4

Pediatrics and sleep-related breathing disorders

CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW

Sleep disorders are not exclusive to the adult population. Children and adolescents also may suffer from sleep disorders. However, sleep disorders are not as easily recognized in this group as compared to adults and therefore are frequently undiagnosed. The sleep problems are often manifested as behavioral issues, emotional concerns, or personal conflicts that are out of proportion to the actual event, such as family conflicts or stress.

The more common sleep disorders in children and adolescents involve sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD), difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep (i.e., insomnia), periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), or restless legs syndrome (RLS). There are other sleep disorders that may impact this age group, but the majority of them fall within these categories. SRBD is one of the major interests for the dentist.

Awareness of SRBD in the pediatric population dates back to the 1800s. A medical manuscript in 1884 indicated that mouth breathing had ill effects on children as well as adults.1

Another publication in 1889 noted that children presented with deafness appeared “backward and even stupid,” had headaches, and would mouth breathe.2 Also, in 1892 a medical document linked sleep and daytime performance in children with sleep-related upper airway obstruction.3 The author stated that the “child is very stupid looking,” that an “influence on mental development is striking,” that the child found it “impossible to fix the attention for long at a time,” and that “the expression is dull, heavy, and apathetic.” Also recognized in that document were symptoms of headaches and listlessness. Others in the early half of the 1900s also found a correlation between sleep, airway obstruction, and daytime functioning. The current scientific literature is abundant with evidence that confirms these earlier anecdotal findings.

An increasing awareness in the last 20 years regarding the importance of recognizing pediatric sleep issues is demonstrated by the increase in the number of articles and textbooks that are devoted to the topic. During that period, there has been a 1,226% increase in the number of published articles related to this area.4

FREQUENCY OF SLEEP DISORDERS IN THE PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT POPULATION

Between 20 and 50% of the pediatric and adolescent population may have a sleep disorder.5–8 This frequency is significant and often results in parental concern because of the clinical impact on the child’s behavioral, physical, and mental health. Unfortunately, sleep disorders in this age group are not recognized and are therefore undiagnosed.

Many times the presentation of insomnia is secondary to other situations that can impact sleep, and, as such, it may actually be the presenting symptom of SRBD. The presence of insomnia, oftentimes described as individuals being poor sleepers or having insufficient sleep, may be 12–33% in this younger population.7, 9, 10

SRBD frequency in children, especially with regard to snoring or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), has been studied the most. OSA is estimated to occur in 1–3% of children,11 and snoring is believed to occur in 3–12% of this population, with occasional snoring being present about 20% of the time and habitual snoring being present about 10% of the time.12

More recently, the presence of RLS and PLMD in children has been investigated. Although the frequency is not specifically known, one study reported that about one-third of 138 adults who reported symptoms of RLS also indicated that these same symptoms were present before age 10.13

The key finding related to RLS in the younger age group is the association between RLS and inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).14

Unlike adults, these sleep disorders may present themselves differently in this younger population. Accordingly, the sleep disorder may not be considered in conjunction with other complaints that a child may have or with signs that are evident, and thus may be overlooked. Interestingly, the utilization of health care by children with a sleep disorder is 2.6 times as compared to their matched controls.15

There are many health-related conditions that may be associated with a sleep disorder in a child or adolescent, but these findings may go undetected because sleep problems in this age group are oftentimes not a primary consideration (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Health-related conditions associated with sleep-related breathing disorders in children and adolescents.

| Depression | Diabetes type 2 | Allergy |

| Enuresis | Increased triglycerides | Headaches |

| Asthma | Tired/irritable ADD/ADHD | Obesity |

In addition, there are congenital conditions that indicate that a child may be at a higher risk for a sleep disorder and specifically SRBD, especially OSA (Table 4.2).

Children that present for dental care may have clinical findings that would suggest that they are at risk for SRBD.

RECOGNITION OF SLEEP DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

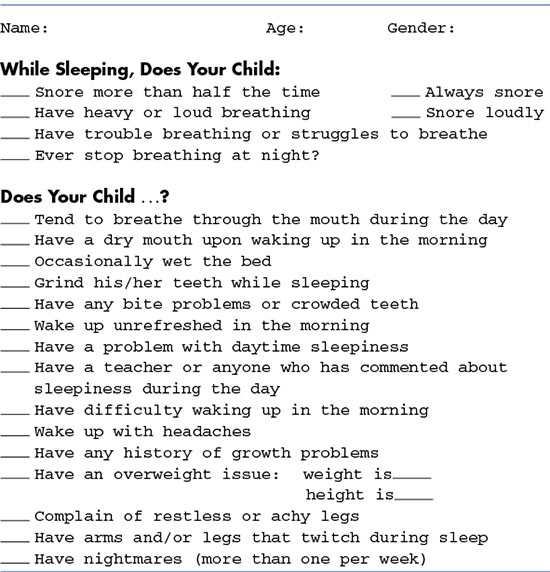

The recognition of a sleep disorder in children and adolescents requires the use of proper questioning techniques as well as the identification of related signs of these disorders. If a sleep disorder is suspected, then a simple questionnaire can be used to determine if the individual is at risk for a sleep disorder, but the questionnaire itself cannot be utilized as a diagnostic tool. On suspicion, a more formal referral to the child’s physician or a sleep specialist is indicated.

A number of these questionnaires have been developed over the years. The Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale is composed of eight questions that are most applicable to middle-school children, and it assesses the relationship between daytime sleepiness and school-related outcomes, mainly educational achievement.16 The Pediatric Sleep-Disordered Breathing OSA-18 questionnaire evaluates quality-of-life issues related to OSA, and it looks at the symptoms as well as sleep disturbances and daytime functioning.17 Another instrument, the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire, has been designed as a generalized-type questionnaire that covers a wide range of issues related to sleep disruption. Table 4.3 represents a generalized pediatric sleep questionnaire.

Table 4.2 More common congenital conditions that predispose the child to sleep-related breathing disorders.

Source: Adapted from Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Elsevier/Saunders. 2005; 23.

| Down syndrome | Pierre Robin syndrome |

| Prader–Willi syndrome | Achondroplasia |

| Asperger syndrome | Chiari malformation |

Table 4.3 General pediatric sleep questionnaire

The Cleveland Adolescent Sleepiness Questionnaire is a more recently developed instrument and it applies to a variety of ages and sleep disorders.18 This questionnaire may be used freely, and the authors request that the results be shared with them in an effort to refine the questionnaire over time.

A sleep disorder may need to be considered when a child presents for dental care, particularly if there are risk factors present that might indicate such a disorder.

Sleep disruption has a strong correlation to the presence of headache in both the adult and younger age group populations. One of the chief complaints that may indicate the presence of a possible sleep disorder is headache, particularly in the adolescent population.19 For patients who had headaches, there were also complaints about sleep, which involved insufficient sleep, being sleepy during the day, having trouble falling asleep, and the presence of awakenings at night. When headaches are present, it is necessary that the clinician consider and investigate the possible existence of sleep problems as well. The most common recommendation then would be to give instructions for good sleep practices, also known as sleep hygiene.

Sleep-related breathing disorders

SRBD consists mainly of snoring and OSA. In a child or even the adolescent patient, the presentation of snoring may appear more like heavy breathing. For an apnea or any cessation in breathing during sleep to be identified, a parent or someone else would need to observe this first hand. Therefore, the presence of apnea, like snoring, often goes undetected because most children sleep alone or in a separate room.

Another type of SRBD is termed upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS), although it is not officially recognized in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition (ICSD-2). UARS may appear to be OSA; however, the key differences are that the respiratory events of UARS are related to an arousal and there are no distinct apneas or hypopneas.20 In addition, the level of blood oxygen, also known as oxygen saturation, does not decrease with UARS.

The recognition of SRBD in a child can also be related to simply mouth breathing alone.21 This type of breathing pattern during sleep appears to have an almost identical affect on the quality of sleep, and thus may result in very similar symptoms as a definitive SRBD.

The presentation of symptoms or signs associated with SRBD in children can be recognized on the basis of either the daytime or nighttime findings (Table 4.4).

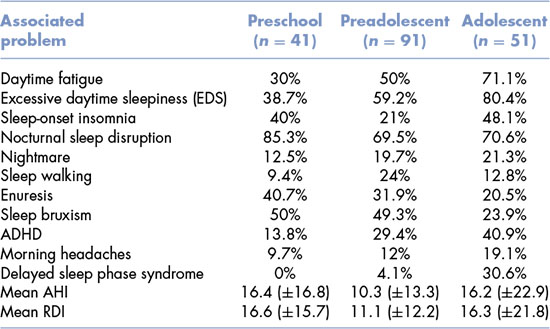

One study outlined the presentation of symptoms associated with SRBD that were divided into three age groups: preschool, preadolescent, and adolescent (Table 4.5).22

Because SRBD has not been a typical or usual consideration when evaluating pediatric patients, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a guideline for the diagnosis and management of SRBD in this age group of patients.23 The guidelines recommend that

Table 4.4 Symptoms and findings at nighttime and daytime in children with sleep-related breathing disorders.

| Nighttime | Daytime |

| Snoring | Neurocognitive impairment |

| Bruxism | ADHD and ADD |

| Awakenings | Hyperactivity |

| Mouth breathing | Behavioral issues (irritable) |

| Nightmares | Tired/poor school performance |

Table 4.5 Clinical manifestations of sleep-related breathing disorders in three age groups—up to the age of 18; based on the review of 189 charts.

Source: Adapted from Kim J, Won C, Guilleminault C. The clinical manifestation of sleep-disordered breathing in children and adolescent. Sleep. 2007; 30(Abstract Supplement):86.

- all children be screened for snoring;

- in the presence of a cardiorespiratory health condition, the child should have a more extensive evaluation;

- diagnostic evaluation be conducted to determine if the risk for OSA is present, most often resulting in an overnight sleep study.

This type of guideline can easily be implemented in the dental setting by anyone who treats pediatric patients.

Treatment for OSA in children is most often a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy when those anatomical structures are enlarged because of their potential to be interfering with the airway. This is the first line of treatment and often the most successful. Following this surgical intervention, in many instances the symptoms are reversed and no further treatment is indicated.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Clinically, at the time of an oral evaluation, there are some signs that a patient may be at risk for a sleep disorder and specifically SRBD. Prior to the clinical evaluation, the history is a critical component in the recognition process.

There are facial features that indicate a risk for SRBD. The most common of these are the following:

- Adenoidal faces: This is a condition where the face is rounded with an often blank stare (Figure 4.1).

- Allergic shiners: These are the dark circles that are often found under the eyes. They are related to a reduction or absence in nasal breathing with an increased amount of mouth breathing (Figure 4.2).

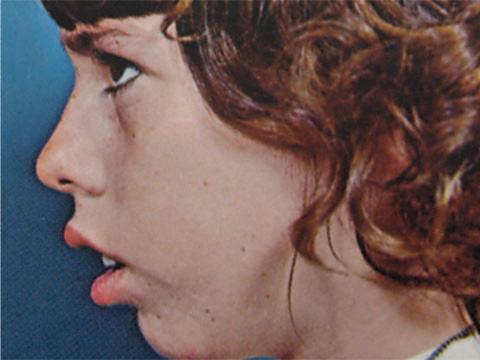

- Poor or inadequate lip seal: In this situation, the lips are found to be apart with the appearance of difficulty in the ability to maintain a lip seal (Figure 4.3).

- Small nares: The opening to the nasal airway is small and appears constricted (Figure 4.4).

- Nasal crease: This is a horizontal line that goes across the nose above the tip of the nose. Oftentimes this may be associated with the allergic salute, which is a gesture associated with a repetitive action of wiping the nose due to the feeling of a constant drainage. This clinical feature may be associated with an allergy (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.1 An example of an adenoidal face. (Meyer B and Marks MD. Stigmata of Respiratory Tract Allergies. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Co. 1977. Used with permission from Pfizer Inc.)

Figure 4.2 An example of allergic shiners. (Meyer B and Marks MD. Stigmata of Respiratory Tract Allergies. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Co. 1977. Used with permission from Pfizer Inc.)

Figure 4.3 An example of poor or inadequate (open) lip seal. (Meyer B and Marks MD. Stigmata of Respiratory Tract Allergies. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Co. 1977. Used with permission from Pfizer Inc.)

Figure 4.4 Small nares.

Figure 4.5 An example of nasal crease; note the arrow pointing to the line across the nose. (Meyer B and Marks MD. Stigmata o/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses