4

Examination of the Head and Neck

A thorough examination of the head and neck is an essential component of the diagnostic process. Clinicians should be able to recognize normal variations and abnormalities. For maximum yield, the patient should be seated at eye level with the examiner. When an abnormality is noted, the following questions should be asked: (1) is the abnormality itself important, or is it an inconsequential finding; (2) could the abnormality be related to a potential intraoral finding; and (3) is the abnormality suggestive of an underlying systemic disorder?

Examine the Head and Face

Note the Position and Observe Movement of the Head at Rest

Tilting of the head may indicate an attempt to compensate for defective vision or hearing or to minimize discomfort in the neck. An exaggerated forward thrust of the head may be associated with an abnormality of the cervical vertebrae. Sudden, unexpected movements of the head with facial grimaces may simply be a habitual spasm. A to-and-fro bobbing of the head may be secondary to aortic insufficiency. A subtle but steady rhythmic tremor of the head may suggest Parkinson’s disease. Constant licking of the corners of the mouth or smacking of the tongue is suggestive of tardive dyskinesia, a condition associated with neuroleptic drug therapy.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a degenerative central nervous system (CNS) disorder, which may be either primary or secondary. Primary PD is characterized by degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and other brainstem dopaminergic cell groups. The loss of substantia nigra neurons results in depletion of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Secondary PD is associated with loss of, or interference with, the action of dopamine in the basal ganglia due to other degenerative CNS diseases, exogenous toxins, or drugs. It is estimated that at least half a million people in the United States suffer from PD. Most cases begin after the age of 50. Among individuals older than 65 years of age, reported estimates range from 1.5% to 3.0%. When PD begins at or before the age of 50, genetic factors appear to predominate. In late-onset PD, the triggers are primarily environmental.

Clinical Features

Regardless of its etiology, striatal dopamine deficiency leads to an impaired ability to control the smooth movement of skeletal muscle. The most common initial symptom is resting tremor of the hands. The classic “pill-rolling” motion of the fingers is often unilateral, usually decreases with voluntary movement, is absent during sleep, and may be exacerbated during emotional stress and fatigue. The hands, arms, and legs are affected in decreasing order of frequency. Other characteristic findings include rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability.

As PD progresses, the face becomes mask-like, the mouth remains open, and blinking is diminished. The patient may experience difficulty swallowing and tends to drool. Speech becomes slurred, monotonous, stuttering, and soft (hypophonia). Cognitive and emotional symptoms of PD include depression, memory impairment, and an inability to make executive decisions. Approximately 25% of patients with PD meet the criteria for dementia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PD is suggested by a unilateral hand tremor, infrequent blinking, lack of facial expression, decreased movement, impaired postural reflexes, and a characteristic gait. The strongest support for the diagnosis of PD is provided by a positive clinical response to carbidopa and levodopa.

Treatment

Treatment protocols focus on increasing dopamine availability in the CNS and/or inhibiting the effects of acetylcholine. Levodopa, combined with carbidopa, remains the most effective symptomatic treatment for PD. Dental management of the patient with PD requires an awareness and accommodation of its progressive nature, which leads to physical, cognitive, and behavioral changes.

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a potentially irreversible, involuntary hyperkinetic disorder. The etiology of TD is not completely understood. One hypothesis suggests the possibility of dopamine receptor supersensitivity, while another contends that it is due to gamma-aminobutyric acid insufficiency. Advancing age is the most consistently established risk factor for TD, and there appears to be a linear correlation between age and both the prevalence and the severity of TD. Some ethnic differences, with higher rates in African Americans and lower rates in Chinese and other Asian populations, have been reported. Patients with diabetes mellitus are at a greater risk for developing TD, as are alcohol or drug abusers.

Numerous drugs have been implicated in TD. Prolonged treatment with neuroleptics such as risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol increase dopamine metabolism, which in turn results in increased free radical production. It is postulated that free radicals and other toxic agents damage the basal ganglia. A type of delayed-onset TD has also been reported in patients taking dopamine antagonists (e.g., metoclopramide, prochlorperazine), L-dopa, and amphetamines. Other drugs reported to be associated with acute TD include anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine), oral contraceptives, chloroquine-based antimalarials, lithium, and tricyclic antidepressants. In patients taking these latter drugs, the symptoms of TD are reversible upon dose reduction or discontinuation of the offending drug.

Clinical Features

TD is characterized by rapid, jerky, writhing (twisting and turning), involuntary movements that most often affect the oro-facial region along with distorted tonicity of arm, leg, and trunk muscles. Involvement of the arm, leg, and trunk muscles occurs chiefly during walking. The movements are highly complex and appear to be well coordinated, but are senseless. Dyskinetic blinking is an early sign. Other movements commonly involve the orobuccal, lingual, and facial muscles, especially in older individuals. Puckering or pouting, lip smacking, chewing, jaw clenching or mouth opening, facial grimacing, and blowing are common features. As the condition progresses, writhing of the tongue is characterized by thrusting of the tongue out of the mouth as if “fly catching.” Repeated licking of the lips or pressing the tongue against the cheeks may produce an obvious bulge of the cheek.

The oro-facial musculature is involved in about 75% of affected patients. The limbs are involved in 50%, the trunk in up to 25%, and all three muscle groups are affected in about 10% of patients. The movements of TD typically fluctuate in intensity over time, increase with emotional arousal, decrease with relaxation, and disappear during sleep. A majority of patients with TD have a mild disorder and may be unaware of its presence. However, 5–10% of patients suffer significant impairment. Oro-facial movements may lead to difficulty in eating or retaining dentures. Weight loss or cachexia may develop.

Diagnosis

The characteristic dyskinetic movements and their occurrence following exposure to neuroleptic drugs should suggest the presumptive diagnosis and mandate a medical consultation. A diagnosis is established following a complete neuropsychiatric evaluation.

Treatment

The best chance to induce remission, or at the least to minimize the progression of TD, is to discontinue the offending neuroleptic drug. In moderate-to-severe TD, drug therapy to treat involuntary movements may be necessary.

Note the Color of the Face

Pallor may be seen in patients with anemia or edema, and as a transient phenomenon in association with vasopressor syncope. Cyanosis may be evident in patients who have a congenital heart defect, congestive heart failure, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Increased concentration of bilirubin in the blood leads to jaundice of the skin, sclera of the eyes, and mucous membranes. It may be indicative of excessive red blood cell destruction, hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepato-cellular carcinoma, cholelithiasis, or pancreatic cancer. Port-wine nevi, or capillary or cavernous malformations affecting the cutaneous/mucosal distribution of the trigeminal nerve, may represent a manifestation of Sturge-Weber angiomatosis or Klippel-Trenauny syndrome. Deep bronzing of the face may be associated with Addison’s disease.

Pallor

Pallor refers to the abnormally pale appearance of the skin and/or mucous membranes and is a principal sign of anemia. Anemia reflects a reduction in the oxygen in blood due to an abnormality in the quantity or quality of red blood cells and is characterized by a reduction in hemoglobin concentration and the volume of erythrocytes in a unit volume of whole blood (hematocrit). Anemia may be due to (1) defective proliferation of red blood cells, (2) defective maturation of red blood cells, (3) increased destruction of red blood cells, or (4) acute or chronic blood loss.

Edema of the skin may also produce pallor. The structural elements of the integument are rendered more distant from each other as they are separated by fluid. Light penetrating the skin meets a diminished quantity of pigment, more rays are reflected, and the skin appears paler than normal.

A common cause of transient pallor is vasodepressor syncope due to the dilatation of resistance vessels. This form of fainting is likely to occur in the oral healthcare setting in response to sudden emotional stress brought on by pain, surgical manipulation, sight of blood, or heat. Cerebral blood flow becomes significantly reduced, precipitated by a generalized, progressive, autonomic (adrenergic followed by compensatory cholinergic) discharge.

Clinical Features

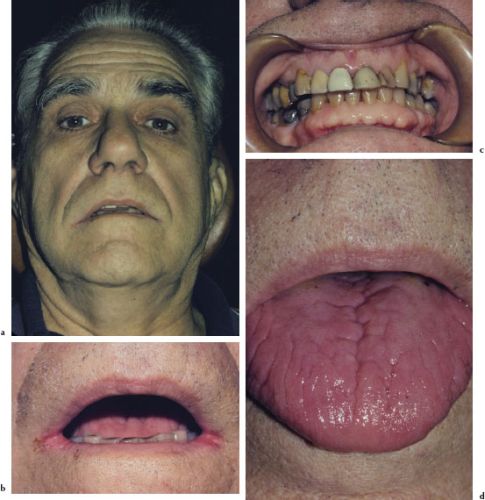

Pallor is a physical sign. While there is a wide variability in skin color among individuals due to the size of capillaries and their depth below the skin surface, the clinical appearance of the conjunctivae, lips, and oral mucosae, which demonstrate less of a variation in color, provide a more reliable indication of pallor (Figures 4.1a–4.1d). Similarly, the color of the nail bed and a well-delineated lunula are also good indicators of pallor.

Figures 4.1a–b. Pallor.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pallor is based on a careful inspection of the skin, conjunctivae, lips, oral mucosae, and nail beds. Establishing the etiology of persistent pallor is the responsibility of the patient’s physician.

Treatment

An appreciation for the extent and duration of pallor, along with any associated symptoms, may lead to the establishment of a specific etiology followed by appropriate treatment that will correct both the clinical signs and the underlying cause.

Cyanosis

Cyanosis is a physical finding characterized by a bluish discoloration due to an excess amount of reduced hemoglobin in the sub-papillary venous plexus. It may be peripheral or central. Peripheral cyanosis may be seen following exposure to low ambient temperatures, anxiety-induced vasoconstriction, Raynaud’s disease–associated vasospasm, other obstructive peripheral vascular abnormalities, and low cardiac output. Central cyanosis results from arterial hypoxemia and may result from serious cardiac and/or pulmonary abnormalities.

Clinical Features

Peripheral cyanosis tends to affect the upper and/or lower extremities, particularly the palms of the hands, the soles of the feet, and the nail beds. When cyanosis is caused by heart or lung disease, in addition to the extremities, it affects the “central” parts of the body, that is, the torso, face, lips, and oral mucosae (Figures 4.2a and 4.2b).

Diagnosis

Cyanosis is best recognized under natural, bright daylight in regions where the skin is thick, unpigmented, and flushed, such as the ear lobes, cutaneous surfaces of the lips, and the nail beds. Cyanosis is less apparent in the oral mucosae of patients with light complexion when compared to patients with dark skin. Overall, the visual perception of “blueness” varies greatly among clinicians and it is believed that most clinicians do not perceive cyanosis until the oxygen saturation has fallen to less than 80%.

Figures 4.2a and b. Cyanosis.

Treatment

A careful history and physical examination by a physician are warranted to determine the specific etiology and, consequently, the most appropriate treatment.

Jaundice

Jaundice is the result of increased concentrations of bilirubin in blood. Red blood cells, when destroyed, release hemoglobin, and bilirubin is a by-product of subsequent hemoglobin catabolism. The bilirubin molecule is attached to albumin and is conjugated with glucuronic acid in the liver, rendering it water-soluble. Conjugated bilirubin becomes a constituent of the bile and is transported to the duodenum where it gives the fecal matter its characteristic color. The predominance of conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin can pinpoint the metabolic problem as prehepatic (destruction of red blood cells), hepatic (acute viral, drug-induced, or alcoholic hepatitis; subacute or chronic hepatitis; cirrhosis; hepatocellular carcinoma), or posthepatic (biliary tract obstruction by duct stones, duct stricture, or pancreatic cancer).

Clinical Features

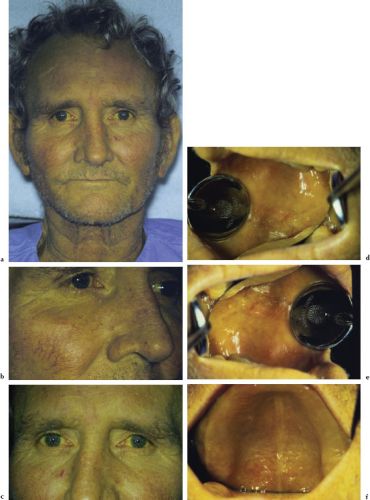

Jaundice is a sign that typically affects the skin, oral mucosae, and sclera of the eyes (Figures 4.3a–4.3f). When associated with vascular spiders of the face, it may suggest acute or chronic hepatitis. Vascular spiders seldom occur in patients with jaundice resulting from obstruction secondary to bile duct stones or neoplasia.

Figures 4.3a–f. Jaundice.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on visual inspection. While the skin is easily observed, the peripheral portion of the conjunctivae and the oral mucosae represent highly sensitive areas that may manifest jaundice before the skin. Medical consultation for further evaluation is warranted.

Treatment

The treatment of jaundice falls under the purview of the physician and is targeted at removing or controlling the underlying cause.

Port-Wine Nevi

A port-wine nevus is a characteristic form of a capillary hemangioma affecting the head and neck. While it often occurs as an isolated entity, its presence may be indicative of a more serious condition such as Sturge-Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome.

Clinical Features

Port-wine nevi are purplish, diffuse macules with irregular borders that are sharply demarcated from the adjacent normal skin. They occur unilaterally on the face and follow the first, second, third, or all three divisions of the trigeminal nerve (Figures 4.4a–4.4e).

Diagnosis

Port-wine nevi are easily diagnosed based on their characteristic appearance and history. A differential diagnosis should include Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (Table 4.1).

Treatment

Isolated port-wine nevi rarely require treatment and often involute during puberty. No consistently effective treatment is available to remove a port-wine nevus. Laser therapy may improve the cosmetic appearance of some lesions, but the improvement may only be temporary.

Table 4.1. Syndromes associated with port-wine nevi.

| Sturge-Weber syndrome | Klippel-Ternaunay syndrome |

| Port-wine nevus | Port-wine nevus |

| Seizures | Venous malformation (varicosities) |

| Mental impairment | Bony and soft tissue hypertrophy |

| “Tramline” calcifications of the cerebral cortex |

Figures 4.4a–e. Port-wine nevi.

Deep Bronzing: Addison’s Disease

Addison’s disease (AD) is a potentially life-threatening endocrine disorder characterized by chronic adrenocortical hypofunction. The resultant lack of cortisol impairs the patient’s ability to respond to physiologic stress. The cause of AD may be primary, secondary, or tertiary. Most cases of primary AD are caused by a gradual autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex. Less frequent causes of primary AD include glandular destruction by tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, histoplasmosis, primary or metastatic malignancies, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and drugs.

The incidence of primary AD in the general population is about 1/100,000. Secondary AD results from deficient adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, usually due to the presence or treatment of a pituitary or hypothalamic tumor. Tertiary AD is the most frequently observed type and develops as a consequence of long-term high-dose therapeutic corticosteroid administration, which leads to suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

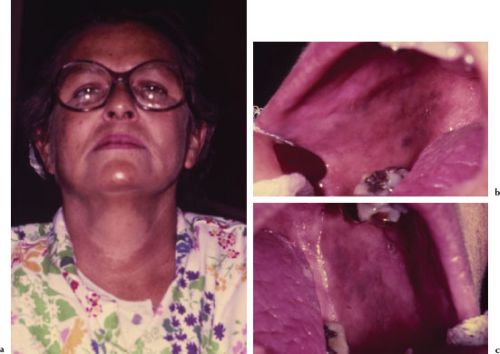

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations of AD include fatigue, weakness, listlessness, orthostatic hypotension, weight loss, and anorexia. Patients may also report a craving for salt and experience periods of hypoglycemia. The distinguishing sign of AD is hyperpigmentation, or bronzing, most evident on sun-exposed areas of the skin, and patchy brown pigmentation of the buccal mucosae, tongue, and less frequently the lips and gingivae (Figures 4.5a–4.5c). The cause of these pigmentations is thought to be an increased compensatory pituitary synthesis of ACTH and melanin-stimulating hormone (MSH).

Figures 4.5a–c. Addison disease.

Diagnosis

The suspicion of AD is based on the presenting clinical signs and symptoms. Medical referral for further evaluation is warranted. Both passive (e.g., serum cortisol and ACTH levels) and provocative (e.g., insulin tolerance test) laboratory testing, combined with appropriate imaging tests, are required to establish the specific diagnosis.

Treatment

Both primary and secondary adrenocortical hypofunction require life-long glucocorticoid, and if necessary, mineralocorticoid replacement therapy. Therapy is empirically individualized to maintain normal weight and sense of well-being. Commonly prescribed glucocorticoid agents include hydrocortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone. The chosen agent is often administered in the morning and evening to mimic the normal diurnal release of these hormones.

The impaired ability to respond to excess physiologic stress places a patient with AD at risk for developing an Addisonian crisis. During an Addisonian crisis, the patient becomes dangerously hypotensive and experiences hypoglycemia. Precipitating factors may include stress, infection, trauma, surgery, and the use of general anesthesia. Treatment of an Addisonian crisis is a medical emergency and includes prompt intravenous administration of saline and a glucocorticoid.

Observe Facial Characteristics

A massive face, craggy eyebrows, prominent nose, enlarged mandible, and macroglossia are characteristic of acromegaly. A puffy edematous face; dry, coarse, and scaly skin; and slowed speech and mentation are characteristic signs of hypothyroidism. A moon facies (fat deposition in the face), hirsutism, and acne may represent Cushing’s syndrome associated with excess corticosteroids either from an endogenous or an exogenous source. Bell’s palsy, characterized by unilateral paralysis of the facial muscles, may reflect transient or permanent seventh nerve damage.

Acromegaly

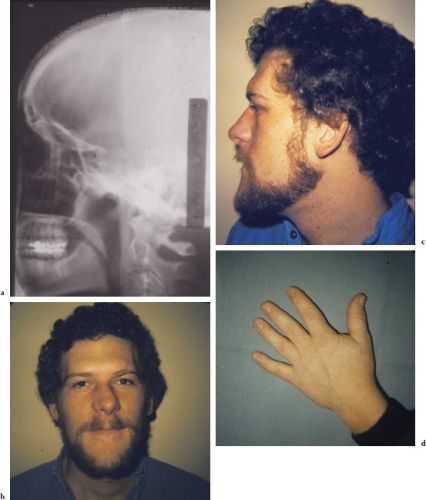

Acromegaly results from an overproduction of growth hormone after closure of the epiphyseal plates, and is usually due to an adenoma of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland (Figure 4.6a). It is a rare condition with a prevalence of approximately 50–70 cases per million and an incidence of 3 cases per million per year. Acromegaly progresses slowly and insidiously and is most often diagnosed during the fourth decade of life, typically 10 years after initial onset.

Clinical Features

Clinical signs and symptoms include hyper-hidrosis, muscle weakness, paresthesia, sleep apnea, hypertension, and heart disease. Skeletal growth can lead to prognathism, frontal bossing, nasal bone hypertrophy, and large hands and feet; coarsening of facial features, prominent lips, and macroglossia are common (Figures 4.6b–4.6g). An anterior open bite reflects supereruption of posterior and flaring of anterior teeth.

Diagnosis

The characteristic clinical presentation of acromegaly should alert the clinician and prompt a medical referral. Reviewing previous photographs of a patient may help to confirm clinical impression. Laboratory testing to establish the presence of elevated levels of growth hormone (GH) confirms the diagnosis. Radiographic imaging often reveals ballooning of the sella turcica, an indicator of pituitary enlargement. Other potential head and neck radiographic findings include enlargement of the paranasal sinuses, thickening of the outer table of the skull, increased condylar growth, and hypercementosis.

Figures 4.6a–g. Acromegaly.

Treatment

Measures to abolish or obtund excess GH production include microsurgery, radiation therapy, and medical therapy combined with routine follow-up examinations. The skeletal and to some degree soft-tissue changes are permanent.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is the most common form of thyroid dysfunction encountered in medical practice. If the condition occurs in infants and young children, it leads to cretinism. In adults it causes myxedema. Approximately 95% of patients with hypothyroidism have primary thyroid disease. Primary hypothyroidism may result from diseases or therapy that destroy thyroid tissue and include Hashimoto thyroiditis, radioactive iodine therapy for Graves’ disease, subtotal thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease or nodular goiter, deficient or excessive iodine intake, or subacute thyroiditis. Secondary hypothyroidism is due to inadequate production of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) by the pituitary gland. Other infrequent causes of hypothyroidism include radiation to the neck, postpartum thyroiditis, and exposure to drugs such as iodine, lithium, and amiodarone.

Clinical Features

The thyroid gland may be normal, nonpal-pable, or diffusely enlarged. The classic features of hypothyroidism include sinus bradycardia, hoarseness, nonpitting edema (myxedema) of the skin, periorbital edema, dryness of the skin, brittleness of the scalp hair, and an enlarged tongue and mouth breathing (Figure 4.7). Other signs and symptoms such as lethargy, depression, memory loss, cognitive impairment, modest weight gain, intolerance to cold, constipation, and neuromuscular dysfunction (vague aches and pains) are common.

Figure 4.7. Hypothyroidism.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic workup for a patient suspected of having hypothyroidism should include a thorough historical, clinical, and laboratory assessment. The laboratory hallmark of primary hypothyroidism is an increased compensatory serum TSH concentration and elevated cholesterol.

Treatment

The treatment of hypothyroidism involves lifelong thyroid hormone replacement, most commonly with levothyroxine. Once euthyroid state is attained, follow-up at regular intervals is recommended to avoid over-treatment (iatrogenic hyperthyroidism). Mild to moderate hypothyroidism is not a contraindication to dental care; patients with severe hypothyroidism have an impaired ability to respond to physiologic stress and may experience myxedema come. Patients with hypothyroidism, to a variable degree, are hyperreactive to CNS depressants.

Cushing’s Syndrome

Chronic glucocorticoid excess leads to the development of Cushing’s syndrome. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) synthesized in the hypothalamus stimulates pituitary ACTHf secretion. ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to release cortisol. Cortisol, the body’s main glucocorticoid, exerts a negative feedback to help modulate further CRH and ACTH secretion. The pathogenic mechanisms of Cushing’s syndrome can be divided into those that are ACTH-dependent and those that are ACTH-independent. A pituitary adenoma represents the most common type of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome and accounts for 60–80% of all cases. The most common form of ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome is due to adrenal hyperplasia. The estimated annual incidence of a pituitary adenoma is in the range of 0.1–1 new cases per 100,000.

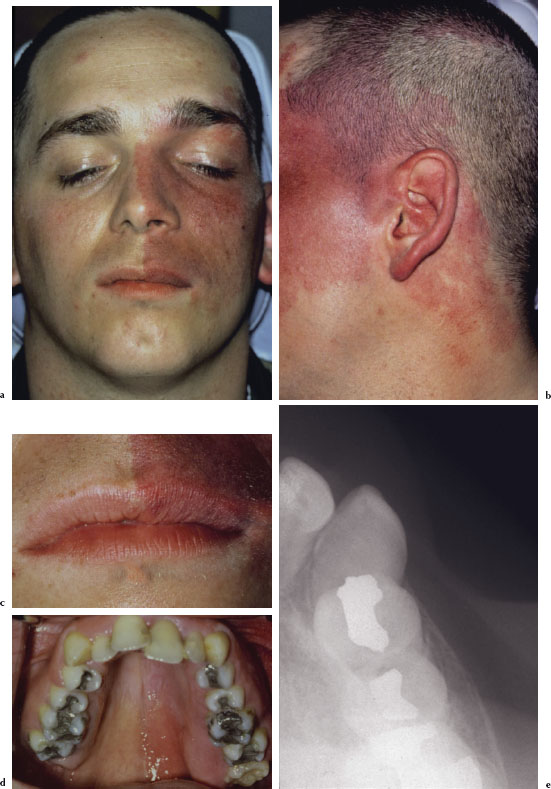

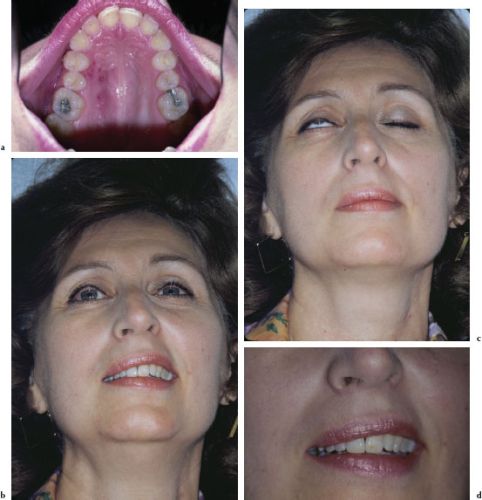

Clinical Features

The clinical signs and symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome include truncal obesity, glucose intolerance, muscle weakness, hypertension, osteoporosis, easy bruising, and edema (Figure 4.8a). Head and neck and oral manifestations of Cushing’s syndrome include red cheeks, moon face, hirsutism, acne, and retarded dental age (Figures 4.8b and 4.8c).

Diagnosis

Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome should be referred for medical evaluation. The most common test for screening for Cushing’s syndrome is a 24-hour urine collection with analysis for urinary free cortisol excretion. More specific tests include the dexamethasone suppression test, ACTH assay, and CRH stimulation test. Imaging techniques (CT, MRI) are useful to localize pituitary or ectopic ACTH-producing tumors and adrenal masses.

Figures 4.8a–c Cushing’s syndrome.

Treatment

Surgical treatment, depending on the etiology, may include trans-sphenoidal selective pituitary adenomectomy or bilateral adrenalectomy. Pituitary irradiation may be used in adult patients in whom a surgical approach is contraindicated. Depending on the extent of the therapeutic intervention, some patients will require lifelong hormonal replacement therapy. During periods of extreme stress (e. g., infection, surgery, and trauma), patients on replacement glucocorticoid therapy may require supplemental glucocorticoid administration to prevent adrenal insufficiency. Because of an increased susceptibility to infection and possible delayed wound healing, the postoperative status of surgical patients should be monitored closely.

Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s palsy (BP) is a common, acute, neurological disorder characterized by the sudden onset of facial nerve (C.N. VII) paralysis. The average annual incidence of BP is 13–34 patients per 100,000. It is more common in those aged 15–45 years, with the peak incidence in the third decade of life. The right and left sides are affected equally, and there is no gender predominance. Bilateral facial palsy is rare, with a frequency of less than 1%.

Proposed etiologies for BP include infectious, neoplastic, traumatic, and idiopathic causes. Edema and subsequent nerve entrapment of the facial nerve secondary to infection remains one of the most plausible causes. While BP is frequently attributed to a viral cause, no specific virus has been consistently demonstrated. Those most frequently implicated include herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (Figure 4.9a), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), influenza type B virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus, mumps, coxsackie virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and HIV.

Clinical Features

The onset of BP is usually acute and peaks after a few days. The affected side of the face lacks expression during normal conversation. The inability to close the eyes places the patient at risk for corneal/conjunctival dryness and ulceration. The eyeball may be turned upward in an attempt to block entering light; other common findings include an inability to whistle, smile, or grimace (Figures 4.9b–4.9d). Hypersensitivity to sound (hyperacusis), loss of taste (ageusia), and pain near the mastoid area may also be present.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BP is relatively straightforward. However, a careful clinical history must be obtained to rule out other forms of facial nerve dysfunction such as trauma, otologic disease, and intracranial mass. A thorough examination of the head and cervical spine, including cranial nerve testing (i.e., eye closure, elevation of the eyebrows, smiling, frowning, and pursing of the lips) should be performed. Evidence of involvement of other cranial nerves should alert the clinician to consider other causes.

Treatment

The management of BP often requires a multidisciplinary approach. Eighty-three percent of all patients experience resolution with nothing more than supportive therapy. Recovery typically begins within 2 weeks but may take up to 6 months to complete. However, 17% of patients experience incomplete recovery and manifest moderate to severe residual impairment. The risk of incomplete recovery is increased by a multitude of factors including initial disease severity, older age (> 60 years), delayed onset of recovery (> 3 weeks), pregnancy, and the presence of other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and herpes zoster infection.

Supportive treatment includes a temporary patch to protect the exposed eye, ocular antibiotics and artificial tears to prevent corneal ulceration, and physical therapy to prevent contracture of the paralyzed muscles. Evidence for or against targeted drug therapy remains controversial, and further study is necessary. However, in a recent review, the use of a combination regimen of acyclovir and prednisone appeared to improve overall outcome, if commenced within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms.

Figures 4.9a–d. Bell’s palsy.

Note Facial Architecture

Facial asymmetry may be caused by a neurofibroma, an intramuscular hemangioma, a lymphangioma, fibrous dysplasia, progressive hemifacial atrophy, an osteosarcoma, a chondrosarcoma, or by rare genetic disorders such as focal dermal hypoplasia. Subcutaneous emphysema may present as an acute, spontaneous form of facial asymmetry. A pronounced enlargement of the cranial vault is characteristic of Paget’s disease. Multiple sebaceous or dermoid cysts and osteomas involving the skull may indicate Gardner’s syndrome.

Neurofibroma

A neurofibroma is a benign tumor derived from the nerve sheath and is composed of a proliferation of Schwann cells, perineural fibroblasts, and axons intermixed with mast cells. Most are discovered in adulthood and there is no gender predilection.

Figures 4.10a–c. Neurofibroma.

Clinical Features

Some neurofibromas are discrete and well circumscribed, whereas others are diffuse and infiltrating. Neurofibromas are commonly found on the skin. Intraorally, neurofibromas are most commonly found in the tongue, buccal mucosa, and lips; less commonly they may affect the alveolar bone (Figures 4.10a–4.10c). Neurofibromas arising in the tongue tend to be diffuse, while those arising in other locations tend to present as relatively well-demarcated, freely moveable, submucosal nodules. Depending on the degree of collagenization, neurofibromas may be soft or firm on palpation. Intraosseous neurofibromas typically present as a swelling without pain or parasthesia. Radiographically, the intraosseous neurofibroma is relatively well demarcated, radiolucent, and may be either unilocular or multilocular. Root divergence may be evident.

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of a neurofibroma is established by biopsy. The presence of more than two neurofibromas and six or more café-au-lait cutaneous macules should prompt the practitioner to consider the possibility of neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen’s disease of the skin). It is a hereditary neurological disorder with an incidence of about 1 per 3,000. No racial or sex predilection is noted. Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 are at an increased risk for developing cognitive deficits, epilepsy, and malignant nerve sheath tumors.

Treatment

There is no cure for neurofibromatosis. Treatment consists of routine monitoring and surgery when required to remove painful or disfiguring tumors. While the overall prognosis is good, malignant transformation of tumors occurs in 3–5% of the cases.

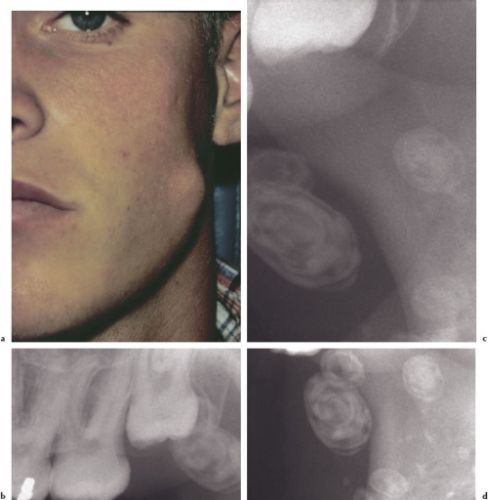

Intramuscular Hemangioma

Intramuscular hemangiomas (IMHs) are benign congenital neoplasms believed to evolve from an abnormally differentiated endothelial primordial network. This network is characterized by endothelial hyperplasia and malformations that enlarge by rapid cellular proliferation during the neonatal period, followed by a slow involution phase. Intramuscular hemangiomas account for less than 1% of all hemangiomas, of which approximately 15% occur in the head and neck area.

Clinical Features

In the head and neck area, the masseter muscle represents the most common site (36%) for an IMH, followed by the trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, periorbital, and temporalis muscles. Intramuscular hemangiomas are usually asymptomatic until a growth spurt begins in the second or third decades of life, at which time pain occurs in about 50% of the cases. A palpable, fluctuant, or firm mass is present in up to 98% of the cases (Figure 4.11a). The size of an intramasseter hemangioma may increase with sustained masticatory pressure (clinching of teeth) and decrease subsequent to relaxation of the masticatory muscles. Radiographically, the presence of soft-tissue calcifications or phleboliths (spherical lamellar structures with irregular radiopaque and radiolucent areas) is seen in more than 15% of cases (Figures 4.11b–4.11d). Phleboliths are “stones” that appear to form within benign vascular lesions (hemangiomas, vascular malformations) secondary to a thrombotic episode.

Diagnosis

Sonography is the first-line imaging procedure for patients with soft-tissue swellings. Magnetic resonance imaging may be more reliable in detecting and delineating deeply situated and large IMHs. Angiography is diagnostic in most cases. The finding of a phlebolith is pathognomonic for a benign hemangioma. In many cases, a biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Management of IMHs should be individualized according to the size and anatomic accessibility of the tumor, rate of growth, age of the patient, and cosmetic and functional considerations. If indicated, complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Local recurrence has been reported in about 18% of the cases.

Figures 4.11a–d. IM hemangioma.

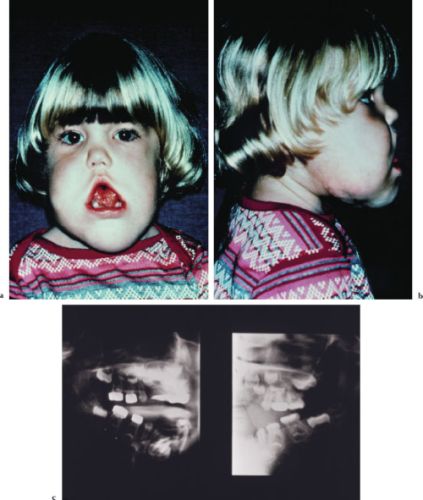

Lymphangioma

Lymphangiomas are benign nonencapsulated tumors of lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphatic malformations are present at birth and 80% become clinically evident before 2 years of age. However, lymphangiomas have been known to suddenly manifest in older children, adolescents, and adults. There is no gender predilection.

Clinical Features

Intraoral lymphangiomas most commonly occur on the tongue but are also seen on the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. Superficial microcystic lesions are manifested as papillary lesions, which may be of the same color as the surrounding mucosa, or may be slightly erythematous. Deeper macrocystic lesions appear as diffuse nodules or masses without any significant change in surface texture or color. If the tongue is affected, considerable enlargement may occur. Facial lymphangiomas are the most common cause for enlarged lips (macrocheilia), enlarged ears (macrotia), and enlarged cheeks (macromala); cervicofacial lymphangiomas are associated with overgrowth of the mandibular body, which may lead to malocclusion (Figures 4.12a–4.12c).

Figures 4.12a–c. Lymphangioma.

Diagnosis

A lymphangioma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of all head and neck masses or swellings. Magnetic resonance imaging and a biopsy are often utilized to help confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice since a lymphangioma is radioresistant and insensitive to sclerosing agents. Spontaneous regression is rare and lesions tend to recur after removal.

Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental abnormality of bone characterized by replacement of normal bone with fibrous connective tissue and woven bone trabeculae. Fibrous dysplasia represents 2% of all bone abnormalities, and there are two recognized variants: monostotic (single bone) and polyostotic (multiple bones).

The monostotic form is more common and accounts for approximately 80% of cases. It occurs primarily during the second decade of life with 75% of patients younger than 30 years of age at the time of diagnosis. The male-female ratio is approximately equal, and the maxilla is more commonly involved than the mandible.

There are two recognized variants of the polyostotic form. The Jaffe-Lichtenstein type is associated with “café-au-lait” dermal pigmentations (macules). McCune-Albright syndrome/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses