3

Basic Procedures in Physical Examination

Time-tested basic procedures in physical examination include inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation, olfaction, and evaluation of function. The process begins the moment the patient presents for care. Note general appearance, body language, and mannerisms, as these are reliable indicators of the patient’s physical and mental state. When shaking the patient’s hand, does the patient respond in kind? A patient who shuns a handshake may be doing so for cultural reasons, or the handshake may be painful, as for a patient suffering from arthritis. Does the patient maintain or avoid eye contact when spoken to? Reticence to maintain eye contact and poor personal hygiene may indicate depression or some other psychological disorder.

Establish the patient’s level of consciousness, cognitive function, and language comprehension within the first minute or 2 of contact with the patient. When the patient speaks, note voice quality. Abnormalities in volume may indicate hearing loss, while hoarseness may be due to laryngeal pathoses. Peculiarities of speech such as an unusual accent or pattern of communication, slurring, dysphasia, aphasia, garbled speech, or lapses of speech may be consequential observations.

Inspection

Inspection is defined as the process of examination that relies on the sense of vision. It is not only the most common but often the most successful examination technique.

Note the patient’s physical characteristics, that is, anatomical architecture, mobility, gait, color, and respiratory function. Alterations in body size, shape, and symmetry may suggest developmental or acquired abnormalities. Mobility, gait, and postural abnormalities may indicate skeletal or neuromuscular defects. Pallor may be an indicator of anemia, while cyanosis may indicate problems associated with the respiratory and/or cardiovascular system. Jaundice may be a sign of hemolytic anemia, liver disease, or a pancreatic abnormality. Evidence of respiratory difficulty may be associated with allergic, pulmonary, or cardiac disorders.

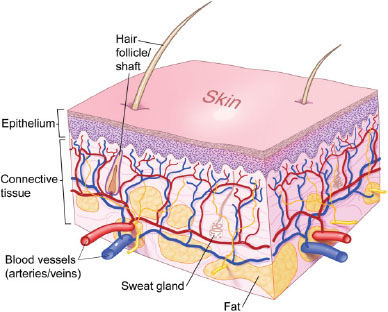

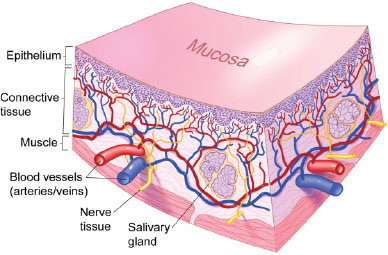

Once global inspection of the patient is accomplished, the clinician should proceed to the more focused inspection of specific tissues such as visible skin and the oral mucosa. The skin (Figure 3.1) and oral mucosa (Figure 3.2) are metabolically active tissues. Both serve a primary protective function for the body, and through their rich neural and vascular supply mediate sensory contact with the environment and help regulate temperature.

To the uninitiated, many skin and mucosal lesions may look alike, but most have characteristic primary presentations. These primary lesions often progress to form well-defined secondary lesions as a consequence of such factors as normal maturation, trauma, therapy, or secondary infection. For example, a lip lesion may begin as a vesicle, but may quickly break down to form an erosion or ulcer and eventually crust as healing occurs. There is often a dynamic spectrum of coexisting primary and secondary lesions.

Careful inspection of the skin and oral mucosa may reveal the first signs of internal or systemic disease and, on occasion, skin lesions may provide the first clues essential for the diagnosis of certain oral conditions. Note changes in color (pigmentation, vascularity); the presence of edema, swelling, and bulging; surface characteristics such as moistness, dryness, or oiliness; and other unusual findings. The terminology used to describe mucocutaneous lesions is not only descriptive but may at times be suggestive of the underlying cause. The pattern of distribution of the various lesions is also important and may be described as linear, annular (in a ring), or serpiginous (in a curvilinear pattern, serpent-like).

Figure 3.1. Normal skin.

Figure 3.2. Normal mucosa.

Primary Lesions of the Skin and Oral Mucosa

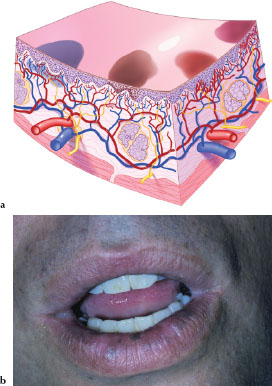

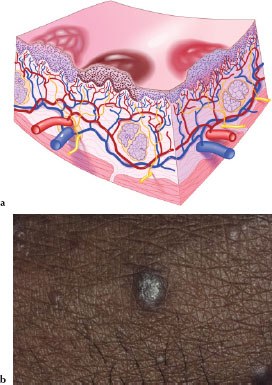

Macule

A macule (Figures 3.3a and 3.3b) is a circumscribed, flat lesion less than 1 cm in size, varied in shape and color, and may represent hyperpigmented, hypopigmented, or vascular abnormalities. Figure 3.3b is an example of multiple macules on the lower lip due to physiologic pigmentation.

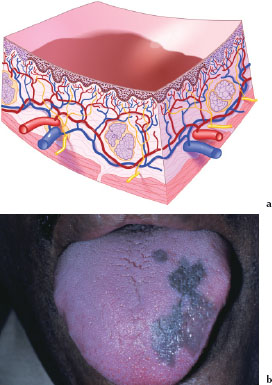

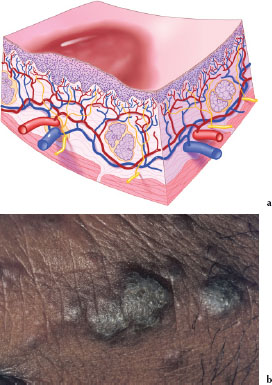

Patch

A patch (Figures 3.4a and 3.4b) is a circumscribed, flat lesion larger than 1 cm in size, varied in shape and color, and may represent hyperpigmented, hypopigmented, or vascular abnormalities. Figure 3.4b is an example of a patch on the dorsum of the tongue due to physiologic pigmentation.

Figures 3.3.a and b. Macule.

Figures 3.4.a and b. Patch.

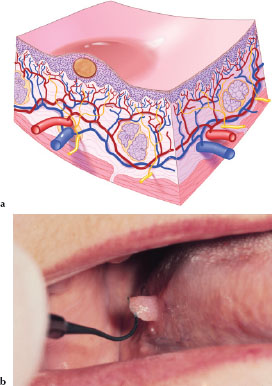

Papule

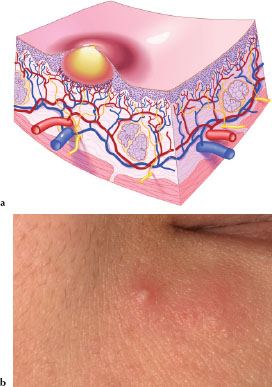

A papule (Figures 3.5a and 3.5b) is a circumscribed, elevated, superficial, solid lesion less than 1 cm in size, varied in shape and color, and may reflect hyperplasia of cellular structures or represent cellular infiltrates. Figure 3.5b is an example of a dermal papule in a patient with lichen planus.

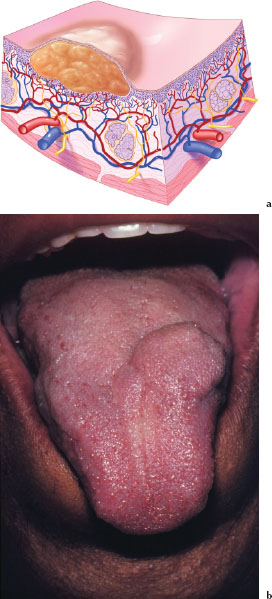

Plaque

A plaque (Figures 3.6a and 3.6b) is a circumscribed, elevated, superficial, solid lesion larger than 1 cm in size, varied in shape and color, and may reflect hyperplasia of cellular structures, represent cellular infiltrates, or may be formed by a confluence of papules. Figure 3.6b is an example of a dermal plaque in a patient with lichen planus.

Figures 3.5.a and b. Papule.

Figures 3.6.a and b. Plaque.

Nodule

A nodule (Figures 3.7a and 3.7b) is a solid palpable lesion less than 1 cm in size. Its depth may be above, level with, or beneath the skin or mucosal surface. Nodules may be the result of inflammatory, neoplastic, or metabolic processes. Descriptors such as soft, firm, hard (bony), fixed, movable, pedunculated (has a stem-like connecting part, a stalk by which a nodule or a tumor is attached to normal tissue), or sessile (attached by a base; not pedunculated or stalked) are helpful when describing these lesions. Figure 3.7b is an example of a pedunculated nodule on the right lateral surface of the tongue.

Tumor

A tumor (Figures 3.8a and 3.8b) is a solid palpable lesion larger than 1 cm in size. Its depth may be above, level with, or beneath the skin or mucosa. Tumors may be the result of inflammatory, metabolic, and neoplastic processes. Descriptors such as soft, firm, hard (bony), fixed, movable, pedunculated, or sessile are helpful when describing these lesions. Figure 3.8b is an example of a tumor affecting the dorsum of the tongue.

Figures 3.7.a and b. Nodule.

Figures 3.8.a and b. Tumor.

Wheal

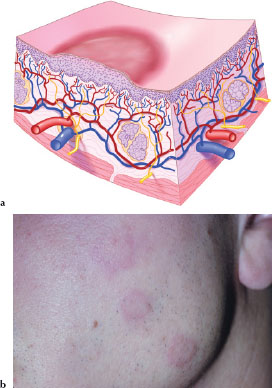

A wheal (Figures 3.9a and 3.9b) is an edematous, rounded or oval transitory papule of variable size, usually the result of an allergic reaction. Figure 3.9b is an example of wheals on the face of a patient with an allergy to latex.

Vesicle

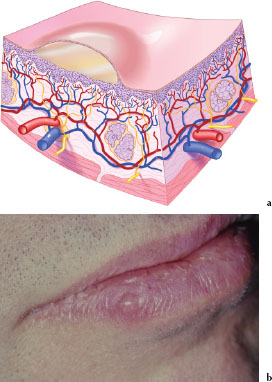

A vesicle (Figures 3.10a and 3.10b) is a circumscribed elevated intraepithelial or subepithelial lesion less than 1 cm in size, which contains a serous fluid. Figure 3.10b is an example of a vesicle associated with recurrent herpes labialis.

Figures 3.9.a and b. Wheal.

Figures 3.10.a and b. Vesicle.

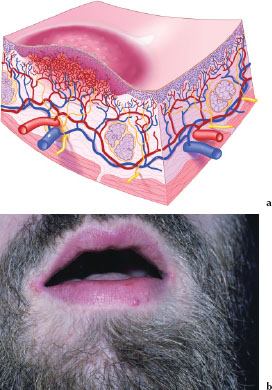

Bulla

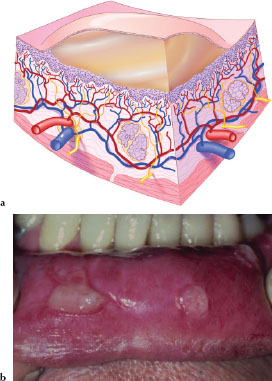

A bulla (Figures 3.11a and 3.11b) is a circumscribed elevated intraepithelial or subepithelial lesion larger than 1 cm in size, which contains a serous fluid. Figure 3.11b is an example of multiple bullae occurring on the inner aspect of the lower lip in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris.

Cyst

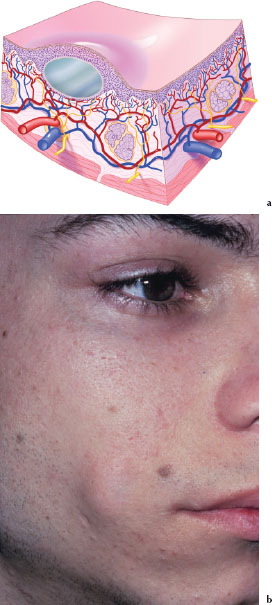

A cyst (Figures 3.12a and 3.12b) is an encapsulated lesion of variable size in subcutaneous or submucosal tissue filled with liquid or semisolid material. Figure 3.12b is an example of a dermoid cyst; the lesion is located about 2 cm lateral to the comissure of the mouth.

Figures 3.11.a and b. Bulla.

Figures 3.12.a and b. Cyst.

Pustule

A pustule (Figures 3.13a and 3.13b) is a circumscribed elevation of variable size and shape containing a purulent exudate. Depending on the color of the purulent exudates, it may appear white, yellow, or greenish-yellow. Figure 3.13b is an example of a dermal pustule.

Hemangioma

A hemangioma (Figures 3.14a and 3.14b) is a red irregular macule or patch of variable size and shape caused by dilation of dermal or mucosal capillaries. Figure 3.14b is an example of capillary hemangioma located on the patient’s lower lip.

Figures 3.13.a and b. Pustule.

Figures 3.14.a and b. Hemangioma.

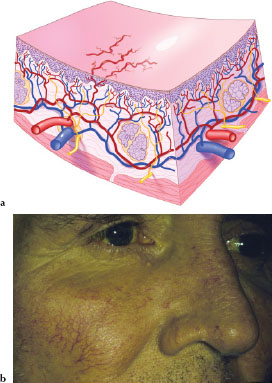

Telangiectasia

Telangiectases (Figures 3.15a and 3.15b) are serpiginous lesions caused by permanent dilation of superficial capillaries. Figure 3.15b is an example of multiple telangiectases on the face of a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver.

Secondary Lesions of the Skin and Oral Mucosa

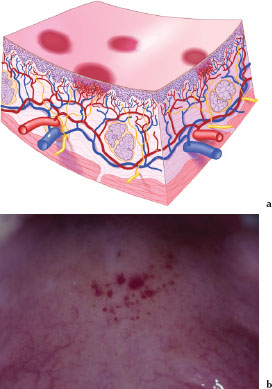

Petechia

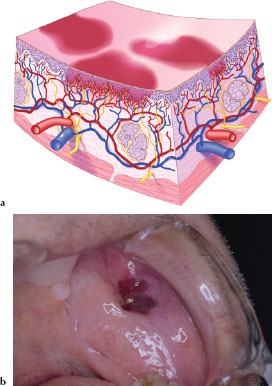

A petechia (Figures 3.16a and 3.16b) is a circumscribed deposit of extravasated blood or blood pigments less than 2 mm in size. Figure 3.16b is an example of multiple petechiae occurring on the soft palate in a patient taking clopidogrel, an antithrombotic agent.

Figures 3.15.a and b. Telangiectasia.

Figures 3.16.a and b. Petechiea.

Purpura

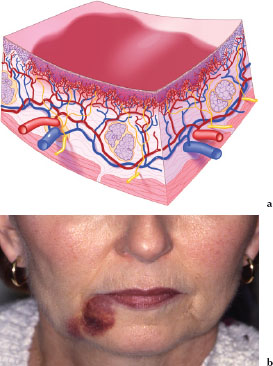

A purpura (Figures 3.17a and 3.17b) is a circumscribed deposit of extravasated blood or blood pigments between 2 and 10 mm in size. Figure 3.17b is an example of a purpura on the left buccal mucosa secondary to trauma in a patient taking warfarin, an oral anticoagulant.

Ecchymosis

An ecchymosis (Figures 3.18a and 3.18b) is a circumscribed deposit of extravasated blood or blood pigments larger than 1 cm in size. Figure 3.18b is an example of a large ecchymotic lesion secondary to trauma associated with a minor salivary gland biopsy.

Figures 3.17.a and b. Purpura.

Figures 3.18.a and b. Ecchymosis.

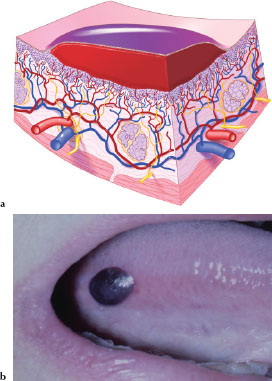

Hematoma

A hematoma (Figures 3.19a and 3.19b) is an accumulated mass of extravasated blood that usually clots to form a solid swelling of variable size and shape within a tissue. Figure 3.19b is an example of a hematoma affecting the lateral border of the tongue in a patient who was taking heparin, a parenteral anticoagulant.

Scale

Scales (Figures 3.20a and 3.20b) are characterized by abnormal shedding (desquamating), usually of dry and flaky, dead epithelial cells. Figure 3.20b is an example of scaly lesions occurring on the forearm of a patient with psoriasis.

Figures 3.19.a and b. Hematoma.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses