Chapter 35 Oral mucosal and salivary gland infections

Oral mucosal infections

Oral candidiasis (synonym: oral candidosis)

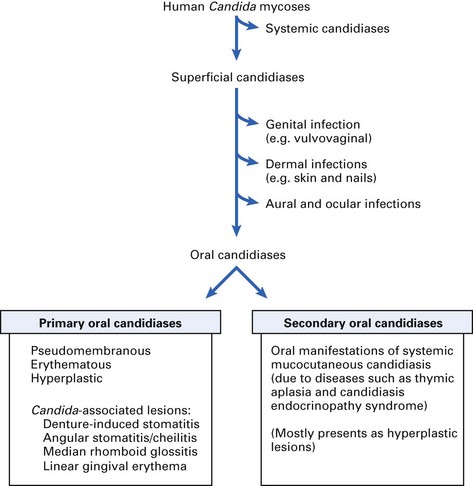

Classification

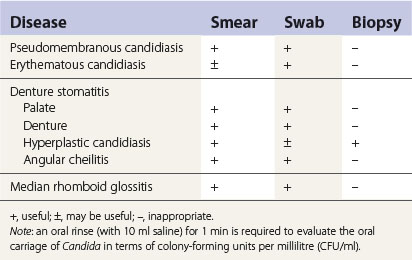

Oral candidiases can be classified as follows (Fig. 35.1):

The classic triad of (either primary or secondary) oral candidiases are:

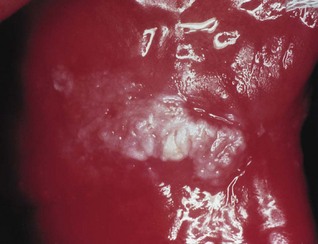

Pseudomembranous candidiasis

Pseudomembranous candidiasis, classically termed ‘thrush’ (Fig. 35.2), is an acute infection but may persist intermittently for many months or even years in patients using corticosteroids topically or by aerosol, in HIV-infected individuals, and in other immunocompromised patients. It may also be seen in neonates and in the terminally ill, particularly in association with serious underlying conditions such as leukaemia.

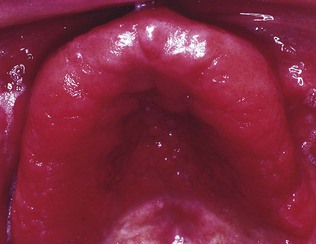

Erythematous (atrophic) candidiasis

Clinical features

The clinical presentation is of one or more asymptomatic erythematous areas, generally on the dorsum of the tongue, palate or buccal mucosa (Fig. 35.3). Lesions on the dorsum of the tongue present as depapillated areas; red areas are often seen on the palate in HIV disease.

Fig. 35.3 Erythematous candidiasis of the palate in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individual.

There can be associated angular stomatitis, especially in Candida-associated denture stomatitis.

Hyperplastic candidiasis (Candida leukoplakia)

The lesions in hyperplastic candidiasis present as chronic, discrete raised areas that vary from small, palpable, translucent, whitish areas to large, dense, opaque plaques (Fig. 35.4), hard and rough to the touch (plaque-like lesions). Homogeneous areas or speckled areas that do not rub off (nodular lesions) can also be seen. The lesions are often asymptomatic and usually occur on the inside surface of one or both cheeks (retrocommissural area). Oral cancer supervenes in 9–40% of cases of hyperplastic candidiasis, as compared with the 2–6% risk of malignant transformation cited for oral white patches in general. Therefore, patients with recalcitrant hyperplastic candidal lesions resistant to therapy should be kept under regular surveillance.

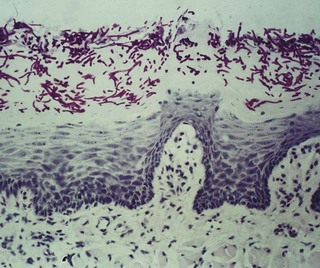

Microbiology and histopathology

Parakeratosis and epithelial hyperplasia occur, with candidal invasion restricted to the upper layers of the epithelium (Fig. 35.5). The condition has been associated in a minority with iron and folate deficiencies and with defective cell-mediated immunity. Biopsy is important as the condition is premalignant and shows varying degrees of dysplasia.

Candida-associated lesions

Candida-associated denture stomatitis

Aetiology

Treatment

Angular stomatitis (perleche, angular cheilitis)

The lesions of angular stomatitis are seen in one or both angles of the mouth (Fig. 35.8), especially as a complication of Candida-associated denture stomatitis.

Fig. 35.8 Angular cheilitis in a denture-wearer. Note the yellow crusting due to staphylococcal infection.

Clinical features

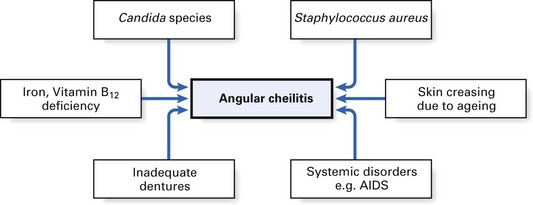

Characterized by soreness, erythema and fissuring, this condition is commonly associated with denture-induced stomatitis. Both yeasts and bacteria (especially Staphylococcus aureus) are involved as interacting predisposing factors. However, angular stomatitis is very occasionally an isolated initial sign of anaemia or vitamin deficiency, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, and resolves when the underlying disease has been treated. The condition is also seen in HIV-associated disease (Fig. 35.9).

Treatment

Median rhomboid glossitis

Midline glossitis, or glossal central papillary atrophy, is characterized by an area of papillary atrophy that is elliptical or rhomboid in shape and symmetrically placed centrally at the midline of the tongue, anterior to the circumvallate papillae (Fig. 35.10). Occasionally, median rhomboid glossitis presents with a hyperplastic exophytic or even lobulated appearance. In addition to fungal infection, a number of predisposing cofactors, including smoking, steroid inhalation and remnants of the tuberculum impar, have been proposed.

Candidiasis and immunocompromised hosts

A few patients have chronic candidiasis from an early age, sometimes with a definable immune defect, e.g. chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (Figs 35.11 and 35.12). Candidal infections in these patients are seen in the oral mucosa, skin and other body parts. These secondary oral candidal infections have increased recently because of the high prevalence of attenuated immune response, consequent to diseases such as HIV infection, haematological malignancy and treatment protocols, including aggressive cytotoxic therapy.

Fig. 35.12 Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis: hyperplastic lesions of the tongue in the same patient shown in Figure 35.11.

Oral candidiasis in HIV disease

Candidal infections, with oral thrush and oesophagitis as frequent clinical manifestations, are the most common opportunistic infections encountered in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). It has also been shown that the occurrence of an otherwise unexpected mycosis (typically oral candidiasis) in an HIV-infected individual is a poor prognostic indicator of the subsequent development of full-blown AIDS (see also Chapter 30). However, in HIV-infected populations on antiretroviral therapy, the incidence of oral candidiasis has significantly declined.

Oral manifestations of systemic mycoses

Treatment

Almost all dimorphic fungi are sensitive to amphotericin; fluconazole may be an alternative.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses