7

Evaluation by the dentist

CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW

The dentist is called on today, more than ever, to be cognizant of related health care issues of their patients and not just of their dental and oral health status. This understanding and subsequent formal training in dental education began several decades ago with the recognition of hypertension when the blood pressure was taken at an initial visit or at a periodic visit for reevaluation, such as a dental hygiene visit. When the blood pressure was elevated, the patient was advised to contact their physician and have this evaluated more thoroughly. This heightened awareness led to the recognition of many people who were at risk for hypertension and who otherwise would have been undetected.

More recently, the association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease has been identified, and more aggressive steps are being taken clinically to resolve the periodontal condition in order to reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease. More than any other health care provider, oral cancer screening is another action that the dentist implements during the initial and follow-up care visits. Other examples are related to the recognition of oral conditions associated with systemic illnesses such as diabetes, leukemia, and many of the autoimmune diseases (e.g., Sjogren’s syndrome).

Sleep disorders, and particularly obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), are no exception. Not only are sleep disorders prevalent in the general population, but they also have a potential for significant impact on an individual’s health as well as on society. Sleep disorders may impair one’s quality of life and daily performance relative to schooling, driving or operating any other machinery, the workplace, and relationships.

The role of the dentist in the recognition of patients at risk for OSA and other sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD), such as snoring, is now well established. The dentist is just as likely to identify a patient who is at risk for OSA as is the physician.1 However, a study found that dentists had a general deficiency in their ability to recognize a patient at risk for OSA, and they also knew very little about the use of oral appliance (OA) therapy for the management of SRBD.2 Also, only an estimated 16% of the dentists were taught anything about SRBD in dental school, and about 40% knew very little about OA therapy for the management of OSA. The study demonstrated the need for more education related to OSA and the use of an OA as an option for the management of the patient diagnosed with OSA.

WHAT THE DENTIST SEES THAT INDICATES THE RISK FOR SRBD

The dentist as well as the dental hygienist sees patients regularly who have signs of SRBD. However, unless the practitioner is knowledgeable of and recognizes the potential for these findings to suggest that there is a risk for SRBD, the sleep disorder may go undetected. Many of the conditions that may be identified by both the dentist and the dental hygienist that may indicate a risk for SRBD and health-related issues are commonly observed findings. Unfortunately, these findings often may be evaluated on their own merit as being stand-alone, and thus they may not be considered as potentially being related to some other health issue.

Once any of these conditions are recognized, then it becomes imperative to do the following: (1) determine if the risk for snoring or OSA is present, (2) inform the patient of the findings, and (3) consult with them regarding the appropriate measures needed for a complete diagnosis and management plan.

Many intra- and extraoral conditions have an association with risk for SRBD that warrant in-depth consideration (Table 7.1).

ASKING THE PROPER QUESTIONS

The addition of a few questions to the existing health history questionnaire is an important element of the data collection phase. These questions may not only uncover an individual who is at risk for snoring or having OSA, but they may also assist in the identification of someone who has been previously diagnosed with SRBD.

Table 7.1 Conditions that indicate the risk for a sleep-related breathing disorder: sleep apnea and snoring.

| Observed condition | What this may indicate |

| Wear on the teeth | Indicative of sleep bruxism |

| Scalloped borders (crenations) of the tongue | Found to correlate with an increased risk for sleep apnea12 |

| Enlarged tongue | Increased potential for upper airway obstruction |

| Coated tongue | Possible gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| Enlarged, swollen, or elongated uvula | Increased potential for snoring or sleep apnea |

| Large tonsils | Higher incidence of airway obstruction |

| Narrow airway | Greater risk for snoring or sleep apnea |

| Gingival recession and/or abfraction | Greater potential for sleep bruxism (grinding or clenching) |

| Tongue obstructs view of airway (Mallampati score) | The greater the obstruction, the higher the potential for snoring and sleep apnea |

| Chronic mouth breather (poor lip seal) | Blocked nasal airway; more likely to snore |

The basic questions that the dentist might include in the initial patient history form are the following:

- Do you or have you been told you snore when sleeping?

- Are you tired upon awakening from sleep or during the day?

- Do you fall asleep or are you drowsy in inappropriate situations such as in meetings, at movies, at church, or in social situations?

- Are you drowsy when driving?

- Do you have headaches in the morning?

If the response to any of these questions is positive, then additional questioning for a more comprehensive understanding of any potential sleep disorders may be necessary.

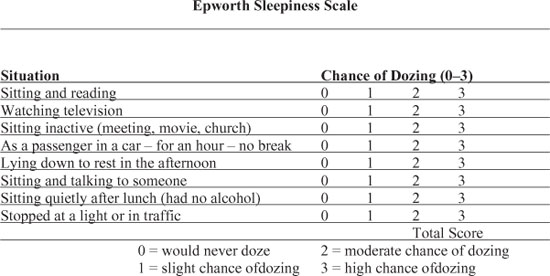

To further recognize a patient who may be at risk for OSA, the use of a common questionnaire known as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is utilized. The ESS identifies patients who are experiencing symptoms related to daytime sleepiness, which suggests the risk for OSA (Figure 7.1).3 This eight-item survey can be easily completed by the patient, and the scored results assist the practitioner in considering the appropriate course of action that may be advisable, which, most often, is a referral for a sleep study (polysomnogram) or to the patient’s physician for further evaluation.

Figure 7.1 Epworth Sleepiness Scale—modified and adapted from original version. (Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991; 14:540–545.)

Interpretation of the ESS score is a common means of communication within the sleep medicine field regarding the risk for OSA. As the total score approaches 9, the risk for OSA increases.4 As the total score becomes greater than 9, then the risk factors are considered to be even more significant. An elevated score, though, is not always definitive for OSA and is also not indicative of its severity. The results from the ESS also need to be considered in light of other clinical and patient history findings.

The second portion of the ESS evaluates the patient’s behavior during sleep and more specifically some of the well-recognized characteristics associated with OSA. Snoring and its severity are assessed along with conditions associated with snoring that may suggest an increased risk for OSA such as waking up gasping for air or experiencing a choking sensation during sleep. If snoring is the only recognized condition along with the ESS total score being less than 9, then the risk for OSA may be less, but this is not always the case.

CLINICAL SCREENING FOR SRBD

Once it has been determined that a patient is at risk for SRBD, it may be advisable to perform a sleep disorder screening examination. In most instances, a significant amount of clinical information regarding the patient’s dental and medical status and history has already been collected. The screening evaluation will supplement the existing record with documentation that is designed to identify relevant conditions that support the possible risk for SRBD, in particular for OSA.

Table 7.2 reflects the progression of steps that might be considered to assess the patient who is at risk for SRBD.

Table 7.2 Steps for assessment of the patient at risk for a sleep-related breathing disorder and sleep apnea.

Source: Treatment Sequencing. Handout for the UCLA School of Dentistry Dental Sleep Medicine Mini-Residency; 2009.

| Step 1: | Recognition of existing risk factors (Table 7.1) |

| Step 2: | Positive response(s) to the health history questions |

| Step 3: | Completion of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| Step 4: | Discussion with the patient regarding the positive responses from above |

| Step 5: | Reappointment for clinical screening evaluation |

| Consultation to discuss findings | |

| Make recommendations for management plan | |

| Management options | |

| • Refer to patient’s physician for further evaluation | |

| • Refer for a sleep study |

There are a number of components that should make up an SRBD screening evaluation, including SRBD history, review of medical history, review of current medications, temporomandibular disorders (TMD) assessment, oral airway evaluation, nasal airway evaluation, and subjective airway testing.

SRBD history

The SRBD history is designed to obtain patient’s history-related findings that are specific to SRBD, such as the following patient symptoms or previously diagnosed conditions:

- Snoring

- Sleep apnea

- Low energy

- Daytime sleepiness/tired

- Difficult to concentrate

- Previous or current use of positive airway pressure therapy

- Previous surgery for SRBD

- Mood swings/irritable

- Feel depressed

- Headaches

- Bruxism (grinding and/or clenching)

Review of medical history

The patient’s medical history may be indicative of an underlying sleep issue. A number of preexisting medical conditions may suggest an increased risk for SRBD, particularly OSA, such as the following:

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular disease

- Headaches

- Respiratory conditions (especially asthma)

- Diabetes

- Gastroesophagal acid reflux disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Allergy

Review of current medications

The patient’s current medications need to be reviewed. There may be prescription medicines that are being used for the management of a medical condition, yet the condition may be related to a sleep disorder. In addition, many medications may have an impact on the patient’s sleep.

Medications and sleep

Almost all medications that are taken can impact sleep in some manner. Table 7.3 outlines some of the more common medications that are frequently encountered in a dental practice and which may impact sleep.

Not all patients have similar responses to medications, and they may not experience an adverse effect on their sleep. Also, patients may be taking medications for a particular health issue, and this may also be an indicator that a sleep disorder is present but may have been overlooked or not considered. In addition, there are many medications that are used to promote and improve sleep.

Medications by class associated with sleepiness

As reported in clinical trials and case reports

- Antihistamines

- Anti-Parkinson agents

- Skeletal muscle relaxers

- Opiate agonists

- Alcohol

Natural or alternative medications

- Ginsing

- St. John’s Wort

- Valerium

- Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

- Ephedra

- Vitamin C

Medications associated with insomnia

- Amphetamines

- Caffeine

- Nicotine

- Corticosteroids

- Theophyline

Table 7.3 Effect of common medications on sleep.

Sources: Adapted from (1) Lee/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses