Chapter 30 Human immunodeficiency virus infection, AIDS and infections in compromised patients

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome

Definitions

Retroviridae

Human immunodeficiency virus

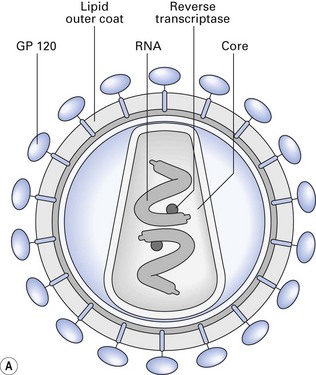

The structure of HIV is shown in Figure 30.1. It consists of:

Stability of HIV

The survival of HIV under varying conditions has been investigated.

Transmission of HIV

Saliva and HIV transmission

Epidemiology

The main groups of individuals affected are:

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

Natural history of the disease

AIDS is an insidious disease, characterized by opportunistic infections (fungal, viral and mycobacterial), malignancies (especially Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphomas that may be virally induced) and autoimmune disorders (Fig. 30.2).

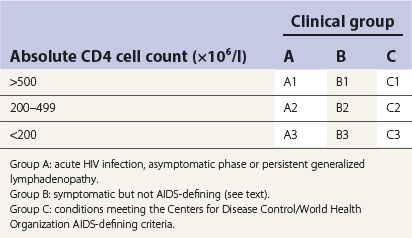

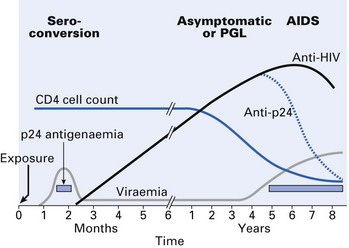

Mean time for seroconversion after exposure to HIV is 3–4 weeks, with the onset of an acute seroconversion illness similar to glandular fever. Most will have antibodies within 6–12 weeks after infection and virtually all will be positive within 6 months. Symptoms of such seroconversion include fever, malaise, rash, oral ulceration and, occasionally, encephalitis and meningitis. In some, the disease may then become quiescent and asymptomatic for several years (range 1–15 years or more) for reasons yet unknown. Some of them may have persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (PGL), where the enlarged lymph nodes are painless and asymmetrical in distribution and involve submandibular and neck nodes. In the HIV disease classification, patients with these symptoms are categorized as group A (Table 30.1).

Finally, a percentage of HIV-infected individuals develop full-blown AIDS (50–70% depending on drug therapy and other associated cofactors; median life expectancy is 18 months). These individuals are in group C. The AIDS-defining conditions are subdivided into opportunistic infections and secondary neoplasms, and include Kaposi’s sarcoma, PCP and many other exotic infections (Table 30.2).

Table 30.2 Opportunistic infections, neoplasms and miscellaneous complications of HIV disease

| Opportunistic infections | |

| Mucocutaneous | Human herpesviruses |

| 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 | |

| Human papillomaviruses | |

| Molluscum contagiosum | |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria | |

| Candida albicans | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Histoplasmosis | |

| Gastrointestinal | Cryptosporidiosis |

| Microsporidiosis | |

| Isosporiasis | |

| Giardiasis | |

| Respiratory | Pneumocystis carinii |

| Aspergillosis | |

| Candidosis | |

| Cryptococcosis | |

| Histoplasmosis | |

| Zygomycosis (mucormycosis) | |

| Strongyloidosis | |

| Mycobacteria, including tuberculosis | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | |

| Toxoplasmosis | |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | |

| Meningitis | Creutzfeldt–Jakob agent |

| Encephalitis | Papovaviruses |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | |

| Toxoplasma gondii | |

| Neoplasms | |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| Lymphoma | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Leukaemia | |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Encephalopathy | |

| Thrombocytopenic purpura | |

| Lupus erythematosus | |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis |

The Centers for Disease Control disease classification also incorporates blood CD4 lymphocyte count, as a decrease in the latter is associated with adverse prognosis (Table 30.1).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses