Factors Involved in Single Implants

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

. Describe the classification of the various areas of the oral cavity for the placement of single implant placement.

. Describe the classification of the various areas of the oral cavity for the placement of single implant placement.

. Explain osseous considerations.

. Explain osseous considerations.

. Understand soft tissue considerations.

. Understand soft tissue considerations.

. Explain the different types and shapes of implants.

. Explain the different types and shapes of implants.

. Understand surgical techniques of implant placement in esthetic and nonesthetic zones.

. Understand surgical techniques of implant placement in esthetic and nonesthetic zones.

Osseous Considerations

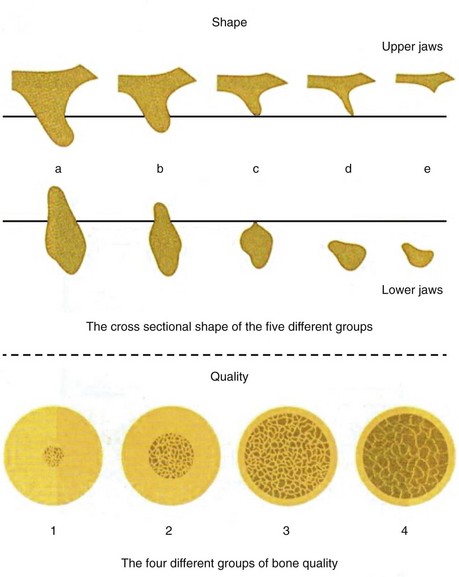

The fact that the process of bone resorption slows down after tooth extraction has been well-established. The amount of bone resorbed during the first year after tooth extraction is much greater than that during the following years.1 A complex osseous situation exists when bone volume is diminished and the quality of bone is not uniform in different regions of the jaws. These two important factors, the quality and quantity of bone, play an important role in determining implant location and position. In 1985, Zarb and Lekholm created classification systems for the quality and quantity of jaw bones. They classified bone quality as type I to type IV and bone quantity as type A to type E (Figure 3-1).

If the remaining bone in the buccal aspect of the implant is less than 1 mm, the area should be reinforced with the guided bone regeneration (GBR) technique. This is more important in the anterior areas of the maxilla, because a thin buccal bone in this area leads to resorption of bone and subsequent gingival recession and exposure of the metallic margin of the implant, compromising the patient’s esthetic appearance. To prevent such problems, all surgeries for single implants in the anterior area of the maxilla should be augmented with bone.2

Soft Tissue Considerations

Similar to bone, which is an important determining factor for the long-term maintenance and success of an implant, keratinized soft tissue around the implant can play an important role in the longevity of the implant and in prevention of peri-implantitis. Considerable research has been dedicated to this issue. Some studies have shown that implants are durable even without keratinized gingiva, and no problems are encountered. Other studies have emphasized that attached keratinized gingiva is favorable and in fact necessary for implants.3 Therefore, to prevent subsequent problems, the logical course is to provide an environment for implant placement in which sufficient keratinized gingiva is present. This environment can be provided during implant placement or subsequent to it. Some advantages of keratinized gingiva around implants are noted in Box 3-1.

During treatment planning for placement of implants, the presence of attached keratinized gingiva, which is very important, should be taken into account. This gingiva should be reconstructed during implant placement or after it if no keratinized gingiva is present. It has been empirically shown that at least 2 mm of attached keratinized gingiva around an implant is sufficient, and the prognosis improves with an increase to more than 2 mm. However, some authors believe that the need for keratinized gingiva is patient specific.4 Therefore, during treatment planning, the amount of attached keratinized gingiva can be measured. If insufficient keratinized gingiva is present, measures can be taken to provide it. If sufficient keratinized gingiva is present, plans should be made so that this gingiva is located in its proper place around the implant.

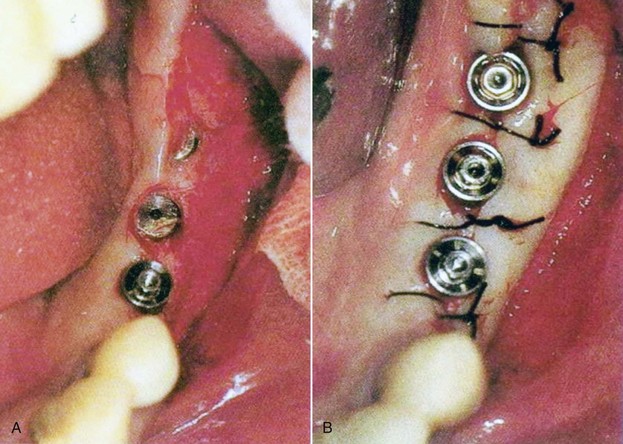

Apically Positioned Flap

The apically positioned flap is commonly used in the maxilla, because the palate is predominantly covered with keratinized gingiva. When attached gingiva on the buccal aspect of the implant is insufficient, a palatally inclined incision can be used to direct some keratinized gingiva from the palatal side to the buccal side. In the mandible, if the amount of keratinized gingiva is sufficient on the lingual aspect, the same procedure can be carried out (Figure 3-2).

Free Gingival Graft

The free gingival graft was introduced by Bjorn in 1963. For this graft, a split-thickness flap is made in the recipient site at the mucogingival junction (MGL). The periosteum is preserved on the bone, and a segment of the keratinized mucous membrane, approximately the size of the recipient site, is removed from the palatal mucosa or the edentulous ridge and placed in the recipient site (Figure 3-3). The success of this technique has been reported to be very high in the attached keratinized gingiva.

Implant Configuration

Bone-Level Implants

With bone-level implants, the platform is placed at the level of the jaw bones. These implants are used in the regions of the esthetic zone; they are placed deep into bone so that no metallic surfaces are visible (Figure 3-4). Current changes in implant surfaces and microthreads on the upper areas adjacent to the bone have resulted in assumptions that crestal bone may be more stable (Figure 3-5).

Figure 3-4 Two types of bone-level implants.

Figure 3-5 Implant with microthreads on top.

Tissue-Level Implants

Tissue-level implants usually have a collar with a smooth titanium surface (Figure 3-6). The platforms of the implants are usually located 1.5 to 3 mm above the bone level, and the titanium collar is a proper location for the attachment of the gingival soft tissue. An advantage of these implants is a decrease in resorption of bone at the crest, because formation of the biologic width does not require resorption of the crestal bone. A disadvantage of these implants is the visibility of the metallic collar of the implant, resulting in an unesthetic appearance when the gingival tissue is thin. However, because the posterior regions of both arches are not located in the esthetic zone and are not visible during speaking and smiling, these implants can be used in the nonesthetic zone.

Figure 3-6 Two types of tissue-level implants.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses