Chapter 4

Acute Oral Medical and Surgical Conditions

Introduction

Oral medicine and oral surgery are specialised branches of dentistry that deal with a wide range of disorders affecting the mouth, face and jaws and which normally require medical or surgical intervention. There is considerable overlap in the range of conditions that present to medical and surgical specialists, but a number of very important clinical conditions can present acutely to dental practitioners.

Whilst the detailed management of these disorders is outside the scope of this book, it is important that the dental emergency clinic practitioner is aware not only of the type and medical significance of such presentations, but also which patients should be referred for specialist assessment and treatment. As most dental emergency clinics function as integral parts of dental hospitals, close working relationships exist with oral and maxillofacial surgery units and oral medicine departments that facilitate such care.

An acute condition may be defined as a suddenly presenting disorder, usually with only a short history of symptoms, but with a degree of severity that causes significant disruption to the patient. They include traumatic injuries (described in Chapter 7), facial pain (which is discussed in detail in Chapter 6), swellings arising both intra-orally and around the face, jaws and neck, blistering and ulcerative disorders of the oral mucosa, disturbed oro-facial sensory or motor function and haemorrhage. This chapter will summarise a wide range of clinical disorders that practitioners should be aware of and which may present as acute conditions in the emergency clinic.

Table 4.1 Signs and symptoms of facial fractures.

| Type of facial fracture | Sign and symptom |

| Unilateral condyle | Fracture side:

|

Opposite side:

|

|

| Bilateral condyle |

|

| Mandible |

|

| Zygomatico-orbital complex |

|

| Middle third fractures |

|

Oro-facial swelling

A swelling is defined as a transient enlargement or protuberance of part of the body and may arise intra-orally or externally around the face, jaws and neck. Acute swellings are usually caused by trauma, or infection and inflammation.

Traumatic swellings include haematoma, facial or dento-alveolar fractures and temporomandibular joint effusions or dislocations. Signs and symptoms that help the clinician to recognise facial fractures are summarised in Table 4.1. Fractures inevitably display localised swelling, bruising and deformity and the patient will experience both pain and some loss of function. The precise history of the preceding injury, examination of the anatomical site involved and standard radiographic assessment will help clarify the diagnosis, and these cases should be referred to specialist oral and maxillofacial surgery opinion.

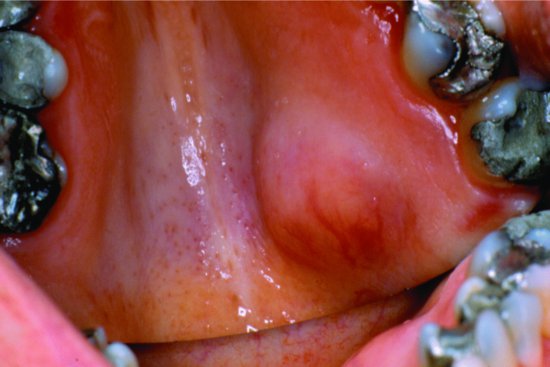

Localised intra-oral swellings are very common, and although sometimes of long standing may present as ‘acute’ problems due to sudden patient awareness. Gingival swellings may represent localised acute periodontal problems or rarer disorders such as giant cell granulomas, whilst palatal swellings can arise from acute dental abscesses or infected odontogenic cysts, particularly involving the lateral incisor or palatal roots of molar teeth, but may be due to other more sinister causes such as minor salivary gland tumours. Tumours arising from minor salivary glands are often malignant and the practitioner should have a high index of suspicion, especially for diffuse, firm palatal swellings in the absence of obvious dental disease. Figure 4.1 illustrates a salivary gland tumour arising in the palate.

Similarly, patients may present with lip swellings that may be diffuse or more localised. Acute, diffuse lip swelling usually represents an allergic response but localised lesions may arise from inflammation or obstruction of minor salivary gland lesions. Whilst mucus extravasation cysts, due to local trauma, account for the majority of lower lip lesions, upper lip swellings are more commonly the result of minor salivary gland tumours.

Acute inflammatory and infective swellings may arise in a number of anatomical sites around the mouth and face, presenting intra-orally as localised dental abscesses or cervico-facial swellings due to spreading tissue space infections. Figure 4.2 shows facial swelling characteristic of a buccal space infection following an intra-oral dental abscess. The various types of clinical presentation, the anatomical sites where infections can localise and their relevant diagnostic features are summarised in Table 4.2.

Figure 4.1 Minor salivary gland tumour arising in palatal tissue.

Figure 4.2 Buccal space infection giving rise to facial swelling.

Table 4.2 Oro-facial tissue space infections.

| Anatomical site | Location | Clinical signs |

| Lower jaw tissue spaces | ||

| Submental | Between mylohyoid above and skin below | Firm swelling beneath chin |

| Submandibular | Between anterior and posterior digastric muscles | Submandibular swelling |

| Sublingual | Lingual mandible between mylohyoid and mucosa | Floor of mouth swelling and raised tongue |

| Buccal | Between buccinator and masseter | Swelling behind angle of mouth to lower mandibular border |

| Submasseteric | Between masseter and lateral ramus | Trismus, swelling confined to masseter |

| Pterygomandibular | Between medial pterygoid and medial ramus | Severe trismus, dysphagia, limited buccal and submandibular swelling |

| Lateral pharyngeal | Skull base to hyoid, medially pharyngeal muscle, laterally fascia | Pyrexia, malaise, dysphagia, trismus, swollen fauces |

| Peritonsillar | Between pharyngeal muscle and tonsil | Dysphagia, ‘hot potato’ speech, swollen fauces and soft palate |

| Upper jaw tissue spaces | ||

| Lip | Between orbicularis oris and mucosa | Diffuse labial swelling |

| Canine fossa | Between levator muscles and facial skin | Diffuse swelling lip, cheek and lower eyelid |

| Palatal | Subperiosteal space | Circumscribed fluctuant palatal swelling |

| Infratemporal fossa | Below greater wing of sphenoid, ramus lateral and pterygoid plate medial | Trismus, pyrexia |

| Subtemporalis | Between temporal bone and temporalis muscle | Temporal swelling, trismus |

The rapid spread of infection through connective tissue spaces, often referred to as cellulitis, can give rise to airway obstruction and life-threatening conditions, such as Ludwig’s angina, which is a large infective swelling involving bilateral submandibular, sublingual and submental spaces. Swelling may extend down the anterior neck, with massive distension of the floor of the mouth and elevation and protrusion of the tongue. Such presentations are acute surgical emergencies and require immediate referral.

The cardinal signs of acute inflammation comprise swelling (often with resultant suppuration and abscess formation), pain, redness, heat and loss of function. Sometimes, patients may present with cutaneous swellings or sinuses as a result of discharge of infected material from dental abscesses. There may also be systemic signs such as pyrexia, malaise, sweating, dehydration and rapid pulse.

Clearly, clinical management is dependent upon the precise cause of infection and the general state of the patient. Localised dento-alveolar abscesses may be appropriately treated by intra-oral drainage via tooth extraction, opening of root canals and/or intra-oral incision and drainage. Wherever there are signs of spreading cervico-facial infection or significant systemic disturbance, however, patients should be referred urgently to the maxillofacial unit for admission and further management.

One of the commonest acute oral surgery conditions to present to the emergency clinic is pericoronitis, inflammation around the crown of a partly erupted or impacted tooth usually the mandibular third molar. In acute cases, the patient experiences pain and swelling around the tooth, together with a foul taste and often halitosis. There may also be trismus, dysphagia, facial swelling and pyrexia. Diagnosis follows radiographic examination and confirmation that the infection has not arisen from infected adjacent teeth. Extraction of traumatic upper third molars, localised antibacterial treatment and antibiotic prescription may be required to ease the acute condition before referral for specialist advice on surgical removal. As in all infective conditions, rapidly spreading facial or neck swelling requires urgent referral and hospital admission.

A number of acute oral mucosal infections, such as pseudomembranous candidiasis or herpetic gingivostomatitis may give rise not only to classical intra-oral discomfort or ulceration but also to labial and facial swelling and cervical lymphadenopathy.

Acute swelling of the major salivary glands may also present to the dental emergency clinic. Whilst an acute bacterial parotitis, usually a consequence of dehydration or obstructed salivary flow, is rarely seen these days, viral parotitis due to mumps infection is becoming more common. In the UK, in particular, this may be related to a lack of uptake of the MMR vaccine due to adverse publicity in the late 1990s. Whilst the classic description of mumps emphasises bilateral parotid swelling with everted earlobes and accompanying submandibular swelling, patients often present initially with an acute unilateral parotid swelling that may pose a diagnostic dilemma.

Isolated acute submandibular salivary gland swellings are less common, more usually presenting as intermittent obstructive swellings due to calculus formation in the ductal system. The history and clinical examination is usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis. Salivary gland disorders are best referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery specialists for further investigation and management.

Swellings may also present as more discrete neck lumps. Whilst there is a wide range of causes for a lump in the neck, summarised in Table 4.3, many of these may be long-standing, chr/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses