (0.5 mg) allowed to dissolve on the affected area 2–4 times daily. Other preparations of topical steroid therapy, such as fluticasone spray (two puffs twice daily) or clobetasol 0.05% as a cream or ointment applied twice daily, have been found to be beneficial for some patients. Intralesional injections of triamcinolone have also been tried with variable success. A short course of systemic steroid therapy may be required to alleviate acute symptoms in cases involving widespread ulceration, erythema, and pain. Other drugs used in lichen planus include cyclosporine (ciclosporin) mouthwash, topical tacrolimus ointment, and systemic mycophenolate.

152 Erosive lichen planus on the buccal mucosa.

153 Erosive lichen planus on the gingivae.

The possibility of coexisting oral candidosis (candidiasis) should be investigated and, if present, appropriate topical or systemic antifungal agents prescribed. Furthermore, stress may be a precipitating factor, especially in older patients, and therefore anxiolytic therapy, such as a tricyclic antidepressant, may be helpful in selected situations.

154–157 Chronological change in the appearance of the tongue over a 4-year period in a patient with lichen planus.

158 Cutaneous lesions of lichen planus on the flexor surface of the wrists.

Lichenoid reaction

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Lichenoid reactions are so named because of the similarity, both clinically and histologically, to lichen planus. Many systemic drugs, especially antihypertensives, hypoglycemics, and NSAIDs, have been implicated in lichenoid reactions. In addition, direct contact with dental restorative materials has been shown to produce localized lichenoid lesions.

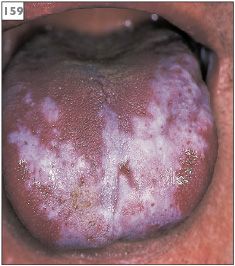

CLINICAL FEATURES

Lesions can occur at any intraoral site, but in contrast to lichen planus it has been suggested that with lichenoid reactions the lesions tend to be solitary or asymmetrical in distribution and may involve the palate, a site not typically associated with lichen planus (159, 160).

DIAGNOSIS

If oral lesions develop within a few weeks of the institution of drug therapy, there is likely to be a connection. Alternatively, if the distribution of lesions matches the position of old amalgams, a hypersensitivity to amalgam should be considered (161, 162). More recently, lichenoid reactions to composite materials have been reported. Mucosal biopsy is often helpful in supporting the diagnosis of a lichenoid reaction, although the changes may be difficult to differentiate from lichen planus or may be nonspecific. Direct immunofluorescence studies do not reliably differentiate hypersensitivity and lichen planus.

MANAGEMENT

If the patient is taking a medicine known to be associated with the occurrence of lichenoid lesions, consideration should be given to a change of therapy to a structurally unrelated drug with similar therapeutic effect. In the absence of obvious precipitating factors, cutaneous patch testing may be helpful in identifying potential allergens, which can then be excluded. In the case of a reaction to amalgam, patch testing often detects a hypersensitivity to mercury and ammoniated mercury. Replacement of the amalgam restorations with alternative materials will result in the resolution of mucosal lesions within a few weeks. In the short term, topical anti-inflammatory agents or steroids can relieve symptoms.

159 Lichenoid drug reaction with asymmetric distribution on the tongue.

160 Lichenoid drug reaction with asymmetric distribution on the buccal mucosa.

161 Lichenoid drug reaction on the buccal mucosa related to hypersensitivity to amalgam.

162 Lichenoid reaction in the right buccal mucosa related to amalgam restoration in the lower molar tooth.

Lupus erythematosus

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by the production of antinuclear autoantibodies. Immune complexes (type III hypersensitivity) are formed and deposited along the basement membrane, leading to basal cell damage. In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) there is multisystem organ involvement resulting in kidney, pulmonary, cardiac, and joint disease. In discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) the disease is confined to the skin, but oral lesions develop in 15% of sufferers.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients with DLE have discrete, raised, erythematous, scaly patches and plaques on sun-exposed skin that progress to atrophic hypopigmented scars. The oral lesions of lupus erythematosus consist of localized striated, keratotic, and erythematous patches that resemble lichen planus (163). The most striking sign of SLE is a butterfly rash on the skin of the malar processes. Many patients with SLE also suffer from xerostomia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca and form a component of secondary Sjögren’s syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Serological evidence of autoantibodies is important for the diagnosis of SLE. Several methods are used but the most frequent is by indirect immunofluorescence. Histological examination of the oral mucosa shows basal cell destruction, basement membrane thickening, and lymphocytic infiltrates in the superficial connective tissues and in a perivascular distribution. Direct immunofluorescence examination shows granular immune deposits, typically IgG and IgM, along the basement membrane (lupus band test).

MANAGEMENT

SLE is managed systemically using immunosuppressive agents. Symptomatic intraoral DLE can be managed in a similar manner to oral lichen planus. Specifically, the first line of treatment should consist of an antiseptic mouthwash combined with topical steroid therapy in the form of betamethasone sodium phosphate (0.5 mg) allowed to dissolve on the affected area 2–4 times daily. Other formats of topical steroid therapy, such as sprays, mouthwashes, creams, and ointments, have been found to be beneficial for some patients. Intralesional injections of triamcinolone have also been tried, with variable success. The antimalarial drugs hydroxy chloroquine and dapsone have also been used successfully to manage oral DLE. In severe cases, characterized by widespread ulceration, erythema, and pain, a short course of systemic steroid therapy may be required to alleviate acute symptoms.

163 Radiating white patches with erythema in the buccal sulcus, which is characteristic of the oral lesions of lupus erythematosus.

Chemical burn

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The topical application of any caustic chemical to the oral mucosa can result in a superficial chemical injury. A classical example of a chemical burn is that due to aspirin. Some patients attempt to treat an area of oral discomfort or toothache by the application of aspirin directly to the affected site. Patients may also place preparations based on aspirin on the fitting surface of dentures in order to relieve discomfort. The low pH of aspirin causes erythema and tissue necrosis and, with increasing contact time, coagulative necrosis. Eventually there is the formation of a white slough on the surface.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Chemical burns appear as a white, friable slough that can be easily removed, leaving a bed of erythema and ulceration. The most frequently involved site is the buccal sulcus or alveolar attached gingivae (164). Alternatively, chemical burns may be seen under a full denture.

DIAGNOSIS

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses