Prevention of Dental Disease

The period encompasses the completion of physical growth and development in both girls and boys. All permanent teeth have erupted except for the congenitally missing or impacted third permanent molars. The occlusion has stabilized either on its own or with orthodontic intervention. Most studies show a gradual but general increase in the incidence of dental caries during this period.1 Periodontal disease may become clinically evident because there are fewer routine and supervised home care sessions as well as less frequent professional interventions. In addition, the increase in sex hormones in this age group is suspected to alter the subgingival microflora, resulting in an increased incidence of periodontal disease.2

Risk Assessment

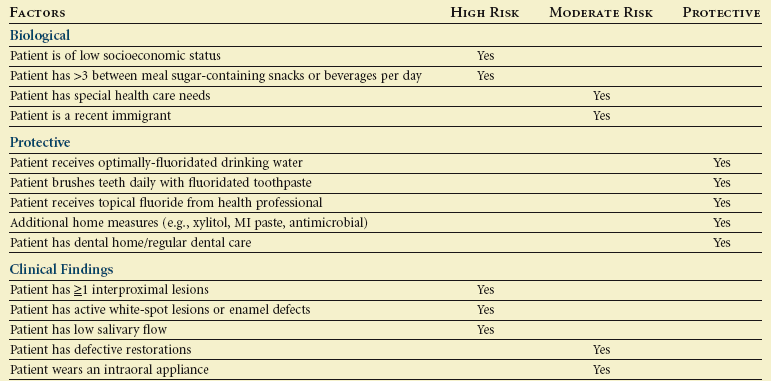

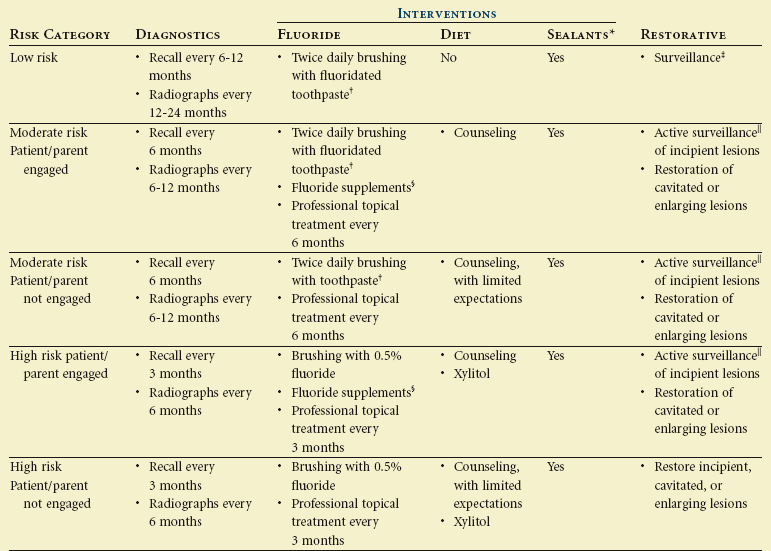

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) has developed a set of guidelines used to assess the caries risk of patients in the mixed or permanent dentition (Table 38-1). In addition, the AAPD has developed caries management protocols based on these risk assessments (Table 38-2). Although these protocols are useful in determining the direction of patient care, they should be considered as guidelines only, and each adolescent should have an individualized treatment plan that addresses their unique preventive, restorative, and counseling needs.

TABLE 38-1

TABLE 38-1

Caries-Risk Assessment Form for Patients Older than 6 Years (For Dental Providers)

Overall assessment of the dental caries risk: Low  Moderate

Moderate  High

High

From American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents, Pediatr Dent 33:110–117, 2011.

TABLE 38-2

TABLE 38-2

Example of a Caries Management Protocol for Patients Older than 6 Years

*Indicated for teeth with deep fissure anatomy or developmental defects.

†Less concern about the quantity of toothpaste.

‡Periodic monitoring for signs of caries progression.

§Need to consider fluoride levels in drinking water.

Careful monitoring of caries progression and prevention program.

Careful monitoring of caries progression and prevention program.

From American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents, Pediatr Dent 33:110–117, 2011.

Dietary Management

The sense of independence among adolescents often leads to snacking at will. Such poor eating habits are a major factor in the increasing rates of childhood obesity.3 Often these poor eating patterns carry over into adulthood. The National Health and Nutrition Examination, 2005-2006 (NHANES) investigated the change in snacking habits of adolescents since the late 1970s. Several troubling issues were identified:

• The number of adolescents who snack on a given day increased from 61% in 1977-1978 to 83% in 2005-2006.

• Snacking, which accounted for 300 calories a day in 1977-1978, accounted for 526 calories a day in 2005-2006.

• Those adolescents who snacked frequently were more likely to have a higher total daily calorie intake.4

The busy lifestyles of adolescents today make the sit-down family meal a rarity. This has a deleterious effect on the dietary patterns of adolescents. Research has shown that parental presence at family evening meals exerts substantial influences in terms of the adolescents’ consumption of fruits, vegetables, and dairy products.5

A growing trend among adolescents is the consumption of sports drinks and energy drinks (Figure 38-1). Adolescents, as well as their parents, often fail to recognize the difference between these two.6 Sports drinks are promoted by the beverage industry as products that optimize athletic performance by replacing fluid and electrolytes lost in vigorous exercise. In contrast, energy drinks purport everything from an increase in energy and a decrease in fatigue to enhanced mental alertness and focus. These energy drinks typically contain a blend of stimulants that include caffeine, taurine, ginseng, guarana, l-carnitine, and creatine. Some of these energy drinks exceed 500 mg of caffeine in a single serving, which is equivalent to the amount of caffeine found in 14 cans of the typical caffeinated soft drink.7 Caffeine adversely affects the physiologic as well as the mental function of an individual. It tends to increase blood pressure, heart rate, gastric secretions, body temperature, cardiac arrhythmias, and diuresis.8 For those individuals with increased anxiety, it makes them more prone to anxiety disorders.9

FIGURE 38-1 Sport drinks (A) versus energy drinks (B).

FIGURE 38-1 Sport drinks (A) versus energy drinks (B).

Both parents and school systems are recognizing the harmful dental effects of carbonated sodas and similar beverages and limiting the exposure of adolescents to them. Unfortunately, these carbonated beverages are frequently being replaced with sports drinks. The pH of most sports drinks are in the acidic range (pH 3 to 4), which is well within the range to cause enamel demineralization.10 It is unfortunate that parents and school administrators are failing to recognize the deleterious effects of sports drinks on the dentition.

• Improve the education to both parents and children on the differences as well as the potential health risks of sports drinks and energy drinks

• Understand the potential health risks that energy drinks pose as a result of their stimulant content

• Counsel at-risk individuals as to the relationship between both obesity and dental erosion to excessive sports drink consumption

• Educate patients and parents on effective hydration management, stressing that water should be the initial beverage of choice for hydration purposes

According to the commission’s report, energy drinks have no place in the diet of adolescents.11

Although sports drinks and energy drinks are a somewhat new trend among adolescents, the problem associated with the consumption of high-sugar beverages of any type is long-standing in this age group. Sugar-sweetened beverages have become the largest source of added sugars in the diet of adolescents in the United States.12 These beverages include nondiet sodas, sweetened fruit juices, sweetened coffee and tea drinks, and the sport and energy drinks. Some studies are attributing the increased caloric intake associated with the consumption of these beverages as a factor that is contributing to the increasing obesity rates among adolescents.13 In addition, the high sugar content of sugar-sweetened beverages has been shown to increase the risk of type 2 diabetes by increasing the dietary glycemic load, leading to insulin resistance and β cell dysfunction.14 Data from the 2010 National Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Study (NYPANS) revealed that 62.8% of high school students drank at least one sugar-sweetened beverages daily, and 32.9% drank two or more daily.15 The elevated consumption of these beverages not only affects the overall general health of adolescents in the form of increasing rates of obesity and diabetes but also has deleterious effects on the caries rates of adolescents.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline