Chapter 3

Hypertension

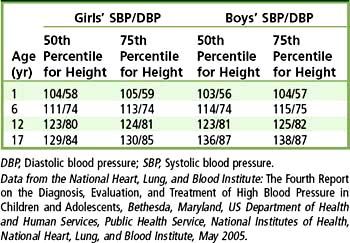

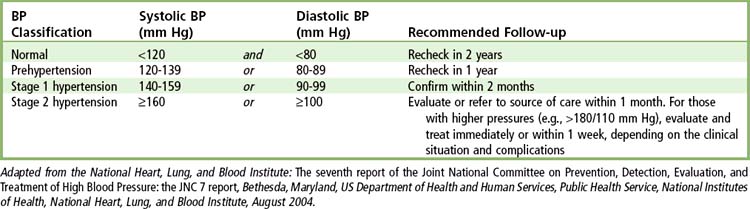

Hypertension is an abnormal elevation in arterial pressure that can be fatal if sustained and untreated. People with hypertension may not display clinical signs or symptoms for many years but eventually can experience symptomatic damage to several target organs, including kidneys, heart, brain, and eyes. In adults, a sustained systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or a sustained diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater is defined as hypertension. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) provided several revisions to the previous 1997 report< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />1 (Table 3-1). These guidelines include an updated classification that redefines “normal” blood pressure as 120/80 mm Hg and introduces a new category of “prehypertension” (systolic blood pressures ranging from 120 to 139 and diastolic pressures ranging from 80 to 89 mm Hg), which encompasses the previously designated categories of “normal” and “borderline” hypertension. This revision reflects the findings that health risks are increased with blood pressures higher than 115/75 mm Hg and that lowering blood pressure in patients with what was formerly considered “normal” or “borderline” blood pressure can result in decreased frequency of adverse vascular events such as stroke and myocardial infarction (MI). In addition, the previously designated stages 2 and 3 of hypertension were combined into a single stage 2 category, because treatment for both groups is essentially the same. Table 3-1 also includes recommendations for follow-up care based on initial blood pressure measurements. A separate publication provides similar information on the classification, detection, diagnosis, and management of hypertension in children and adolescents, while updating 1996 guidelines.2 In children and adolescents, hypertension is defined as elevated blood pressure that persists on repeated measurement at the 95th percentile or greater for age, height, and gender (Tables 3-2 and 3-3). For example, according to Table 3-3, a 6-year-old girl who is at the 50th percentile in height would be considered to have hypertension if her blood pressure was persistently 111/74 mm Hg or greater.

TABLE 3-2 Classification of Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents

| Classification |

SBP or DBP Percentile* |

| Normal |

<90th |

| Prehypertension |

90th to <95th, or pressure exceeds 120/80 even with <90th percentile up to <95th percentile |

| Stage 1 hypertension |

95th to 99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg |

| Stage 2 hypertension |

>99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg |

DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; SBP, Systolic blood pressure.

Data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents, Bethesda, Maryland, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, May 2005.

The dental health professional can play a significant role in the detection and control of hypertension and may well be the first to detect a patient with an elevation in blood pressure or with symptoms of hypertensive disease. Along with detection, monitoring is an equally valuable service, because patients who are receiving treatment for hypertension may nevertheless fail to achieve adequate control because of poor compliance or inappropriate drug selection or dosing. The JNC 7 specifically encourages the active participation of all health care professionals in the detection of hypertension and the surveillance of treatment compliance.1 Only a physician can make the diagnosis of hypertension and decide on its treatment. The dentist, however, should detect abnormal blood pressure measurements, which then become the basis for referral to or consultation with a physician.

Management of the dental patient with hypertension poses several potentially significant considerations. These include identification of disease, monitoring, stress and anxiety reduction, prevention of drug interactions, and awareness and management of adverse drug side effects.

Of note, new guidelines (JNC 8) are currently under review and scheduled to be published in 2012.

General Description

Prevalence

With 35 million office visits annually, hypertension is the most common primary diagnosis in America.1 Before 1990, the prevalence of hypertension was steadily declining; however, recent evidence indicates that the trend has reversed, and hypertension is once again on the rise.3 According to National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data for the period 1999 to 2000, at least 65 million adults in the United States have high blood pressure (HBP) or are taking antihypertensive medication.4 This estimate equals about one fourth of the population and represents a 30% increase from 1988 to 1994.5 In a typical practice population of 2000 patients, therefore, around 500 will have hypertension. This marked increase is attributed to aging of the population and to the epidemic increase in obesity. The National High Blood Pressure Education Program was begun in 1972, and in a little more than 3 decades, it has had significant success.1 The number of people with HBP who are aware of their condition has increased from 51% to 70%, and the percentage of those receiving treatment for HBP has increased from 31% to 59%. The proportion of patients taking medication whose blood pressure is controlled to 140/90 increased from 10% to 34% during the same period. Concomitant with increased awareness and treatment has been a significant decline in number of deaths from coronary heart disease (50%) and from stroke (57%), although this decline has slowed in recent years.1 Although these trends are encouraging, 30% of patients with HBP remain unaware of their disease, 40% of patients with HBP are not being treated, and more than 60% of hypertensive patients are taking medications but have not achieved adequate control of the condition.

Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension were once based largely on diastolic blood pressure; with growing recognition of the importance of systolic blood pressure, however, this is no longer the case. Isolated systolic hypertension gradually increases with age such that among patients older than 50 years of age, it is the most prevalent form of hypertension.

The prevalence of high blood pressure increases with aging, such that more than half of all Americans aged 65 and older have hypertension.6 If people live long enough, more than 90% will develop hypertension.7 Systolic blood pressure continues to rise throughout life, but diastolic blood pressure rises until around age 50 and then levels off or falls; as a result, after the age of 50, isolated systolic hypertension becomes the more prevalent pattern. In one study, isolated systolic hypertension was identified in 87% of inadequately controlled patients older than 60 years of age.8 Isolated diastolic hypertension most commonly is seen before age 50. Diastolic blood pressure is a more potent cardiovascular risk factor than is systolic blood pressure until age 50; thereafter, systolic blood pressure is more important.9

Prevalence varies with race as well and is highest among African Americans. In general, it is lower among Hispanics than among whites; however, variation has been noted among racial subgroups. For example, the prevalence of hypertension among Mexican Americans is lower than among non-Hispanic whites, although among Puerto Rican Americans, it is higher.10 Prevalence generally is higher in Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Native Alaskans than in whites; however, again, variation is seen among subgroups.11

Etiology

About 90% of patients have no readily identifiable cause for their disease, which is referred to as primary (essential) hypertension. In the remaining 10% of patients, an underlying cause or condition may be identified; for these patients, the term secondary hypertension is applied. Box 3-1 is a listing of the most common identifiable causes of secondary hypertension. Lifestyle can play an important role in the severity and progression of hypertension; obesity, excessive alcohol intake, excessive dietary sodium, and physical inactivity are significant contributing factors.

Box 3-1

Identifiable Causes of Hypertension

• Sleep apnea

• Drug-induced or drug-related

• Chronic kidney disease

• Primary aldosteronism

• Renovascular disease

• Chronic steroid therapy and Cushing syndrome

• Pheochromocytoma

• Coarctation of the aorta

• Thyroid or parathyroid disease

Data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report, Bethesda, Maryland, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, August 2004.

Pathophysiology and Complications

In primary hypertension, the basic underlying defect is a failure in the regulation of vascular resistance. The pulsating force is modified by the degree of elasticity of the walls of larger arteries and the resistance of the arteriolar bed. Control of vascular resistance is multifactorial, and abnormalities may exist in one or more areas. Mechanisms of control include neural reflexes and ongoing maintenance of sympathetic vasomotor tone and other effects mediated by neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, extracellular fluid, and sodium stores; the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pressor system; and locally active hormones and substances such as prostaglandins, kinins, adenosine, and hydrogen ions (H+). In isolated systolic hypertension, which commonly is seen in elderly persons, the underlying problem is one of central arterial stiffness and loss of elasticity.7

Many physiologic factors may have an effect on blood pressure. Increased viscosity of the blood (e.g., polycythemia) may cause an elevation in blood pressure resulting from an increase in resistance to flow. A decrease in blood volume or tissue fluid volume (e.g., anemia, hemorrhage) reduces blood pressure. Conversely, an increase in blood volume or tissue fluid volume (e.g., sodium/fluid retention) increases blood pressure. Increases in cardiac output associated with exercise, fever, or thyrotoxicosis also may increase blood pressure.

A linear relationship exists between blood pressures at any level above normal and an increase in morbidity and mortality rates from stroke and coronary heart disease. Blood pressures above 115 mm Hg systolic and 75 mm Hg diastolic are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.12 It is estimated that about 15% of all blood pressure–related deaths from coronary heart disease occur in persons with blood pressure in the prehypertensive range.13 However, the higher the blood pressure, the greater the chances of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and kidney disease. For every increase in blood pressure of 20 mm Hg systolic and 10 mm Hg diastolic, a doubling of mortality related to ischemic heart disease and stroke occurs.1 Hypertension precedes the onset of vascular changes in the kidney, heart, brain, and retina that lead to such clinical complications as renal failure, stroke, coronary insufficiency, MI, congestive heart failure, dementia, encephalopathy, and blindness. If the condition goes untreated, about 50% of hypertensive patients die of coronary heart disease or congestive heart failure, about 33% of stroke, and 10% to 15% of renal failure.14

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Hypertension may remain an asymptomatic disease for many years, with the only sign being an elevated blood pressure. Blood pressure is measured with the use of a sphygmomanometer (Figure 3-1). Pressure at the peak of ventricular contraction is the systolic pressure. Diastolic pressure represents the total resting resistance in the arterial system after passage of the pulsating force produced by contraction of the left ventricle. The difference between diastolic and systolic pressures is called pulse pressure. Mean arterial pressure is roughly defined as the sum of the diastolic pressure plus one-third the pulse pressure. Patients commonly are found to have significant variability in blood pressures. Labile hypertension is the term that was previously used to describe the status of a subgroup of patients with wide variability in blood pressure readings; however, this term has fallen into disuse because it is now recognized that variability in blood pressure is the norm rather than the exception. About 15% to 20% of patients with untreated stage 1 hypertension have what is called white coat hypertension, which is defined as persistently elevated blood pressure only in the presence of a health care worker but not elsewhere.6 In these patients, accurate blood pressure readings may require self-measurement at home or 24-hour ambulatory monitoring. Persons with blood pressure elevation in this setting are at lower risk for hypertensive complications than are those with sustained hypertension.

Before the age of 50, hypertension typically is characterized by an elevation in both diastolic and systolic pressures. Isolated diastolic hypertension, defined as a systolic pressure of 140 or less and a diastolic pressure of 90 or greater, is uncommon and most often is found in younger adults. Although the prognostic significance of this condition remains unclear and controversial, it appears that it may be relatively benign.15 Isolated systolic hypertension is defined as a systolic pressure of 140 or higher and a diastolic blood pressure of 90 or less; it generally is found in older patients and constitutes an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Occasionally, isolated systolic blood pressure elevation is found in older children and young adults, often male. In these age groups, this form of hypertension is due to the combination of rapid growth in height and very elastic arteries, which accentuate the normal amplification of the pressure wave between the aorta and the brachial artery, resulting in high systolic pressure in the brachial artery but normal systolic pressure in the aorta.6

The earliest sign of hypertension is an elevated blood pressure reading; however, funduscopic examination of the retina may show early changes of hypertension consisting of narrowed arterioles with sclerosis. As indicated earlier, hypertension may remain an asymptomatic disease for many years, but when symptoms do occur, they include headache, tinnitus, and dizziness. These symptoms are not specific for hypertension, however, and may be experienced just as commonly by normotensive persons.14

Late signs and symptoms are related to involvement of various target organs, including kidney, brain, heart, or eye (Box 3-2). In advanced cases, retinal vessel hemorrhage, exudate, and papilledema may occur and are indicative of accelerated malignant hypertension, which is a medical emergency and requires immediate intervention. Hypertensive encephalopathy is characterized by headache, irritability, alterations in consciousness, and other signs of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction. Other findings in advanced cases may include enlargement of the left ventricle with impairment of cardiac function, leading to congestive heart failure. Renal involvement can result in hematuria, proteinuria, and renal failure. Persons with hypertension may report fatigue and coldness in the legs, resulting from the peripheral arterial changes that may occur in advanced hypertension. Patients with hypertension often demonstrate an accelerated cognitive decline with aging.16 Although these changes may be seen in patients with both primary and secondary hypertension, additional signs or symptoms may be present in secondary hypertension associated with underlying disease.

Box 3-2 Signs and Symptoms of Hypertensive Disease

Early

• Elevated blood pressure readings

• Narrowing and sclerosis of retinal arterioles

• Headache

• Dizziness

• Tinnitus

Advanced

• Rupture and hemorrhage of retinal arterioles

• Papilledema

• Left ventricular hypertrophy

• Proteinuria

• Congestive heart failure

• Angina pectoris

• Renal failure

• Dementia

• Encephalopathy

Laboratory Findings

The JNC 71 recommends that patients who have sustained hypertension be screened through routine laboratory tests, including 12-lead electrocardiogram, urinalysis, blood glucose, hematocrit, and a serum potassium, creatinine, calcium, and lipid profile. Results of these tests serve as baseline laboratory values that the physician should obtain before initiating therapy. Additional tests should be ordered if clinical and laboratory findings suggest the presence of an underlying cause for hypertension.

Medical Management

Evaluation of a patient with hypertension includes a thorough medical history, a complete physical examination, and routine laboratory tests as described earlier. Additional diagnostic tests or procedures may be performed to detect secondary causes of hypertension or to make a definitive diagnosis. Patients found to have an identifiable cause for their hypertension should be treated for that disorder. Those without an identifiable cause are diagnosed with primary hypertension.

Classification and diagnosis of blood pressure (see Table 3-1) are based on an average of two or more properly measured blood pressure readings obtained in the seated patient on each of two or more office visits.1 Measurement of blood pressure most commonly is achieved using the auscultatory method with a mercury, aneroid, or hybrid sphygmomanometer (see Figure 3-1). Mercury sphygmomanometers have long been considered the most accurate of such devices and the “gold standard;” however, because of increasing environmental concerns about mercury and the risk of breakage and spill, their use has become limited. Aneroid digital devices are the type most commonly used in dental offices. They are easy to use and provide reasonably accurate readings; however, they require regular calibration, and at least two readings should be taken.17

Patients with a diagnosis of prehypertension are not usually candidates for drug therapy but rather are encouraged to adopt lifestyle modifications to decrease their risk of developing the disease. Prehypertension is not a disease but rather a designation that reflects the fact that these patients are at increased risk for the development of hypertension. Lifestyle modifications include losing weight; adopting a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and low-fat dairy products; reducing intake of foods high in cholesterol and saturated fats; decreasing sodium intake; limiting alcohol intake; and engaging in daily aerobic physical activity (Box 3-3). It is considered essential that patients with prehypertension, as well as those with diagnosed hypertension, follow these recommendations, because lifestyle modifications have been shown to effectively reduce blood pressure, prevent or delay the incidence of hypertension, enhance antihypertensive drug therapy, and decrease cardiov/>

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue