Microbiology of Periodontal Diseases

Peter M. Loomer, Based on the original work by

and Dorothy J. Rowe

• Describe the development of supragingival and subgingival plaque biofilms.

• Compare the composition of supragingival and subgingival plaque biofilms.

• Describe the role of saliva in pellicle formation.

• Define the mechanisms for bacterial plaque biofilm adherence to tooth surfaces.

• Describe the influence of bacterial surface components (e.g., capsules, appendages) on bacterial colonization and coaggregation.

• Discuss plaque biofilm microbial succession in terms of oxygen and nutrient requirements and bacterial adherence.

• Compare the nonspecific and specific plaque hypotheses.

• Describe and classify the specific bacteria associated with the major periodontal infections: gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, localized aggressive periodontitis, generalized aggressive periodontitis, and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and periodontitis.

• Define the bacterial characteristics that contribute to their virulence.

• Describe the significance of dental plaque biofilm to dental hygiene practice.

The presence of dental plaque is essential in the initiation and progression of gingivitis and periodontitis. A critical role of the dental hygienist is the instruction of patients in proper oral hygiene practices to remove plaque as a preventive measure against periodontal disease and dental caries. Studies evaluating the relationship between oral hygiene and periodontal disease have shown that poorer plaque control correlates to a greater prevalence and severity of periodontal disease.1 With improved oral hygiene practices, however, there is less plaque and therefore decreased gingival inflammation and disease.

In the mid-1960s, researchers began to recognize the significance of plaque in the disease process. Experiments showed that when patients did not clean their teeth, and plaque was allowed to accumulate over time, inflammation of the gingival tissues occurred.2 When plaque control was resumed, the inflammation decreased and the tissues returned to a healthier state.3 Thus, dental plaque biofilms play critical roles in the etiology of periodontal diseases, and a thorough understanding of their composition and mechanisms of formation is essential in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases.

General Characteristics of Plaque Formation

Dental plaque biofilms are defined as accumulations of microbes on the surface of the teeth or other solid oral structures, not easily removed by rinsing. Dental plaque biofilms are different than material alba, which is loosely adherent bacteria and tissue debris that can be easily removed by the mechanical action of a strong water spray. A dental plaque biofilm is a complex, naturally occurring organized dense film of microorganisms bound in glycocalyx (the sticky polysaccharide matrix they produce) and other organic and inorganic products. The glycocalyx contains a network of channels and canals within the biofilm that allow for exchange of nutrients among various microbes and for the removal of their waste products. The complex biofilm structure also provides some protection for its resident microorganisms from invasion by outside intruders including other bacteria, antimicrobial drugs, and antiseptic rinses. Thus, both the nutritional and protective roles of the biofilm help it to thrive. For this reason, physical removal of dental plaque biofilms by daily brushing, interproximal cleaning, and periodic professional cleaning are essential for maintaining and restoring gingival and periodontal health.1

Bacterial Characteristics

Dental plaque biofilm consists mostly of bacteria. One mm3 of plaque biofilm, weighing about 1 mg, may contain more than 1010 bacteria, of which there may be several hundred species. Plaque biofilm is not a random accumulation of assorted types of bacteria but a specific and complex arrangement based on bacterial characteristics.4 To help understand how plaque biofilm forms, this section reviews some important microbiologic concepts that are used to classify or describe bacteria.

Cell Wall Characteristics

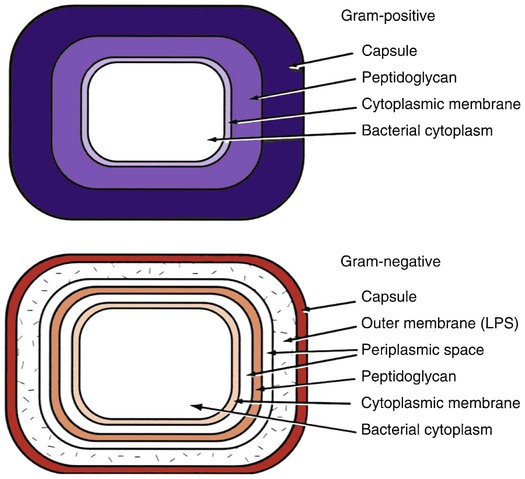

The cell walls of bacteria may contain structures and compounds that help them survive and cause damage to the patient’s tissues. Bacteria are classified by laboratory procedures as either gram-positive or gram-negative based on a staining technique that causes gram-positive organisms to stain violet (purple) and gram-negative ones to stain safranin (red). The structures of these cell walls are presented in Figure 4-1.

Note the larger glycan layer in the gram-positive cell wall. The outer membrane of the gram-negative cell wall contains lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin). (Courtesy of Dr. P.W. Johnson.)

Characteristics of Gram-Positive Bacteria

As seen in Figure 4-1, the capsule is the outer surface component of gram-positive bacteria. The glycocalyx (sticky extracellular matrix, or slime layer) is a loose, gel-like polysaccharide substance around the bacteria that is important in bacterial adherence (attachment) to the tooth surface and aggregation.

Cell Surface Appendages

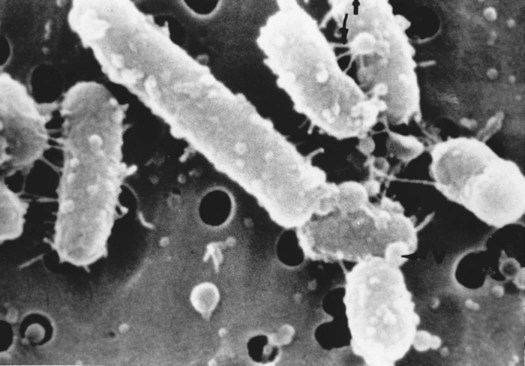

Cell surface appendages are important in the attachment of bacteria to tooth surfaces and to each other through bacterial adherence. Fimbriae, or pili, are small proteins that are attached to the external surface of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. They mediate the adherence process to hydroxyapatite. Figure 4-2 shows an example of pili on bacterial cell surfaces. Flagella are long, fine, wavy filamentous structures that are used for bacterial movement. Bacteria may have single or multiple flagella, arranged at either or both ends or distributed around the cell.

Classification of Periodontal Bacteria

Bacteria are classified based on their characteristics, some of which have been described here. Box 4-1 contains the classification of common periodontal bacteria based on these characteristics.

Oral Microbial Ecosystems

Dorsum of the Tongue

The dorsum of the tongue has a highly irregular surface consisting of several types of sensory papillae and foramen. The majority of the microorganisms on the tongue are gram-positive members of the Streptococcus family, including Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus sanguis. Many gram-negative bacteria associated with halitosis (bad breath) and periodontal disease are also found in the normal oral microbiota of the tongue, including Porphyromonas gingivalis. Some studies have attributed as much as 50% of bad breath to plaque biofilm on the dorsum of the tongue.4

Tooth Surfaces

On the basis of their relationship to the gingival margin, tooth-adherent plaque biofilms are classified as supragingival or subgingival. Supragingival plaque biofilm is deposited on the clinical crowns of the teeth, whereas subgingival plaque biofilm is located in the gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket. Small amounts of supragingival plaque biofilm are difficult to detect clinically without placing a disclosing solution or dye on the teeth, or scraping the tooth surfaces with an instrument. As plaque accumulation grows, it becomes visible as a white-yellow mass, as seen in Figure 4-3. Supragingival plaque biofilm forms in sites that are protected from the normal cleansing action of the tongue, cheek, and lips. This includes surfaces along the gingival margin of the tooth and the occlusal pits and fissures. Subgingival plaque biofilm can only be seen when it is removed from the pocket with an instrument. Plaque biofilm deposits also form on orthodontic appliances and permanent and temporary restorations, including implants, fixtures and restorations, fixed and removable partial dentures, and full dentures. It is extremely important to instruct patients on how to clean all these surfaces well.

Note the yellowish accumulations on the facial and interproximal surfaces of these mandibular teeth. The dark ring appearing on the facial side of the incisor is plaque that has absorbed pigment from oxidized blood products and is mineralizing into calculus. The redness of the tissue is directly related to the pathogenicity of the plaque, which has caused an intense inflammatory response.

Supragingival Plaque Formation

The development of dental plaque is a complex and dynamic process. In-depth, detailed discussions of this subject are reviewed by Liljemark and Bloomquist,3 Kolenbrander and London,5 Jakubovics and Kolenbrander,6 and Teughels et al.7 Plaque forms in stages as described next.

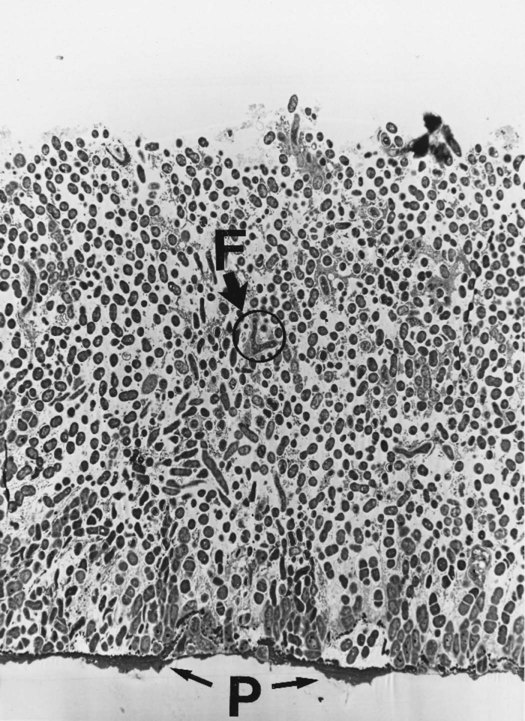

Step 2: Initial Bacterial Colonization of Pellicle

The initial plaque biofilm that forms on the pellicle is composed of mainly gram-positive, coccal, facultative anaerobic bacteria, largely streptococci, as seen in Figure 4-4. The first organisms adhere and form a monolayer of cells, either individually or in small groups. During the next few hours, the attached bacteria proliferate and form small colonies. These microcolonies of cocci usually form a series of columns that extend out from the pellicle, as seen in Figure 4-5. Bacilli and filament-shaped bacteria are usually aligned perpendicular to the tooth surface, often attached to the surface of the predominantly coccal flora. As the colonies expand, they meet and join together to form a continuous bacterial mass.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses