Chapter 3

Quality Concepts

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to review some of the common quality concepts and frameworks and how they can be used to help develop quality initiatives in everyday practice.

Outcome

The reader should be familiar with some key quality concepts that can have an impact on the implementation of a quality programme in general dental practice.

Introduction

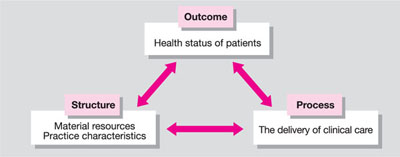

Of the many quality assessment frameworks that exist, Donabedian’s (1966) concept is perhaps the most applicable to all aspects of general dental practice. In his classic text on healthcare quality, Avedis Donabedian presents a fundamental concept regarding the nature of any activity designed to produce a consistent result. The concept (Fig 3-1) has three attributes:

-

Structure

-

Process

-

Outcome.

Fig 3-1 Donabedian’s concept.

Structure

This relates to the practice facilities, equipment, the team members, and organisation available for the provision of care.

Process

This pertains to the procedures and protocols that the dental team have to conform to so as to ensure appropriate and adequate delivery of dental services. Every activity in the dental practice is part of a process and the process itself includes an input, an action and an output – the process for instrument decontamination and sterilisation provides a good example.

Most processes are not perfect. There is generally some wasted effort, or lost time, or wastage, or miscommunication, or redoing. These problems all have costs – some small, and some great. By focusing on processes, rather than on the individuals involved in the process, we get much more rapid, substantial improvements. A good example is preparing dental materials – the properties of many dental materials are affected by measuring and mixing techniques but important aspects of the process may be omitted – usually because manufacturer’s instructions have not been followed.

Outcome

This denotes the effects of care on a patient’s dental health status. Both positive and negative outcomes should be studied to analyse the processes that led to them. Donabedian noted that: “Although outcomes might indicate good or bad care in the aggregate, they do not give an insight into the nature and location of the deficiencies or strengths to which the outcome might be attributed.”

The quality of an output is an evaluation. It is an individual’s personal judgement of some set of attributes of the output. It results from the individual’s perceptions of the output and is rooted within the individual’s personal frame of reference. It is often a relative term with no fixed unit of measurement.

This means that it is a unit-less value system and therefore can only be assessed by comparison to other similar items. The corollary to this argument is that the terms “good” and “bad” quality have no real meaning, but the terms “better” or “worse” quality do because of the comparative nature of the perception. The comparisons we make in clinical practice will be based on our past personal experiences and prejudices – those prejudices in turn and in part at least being determined by a host of external influences. From the patient’s point of view, the personal element will be expressed as an “expectation”; when positive expectations are met, quality is judged to be acceptable, and when expectations are exceeded, then quality is judged to be excellent. This is explored further in Chapter 7.

Looking at outcomes in isolation, without examining the processes that lead to them, is of limited value, but nonetheless this is what often happens in a practice. A crown does not fit and “someone” is to blame or a remake is indicated without an analysis of the “why”? The “5-why technique” of root cause analysis discussed in Risk Management in General Dental Practice is recommended here.

Outcomes should be analysed in relation to their causal antecedents. Clinical outcomes are generally regarded as falling into one or more of the following categories:

-

Functional status and wellbeing

-

Conventional physiological and biomedical measurements

-

Costs of healthcare delivery

-

Patient satisfaction with care.

The cost of unacceptable outcomes is covered in Chapter 10.

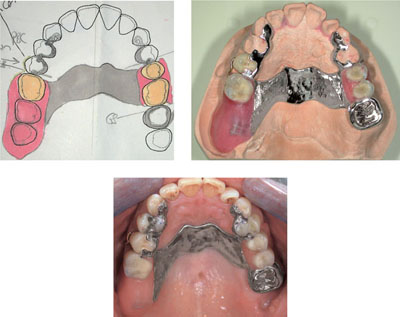

Linking Structure and Process

Structure has an impact on outcome mainly through the process of care. Each of these three dimensions can be assessed separately or in combination. The question arises whether, if structure and process are suitably addressed, the patient can be assured of a satisfactory outcome? In theory, the answer is yes. The clinical example in Fig 3-2 demonstrates the principle. If all the stages of the process are followed and the required materials are available to support these processes, the outcome is highly satisfactory. The final product is defect-free and, providing it meets or, preferably, exceeds the patient’s expectations will be perceived as a quality outcome by all the stakeholders (including the dental technician).

Fig 3-2 From design to fit: a synergy of structure and process.

In reality, we know that outcomes can be affected by patient behaviour, for which the clinician cannot always be held responsible. The progression of periodontal disease in a non- or partially-compliant patient is a good example.

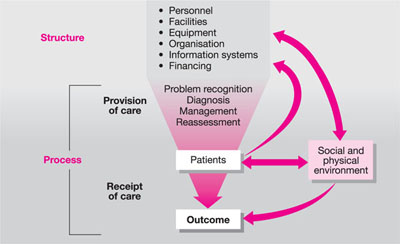

It is also true that a poor outcome does not always result every time there is an error in the provision of care. We can all cite cases of root canal therapy, which radiographically appears inadequate (for whatever reason), but which has been in situ for many years and does not appear to have compromised the long-term prognosis of the treated tooth. For this reason, it is argued that an assessment of quality should depend more on process data than on outcome data (Fig 3-3).

Fig 3-3 Relations of structure and process components in dynamics of health outcome. Modified from Starfield (1974).

A patient who attends for a tooth extraction may be the subject of a poor process which results in the successful outcome, namely the tooth has been extracted. If the process of extraction lasted 30 minutes because of misapplication of instrument/technique, an outcome measure will not identify it. If a different process had been applied, then the same outcome could have been achieved in say 10 minutes – a process measure would therefore be far more valuable in this situation. In other words, “getting there in the end” is not what quality is about.

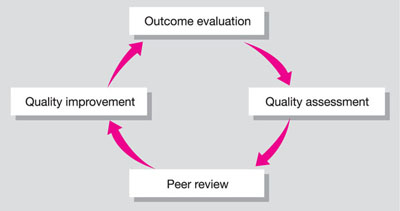

Peer Review

Aspects of the structure, process and outcomes in clinical practice are best examined amongst professional colleagues by the process of peer review. It ensures that the loop between quality assessment and quality improvement is closed and will result in improved standards of care for patients by encouraging changes in clinical practice (Fig 3-4).

Fig 3-4 Outcome assessment.

Benchmarking

The word “benchmark” was first used by the Xerox Corporation in the 1970s. The word entered the quality lexicon in 1990 when Xerox won the acclaimed Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award in 1990. It was described as: “The continuous process of measuring products, services, and practices against the company’s toughest competitors or those companies renowned as industry leaders.” We can define it as the process of identifying, understanding and adapting outstanding practices from a variety of sources to help your practice to improve its performance. It means using someone else’s successful process as a measure of desired achievement for a defined activity. It looks outward to find best practice and then measures your practice’s operations and processes against th/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses