CHAPTER 3 Nonpharmacologic Management of Children’s Behaviors

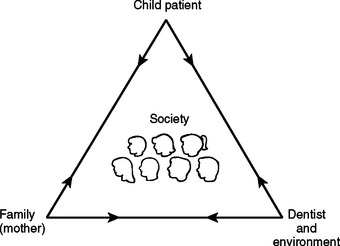

A major difference between the treatment of children and the treatment of adults is the relationship. Treating adults generally involves a one-to-one relationship, that is, a dentist-patient relationship. Treating a child, however, usually relies on a one-to-two relationship among dentist, pediatric patient, and parents or guardians. Fig. 3-1, which illustrates this relationship, is known as the pediatric dentistry treatment triangle. Recently, society has been centered in the triangle. Management methods acceptable to society and the litigiousness of society have been factorsin fluencing treatment modalities. Note that the child is at the apex of the triangle and is the focus of attention of both the family and the dental team. Although mothers’ attitudes have been shown to significantly affect their children’s behaviors in the dental office, the roles of families have been changing, and the entire family environment must be considered. Because changes are constantly occurring within each personality, one must remember that there is an ever-changing, dynamic relationship among the corners of the triangle—the child, the family, and the dental team. The arrows placed on the lines of communication also remind us that communication is reciprocal.

PEDIATRIC DENTAL PATIENTS

Over the years, numerous child development theories have evolved. Summarizing them, Alpern stated that the most important general principle concerning development is that human development is not unitary.1 He contended that there were several relatively important aspects of child development and that no single aspect could be used to assess development. He cautioned about relating to children through a single developmental label and suggested that a basic appreciation of child development knowledge could be helpful to the dentist.

Early child development study linked changes to specific chronologic ages. The initial work gathered age norms for physiologic developmental tasks. Eventually personality description principles also evolved. One of the pioneering and most notable groups, headed by Arnold Gesell, was at Yale University. Typical personality characteristics related to specific chronologic ages that have relevance to dentistry are listed in Box 3-1. These can help when developing behavioral guidance strategies. For example, if the dentist knows the limitation of a 2-year-old’s vocabulary, it becomes apparent that communication must occur through the sense of touch and voice modulation rather than through the spoken word. Recognizing also the close symbiotic relationship with parents, dentists generally try to keep the parent-child pair intact.

Box 3-1 Age-Related Psychosocial Traits and Skills for 2- to 5-Year-Old Children

Based on the work of Dr. A. Gesell.5

TWO YEARS

Geared to gross motor skills, such as running and jumping

Relating physical changes to specific chronologic ages led to the establishment of developmental milestones that became a means of assessing individual children. Classic developmental milestones are listed in Table 3-1. From these milestones, ranging from infancy through early childhood, two pieces of information are derived: (1) the average age at which a child acquires particular skills and (2) the normal range of ages at which a skill is acquired. A general principle is that, the earlier a skill emerges, the narrower is the range. On the other hand, developmental tasks tend to occur with wider ranges of normality as age increases. For the dentist, this holds practical importance. For example, consider the task of teaching children how to floss their teeth. Because the ability to floss occurs later in life (9 to 12 years of age), there is a wide performance range. Knowing the general developmental principle reminds the clinician to consider the ability or readiness of the individual to perform a given task.

Table 3-1 Average Age and Age Range of Selected Physical Developmental Milestones

| Developmental Task | Average Age | Normal Age Range |

|---|---|---|

| Focuses on light | 2 wk | 1 to 4 wk |

| Lies on stomach, lifts chin | 3 wk | 1 to 10 wk |

| Birth weight doubles | 6 mo | 5 to 7 mo |

| Rolls from back to stomach | 7 mo | 5½ to 11 mo |

| Sits alone | 7 mo | 6 to 11 mo |

| Stands with support | 10 mo | 7½ to 14 mo |

| Stands alone | 13½ mo | 9 to 18 mo |

| Walks alone | 14 mo | 10 to 20 mo |

| Bowel control attained | 18 mo | 1 to 2½ yr |

| First menstruates | 12 yr, 9 mo | 10 to 17 yr |

Another area that has received great attention from psychologists is the socialization of children. As with physical development, age-specific skills have been derived for social development; these take into account both interpersonal relationships and independent functioning skills. Some of the key personality characteristics are identified in Box 3-1.

Intellectual development is probably the area most comprehensively studied, beginning in the early 1900s with the work of Alfred Binet.2 The method that he employed quantified mental abilities in relation to chronologic age. It led to the concept of the IQ (intelligence quotient), which was measured by tasks examining memory, spatial relationships, reasoning, and a variety of other primary mental skills. By determining the average age required to pass each task, he derived age norms. This enabled an examiner to determine a child’s mental age based on performance. For health care providers, viewing children in terms of their mental ages can be a helpful approach.

The IQ formula used by Binet follows:

It is those individuals with intelligence deficiency that concern the dentist because they may require special behavior guidance. Four degrees of severity of mental retardation are specified according to the level of intellectual impairment (and with the proviso of a deficit in adaptive functioning).3 They are listed in Table 3-2.

Table 3-2 Degrees of Severity of Mental Retardation

| Mild mental retardation | IQ level 50-55 to approximately 70 |

|---|---|

| Moderate retardation | IQ level 35-40 to 50-55 |

| Severe mental retardation | IQ level 20-25 to 35-40 |

| Profound mental retardation | IQ level 20 or 25 |

From American Psychiatric Association, DSM-IV.3

Severe Mental Retardation:

About 3% to 4% of people with mental retardation may be severely retarded. As adults, they may be able to perform simple tasks in supported settings and can adapt well to life in the community, such as a group home or family environment unless they have a complicating associated handicap requiring special care.

Profound Mental Retardation:

The environment is such a crucial factor in the development of a human being that it can be discussed as an independent factor only on the theoretic level. The fact that each child appears to have a characteristic temperament from his or her earliest age has been suggested by Sigmund Freud and by Gesell and Ilg.4,5 In recent years, however, some psychiatrists and psychologists have emphasized the influence of the child’s early environment when discussing the origin of human personality. Whether personality is developed by “nature” (genetic influence) or “nurture” (environmental influence) is an age-old, unresolved question. However, if these two influences are in harmony, healthy development of the child can be expected; if they are dissonant, behavioral problems are almost sure to ensue.

VARIABLES INFLUENCING CHILDREN’S DENTAL BEHAVIORS

The responses of children to the dental environment are diverse and complex. Children present for treatment with differences in age, maturity, temperament, experience, family background, culture, and oral health status. Klingberg and Broberg,6 in a review of literature from 1982 to 2006, reported dental fear/anxiety and dental behavior management problems were relatively common for pediatric dental patients, each affecting 9% of children and adolescents. Girls exhibited more dental anxiety and dental behavior management problems than did boys. Dental fear/anxiety was more closely associated with temperamental traits such as shyness, inhibition, and negative emotionality, whereas behavioral problems were connected with activity and impulsivity.

Dental fear/anxiety is not synonymous with dental behavior management problems. In a study of more than 3200 Swedish children, Klingberg and Berggren7 found that 27% of patients with dental behavior management problems showed dental fear and anxiety, whereas 61% of those with fear/anxiety reacted with behavioral problems. The key to successful outcomes (ie, compliance, relief of anxiety, completion of quality care, development of trusting relationship) is appropriately assessing the child and family to prepare them to actively participate in a positive manner in the child’s oral health care. Dentistry has had some difficulty identifying the stimuli that lead to misbehavior in the dental office, although several variables in children’s backgrounds have been related to it.

General Behavior Problems

Klingberg and Broberg6 found some support for a relationship between general behavioral problems and dental behavior management problems. Children who have difficulty focusing attention and or adjusting activities to their general environment have increased problems complying with behavioral expectations in the dental environment. General fears can be important etiologic factors in development of dental fears. Some children, however, have behavioral problems only in the dental environment; this may be due to previous negative experiences with dental care.

CLASSIFYING CHILDREN’S COOPERATIVE BEHAVIOR

Wright’s clinical classification places children in three categories8:

Another system, which has been used in behavioral science research, is referred to as the Frankl Behavioral Rating Scale.9 The scale divides observed behavior into four categories, ranging from definitely positive to definitely negative. Following is a description of the scale:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses