Chapter 6

Supplementary Techniques

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to describe methods of anaesthesia other than infiltration and regional block methods that are used in dentistry.

Outcome

After reading this chapter you should have an understanding of the usefulness and indications for supplementary anaesthetic techniques in the mouth.

Introduction and Terminology

The methods of anaesthesia described in this chapter are:

-

topical anaesthesia

-

jet injection

-

intrapapillary anaesthesia

-

intraosseous anaesthesia

-

intraligamentary anaesthesia

-

intraseptal anaesthesia

-

intrapulpal anaesthesia

-

transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation.

All of these techniques can be used in either jaw.

Topical Anesthesia

Topical anaesthetics may achieve beneficial effects prior to needle penetration. Such effects may be psychological or pharmacological. Factors that influence the pharmacological efficacy of topical anaesthetics include:

-

the agent employed

-

duration of application

-

site of application.

The agent

Different delivery vehicles are used to administer topical anaesthetics (Fig 6-1). These include:

-

aerosols

-

ointments

-

gels

-

lozenges

-

tablets

-

pastes

-

powders

-

solutions

-

impregnated patches.

Fig 6-1 Topical anaesthetics are available in a number of formulations.

Two aspects related to the agent should be considered in relation to efficacy: first the concentration and secondly the anaesthetic agent itself. Different formulations of the same anaesthetic drug need different concentrations to achieve a similar effect. For example, sprays require a higher concentration than patches. The transfer of the anaesthetic through the mucosa is concentration dependent.

A variety of agents are used as topical anaesthetics. The injectable anaesthetics used in the UK are exclusively of the amide group; this class of anaesthetic produces a very low incidence of allergic reactions. Ester local anaesthetics such as benzocaine and amethocaine are used as topical agents. The ester class are more likely to produce allergic reactions than the amides. There is little to choose between most of the different agents as far as efficacy is concerned. Both lidocaine and benzocaine have been shown to exert a pharmacological action when applied topically in the mouth. There is experimental evidence that EMLA cream (see Chapter 3) is more effective than lidocaine alone. This may be due to differences in the effective concentration of the drug. EMLA is not licensed for intraoral use at present.

Duration of application

The depth of penetration of the applied agent is governed by the duration of application. In some studies a 2.5-minute application has been shown to be ineffective yet the same material has achieved an effect at 5 minutes. Thus it may be necessary to maintain the agent in position for 5 minutes in order to achieve a pharmacological effect.

Site

The effectiveness of topical anaesthesia varies in different parts of the mouth. There is evidence that the mandibular buccal fold is more susceptible than the corresponding area in the maxilla. In the maxilla the buccal fold is more readily anaesthetised compared to palatal mucosa after topical application.

Although topical anaesthetics have been shown to reduce the discomfort of infiltration anaesthesia, there is no evidence that they decrease the discomfort of deep regional anaesthetic techniques such as inferior alveolar nerve blocks.

Uses

Normally, topical anaesthesia is used prior to needle penetration for conventional anaesthetic techniques. There are reports of soft tissue surgery procedures performed in the mouth under topical anaesthesia alone. In addition, some reductions in the response of dental pulps to electrical stimulation have been reported following application of topical anaesthesia to the overlying mucosa. Advances in this field should be encouraged. If reliable pulpal anaesthesia could be produced after topical application then needles could be eliminated from the dental local anaesthetic armamentarium. Imagine patient reaction to that!

Jet Injection

Jet injection has been used for many years in dentistry. The technique has been employed as a sole means of anaesthesia and as a method of reducing the discomfort of subsequent local anaesthetic injection. Jet injection works by forcing anaesthetic through mucosa under pressure (Figs 2-15 and 6-2). A recently described method uses anaesthetic powder. Local anaesthetic solution is employed in most other systems. Some devices accept dental local anaesthetic cartridges; with others the solution has to be drawn up into a reservoir in the injector. The head of the device is placed firmly against mucosa (Fig 6-2) and then the trigger released. This forces the solution through mucosa to produce anaesthesia. The technique has been shown to provide enough anaesthesia in some cases to allow extraction of teeth. On the other hand it is not 100% effective in reducing injection discomfort of needle penetration after surface anaesthesia with jet injection. The efficacy is dependent upon the concentration of local anaesthetic used. Occasionally the patient will experience haematoma formation at the site of use. Another disadvantage is that spillage of anaesthetic solution into the mouth tastes unpleasant.

Fig 6-2 A jet injection.

Intrapapillary Anaesthesia

Intrapapillary injections may be used to obtain localised anaesthesia and haemorrhage control during periodontal surgery. In addition they can be used as a means of obtaining palatal anaesthesia following buccal infiltration. This is particularly useful in children and is described more fully in Chapter 9.

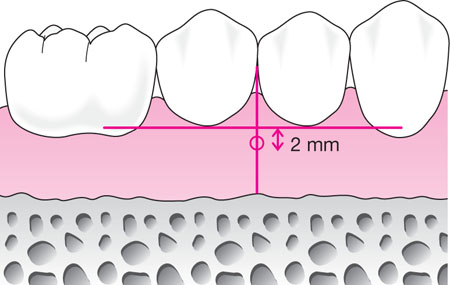

Technique

A short or ultrashort 30-gauge needle should be fitted to the syringe. The needle is inserted at the buccal aspect of the papilla; a site about 2 mm apical to the tip of the papilla is ideal (Fig 6-3). This target should be approached with the needle parallel to the occlusal plane and solution injected slowly; only a small amount of solution (around 0.1 mL) is required. Blanching of the papilla indicates successful deposition.

Fig 6-3 An intrapapillary injection.

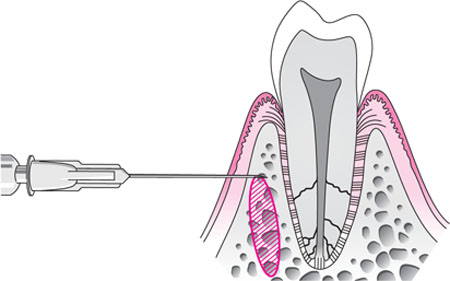

Intraosseous Anaesthesia

As the name indicates, intraosseous anaesthesia relies upon the deposition of anaesthetic solution directly into the cancellous space (Fig 6-4). Although the technique may be performed with conventional dental local anaesthetic delivery systems, the introduction of specialised equipment has made this method easier to carry out.

Fig 6-4 The intraosseous injection.

Technique

The point of penetration is identified (Fig 6-5). It should lie in attached gingiva and is determined by imagining two lines perpendicular to one another. The horizontal line passes along the buccal gingival margins of the teeth. The vertical line bisects the distal interdental papilla of the tooth that is being anaesthetised. The site of perforation is 2 mm apical to the intersection of these lines. If this is located within reflected mucosa an area of attached gingiva coronal to this is chosen. If the approach is made through reflected rather than attached gingiva the bony perforation in the alveolus may be difficult to locate with the needle unless a system with a needle locator is used (see below).

Fig 6-5 The point of penetration for the intraosseous injection is 2 mm below the intersection of the lines illustrated. The horizontal line traverses the gingival margins of the adjacent teeth and the vertical line bisects the interdental papilla.

Deposition of solution through reflected mucosa, although closer to the apex, does not improve the efficacy of intraosseous anaesthesia. Therefore, penetration via attached gingival is recommended. The area of perforation is infiltrated with 0.2 mL of local anaesthetic. The perforator is used one minute later when gingival anaesthesia has occurred. When using the specialised equipment the perforator is advanced through the anaesthetised gingiva and bone using a slowspeed handpiece (Fig 6-6a). A characteristic “give” indicates penetration through to the cancellous bone. Following removal of the perforator, the short (6 mm) 27-gauge needle is inserted through the perforation into the cancellous space (Fig 6-6b). About 1 mL of solution is delivered slowly (over a two-minute period). The technique should be avoided in cases of active periodontal disease, where there is limited attached gingiva or if there is little interradicular bone.

Fig 6-6a The perforator being used during an intraosseous injection.

Fig 6-6b The intraosseous injection being performed.

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses