Chapter 29 Viral hepatitis

These may be classified into two groups depending on the viral transmission route:

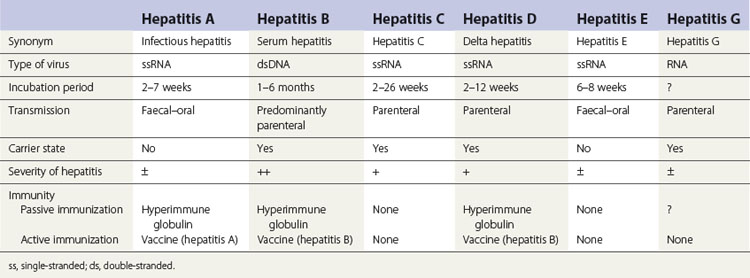

The various types of viral hepatitis differ in severity of infection, morbidity, mortality rate, presence or absence of a carrier state and frequency of long-term sequelae such as cirrhosis and cancer. The main differences between the hepatitides caused by these viruses are shown in Table 29.1.

Hepatitis B

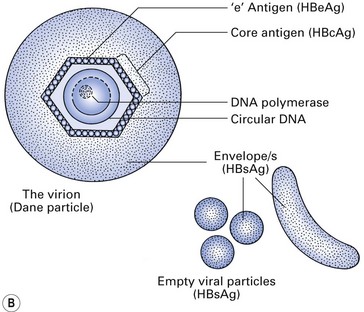

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA hepadnavirus (hepa: liver + DNA), which is structurally and immunologically complex. Electron microscopy of HBV reveals three distinct particles (Fig. 29.1):

Epidemiology

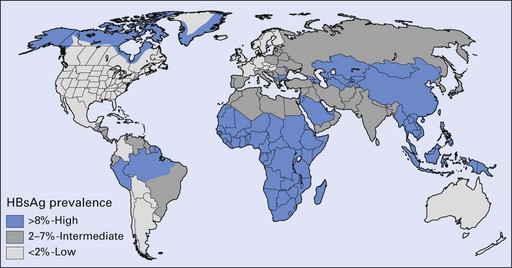

The prevalence of hepatitis B varies greatly in different parts of the world: it is higher in African and Asian countries than in the Americas, Australia and western Europe (Fig. 29.2); in urban than in rural areas; and in men than in women. In developed countries, the risk of exposure to hepatitis B is high in certain categories of people, as shown in Table 29.2. Several variants of HBV are now known, and when these involve rearrangement of the surface antigens, existing vaccines may not be protective. This has come to light as a few individuals who had been successfully immunized against HBV but who were at high risk of infection nevertheless contracted hepatitis B. A variant HBV, HBV-2, has been described in West Africa, the Middle East, Spain, France, Taiwan, New Zealand and the USA, and another has been reported from Italy, Greece and the UK. Both variants are able to infect persons immunized against the usual form of HBV.

Carrier state and identification of carriers

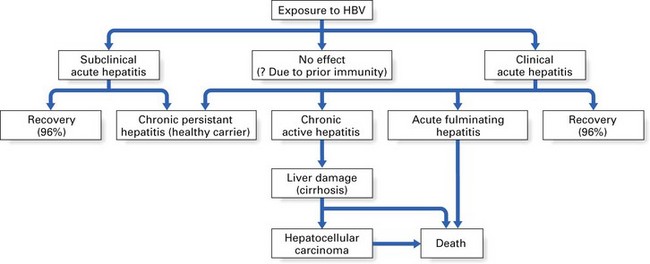

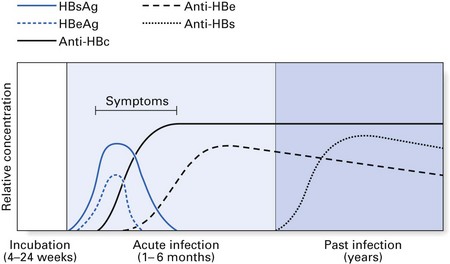

Most patients who contract hepatitis B recover within a few weeks without any sequelae (Fig. 29.3). However, serological markers of previous HBV infection are invariably present in these patients for prolonged periods. Such markers take the form of antibodies to various components of the HBV. A minority (2–5%) fail to clear HBV by 6–9 months and consequently develop a chronic carrier state. This state more frequently follows anicteric HBV infection (i.e. infection without jaundice). The converse of this is that a majority of infections that lead to jaundice resolve without a carrier state; hence, a history of jaundice in a patient in most instances indicates little or no risk in terms of hepatitis B transmission.

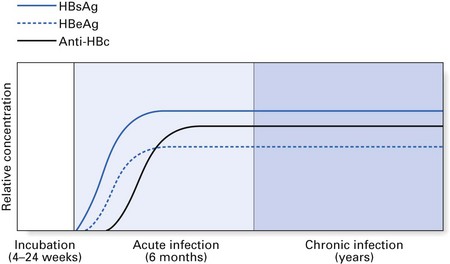

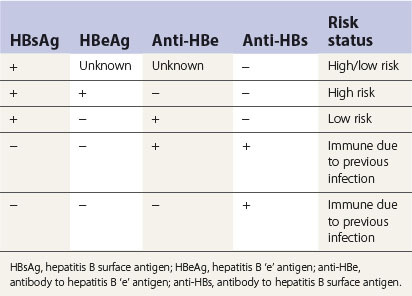

The chronic carriers of hepatitis B infection fall into two main groups: those with chronic persistent hepatitis (the so-called ‘healthy carrier’ state) and those with chronic active hepatitis (Fig. 29.3). In chronic persistent hepatitis, the patient does not develop liver damage and is generally in good health, although the liver cells persistently produce viral antigen (HBsAg) because of the integration of the viral genome into the DNA of the hepatocytes. The second group of chronic carriers are extremely infectious as they harbour the infective Dane particles in their blood. In addition, they are very susceptible to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nonetheless, the chronic active hepatitis group represents a small minority of hepatitis B patients. In general, infection with HBV leads to complete recovery in most individuals, while only about 2–5% develop a carrier state. These two disease states elicit characteristic serological profiles in the affected individual during various phases of the disease, as shown in Figures 29.4 and 29.5.

Diagnosis and serological markers

Diagnosis of HBV is complicated by the variety of serological markers and the complex sequelae of the disease itself. Table 29.3 summarizes the significance of the serological markers described below:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses