CHAPTER 29 Practice Management

PERSONNEL SYSTEMS

PRACTICE ADMINISTRATOR

The business of managing and administering a dental practice has become complex and time consuming for the dentist, even with a well-trained staff. Some larger dental practices now hire well-educated, trained practice administrators. “The key responsibilities of a Practice Administrator could be compared to those of a Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of any corporation1:

INTERVIEWING AND HIRING

The following steps should make the interview more effective:

Two of the most desirable traits in a dental team member are (1) a warm, empathetic personality and (2) cognitive ability, defined as aptitude for learning and capacity to draw from past experience in new situations. Several excellent instruments are on the market to measure cognitive ability and various aspects of personality and behavioral style (e.g., Cognitive Ability Testing Instrument — Wonderlic Personnel Test, Wonderlic, Inc., Libertyville, IL, www.wonderlic.com; Personality and Behavioral Style Instrument — DiSC Classic [Personal Profile System], Inscape Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, www.inscape.com.)

An offer may be made after the working interview. If the applicant will not be hired following the first or second interview, he or she may be told at that time or notified by mail within 1 week of either interview. If an applicant is rejected, maintain all applications, test forms, and other paperwork for at least 1 year in case a complaint concerning unfair hiring practices is filed by the rejected applicant.

ORIENTATION AND TRAINING

In The One Minute Manager, a book long-favored by business managers, Blanchard and Johnson wrote, “Most companies spend 50% to 70% of their money on people’s salaries. And yet spend less than 1% of their budget to train their people. Most companies, in fact, spend more time and money on maintaining their buildings and equipment than they do on maintaining and developing people.”2

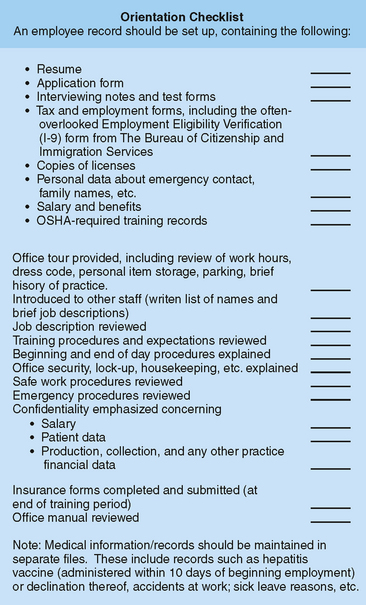

The most effective way to orient new employees is to follow a checklist, which ensures that each new staff member will receive similar information. Fig. 29-1 is an example of an orientation checklist for new employees.

In the most successful practices, the dentist and team members realize that training is an ongoing process; dental professionals continue to learn about new methods and materials in order to better care for patients and maintain professional licenses. Attendance at CE courses, review of current literature and journals, and group study using audiotapes, DVDs, CDs, and so on are appropriate for continuous training. A portion of each staff meeting can be used for additional training and discussions of new treatment methods and materials. Also, the establishment of an office library makes books, journals, and audiovisual aids easily available to all team members. Learning together strengthens a dental team and encourages pride in personal and professional growth.

WAGE AND BENEFIT ADMINISTRATION

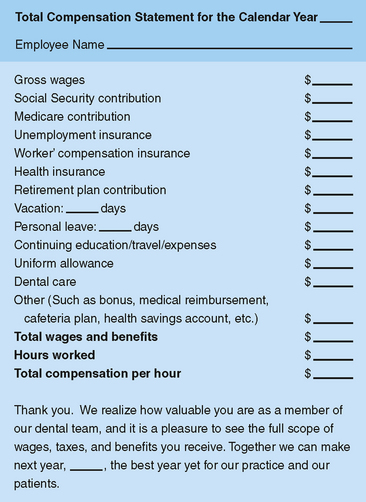

Employees receive more than wages; net pay is only one part of a complete compensation package. Although higher take-home pay with fewer benefits may attract some employees, fair wages with expanded benefits generally help retain team members. Each employee should be given an annual total compensation statement listing gross wages, employer-paid taxes, and the dollar value of benefits such as vacation, personal leave, insurance, uniform allowance, and free or reduced-cost dental care. Fig. 29-2 is an example of an individual total compensation statement. Receiving an actual statement of wages and benefits lets employees perceive their full value. The dentist should communicate to staff members how valuable they are to the practice rather than how much they cost the practice. Although it is a subtle difference, such phrasing can boost staff members’ professional pride, dedication, and loyalty to the practice. Auxiliary personnel who are made to feel valued and appreciated are generally more productive than those told what they “cost” the practice.

Salaries should be evaluated at least yearly; raises are based on merit (positive behavior and work deserving praise), increases in cost of living (inflation), and the overall economic status of the practice.

PERSONNEL RECORDS

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses