Chapter 4

Techniques for Maxillary Anaesthesia

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe the different methods available to anaesthetise the upper teeth and their associated structures.

Outcome

After reading this chapter you should have an understanding of the different local anaesthetic techniques used in the upper jaw. You will understand the indications for use of each method.

Introduction and Terminology

The maxillary teeth may be anaesthetised by infiltration, regional block, intraligamentary, intra-osseous and intrapulpal anaesthesia. The primary method is infiltration anaesthesia. This chapter will describe the infiltration and regional block methods used in the upper jaw.

As a general rule for all injections in both jaws the patient position should be such that it allows access to the point of injection while affording the safest and most comfortable placement for the patient. Ideally the patient should be fully supine to aid cranial blood flow and prevent fainting. Some patients may be uncomfortable or feel vulnerable in this position. A compromise is to tilt the chair back at least thirty degrees to the vertical.

Buccal Infiltration Anaesthesia

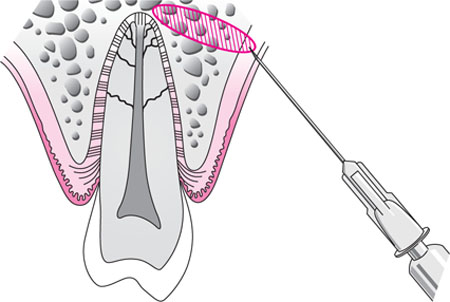

Solution deposited at the buccal side of the maxillary alveolus can infiltrate through to the pulps of the teeth to produce dental anaesthesia (Fig 4-1). This is because the cortical plate on the buccal side of the maxilla is thin. The advantages of infiltration anaesthesia are:

-

simple technique which is easy to master

-

when successful, anaesthetises all nerve endings in the area of deposition independent of the nerve source.

Fig 4-1 Infiltration anaesthesia is achieved when solution is deposited supraperiosteally at the buccal side of the alveolus.

The disadvantages are:

-

only effective in obtaining pulpal anaesthesia when diffusion through cortical bone occurs

-

localised infection may be spread if an inflamed area is infiltrated

-

only a limited zone of anaesthesia per injection.

Technique

The syringe is fitted with a 27 or 30 gauge needle. Usually a 20–25 mm-long needle is employed. Unless there is a medical contraindication a vasoconstrictor-containing anaesthetic such as lidocaine with epinephrine is used.

The point of needle penetration is in the buccal fold within reflected mucosa (Fig 4-2). Access to this region is easiest when the patient has the mouth only partly open. This is especially the case in the more posterior regions of the buccal sulcus. When the mouth is fully open the buccal tissues are stretched across the teeth, limiting access. Prior to injection this area should be cleaned with a gauze swab and a topical anaesthetic applied. The operator pulls the cheek or lip in a superior direction to stretch the tissues and the needle is inserted through the taut tissues of the buccal fold. This stretching of the lip or cheek may be performed by holding the tissues between the operator’s fingers (Fig 4-2) or by retraction with a mirror (Fig 4-3). The former method affords more control; the latter reduces the chances of needle-stick injury. The choice is personal. It is important to stretch the tissue at the puncture-point. This enables smooth needle penetration with minimal dragging of the mucosa. The needle must be inserted into a plane deeper than the epithelium. Injecting into the epithelium produces a distinct blister. This produces discomfort and, if noted, the needle is advanced to a deeper level. The needle is directed towards the bone, aiming for the apical area of the tooth in question (Fig 4-4). Bone does not need to be contacted. If bone is touched the needle should be withdrawn slightly so that the point is not subperiosteal. An injection underneath the periosteum is painful at the time and in the postanaesthetic stage. Before injecting, aspiration is performed. The incidence of positive aspiration during buccal anaesthesia is low (around 1–2%). If aspiration is negative then 1 mL of solution is deposited over a period of 30 seconds. At least two minutes should elapse before testing for the effect of the anaesthetic.

Fig 4-2 A maxillary buccal infiltration injection; access is achieved by pulling on the lip with the fingers.

Fig 4-3 In this delivery of an infiltration injection, the lips are retracted by a dental mirror. This reduces the chances of a needlestick injury during the injection.

Fig 4-4 The position of the needle for an infiltration in the upper canine region.

This technique will normally anaesthetise the pulps of the tooth in question and the contiguous teeth. The soft tissues on the buccal side, including the periodontal ligament and the buccal alveolar bone in the region, will also be anaesthetised.

Pulpal anaesthesia of around 45 minutes should ensue when a vasoconstrictor-containing solution has been used. The efficacy of infiltration anaesthesia is dependent upon the volume and concentration of the local anaesthetic solution and the presence of a vasoconstrictor. The efficacy of lidocaine as an anaesthetic during infiltration anaesthesia increases with increasing epinephrine concentration. Long-lasting local anaesthetics do not provide prolonged postoperative pain relief if injected by infiltration although soft tissue anaesthesia is prolonged.

Problems with buccal infiltration anaesthesia

Buccal infiltrations may fail if there is collateral supply to the pulp from the greater palatine or nasopalatine nerves. This is overcome by supplementing the injection with one of the palatal techniques described below.

Another reason for failure may be due to a thick cortical plate reducing the spread of solution through bone. This may occur in the region of the zygomatic buttress causing failure of anaesthesia in upper first molars. This is overcome by infiltrating mesially and distally to the buttress or by using the regional block methods described below. It must be remembered that the upper first molar tooth can receive supply from both the posterior and the middle superior alveolar nerves, thus two blocks may be required in some cases.

If there is localised infection at the site of an infiltration it is unwise to inject at this zone. Using one of the regional block methods described below surmounts this problem.

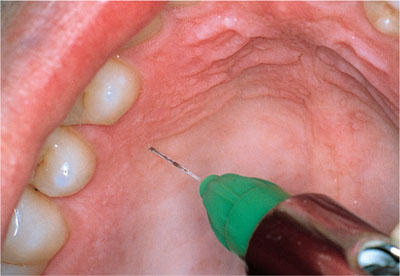

Palatal Infiltration

When working on the tissues distal to the canine the palatal soft tissue can be anaesthetised by infiltration (Fig 4-5) or regional block anaesthesia (see below). Infiltration of around 0.2 mL of solution into the palatal mucosa just distal to the tooth of interest will anaesthetise the palatal mucosa and periodontium anterior to the point of infiltration up to the canine region. The exception is the upper third molar when the solution should be deposited at the anterior aspect of the tooth. This is because the greater palatine foramen lies anterior to the third molar tooth (Fig 4-6) and the nerve supplying this region travels in a posterior direction. The point of infiltration is in the fleshiest part of the palate around 10 to 15 mm from the gingival margin (Fig 4-5). The duration of infiltration and greater palatine nerve block anaesthesia in the palate is similar. Thus the choice of technique in the posterior part of the palate is personal. In the anterior region a nasopalatine block is the preferred method.

Fig 4-5 A palatal infiltration injection.

Fig 4-6 The position of the greater palatine foramen. It is anterior to the third molar.

Palatal injections can be uncomfortable owing to the poor compliance of the tissue. Chapter 9 describes methods of reducing this discomfort by chasing local anaesthetic solution through from already anaesthetised buccal papillae.

Regional block methods in the maxilla

Regional block anaesthesia may be used in the maxilla if infiltration methods are ineffective or to avoid multiple injections when a large area of anaesthesia is needed. Only intraoral approaches will be described. It is possible to approach the maxillary nerve and some of its branches from extraoral approaches but these are not recommended in dental practice.

Regional block methods useful in the maxilla include:

-

posterior superior alveolar nerve block

-

maxillary molar nerve bl/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses