39 Endodontic Retreatment Procedures

Good to very good long-term prognosis for initial endodontic treatment has been demonstrated in controlled clinical studies. Retrospective as well as randomized clinical studies have demonstrated healthy periapical conditions after an observation time of 4 or more years in more than 90% of all cases of teeth treated endodontically (Strindberg 1956; Molven et al., 2002; Farzaneh et al., 2003). Periapical periodontitis is a significant factor that influences prognosis. In teeth with periapical disease at the start of retreatment procedures, the Toronto study demonstrated that after 4–6 years, almost 80% of the retreated teeth exhibited a healthy periapical condition (Farzaneh et al., 2004).

On the other hand, epidemiologic studies have shown that the aforementioned good treatment results are only seldom achieved in general dental practice. Overall, 25%–35% of teeth treated endodontically in a general dental practice will have persisting apical periodontitis. The quality of the root canal filling was determined to be a criterion that significantly influenced the overall clinical result (De Moor et al., 2000; Kirkevang and HorstedBindslev, 2002).

If it is not possible to reduce the level of microbial infection of the complex root canal system to at least below a clinically relevant level, the periradicular lesion will not heal or will only heal incompletely. Common causes of failure of the root canal treatment are: inadequate asepsis, inadequate access cavity preparation, undetec ted (missed) and therefore unfilled root canals, insufficient instrumentation and root canal filling technique, as well as coronal leakage.

Nonsurgical retreatment remains the treatment of choice in cases of persisting periapical periodontitis. In contrast to a surgical procedure, it offers a minimally invasive approach to the cause of the problem without the danger of damage to adjacent anatomic structures; it is also associated with significantly lower postoperative discomfort for the patient (Friedman, 2002). But even carefully carried out endodontic treatment can end in failure when the extremely complex root canal system can be only partially cleansed and filled three-dimensionally using the treatment techniques currently available.

Additional causes of the persistence of periapical radiolucencies include the so-called extraradicular infections, e.g., Actinomyces, foreign-body reactions (e.g., filling materials, presence of cotton fibers, food particles, etc.), infected cysts, or the scarred healing of the periapical tissues (Nair, 2006). In such cases, a microsurgical approach is recommended. On the basis of a meta-analysis, Friedman (1998) demonstrated that surgical root canal therapy in combination with orthograde retreatment led to significantly better results.

If endodontic retreatment is deemed necessary, several—some very complex—factors must be considered during treatment planning. The clinician must have a clear understanding of the etiology and pathology of the periapical lesion, the microbiology, as well as the technical possibilities and limitations of the retreatment procedure. It is important to note that the success of the endodontic retreatment procedure is highly dependent on the degree of training/education of the clinician. As this may be out of the scope of experience and expertise of the general dentist, referral of such cases to a specialist with appropriate experience and knowledge may be appropriate.

No less important is the participation of the patient in the discussion of retreatment possibilities, with all due consideration of the costs and risks.

Decision Criteria

When Should Retreatment be Considered?

If endodontically treated teeth exhibit persisting or acute clinical symptoms, lesions of endodontic origin (Kvist, 2001), or periodontal disease as a result of endodontic problems, retreatment should be considered.

Also restorative problems, such as reinfection of the root canal system because of coronal leakage or the necessity for additional restorative treatment in the face of inadequate root canal therapy, represent indications for endodontic retreatment. On the other hand, orthograde retreatment may be contraindicated if no pathology is present or if the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of retreatment or the higher costs that are often associated with necessary prosthetic retreatment.

Alternative treatment strategies including consultations with other specialists (prosthodontist, periodontist, implantologist, orthodontist) should be a part of the treatment planning, and should be openly discussed with the patient.

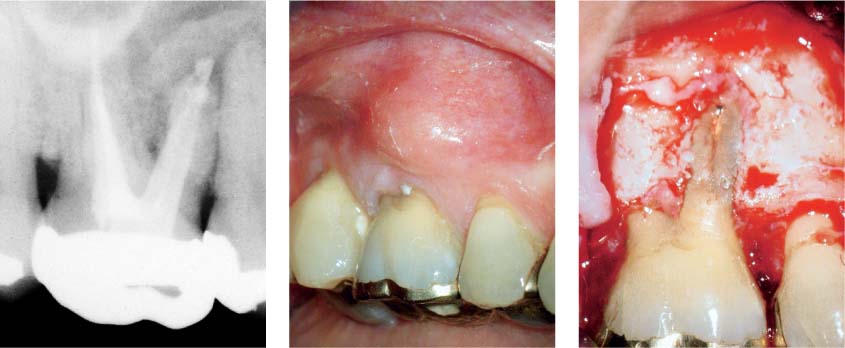

39.1 Clinical symptoms

Left: Acute periradicular abscess extending from the endodontically treated tooth 16.

