4

Airway devices

Patients undergoing general anaesthesia or sedation are at risk of both airway obstruction (from relaxation of the musculature supporting the upper airway) and apnoea (caused by respiratory depression and/or paralysis). As oxygen storage in the functional residual capacity in the lungs, even after preoxygenation, is very limited (at most 5 minutes in practice, and in many patients much less), restoring airway patency is the most crucial role for any anaesthetist to undertake. Until the airway is patent, attempts to oxygenate the patient are futile and potentially dangerous as the stomach will probably inflate if the lungs do not (see Chapter 17).

There are a number of devices available and they may be classified according to whether the distal end stops above the vocal cords (supraglottic or extraglottic devices) or passes through the vocal cords (infraglottic or subglottic devices). Prior to insertion, remember it may be possible to restore airway patency by simple manoeuvres such as chin lift and jaw thrust. In addition, remember never to insert your fingers into a patient’s mouth and take great care with patients who have loose or crowned teeth.

Supraglottic devices

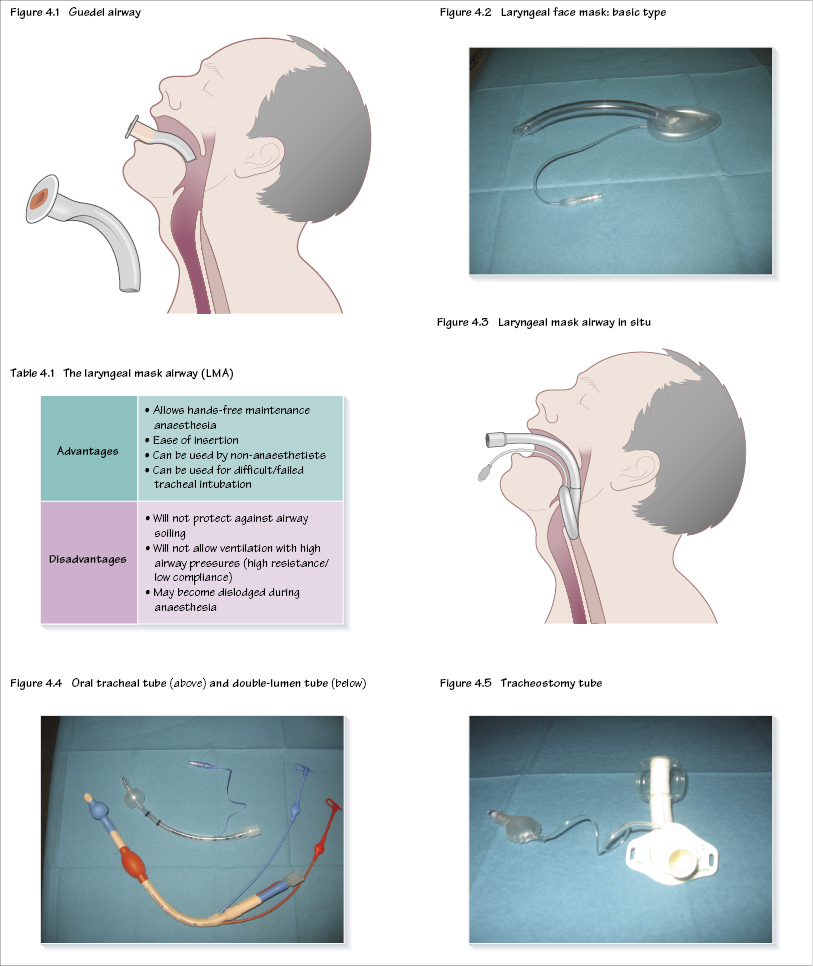

There have been a large number of devices described in recent years. Many of these (e.g. laryngeal mask airway [LMA, see Figure 4.2]) have been developed not only for their ease of insertion and to maintain the airway, but also to free up the hands of the anaesthetist to perform other tasks.

Simple oral (Guedel) airway

This basic airway device is inserted over the tongue to prevent it falling to the back of the mouth (Figure 4.1). It is available in various sizes from neonates to adults. To judge the correct size, use the distance from the chin to the tragus as a guide. A modification is the cuffed oropharyngeal airway (COPA). This has a distal cuff, which pushes the tongue forward and creates an airtight seal, and the proximal end has a standard 15-mm connector, which is suitable for attachment to an anaesthetic circuit.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses