Chapter 5

Continuous Quality Improvement

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to review the range of options available to practitioners to carry out a quality assessment with a view to embarking on a quality improvement programme.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the reader should be aware of some of the widely used methods and models that can be used for continuous quality improvement.

Introduction

Quality improvement aims to close the gap between current and expected standards of practice by identifying strengths and weakness in the systems and processes that operate within the practice.

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) theory is important in the general dental practice setting because:

-

it gives a rational definition of quality that applies in the healthcare setting

-

it clearly shows the relationship between healthcare costs and quality

-

it leads to a system under which the highest quality care can consistently be delivered at the lowest justifiable cost.

The range of quality improvement approaches includes:

-

problem solving – at individual and team level

-

process improvement

-

practice redesign and restructuring/reengineering.

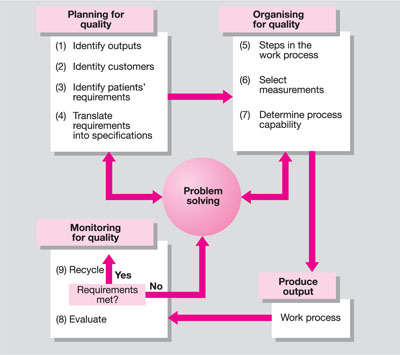

These are summarised in Fig 5-1.

Fig 5-1 The quality improvement process.

Assessment

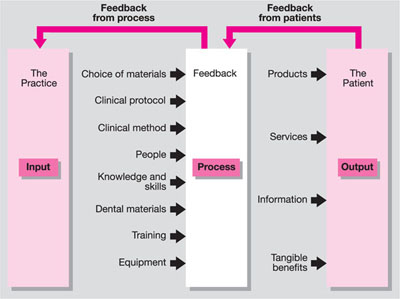

Before any improvements can be considered, a quality assessment is required, the basic elements of which are summarised in Fig 5-2.

Fig 5-2 Basic elements of a quality assessment.

Topic Selection

The topics to be assessed should be selected based on their significance, feasibility, scope for improvement, and expected results. Selecting a topic on the basis of an adverse outcome is often a good starting point.

Development of Criteria

To be reliable, valid, and reasonable, the chosen criteria must produce similar judgements when assessed by different people. In other words, two people evaluating the same data should draw the same conclusion. For this reason, the criteria must be precise and pertinent to the topic selected and based on supportive evidence; they should be looked upon as a screening device to separate acceptable and unacceptable quality.

Sources of data

Data sources include:

-

clinical records

-

direct observation of care provision

-

patient surveys

-

patient interviews.

In practice, we know that each of these data sources has its weaknesses. Incomplete or inadequate clinical records may, for example, give a misleading impression of what was actually done and said. It may be that the provision of clinical care was of a high quality but the actual note taking was inadequate. The idea “if it isn’t written down it didn’t happen” may be a lawyer’s dictum, but it is often not the whole truth. Nevertheless, the dental record is an important data source. At the very least, it should provide a chronological account of the cyclic patient care process, reflecting patient assessment, diagnosis, the treatment plan and execution, and outcome of care.

It is the chronic nature of the most common oral diseases and the repetitive documentation of them that often provides a useful insight into clinical quality. Well structured and properly kept records, together with sequential good quality radiographs, can be a reliable source for data. The use of records is further discussed later in this chapter.

Direct observation is time- and resource-consuming, but is likely to alter the behaviour of those involved in patient-practice interaction. Survey data are known to be inherently subjective and rely on accurate recall of experiences, but are nevertheless useful indicators of the patient experience.

Misconceptions

Improvements in quality are mistakenly taken to mean adding resources. The technological advances in equipment design mean that there is a plethora of gadgets and gizmos to tempt dentists and the assumption has been that adding resources would improve quality, but is this always so? Greater resources do not always ensure their proper and/or efficient use and, consequently, may not lead to improvements in quality. Does the use of Nickel-Titanium instruments and thermoplastic gutta percha injection techniques improve the clinical outcome in root canal therapy? These may speed up the process of shaping and obturation, and the less aggressive root canal preparation may reduce the risk of root fracture, but the principal determinant in endodontics success remains the efficacy of the irrigation process and the integrity of the coronal seal.

To improve clinical outcomes in endodontics may not necessarily require the structural/resource improvements (per Donabedian’s model) based on a purchase, but may simply require an evidence-based approach to root canal irrigation (see Chapter 8). This view is supported in healthcare generally where it has been shown that quality can be improved by making changes to healthcare processes, without necessarily increasing resources.

If, however, an improvement in the process is required, the addition of a resource to achieve the desired outcome would be totally justified; the use of endosonic irrigation in root canal therapy provides an excellent example.

A non-clinical example can be illustrated by one practice’s attempt to improve telephone communications with patients. In order to deal with telephone enquiries more efficiently a practice makes an investment in a new telephone system with a call waiting facility. The system is advanced and has many features. Three months after installation, there is no improvement in telephone communications. The reception staff are still unable to cope, and patients have to wait before their calls can be answered. The shortfall in quality is not the telephone system; it is a question of workload management. To improve the telephone service to patients, identify the root cause of the problem and address the processes that lead to the failure (this technique of root cause analysis was discussed more fully in an earlier volume in this series, Risk Management in General Dental Practice). The synergy created by first addressing the root cause and then adding the resource will bring about a significant improvement in quality.

Approach to Quality Improvement

All approaches to quality improvement rely on some generic principles as summarised in Fig 5-3. One simple but effective four-step process is summarised in Table 5-1. The identification may involve a problem that needs a solution, an opportunity for improvement that requires definition, or a process or system that needs to be improved.

Fig 5-3 Generic elements of quality improvement.

| 1. Identify | Ask yourself : What is the problem and how do you know that it is a problem? How frequently does it occur, or how long has it existed? What are the effects of this problem? How will we know when it is resolved? |

| 2. Analyse | The analysis takes place by asking: Who is involved or affected? Where does the problem occur? When does the problem occur? What happens when the problem occurs? Why does the problem occur? |

| 3. Develop | This uses the information from the previous stages and explores what improvements may be expected from any planned changes. A strategy for implementing the change is then developed – this will be based on the collective knowledge and experience of the team |

| 4. Test and implement | The final stage tests the effectiveness of the /> |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses