Chapter 4

Problem Solving in the Differential Diagnosis of Bony Defects Resulting from Pulpal and Periodontal Pathosis

Problem-solving challenges and dilemmas that deal with the differential diagnosis of bone defects resulting from pulpal and periodontal pathosis addressed in this chapter:

“I have never found a pulp removed from a pyorrhetic tooth to be normal … where a pathologic pulp is present, a pyorrhetic condition cannot be cured by treatment applied exclusively to the external surface of the root, with no treatment of the pulp itself.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

“Interradicular periodontal lesions can be initiated and perpetuated by inflamed or necrotic pulps. Extension of the inflammatory lesions from the dental pulp apparently occurs through accessory or lateral canals situated in the furcation regions of premolars and molars.”

The relationship of disease processes coming from the pulp of the tooth to the supporting periodontium is a subject that has received much attention in endodontic literature for almost 90 years.

Controversies and Highlights of Disease Interactions

Pulp tissue degenerates after a multitude of insults—caries, restorative procedures, chemical and thermal insults, trauma, and some periodontal treatment. When products from pulp degeneration, in particular inflammatory exudates and bacteria, reach the supporting periodontium, many changes may occur, including a rapid onset of inflammation, lateral or furcation bone loss, tooth mobility, and sinus tract formation through the buccal mucosa or gingival sulcus. If this occurs in the apical region, a periapical lesion forms (see

Periodontal disease is generally a slow-developing process that may have a gradual atrophic effect on the dental pulp. Complete pulpal necrosis caused by periodontal pathosis, however, is uncommon. Changes in the pulp include chronic inflammation, localized tissue death (infarction), fibrosis, decrease in cellular populations, resorptions, local coagulation necrosis, or dystrophic calcification.

The most intimate and demonstrable relationship of the communication of inflammation between the two tissues is via the vascular system,

The main anatomic pathways must be considered as potential pathways in the exchange of inflammatory products and bacteria between the pulp and the periodontium (and vice versa) and include lateral/accessory canals that branch off the main root canal, open dentinal tubules (sometimes due to cemental agenesis), the presence of lingual grooves, removal of cementum during periodontal or restorative procedures or loss due to resorptive defects, and root or tooth fractures.

For intact teeth, the principle avenues of communication would be the main foramen, lateral/accessory canals, and dentinal tubules. In the clinical setting, however, there are few means to determine that these particular avenues of communication are actively involved in the exchange of inflammatory substances and/or bacteria. For our purposes, the pathophysiologic relationships that exist between the pulp and periodontium are less important than an accurate diagnosis or one based on the best clinical evidence available on clinical problems and lesions that present on a daily basis. In general, inflammation or bone loss in the periodontium caused by lesions of pulpal origin will heal following a wide range of endodontic treatments. These types of cases are seen as a radiolucent lesion around the root apex, in an isolated furcation that has no other etiology, or on the lateral surface of a root. Specific periodontal treatment in these cases is rarely if ever warranted. The vast majority of lesions of the periodontium do not affect the dental pulp. The incidence of cases in which a connection between a lesion of pulpal origin and one of periodontal pathosis is even suspected is small.

This chapter has three objectives: (1) to clarify the most important diagnostic characteristics of lesions of the periodontium, with emphasis on those that resemble the extension of pulpal pathosis to the supporting root tissues; (2) to clarify the distinguishing diagnostic characteristics of periradicular lesions of pulpal origin that resemble or are mistaken for periodontal defects; and (3) to discuss the characteristics of lesions that are the result of neither inflammation/infection of the pulp or periodontium, yet may share characteristics of both. Treatment suggestions will accompany the lesions described.

An Endodontic Perspective on Chronic Periodontitis

The etiology and pathophysiology of chronic periodontitis is extremely complex. Briefly summarized, lesions of the disease are the result of microbiologic and immunologic effects of a biofilm that forms on the surfaces of roots.

FIGURE 4-1 A, Typical radiographic presentation of periodontal bone loss on mesial of mandibular first molar. B, 5 years later, bone loss has progressed to a deeper level.

For the dentist/endodontist, the periodontal probe is absolutely indispensable to clinical diagnosis. During assessment of the periodontium, measurement of attachment loss is the standard by which progression or remission of the disease is assessed.

The normal periodontium is known to have fairly predictable dimensions.

Traditionally in routine periodontal examinations, probing depths have been recorded in six locations for each tooth: the mesial, midsurface, and distal of both the buccal and lingual surfaces.

Osseous defects resulting from chronic periodontitis are routinely found to be of varying depth but similar in form. Probing circumferentially across a broad root surface will usually indicate a gradual increase in depth until the deepest area of the defect is reached. Continuing past this point, the probing depths will then gradually decrease. The typical contours of crestal bone found in bony lesions of advanced periodontitis are illustrated in

Periodontal Lesions of Bone that Can Be Confused With Pulpally Induced Bony Lesions

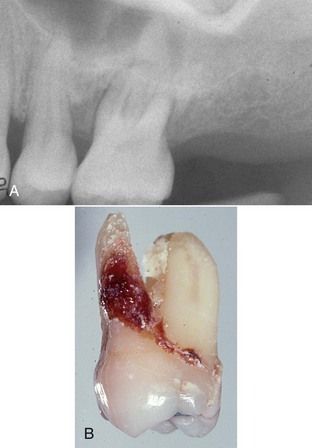

Bony lesions of periodontal disease are usually not difficult to distinguish from bony lesions of pulpal origin. Periodontal defects begin in the marginal periodontium, and even deep periodontal pockets are usually far removed from the root apex (

FIGURE 4-4 Lesions of advanced chronic periodontitis with severe bone loss do not generally involve the apex, as seen on the second molar. Lesion on first molar is endodontic, with a drainage tract coursing coronal and exiting near the furcation. Circumferential probings of first molar reflect a level of attachment consistent with bone levels seen on radiograph and do not involve the furcation. Prognosis for root canal treatment of first molar and long-term tooth retention is good. Second molar is hopeless periodontally, regardless of pulpal status.

Acute Periodontal Abscess

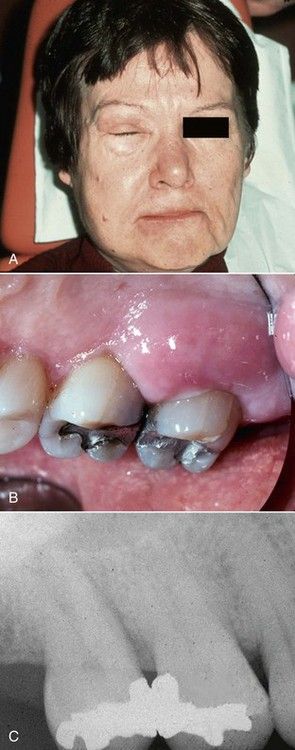

An acute periodontal abscess is clinically identical to many acute periapical abscesses of pulpal origin. The patient may experience severe swelling (

FIGURE 4-5 A, Acute facial swelling associated with periodontal abscess is identical to the swelling of acute periapical abscess. B, Clinical view of same acute periodontal abscess. C, Radiograph of periodontally involved teeth. Note bone loss between molars and lack of periapical involvement.

Diagnostic procedures usually begin with a good radiograph. In this case (see

Lesions of Chronic Periodontitis

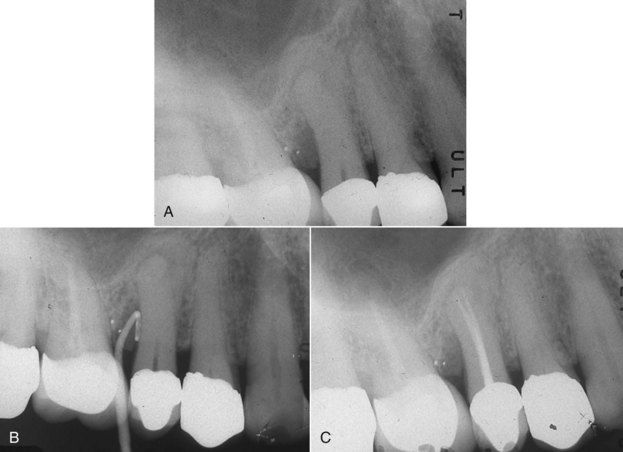

Bony lesions of chronic periodontitis are sometimes confused with lesions of pulpal origin because of a draining sinus tract. In

FIGURE 4-6 Sinus tract of periodontal etiology found in attached gingiva over maxillary left central incisor.

FIGURE 4-7 A, Periodontal probing depth normal interproximally. B, Probing depth normal in midlabial area. C, Deep probing pattern associated with periodontal bone loss. D, Radiograph of same lesion. Note absence of periapical involvement. E, Surgical exposure of periodontal lesion.

FIGURE 4-8 A, Sinus tract similar to

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

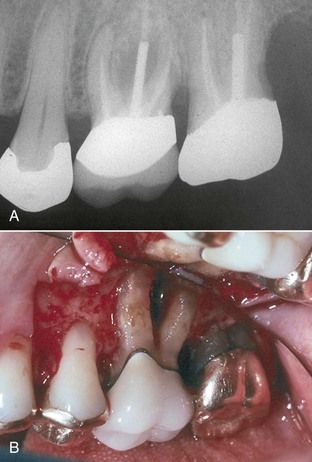

A 52-year-old male was seen for recurrent local swelling and drainage in the area of the maxillary right second premolar. Clinical examination revealed a draining sinus tract in the attached gingiva near the second premolar. A radiograph indicated that there was a widened apical periodontal ligament space consistent with a developing periapical lesion in addition to a deep periodontal defect interproximally on the distal (

FIGURE 4-9 A, Maxillary right premolar area with history of recurrent drainage suspected to be of pulpal origin. There is both apical and periodontal pathosis evident on the second premolar. B, Sinus tract exploration with gutta-percha cone, revealing source of drainage is the periodontal lesion. C, Completed root canal treatment will only resolve the periapical lesion. Periodontal surgery is also indicated to eliminate the pocket. This will resolve both associated infection and the drainage tract.

Solution

Sensibility testing was performed. No responses were obtained from the second premolar, and the first molar previously had root canal treatment. A sinus tract exploration was done by placing a gutta-percha cone in the tract and exposing an additional radiograph (see

Although there may be ample evidence of a general chronic periodontitis in the oral cavity, some localized areas may have developed extremely severe bone destruction. If periodontal defects extend to the apex, the radiographic lesion present may be confused with a periapical lesion of pulpal origin. The patient in

FIGURE 4-10 Localized lesion of advanced chronic periodontitis. Note tooth has been opened for root canal treatment that will have no effect on this lesion.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 57-year-old male with a history of recurrent swelling on the palatal aspect of the maxillary left first molar was referred for root canal treatment. The referring dentist noted a large periapical lesion encompassing the apex of the palatal root (

Solution

Sensibility tests should be performed early in the examination. In this case, results were normal—in fact, the tooth was hypersensitive to a cold stimulus. Periodontal probings indicated that there was bone loss to the apex of the palatal root and confirmed severe attachment loss around the other two roots. As in the previous case, root canal treatment would have no effect on this problem, so the tooth was extracted. In these cases, calculus deposits are commonly seen covering the entire root surface (see

Occasionally a periodontal bone lesion may resemble a periapical lesion and, at least radiographically, lack other obvious signs of generalized periodontitis.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 38-year-old male presented with a history of recurrent acute abscesses in the buccal vestibule adjacent to the maxillary left first molar. The radiograph showed a “classic” periapical lesion on the apex of the mesial buccal root (

Solution

Sensibility tests indicated normal responses on this tooth, confirming that this is not a pulpal problem. Periodontal probing revealed complete loss of attachment over the entire buccal surface of the root (see

Periodontal Lesions Involving the Furcation

Loss of bone in the furcation of a molar due to periodontal disease is sometimes difficult to distinguish from bone loss due to a necrotic pulp (communication via furcation canals)

Lesions Associated With Aggressive Forms of Periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis in young people, once known as juvenile periodontitis, affects less than 1% of the population.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses