Cysts and Tumors of Odontogenic Origin

Odontogenic Cysts

Cysts of the jaws can be classified as:

The following classification of odontogenic cysts (Table 4-1) is based on etiology and tissue of origin.

Table 4-1

Classiication of odontogenic cysts

Classification by etiology

Dentigerous cyst

Eruption cyst

Odontogenic keratocyst

Gingival cyst of newborn

Gingival cyst of adult

Lateral periodontal cyst

Calcifying odontogenic cyst

Glandular odontogenic cyst

Inflammatory:Result of inflammation

Periapical cyst

Residual cyst

Paradental cyst

Classification by tissue of origin

Derived from rests of Malassez

Periapical cyst

Residual cyst

Derived from reduced enamel epithelium

Dentigerous cystt

Eruption cyst

Derived from dental lamina (rests of Serres)

Odontogenic keratocyst

Gingival cyst of newborn

Gingival cyst of adult

Lateral periodontal cyst

Glandular odontogenic cyst

Unclassified

Paradental cyst

Calcifying odontogenic cyst

Dentigerous Cyst (Follicular cyst)

Clinical Features

This cyst is always associated initially with the crown of an impacted, embedded or unerupted tooth (Fig. 4-1). A dentigerous cyst may also be found enclosing a complex compound odontoma or involving a supernumerary tooth. The most common sites of this cyst are the mandibular and maxillary third molar and maxillary cuspid areas, since these are the most commonly impacted teeth. Most lesions present in second and third decades, with slight male predilection (M:F–3:2). Most dentigerous cysts are solitary. Bilateral and multiple cysts are usually found in association with a number of syndromes including cleidocranial dysplasia and Maroteaux–Lamy syndrome. In the absence of these syndromes, bilateral dentigerous cysts are rare. The dentigerous cyst is potentially capable of becoming an aggressive lesion. Expansion of bone with subsequent facial asymmetry, extreme displacement of teeth, severe root resorption of adjacent teeth and pain are all possible sequelae brought about by continued enlargement of the cyst. Cystic involvement of an unerupted mandibular third molar may result in a ‘hollowing-out’ of the entire ramus extending up to the coronoid process and condyle as well as in expansion of the cortical plate due to the pressure exerted by the lesion. Associated with this reaction may be displacement of the third molar to such an extent that it sometimes comes to lie compressed against the inferior border of the mandible. In the case of a cyst associated with a maxillary cuspid, expansion of the anterior maxilla often occurs and may superficially resemble an acute sinusitis or cellulitis. There is usually no pain or discomfort associated with the cyst unless it becomes secondarily infected.

Radiographic Features

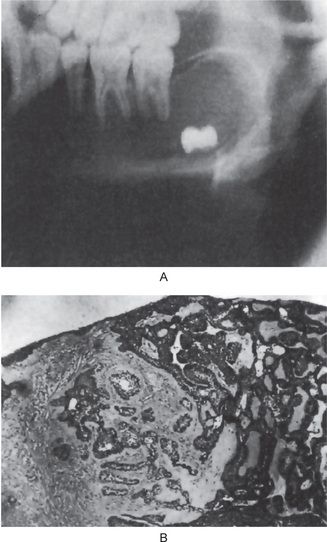

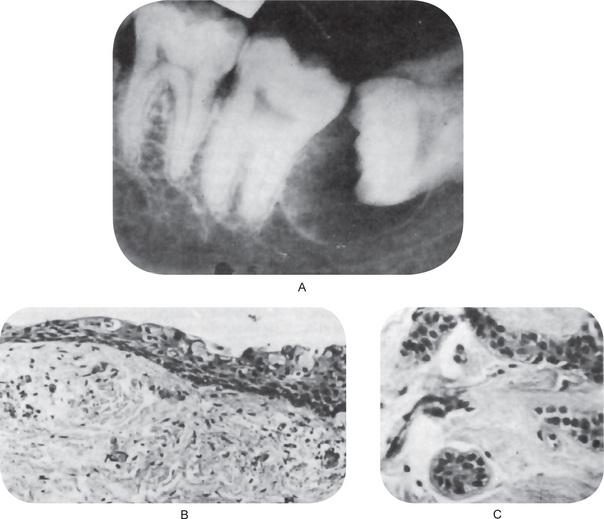

Radiographic examination of the jaw involved by a dentigerous cyst will reveal a radiolucent area associated in some fashion with an unerupted tooth crown (Fig. 4-2A). The impacted or otherwise unerupted tooth crown may be surrounded symmetrically by this radiolucency, although the distinction between a small dentigerous cyst and an enlarged dental follicle or follicular space is quite arbitrary, especially since the small cyst and the enlarged follicle would be histologically identical. While a normal follicular space is 3–4 mm, a dentigerous cyst can be suspected when the space is more than 5 mm. Only when the size of the radiolucency is grossly pathologic can the distinction be made with assurance.

Figure 4-2 Dentigerous cyst. The radiograph (A) demonstrates a large radiolucent area associated with the crown of the impacted mandibular third molar. The photomicrograph (B) shows this cyst to be lined by a thin layer of stratified squamous epithelium similar in appearance to the primordial cyst. Occasional mucuscontaining cells are present in the epithelium. Small islands of odontogenic epithelium (C) are often present in the connective tissue wall.

Histologic Features

There are no characteristic micro-scopic features which can be used reliably to distinguish the dentigerous cyst from the other types of odontogenic cysts. It is usually composed of a thin connective tissue wall with a thin layer of stratified squamous epithelium lining the lumen (Fig. 4-2B). Rete peg formation is generally absent except in cases that are secondarily infected. The connective tissue wall is frequently quite thickened and composed of a very loose fibrous connective tissue or of a sparsely collagenized myxomatous tissue, each of which has been sometimes mistakenly diagnosed as either an odontogenic fibroma or an odontogenic myxoma. A hyperplastic dental follicle is not necessarily associated with inflammation. An additional feature of the connective tissue wall of both normal dental follicles and dentigerous cysts is the presence of varying numbers of islands of odontogenic epithelium (Fig. 4-2C). These are sometimes very sparse and obviously inactive, while at other times they are present in sufficient numbers to be mistaken for an amelo-blastoma. While this latter odontogenic tumor can originate in this situation, care must be taken to differentiate between it and simply odontogenic epithelial rests. Inflammatory cell infiltration of the connective tissue is common although the cause for this is not always apparent. An additional finding, especially in cysts which exhibit inflammation, is the presence of Rushton bodies within the lining epithelium. These are peculiar linear, often curved, hyaline bodies with variable stainability which are of uncertain origin, questionable nature and unknown significance. Even electron microscopic studies, such as those of El-Labban, have only been of partial help in determining that the structures are probably of hematogenous origin, although it is not clear why they have such an intimate relationship to epithelium. The content of the cyst lumen is usually a thin, watery yellow fluid, occasionally blood tinged.

The pluripotentialities of the epithelium in mandibular dentigerous cysts has been further emphasized by Gorlin, who described mucus-secreting cells in the lining stratified squamous epithelium, respiratory epithelial lining, sebaceous cells in the connective tissue wall, and lymphoid follicles with germinal centers.

Potential Complications

• The development of an ameloblastoma either from the lining epithelium or from rests of odontogenic epithelium in the wall of the cyst.

• The development of epidermoid carcinoma from the same two sources of epithelium.

• The development of a mucoepidermoid carcinoma, basically a malignant salivary gland tumor, from the lining epithelium of the dentigerous cyst which contains mucussecreting cells, or at least cells with this potential, most commonly seen in dentigerous cysts associated with impacted mandibular third molars.

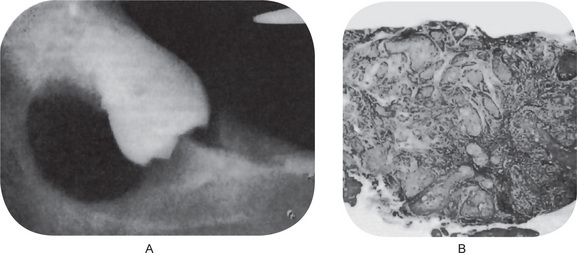

It is of great clinical significance that numerous cases of ameloblastoma have been reported developing in the wall of dentigerous cysts from the lining epithelium or associated epithelial rests (Fig. 4-3). Stanley and Diehl have reviewed a series of 641 cases of ameloblastoma and have found that at least 108 cases of this neoplasm, approximately 17%, were definitely associated with an impacted tooth and/or a follicular or dentigerous cyst. The disposition for neoplastic epithelial proliferation in the form of an ameloblastoma is far more pronounced in the dentigerous cyst than in the other odontogenic cysts. The formation of such a tumor manifests itself as a nodular thickening in the cyst wall, the mural ameloblastoma, but this is seldom obvious clinically. Therefore, it is not only good clinical practice, but also an absolute requisite that all tissue from dentigerous cysts be submitted to a qualified oral pathologist for thorough gross and microscopic examination. In reviewing the histologic changes sought by the oral pathologist which occur in the dentigerous cyst as a premonitory manifestation of ameloblastoma, Vickers and Gorlin have stressed that hyperchromatism of basal cell nuclei, palisading with polarization of basal cells and cytoplasmic vacuolization with intercellular spacing of the lining epithelium, when observed together, are manifestations of impending neoplasia. These findings may occur individually in other rather harmless conditions. The presence of sprouting or budding and protruding of epithelial islands from lining epithelium has been claimed to be evidence of neoplastic transformation, but this in itself was not considered such an indication by Vickers and Gorlin.

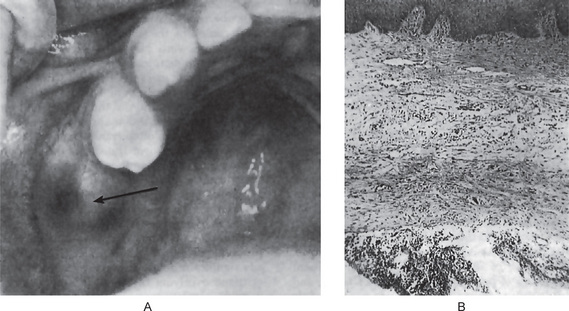

The development of epidermoid carcinoma from the lining epithelium of the dentigerous cyst also has been adequately documented in the literature reviewed by Gardner, who reported eight acceptable cases among 25 cases of carcinoma developing in odontogenic cysts of all types combined. Browne and Gough have reported two additional cases of malignant transformation in dental cysts and suggested that keratin metaplasia in long-standing cyst lining appears to precede the development of the carcinomatous change, although there is little evidence that the odontogenic keratocyst is associated with malignant change more commonly than other types of odontogenic cysts. The predisposing factor and mechanism of development of this malignancy are unknown, but its occurrence appears unequivocal (Fig. 4-4).

Finally, the development of a mucoepidermoid carcinoma, a type of salivary gland tumor, is less well documented than the epidermoid carcinoma of this origin, but it also appears to be a potentiality. The inclusion of normal salivary gland tissue in the posterior portion of the body of the mandible has been reported, and undoubtedly, some central salivary gland tumors in this location originate from this source. However, cases of central mucoepidermoid carcinoma (q.v.) have been discovered in association with dentigerous cysts involving impacted mandibular third molars, and considering the frequency with which mucus-secreting cells are found in this lining epithelium indicative of the pluripotentiality of this epithelium, this very distinct possibility must always be considered. These findings comprise most of the medical rationale for removal of impacted third molars with pericoronal radiolucencies; however, impacted teeth with small pericoronal radiolucencies (suggesting the presence of normal dental follicle rather than dentigerous cyst) also may be monitored with serial radiographic examination. Any increase in the size of the lesion should prompt removal and histopathologic examination. Any lesion that appears larger than a normal dental follicle indicates removal and histopathologic examination.

Eruption Cyst

An eruption cyst or ‘eruption hematoma’ is in fact a dentigerous cyst occurring in the soft tissues (Shear, 1992). Whereas the dentigerous cyst develops around the crown of an unerupted tooth lying in the bone, the eruption cyst occurs when a tooth is impeded in its eruption within the soft tissue overlying the bone. The pathogenesis is probably very similar to that of the dentigerous cyst. The difference is that the tooth in the case of the eruption cyst is impeded in the soft tissue of gingiva rather than in the bone. The presence of particularly dense fibrous tissue in the overlying gingiva could be responsible.

Clinical Features

Shear (1992) had recorded a 0.8% frequency. It is likely that they occur more frequent clinically and as some rupture spontaneously, these cysts go unnoticed and are not submitted for histological examination.

Histologic Features

In noninflamed areas, the epithelial lining of the cysts is characteristically of reduced enamel epithelial origin, consisting of two or three cell layers of squamous epithelium with a few foci where it may be a little thicker. The adjacent corium is hyperemic and is the seat of a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (Fig. 4-5).

Odontogenic Keratocyst

This is the most interesting of jaw cysts. The term ‘odontogenic keratocyst’ was first used by Philipsen in 1956, while Pindborg and Hansen in 1963 described the essential features of this type of cyst. It is named keratocyst because the cyst epithelium produces so much keratin that it fills the cyst lumen. Furthermore, flattening of the basement membrane and palisading of the basal epithelial cells, reminiscent of odontogenic epithelium, are characteristics of odontogenic keratocyst.

They are unique odontogenic lesions that have the potential to behave aggressively, that can recur, and can be associated with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Toller (1967) suggested that OKCs might be regarded as benign cystic neoplasms. Whether they are developmental or neoplastic continues to be debated.

Differences in cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) immunoreactivity between the parakeratinized OKC and the orthokeratinized variety have been demonstrated and the suggestion made that the latter having a considerably less aggressive behavior is different entity and should bear a different name orthoke-ratinized odontogenic cyst (Shear M, 2002).

Reclassification of the Odontogenic Keratocyst to Tumor: Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor (KOT)

• Behavior: The KOT is locally destructive and recurrence rate is very high.

• Histopathology: The basal epithelial layer of KOT shows proliferation and budding into the underlying connective tissue in the form of daughter cysts and mitotic figures are frequently found in the suprabasal layers of the lesional epithelium.

• Genetics: PTCH (patched), a tumor suppressor gene involved in both syndrome associated and sporadic KOTs, occurs on chromosome 9q22.3 – q31. Normally, PTCH forms a receptor complex with the oncogene SMO (smoothened) for the SHH (sonic hedgehog) ligand. PTCH binding to SMO inhibits growth signal transduction. SHH binding to PTCH releases this inhibition. If normal functioning of PTCH is lost, the proliferation-stimulation effects of SMO are permitted to predominate.

Evidence has shown that the pathogenesis of syndrome associated and sporadic KOTs involves a ‘two hit mechanism’, with allelic loss at 9q22. The ‘two hit mechanism’ refers to the process by which a tumor suppressor gene is inactivated. The first hit is a mutation in one allele, which, although it can be dominantly inherited, has no phenotypic effect. The second hit refers to loss of the other allele and is known as ‘loss of heterozygosity’ (LOH). In KOTs, this leads to the dysregulation of the oncoproteins cyclin D1 and p53. LOH in the 9q22.3–q31 region has been reported for many epithelial tumors, including basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and transitional cell carcinomas; and LOH is by definition a feature of tumorigenic tissue.

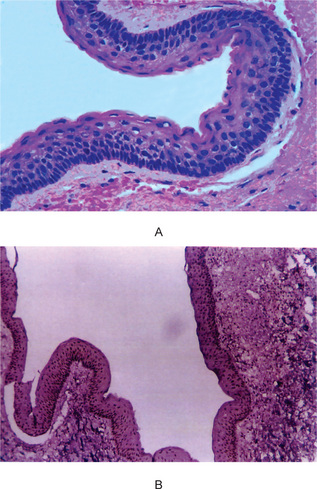

Histologic Features

• A parakeratinized surface which is typically corrugated, rippled or wrinkled.

• A remarkable uniformity of thickness of the epithelium, usually ranging from 6 to 10 cells thick.

• A prominent palisaded, polarized basal layer of cells often described as having a ‘picket fence’ or ‘tombstone’ appearance.

The lumen of the keratocyst may be filled with a thin straw colored fluid or with a thicker creamy material. Sometimes the lumen contains a great deal of keratin, while at other times it has little. Cholesterol, as well as hyaline bodies at the sites of inflammation, may also be present. The electrophoretic measurement of fluid from these cysts has been reported by Toller to show that it contains a very low content of soluble protein compared with the patient’s own serum (Fig. 4-6).

Dysplastic and neoplastic transformation of the lining epithelium in the odontogenic keratocyst is an uncommon occurrence but has been reported. Of the 312 keratocysts studied by Brannon, only two exhibited cellular atypia. Occasional other cases have also been described in the literature. Areen and his associates have recently reported a case of epidermoid carcinoma developing in an odontogenic keratocyst, and in reviewing the literature, have emphasized the necessity for careful microscopic examination of all such cysts.

Finally, the highly characteristic nature of the parakeratinized lining epithelium and its relationship to the high recurrence rate have been emphasized by a report dealing with orthokeratinized odontogenic cysts and their recurrence rate. Wright investigated 59 cases of orthokeratinized odontogenic cysts and found that they showed a predilection for occurrence in males, most commonly in the second to fifth decades. These cysts were located predominantly in the posterior mandible, where they most typically appeared as dentigerous cysts. The thin, uniform lining epithelium was covered with orthokeratin and showed a prominent granular layer and a cuboidal to flattened basal layer. Follow-up of 24 of these patients revealed only one case of recurrence. This difference in biologic behavior would further underscore the necessity for very strict application of the definition of the term odontogenic keratocyst in diagnosis of the lesion (Fig. 4-7).

Figure 4-7 Odontogenic keratocyst. (A) The epithelial lining is uniformly thin, generally ranging from 8–10 cell layers thick. The basal layer exhibits a characteristic palisaded pattern with polarized and intensely stained nuclei of uniform diameter. The luminal epithelial cells are parakeratinized and produce an uneven or corrugated profile. (B) Odontogenic keratocyst stained using proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibodies (x 10).

Treatment and Prognosis

The most important feature of the odontogenic keratocyst is its extraordinary recurrence rate. This has been reported as being between 13 and 60%. A review of 763 cases of odontogenic keratocysts in 13 different reported series of cases has shown the average recurrence rate to be 26%, with the majority occurring within five years of the surgical procedure. Forssell, Forssell and Kahnberg (1988) observed that recurrences were more frequent (63%) with cysts in patients with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome than with cysts in patients without the syndrome (37%). Keratocysts enucleated in one piece recurred significantly less often than cysts enucleated in several pieces, and the recurrence rate in cases with a clinically observable infection, a fistula or with a perforated bony wall was higher. The size of the cyst did not seem to influence its prognosis after surgery, but those whose radiographic appearance was multilocular had a higher recurrence rate than those with a unilocular appearance.

Jaw Cyst-Basal Cell Nevus, Biid Rib Syndrome (Basal cell nevus syndrome, hereditary cutaneomandibular polyoncosis, Gorlin and Goltz syndrome)

Clinical Features

• Cutaneous anomalies, including basal cell carcinoma, other benign dermal cysts and tumors, palmar pitting, palmar and plantar keratosis and dermal calcinosis.

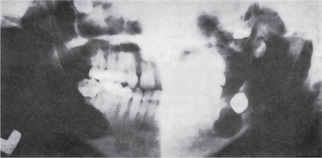

• Dental and osseous anomalies, including odontogenic keratocysts (often multiple), mild mandibular progna-thism, rib anomalies (often bifid), vertebral anomalies and brachymetacarpalism (Fig. 4-8).

• Ophthalmologic abnormalities, including hyper-telorism with wide nasal bridge, dystopia canthorum, congenital blindness and internal strabismus.

• Neurologic anomalies, including mental retardation, dural calcification, agenesis of corpus callosum, congenital hydrocephalus and occurrence of medulloblastomas with greater than normal frequency.

• Sexual abnormalities, including hypogonadism in males and ovarian tumors.

Oral Manifestations

The odontogenic keratocysts are indistinguishable from those previously described by that term which are not associated with this syndrome (Fig. 4-8). Because they often develop early in life, deformity and displacement of developing teeth may occur. However, they may not develop until middle age even though the basal cell skin tumors have occurred early in life.

Dental Lamina Cyst of Newborn (Gingival cyst of newborn, Epstein’s pearls, Bohn’s nodules)

Clinical Features

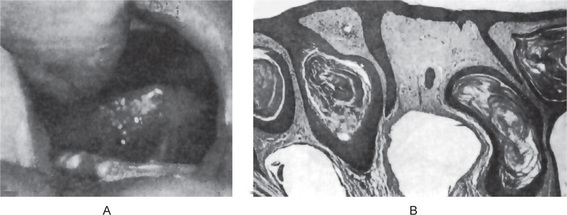

Occasionally these dental lamina cysts in infants become sufficiently large to be clinically obvious as small discrete white swellings of the alveolar ridge, sometimes appearing blanched as though from internal pressure (Fig. 4-9A). These probably correspond to those structures described in the older literature as the ‘predeciduous dentition’. These lesions appear to be asymptomatic and do not seem to produce discomfort in the infants.

Histologic Features

These are true cysts with a thin epithelial lining which lacks rete processes and show a lumen usually filled with desquamated keratin, occasionally containing inflammatory cells (Fig. 4-9B). Interestingly, dystrophic calcification and hyaline bodies of Rushton (q.v.), commonly found in dentigerous cysts, are also sometimes found in this lesion.

Gingival Cyst of Adult

• Heterotopic glandular tissue.

• Degenerative changes in a proliferating epithelial peg.

• Remnants of the dental lamina, enamel organ or epithelial islands of the periodontal membrane.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Inflammatory Cysts

. Inflammatory Cysts . Tumors of Odontogenic Origin

. Tumors of Odontogenic Origin . Odontogenic Epithelium with Odontogenic Ectomesenchyme with or without Hard Tissue Formation

. Odontogenic Epithelium with Odontogenic Ectomesenchyme with or without Hard Tissue Formation . Odontogenic Ectomesenchyme with or without Included Odontogenic Epithelium

. Odontogenic Ectomesenchyme with or without Included Odontogenic Epithelium . Malignant Odontogenic Tumors

. Malignant Odontogenic Tumors . Odontogenic Carcinomas

. Odontogenic Carcinomas