Middle: Intraorally, there is a buccal swelling.

Right: Combined perioendo lesion with total destruction of the vestibular bone over the mesiobuccal root.

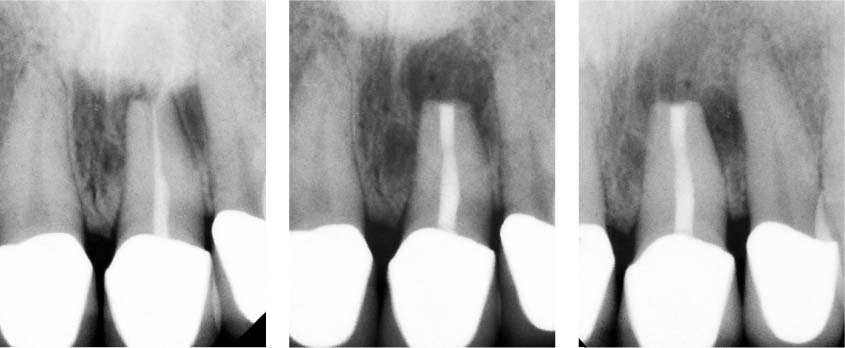

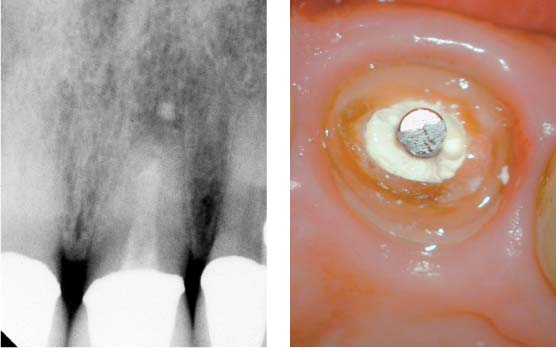

39.2 Lesion of endodontic origin

Left: Extensive lesion of endodontic origin resulting from underfilling of the root canal system and an extruded gutta-percha point.

Middle: Situation following ortho-grade retreatment with maintenance of the restoration (apical root canal filling with mineral trioxide aggregate [MTA], adhesive build-up with a glass-fiber post and composite, as well as cystectomy).

Right: Six-month follow-up radiograph of the functional and symptom-free tooth, demonstrating apical regeneration.

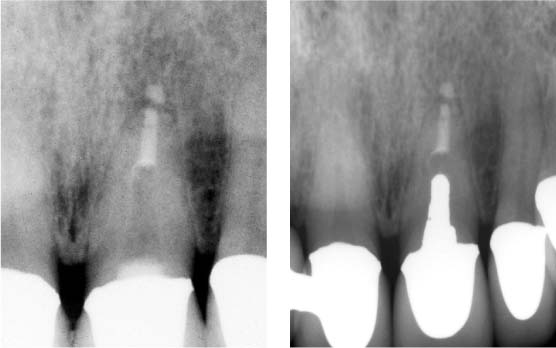

39.3 Coronal leakage

Left: Because of its open margin, the crown on tooth 36 must be replaced. Owing to coronal leakage, the inadequate root-canal filling, and the chronic apical periodontitis, the root canal must be retreated.

Middle: Radiographic view following retreatment, root canal obturation, and adhesive build-up.

Right: Follow-up radiograph taken 6 months later with the new definitive restoration; note the increasing resolution of the periapical radiolucency.

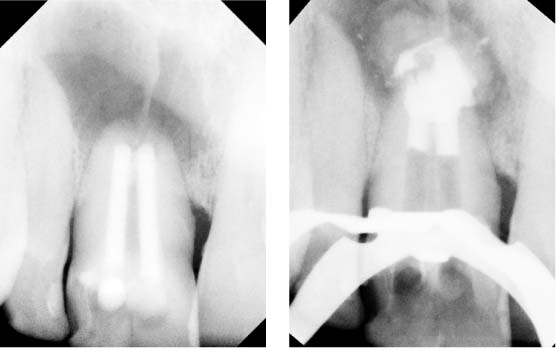

39.4 Deficient restoration as a cause of a lesion of endodontic origin

Left and middle: Endodontic therapy on tooth 26 was carried out 15 years earlier. The patient is free of symptoms but the tooth requires full crown coverage because of the defective amalgam restoration. The obvious apical radiolucency on the radiograph and coronal leakage mean that endodontic retreatment is the indicated procedure.

Right: Clinical view following removal of the majority of the amalgam restoration.

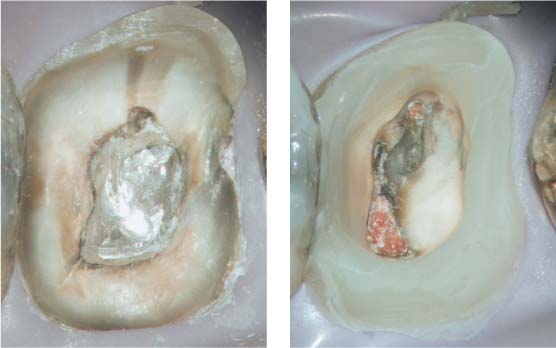

39.5 Preliminary treatment

Left: Complete removal of all secondary caries.

Right: Adhesive composite build-up to prevent bacterial contamination during the stage of dressing the root canal with calcium hydroxide.

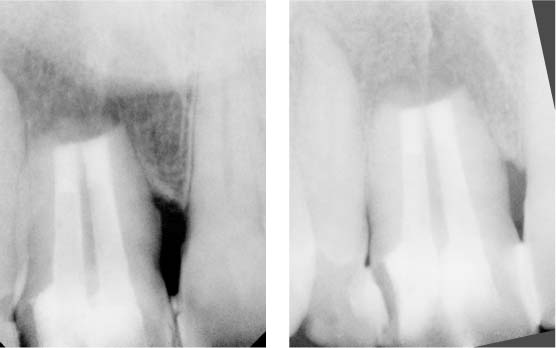

39.6 Results

Left: Radiograph immediately following endodontic retreatment and filling.

Right: Six-month recall radiograph reveals complete healing of the apical lesion.

39.7 No retreatment indicated

Underfilled canal system. Teeth 37 and 36 had received partial gold crowns 15 years previously, and showed perfect margins and functional occlusal morphology. The patient was free of clinical symptoms despite a slight widening of the periodontal ligament space on the radiograph.

Left: Underfilled root canals with apical ledge formation. The tooth has served as a bridge abutment for 12 years and the restoration is fully functional. The periodontal ligament space is not widened and the lamina dura is intact.

Timing of Root Canal Therapy

The prevention or the healing of apical periodontitis (AP) as well as the long-term retention of the tooth in a functional and symptom-free condition is the goal of any endodontic treatment. On this basis, endodontic therapy can be termed “successful” when the tooth remains healthy without any radiographic evidence of periapical inflammation or destruction and when there are no clinical symptoms or other signs of inflammation.

On the other hand, a clinical “failure” is characterized by the persisting presence of periradicular inflammation and/or the occurrence of clinical symptoms and signs of inflammation. In this regard, one must differentiate between such cases and those that exhibit typical signs of periapical inflammation but are nevertheless in the healing phase.

Apical periodontitis can take up to 4 years or more to completely heal, but in 89% of cases radiographic signs of healing can be observed after only 1 year (Orstavik, 1996).

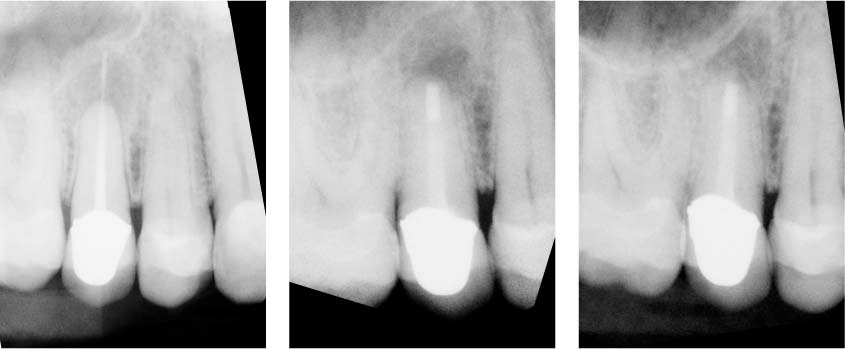

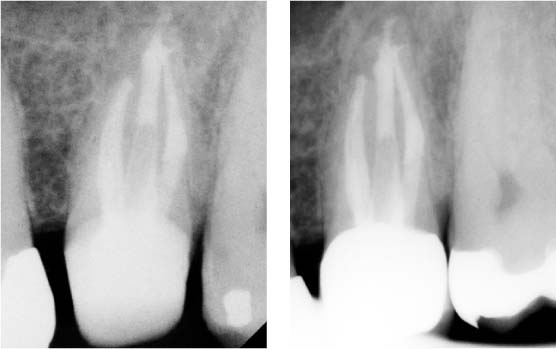

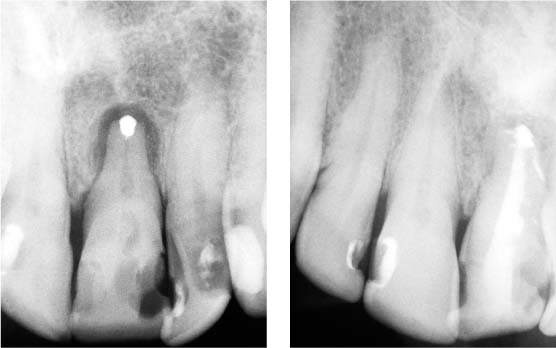

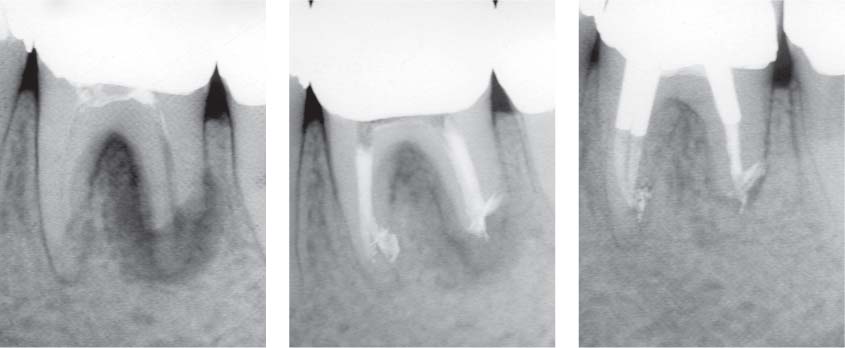

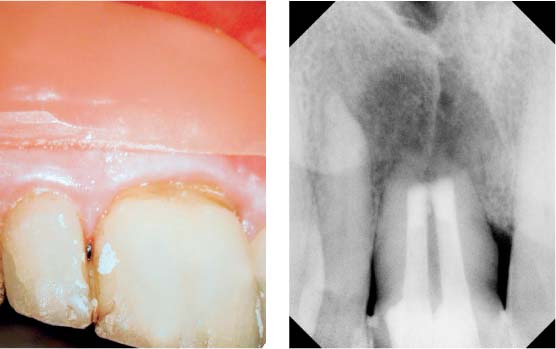

39.8 Healed apical periodontitis

Left: Initial radiograph of teeth 11 and 21, both with incomplete root canal fillings as well as radiographic signs of chronic apical periodontitis (CAP).

Middle: Six months later the lateral lesion on tooth 21 shows signs of healing.

Right: Radiographically intact periapical appearance and freedom from clinical symptoms 3 years later.

39.9 Healing of apical periodontitis

Left: Lateral and apical lesions of endodontic origin associated with tooth 44.

Middle: Appearance following 4 weeks of a calcium-hydroxide dressing and root-canal filling.

Right: In comparison with the initial situation, 3 months later there is clear evidence of healing, although this is not yet complete.

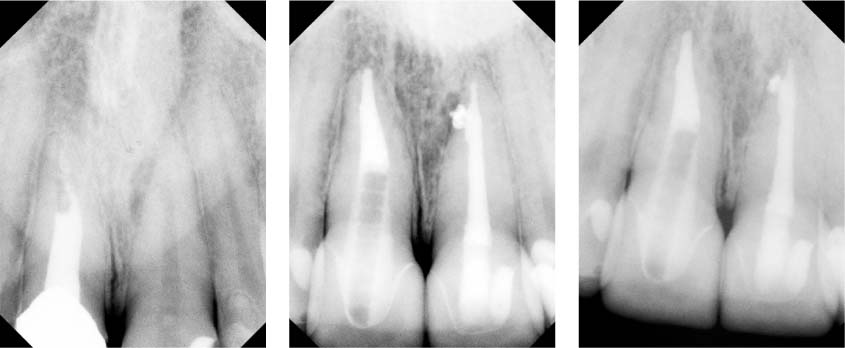

39.10 Persisting apical periodontitis

Left: Tooth 21 exhibits an incompletely filled root canal system and an extensive periapical radiolucency.

Middle: Radiograph following orthograde retreatment, cystectomy and retrograde filling with MTA.

Right: Three years later, the tooth is functional and symptom-free.

Can the Tooth be Saved?

Teeth being considered for endodontic retreatment must be carefully examined with regard to their periodontal integrity. Deep probing depths, mobility, furcation involvement, unfavorable crown–root ratio, bone loss, and mucogingival problems can negatively influence the long-term prognosis of the tooth (Kois, 1996). Teeth requiring endodontic retreatment often exhibit pronounced loss of tooth structure, subgingival caries, or perforations at the level of the alveolar crest.

For a good, long-term prognosis of the subsequent prosthetic treatment, sufficient dentin for the “ferrule effect” (Sorensen, 1980) and an intact biologic width must exist (Ross and Garguilo, 1982). In addition, purely endodontic problems such as external root resorption can negatively influence the longevity of any tooth (Heithersay, 2004).

39.11 Combined perio-endo lesion

Left: Initial radiograph of tooth 21 reveals a periapical radiolucency, a partially obliterated root canal system, and a retrograde filling. Probing depths were up to 4 mm.

Right: Radiographic view following orthograde root canal treatment. There is evidence of leakage around the apical amalgam restoration because of penetration of the sealer into the periapical region.

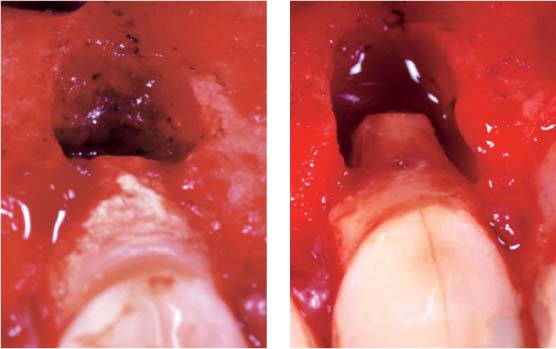

39.12 Periapical lesion of primary endodontic origin and secondary periodontal origin: clinical view of the defect 4 weeks after orthographic retreatment

Left: Surgical view following reflection of a mucoperiosteal flap. The extensive calculus deposits and the periodontal defect are now clearly visible. The diagnosis was a combined perio-endo lesion.

Right: Surgical view following periapical curettage, retrograde root-canal filling with SuperEBA, and cleansing and conditioning of the root surface with citric acid.

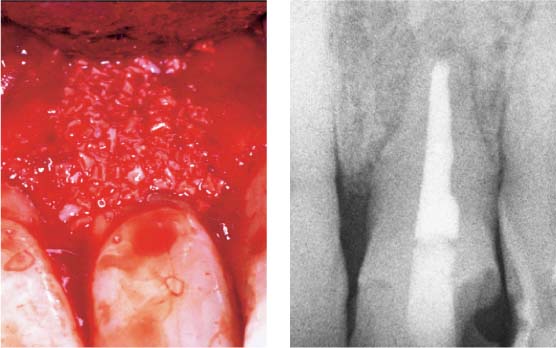

39.13 Treatment of periodontal destruction

Left: Guided bone regeneration with Bio-Oss and a membrane (ATRISORB). (Courtesy of Dr. E. Hernichel-Gorbach, MSD.)

Right: Radiographic view following completion of the retreatment; the prognosis remains uncertain.

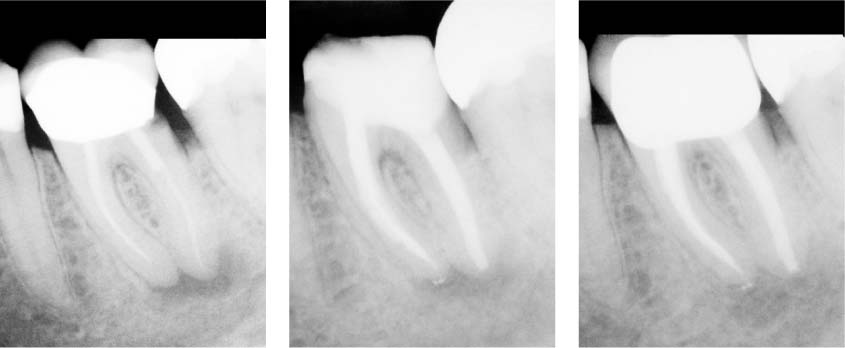

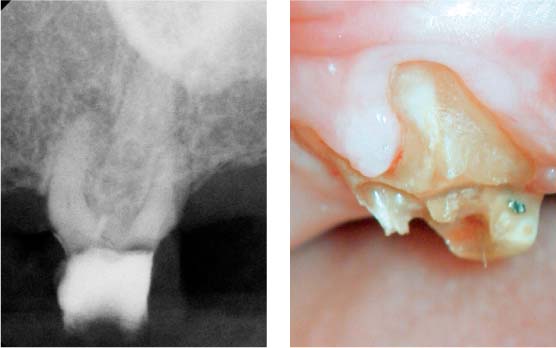

39.14 Lesion of primary endodontic and secondary periodontal origin

Left: Initial situation of tooth 47 with pulpal necrosis and chronic apical periodontitis.

Middle: Isolated periodontal defect on the lingual aspect, probing depth 9 mm, and grade 2 furcation involvement. Preliminary diagnosis was a primary endodontic and a secondary periodontal problem.

Right: Dentin fracture extending mesiodistal beneath an old restoration (arrow).

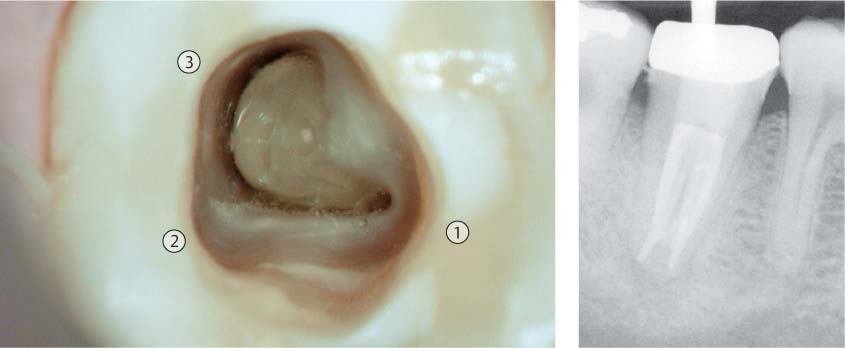

39.15 Primary endodontic, secondary periodontal lesion

Situation following adhesive build-up restoration and preparation of the access cavity. The so-called C-shaped canal configuration is obvious, with confluence of the mesiobuccal with the distal canal systems (1: mesiolingual; 2: mesiobuccal; 3: distal).

Right: Following completion of treatment. The periodontal situation should be re-evaluated in 2–3 months. The prognosis is guarded because of dentin fracture. Treatment involved a temporary crown.

39.16 Periodontal problem: true combined perio-endo lesion

Because of the extent of the periodontal defects on the two anterior teeth (left) and the canine (right), endodontic retreatment in combination with periodontal therapy is not the indicated treatment here; extraction is recommended.

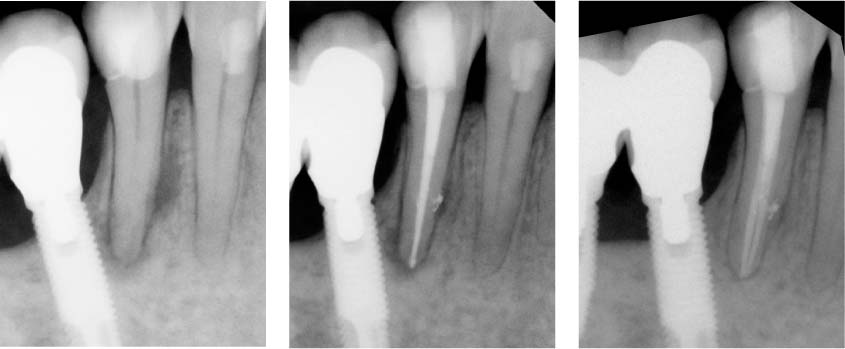

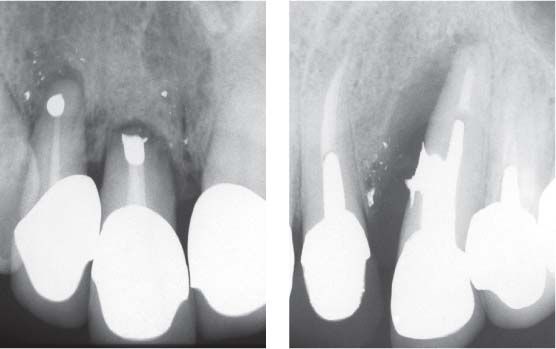

39.17 Periodontal problem: primary endodontic lesion with grade 2 furcation involvement

Left: Initial situation following previous endodontic therapy. Progression of the lesion of endodontic origin into the furcation area and extensive apical root resorption.

Middle: Radiograph following retreatment of the root canals.

Right: Follow-up radiograph 6 months later. It was not possible to explore the furcation defect with a probe, but there are radiographic signs of osseous regeneration.

Left: The preoperative radiograph of the maxillary molar reveals a severely obliterated root canal and almost complete destruction of the tooth crown itself. Note also the horizontal bone loss.

Right: Because of the extensive damage to the hard tissues, this tooth will continue to be at an increased risk of fracture.

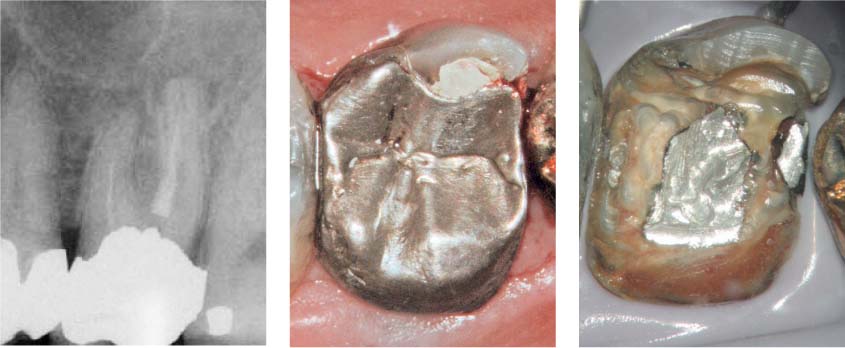

39.19 Restorative problems I

Left: The tooth was endodontically retreated despite the patient’s advanced age of 87 years and the general medical risks of brittle type 2 diabetes.

Right: One-year follow-up radiograph reveals healing of the AP; the patient was clinically symptom-free. This tooth served as an abutment for a telescopic removable partial denture.

39.20 Restorative problems II

Left: Acute periradicular abscess in relation to tooth 21. Ten years previously the tooth had been endodontically treated. Three years previously it had undergone root resection, and the entire anterior segment had been recently restored. The tooth exhibits an unfavorable crown–root ratio.

Right: Clinical view after removal of the temporarily cemented crown.

39.21 Restorative problems II

Left: Radiographic view immediately following retreatment of the root canal. Because of the large size of the foramen, an apical root filling with MTA was placed and the canal was prepared to receive a post-and-core restoration.

Right: One-year radiographic follow-up. The post does not fill the root canal completely. This tooth is highly susceptible to fracture because of the unfavorable leverage provided by the post as well as the extensive loss of hard tissue.

Left: Tooth 11 fused with a supernumerary tooth exhibiting massive periapical radiolucency. The tooth was treated endodontically 22 years previously, and underwent root re-section 3 years previously. Now it was associated with an acute abscess.

Right: Radiographic view following numerous calcium-hydroxide dressings and the apical closure MTA. An attempt to create a periapical barrier using calcium sulfate was only partially successful.

39.23 Endodontic problems

Left: Radiographic follow-up after periapical curettage, correction of the bevel of the resected root surface, and partial removal of the cystic lesion. Histologic examination revealed a radicular cyst. The tooth was subsequently built up using glass-fiber posts and composite resin.

Right: Clinical view following the surgical procedure. An opening was created to allow the cyst to heal.

39.24 Endodontic problems

Left: Seating of the obturator.

Right: The 3-month postoperative radiograph demonstrating progression of osseous regeneration.

39.25 Endodontic problems

Left: Radiographic check-up 9 months later exhibits further resolution of the osseous defect.

Right: The follow-up examination 2 years later reveals />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses