4

Immunological disease

Introduction

The human immune system comprises multiple physical, chemical and cellular components to protect the individual from disease. The primary function of the immune system is to protect from infection. Disease may result, however, when parts of the immune system are absent (immunodeficiency) or react against inappropriate things such as drugs and food (allergy) or the body’s own tissues (autoimmunity).

Traditionally, the components of the immune system have been classified as innate or adaptive (Table 4.1). The innate immune system components provide a constant level of protection. It is the first defence encountered by microorganisms. The adaptive immune system provides specific protection from the multitude of potential pathogens in the external environment. The adaptive immune system has a long-lasting immunological memory. It is so named because it adapts over the individual’s lifetime to infections with an organism. While the individual components of the immune system are described separately and classified into the innate and adaptive systems, it should be clear that these individual elements work closely together to protect the body from infection and provide long-lasting immunity to microorganisms already encountered.

The first part of this chapter gives an account of the basic components of the normal function of the immune system. The aim is to provide sufficient basic science for an understanding of the clinical problems that are addressed later in the chapter. If further details are required, the reader should consult a more detailed basic immunology text.

Overview of a normal immune response

When a microorganism enters the body through the skin or mucous membranes, the first defences encountered are those of innate immunity. These defences are constantly present and do not change following subsequent exposure to the organism. Intact skin, enzymes in tears, saliva, and acid in the stomach all provide barriers to infection.

If the barriers are breached, then the organisms can be targeted by cellular and non-cellular components of the innate immune system. Phagocytic cells are part of the innate immune system. They are able to engulf microorgansims and destroy them. Phagocytic cells include long-lived cells such as macrophages and short-lived cells such as neutrophils.

The complement system is also part of innate immunity. Complement is a series of 26 proteins circulating in the bloodstream. Following activation by microorganisms they form a cascade of proenzymes, the activation of each catalysing the activation of subsequent downstream components. Complement protects against infection by:

- Lysing infected cells

- Attracting phagocytic cells to the site of infection (chemotaxis)

- Coating the surface of the microorganism so that it is more likely to be destroyed by phagocytic cells (opsonisation).

If the innate immune system fails to control the infection, then specialised cells called antigen-presenting cells move from the site of infection to a specialised area (a lymph node) where an adaptive response is activated.

Table 4.1 Components of innate and acquired immunity

| Innate immunity | Adaptive immunity |

| Phagocytic cells | T cells |

| Complement | B cells |

| Barriers (see text) |

Within the lymph node, the cells of the adaptive immune system, the T and B cells, interact. B cells are activated to make antibody and T cells are activated to help the B cell (also known as T helper cell (Th cell) or CD4+ cell) or to kill infected cells (also known as cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) or CD8+ cells). The adaptive response takes time to be activated and therefore there is a delay before the immune system can initially respond. However, the adaptive immune system can modify its response on subsequent exposure to the organism so that long-lived memory cells can respond faster and more efficiently.

What is immunodeficiency?

Immunodeficiency occurs when one or more components of the immune system are defective or absent. This can be divided into primary causes, which patients are born with, or those secondary to events or disease processes occurring throughout life. All primary immunodeficiencies are rare. The majority of patients are diagnosed in childhood. A significant number of patients, however, do not develop symptoms until later in life and the diagnosis is often delayed for many years. This results in significant morbidity and increased mortality. It is important to be aware of these conditions and to refer to or discuss with the local immunology department if there are any concerns. Immunodeficiency is classified in Table 4.2.

What are the consequences of immunodeficiency?

Infection

If parts of the immune system are absent, then the body is unable to defend itself from infection. Despite significant overlap between the functions of parts of the immune system, some aspects have specific roles in defence against certain types of microorganisms. For example, B cells make antibodies. Antibodies can destroy organisms that live outside cells as antibodies cannot enter cells. If a patient is unable to make antibodies, they are unable to defend themselves as effectively against microrganisms that live outside cells.

Table 4.2 Classification of immunodeficiency

| Inherited/primary immunodeficiency |

|

|

|

|

|

| Acquired/secondary immunodeficiency |

|

Table 4.3 Warning signs of immunodeficiency

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Autoimmunity and malignancy

Immunodeficient patients can also be prone to malignancy and autoimmune disease as they have lost regulatory and surveillance cells that keep the immune system in check.

What are the symptoms and signs of immunodeficiency?

Patients with immunodeficiency usually experience recurrent and/or serious infections. These infections may also be persistent and difficult to treat, such as persistent oral candidiasis. Infections may occur with unusual or rare organisms in sites where this type of infection is not usually seen. Following recurrent infections, damage in specific organs may occur, e.g. bronchiectasis after repeated chest infections. Patients may also develop findings consistent with more widespread immune dysregulation such as autoimmune disease, e.g. vitiligo (patches of skin depigmentation) or hypothyroidism. Ten warning symptoms of immunodeficiency are shown in Table 4.3.

Examples of specific primary immunodeficiencies which may be seen in dental practice

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID)

CVID is a form of antibody deficiency disorder. The cause is unknown, although it is thought to be due to multiple gene defects. Patients present with recurrent bacterial infections and may present at any age. Treatment is lifelong, with antibody replacement therapy in the form of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy given every 2–3 weeks or subcutaneous immunoglobulin therapy administered weekly. Once on treatment, the risk of infection is reduced, but treatment with antibiotics may still be required for breakthrough infections.

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS)

WAS classically affects males. It is an X-linked disorder associated with eczema, low platelet counts and recurrent infections. These patients are at substantial risk of bleeding following dental treatment. In addition, antibiotic prophylaxis is required. Further management of these patients should be through liaison with the local immunology department or dental hospital.

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC)

CMC is a rare condition that affects both males and females. It presents with chronic candidal infection of the skin and mucous membranes. There may be an associated autoimmune endocrine deficiency. Management is through the local immunology department and can be challenging, with the need for regular antifungal treatment at high dose and for prolonged periods.

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)

CGD usually presents in childhood with recurrent deep abscesses. The underlying immunological defect is a failure of the neutrophil oxidative burst and subsequent killing of organisms. Patients develop recurrent deep-seated abscesses which may be in unusual sites. They also develop gingivitis and tooth loss.

Deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor (hereditary angioedema)

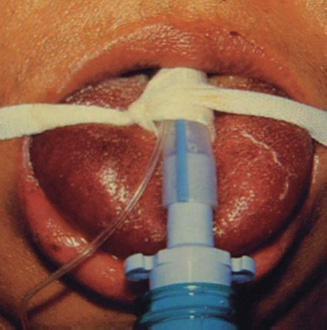

Defects of the control protein C1 esterase inhibitor may be inherited and result in uncontrolled activation of the complement pathway. Patients develop symptoms of recurrent deep swelling with exposure to minor trauma, or stress such as dental treatment. They can develop fatal laryngeal oedema (Fig. 4.1). Urticaria does not occur in this condition. The treatment of acute attacks is replacement of the enzyme. Patients require long-term treatment with androgenic steroids and tranexamic acid. Patients with this condition should be discussed with the local immunology department prior to dental treatment as they may require premedication with C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate.

Figure 4.1 A patient with C1 esterase deficiency. The patient was intubated to maintain the airway due to gross oedema.

Implications of immunodeficiency in dental practice

- Take a history

Check for recurrent infections; family history (genetic); check for drugs

- On examination

Look for candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, severe gingivitis, tooth loss, mouth ulceration, dry mouth, absent tonsils

Skin changes (vitiligo, alopecia, telangiectasia).

Common conditions can be features of immunodeficiency

Oral candidiasis, mouth ulcers and gingivitis are common conditions which in some patients may suggest immunodeficiency or autoimmune conditions. Frequent causes of these conditions are listed in Table 4.4.

Allergy in dental practice

Introduction

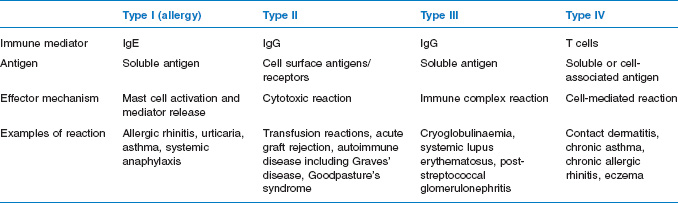

Hypersensitivity reactions are immune-mediated antigen-specific reactions that are either inappropriate or excessive and result in harm to the host; they have been classified by Gell and Coombs (see Table 4.5). The term allergy is most frequently equated with type I hypersensitivity reactions that are mediated via IgE, but is sometimes used in the context of type IV reactions. Allergic reactions, which can be severe and life threatening, can occur in dental practice, and knowledge of how to manage these conditions is therefore essential.

Table 4.4 Frequent causes of oral candida, mouth ulcers and gingivitis

| Frequent causes of oral candida |

|

| Frequent causes of mouth ulcers |

|

| Causes of gingivitis and tooth loss |

|

Table 4.5 Gell and Coombs classification of hypersensitivity reactions

Incidence of allergic disease

The incidence of allergic disease in western societies is increasing. More patients present with symptoms of rhinitis and conjunctivitis, symptoms of food allergy, eczema and asthma. It is hypothesised that the increase in allergic disease may be due in part to the decrease in infections encountered in the western world and the result of immunisation regimens that have protected us from other serious infections. Our environment has also altered substantially, with changes particularly in housing that have led to increased exposure to house dust mites. The proposed hygiene hypothesis suggests that because of the reduced exposure of the immune system to pathogens, especially at mucosal sites (gut, lungs, etc.), there is a switch of the immune system towards responses that allow the development of allergic conditions.

Allergens and irritants in dental practice

Many materials are used in dental practice that are considered to be potential allergens or irritants (see Table 4.6). Patients who feel they have a problem with these agents may present with a number of complaints including stomatitis, mouth ulceration, soreness in the mouth from oral lichenoid lesions, burning or tingling in the mouth, cheilitis or lip swelling, oral swelling, facial eruption or more systemic features of urticaria, wheezing, and even anaphylaxis.

Type I hypersensitivity (allergy)

Pathogenesis

On contact with the allergen, binding of this to specific IgE on the surface of mast cells occurs. This results in the degranulation of the cells and release of pre-formed mediators including histamine, heparin, lysosomal enzymes and proteases. Generation of a second set of chemical mediators (including leukotrienes, prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and chemotactic and activating factors) also occurs and these are released into the local tissues about 4–8 hours later. These mediators result in a host of clinical features described below.

Table 4.6 Materials to be considered as potential allergens or irritants in dental practice

|

|

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses