3 Indications and Contraindications

The placement of immediate dental implants can provide a similar success/survival outcome as that of early and delayed placement protocols, as long as attention is given to several critical guidelines (Chen, Wilson, et al. 2004; Wagenberg and Froum 2006; Chen, Beagle, et al. 2009). These guidelines can be considered as indications and contraindications for immediate placement and are represented by a number of clinical and anatomic challenges with which the patient may present.

As previously discussed in the chapter concerning risk assessment, a number of local factors involving dental and anatomic issues must be assessed before surgical placement of immediate dental implants (Chen and Buser 2009). Failure of the dentist to thoroughly address these localized issues may result in an outcome that is deemed unsatisfactory with regards to esthetics or function and may prevent the implant from achieving osseointegration (Figure 3.1). Quite often, both the dentist and the patient become too focused on replacing a failing tooth with an immediate implant to accelerate the treatment process, only to arrive at the endpoint with an unforeseen complication that could have been avoided with a better understanding of the treatment complexities (Chen and Buser 2009). This chapter will focus on the local risk factors commonly encountered with the surgical placement of immediate dental implants.

Figure 3.1 Unsatisfactory esthetics with tooth #9 implant.

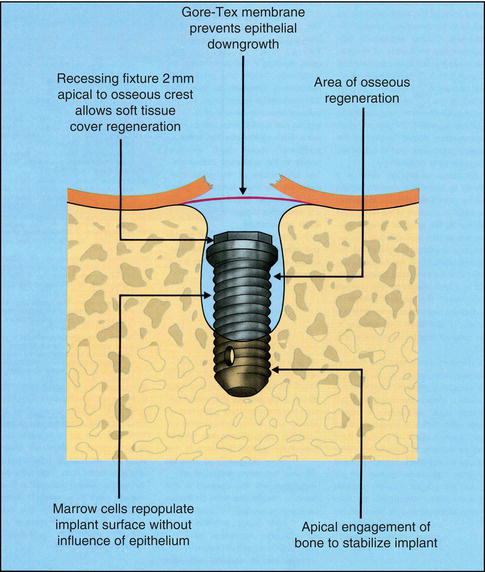

Figure 3.2 Original diagram of immediate placement protocol. From Lazzara 1989. Courtesy of Quintessence Publishing.

PRIMARY STABILITY

Along with proper restoratively driven positioning, the ability to achieve primary mechanical stability with an immediately placed dental implant is paramount (Figure 3.2) (Lazzara 1989). Often this requires the implant to engage bone along the lateral walls of the socket without changing the original socket depth, or by engaging bone apical to the original socket dimensions. In either of these situations, only one to three threads of the implant need to be in contact with the osteotomy site. An implant that can be moved laterally with finger pressure following placement will have a poor chance of achieving osseointegration and should be aborted. Care should be exercised to follow the manufacturer’s preparation guidelines, as an undersized osteotomy may result in compression necrosis of the bone, thus causing implant failure to occur (Figures 3.3–3.5). This is especially true with the use of tapered designed implants when the primary stability is developed at the crest, rather than apically or laterally. Another frequent mishap in an effort to achieve primary stability is choosing an implant with a restorative platform too large for the planned restoration, only because the larger implant diameter is able to achieve stability. Not only is this a concern for esthetics, but a larger implant diameter may not provide sufficient space between the implant surface and the buccal plate (horizontal defect dimension, or HDD) to allow a blood clot to form or bone graft to be placed, and will therefore contribute to compression along the buccal plate of bone (Figure 3.6) (Buser, Martin, et al. 2004; Araujo, Wennstrom, et al. 2006).

Figure 3.3 Occlusal view of bone loss caused by compression necrosis.

Figure 3.4 Buccal view of bone loss caused by compression necrosis.

Figure 3.5 Lateral view of bone loss caused by compression necrosis.

Figure 3.6 Loss of buccal plate caused by selecting improper implant diameter.

INFERIOR ALVEOLAR NERVE

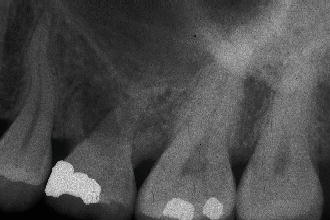

As with early and delayed placement, it is important to precisely locate the position of the inferior alveolar nerve, or the mental foramen, radiographically when placing an immediate implant in the posterior mandible. Many guidelines have been established that alert the clinician to stay at least 2 mm superior to the inferior alveolar nerve during the osteotomy and placement of the implant (Buser, von Arx, et al. 2000). Mandibular second premolar sites frequently have their apex near the mental foramen and also have a wide socket morphology requiring a 4.8 mm implant diameter for stability (Figure 3.7). In some instances, it may be best to proceed with an early placement protocol, rather than immediate, for these situations where there is risk in injury to the nerve in an attempt to achieve primary stability.

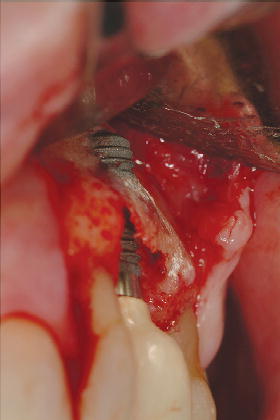

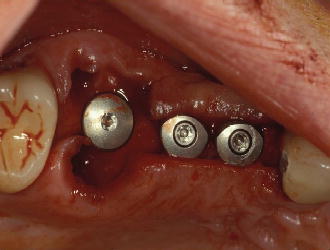

The variability of root morphology for mandibular first and second molars makes immediate implant placement in these sites unpredictable. One should avoid the temptation to place the implant into the mesial or distal root socket to achieve stability, only to have an implant that results in poor positioning from a restorative perspective. It is often best to proceed with a 12-week healing period following the extraction of a mandibular molar before implant placement is performed (Chen, Wilson, et al. 2004). If an immediate molar implant can be placed, grafting the HDD with an osseous graft and use of a bioresorbable membrane will be required (Fugazzotto 2008a, 2008b), and a healing time to achieve osseointegration may exceed 16 weeks (Figures 3.8 and 3.9).

Figure 3.7 Radiograph of tooth #29 treated with immediate placement using a 4.8 mm diameter implant.

Figure 3.8 Occlusal view of tooth #3 following extraction and osteotomy preparation.

Figure 3.9 Occlusal view of tooth #3 following immediate placement.

Figure 3.10 Radiograph of deciduous tooth K and the proximity to the maxillary sinus floor.

Figure 3.11 Radiograph of 12 weeks of healing following the extraction of tooth K.

Figure 3.12 Radiograph of implant placed into the deciduous tooth K site in conjunction with a simultaneous osteotomy sinus lift and bone graft.

MAXILLARY SINUS

The maxillary sinus position may pose concerns when placing an immediate implant into the second premolar or first and second molar sites (Fugazzotto and De 2002). At times the second premolar site is circumferentially wide and primary stability cannot be achieved using a 4.8 mm diameter implant to engage the lateral walls of the socket. In these instances, an early placement protocol is desired to reduce the socket dimensions and provide stability and predictability (Figures 3.10–3.12). Similar to mandibular molar sites, it is desirable not to place a maxillary implant into the mesial-buccal, distal-buccal, or palatal root areas to gain primary stability, only to have an implant positioned poorly from a restorative perspective. Certainly, if adequate bone height is available in maxillary molar sites without penetration into the sinus, an immediate implant can be inserted, but these circumstances do not occur frequently.

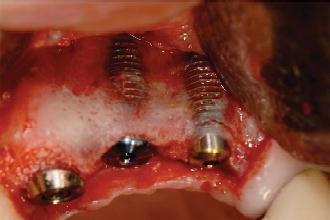

SITES REQUIRING GUIDED BONE REGENERATION

Sites affected by trauma or infection may demonstrate significant loss in the buccal or lingual boney plates, thus exposing a significant amount of implant surface upon immediate placement. Although primary stability can be achieved, it is best to initiate guided bone regeneration (GBR) to reconstruct the alveolar ridge to improve success and optimize esthetics, especially in the anterior region (Figures 3.13 and 3.14) (Buser, Dula, et al. 1993; Buser, Bornstein, et al. 2008; Buser, Chen, et al. 2008). The predictability of GBR is well supported in the literature using autogenous bone grafts, bone morphogenic protein (BMP), or bone allografts in conjunction with membranes or titanium mesh for this indication (Buser, Dahlin, et al. 1994).

Figure 3.13 Occlusal view of #9 site requiring GBR.

Figure 3.14 Occlusal view of #9 site following GBR.

RETAINED DECIDUOUS TEETH

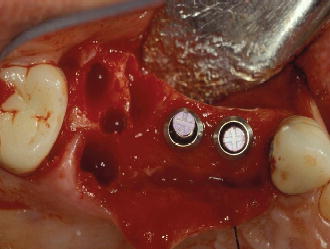

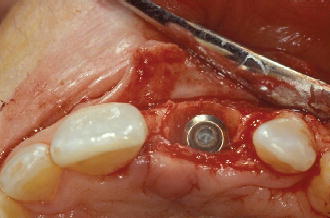

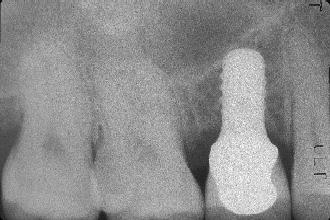

Retained deciduous teeth with a congenitally missing permanent tooth are often good candidates for an immediately placed implant (de Oliveira, Macedo, et al. 2009; Borzabadi-Farahani 2011). Frequently seen clinically is the absence of a maxillary or mandibular second premolar, with the retained deciduous molar in place (Figures 3.15–3.18). When detected early, these sites can be developed orthodontically to achieve the ideal mesial-distal dimension of the congenitally absent tooth prior to extraction. Following the cessation of alveolar jaw growth, the deciduous tooth can be removed and the implant inserted, assuming the anatomical structures (alveolar nerve/sinus) are not at risk. Generally, adequate bone is available for primary implant stability to be achieved, even if the roots of the deciduous tooth are not fully resorbed. Minimal bone grafting and use of a resorbable membrane may be desired if an osseous defect is present in the residual root sockets, adjacent to the implant surface.

NON-RESTORABLE CARIOUS TEETH

Figure 3.15 Buccal view of retained deciduous tooth A.

Figure 3.16 Radiograph of retained deciduous tooth A.

Figure 3.17 Occlusal view of immediate implant replacing deciduous tooth A.

Figure 3.18 Final radiograph of immediate implant replacing deciduous tooth A.

Until recently, a periodontal crown-lengthening procedure or orthodontic extrusion was the primary treatment option available for teeth having significant subgingival caries (Rosenberg, Garber, et al. 1980; Sabri 1989). While both options are predictable, they result in />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses