CHAPTER 29 COMPLICATIONS AND FAILURES

TREATMENT AND/OR PREVENTION

To understand complications and failures it is necessary to delve into the literature to examine the etiology that generated the problems with the implant. To clarify and understand these concerns better, the author reviewed the literature to ascertain what the etiological factors were. In 1993 Babbush and Shimura reported on the 5-year statistical and clinical observations with IMZ (Attachment International Inc., Burlingame, CA) two-stage osseointegrated implants.1 Of the 1059 implants reviewed over a period of 5 years, the total number of failures was 24 in the maxilla and 4 in the mandible for a total of 28.1 Babbush et al. reported on the titanium plasma-sprayed Swiss screw implant system in the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in 1986.2 The 1991 textbook Implants: Principles and Practices also reported on a large number of cases.3 Wheeler reported an 8-year clinical retrospective study of titanium plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite-coated implants in 1996.4 Buchs et al. reported on his interim clinical study on threaded hydroxyapatite-coated implants with 5-year postrestoration safety and efficacy.5 Jaffin and Berman reported the excessive loss of Brånemark fixtures in type 4 bone with a 5-year analysis.6 Huerzeler published “Reconstruction of the Severely Resorbed Maxilla with Dental Implants and Augmented Maxillary Sinus: A Five-Year Clinical Investigation” in 1991.7 This was then followed by two papers by Arun Garg, “Complications Associated with Implant Surgical Procedures, Part I: Prevention” and “Complications Associated with Implant Surgical Procedures, Part II: Treatment” in May 2004 (published in Dental Implantology Update).8,9 A series of papers followed, which are documented in the references.10–29

Categorization of Etiological Factors in Complications and Failures of Implants

Categorization of Etiological Factors in Complications and Failures of Implants

After reviewing the literature it was evident to the author that an appropriate categorization of the etiological factors of complications and/or failure could include three main categories: (1) the implant system, (2) the patient, and (3) the doctor (Box 29-1).

Implant System

Implant system review based on failure potential should evaluate such aspects as poor overall design of the body of the implant; insufficient implant size leading to poor bioengineering and support; presence of a large microgap between the various components, abutments, or internal connections; chronic screw loosening; abutment and/or implant precision; and acceptability of implant surface for osseointegration (Box 29-2).30,31

Patient

Factors in patient-based failures include parafunctional habits, smoking, preexisting diseases (for example, diabetes and/or connective tissue diseases), and physical impairments/disabilities that inhibit maintenance and good oral hygiene on a daily basis, which put the implant at risk. Other factors that contribute to patient failure include the development of postoperative disease states (such as diabetes or connective tissue pathology) and neglect of oral hygiene and home care on a daily basis. Recall on a routine basis provides the practitioner an opportunity to locate and diagnose inappropriate care and/or other problems that could be reversed (Box 29-3).32–50

Doctor

Doctor failures can be divided into four categories: preoperative, intraoperative, postsurgical, and restorative (Box 29-4).51–75

Preoperative

Preoperative failure factors include recognition of poor quality and quantity of soft tissue; poor quality and quantity of hard tissue; inadequate preliminary procedures such as appropriate orthodontics, periodontics, endodontics; poor occlusal relationships without proper recognition; and inappropriate treatment plan development (Box 29-5).

Interoperative

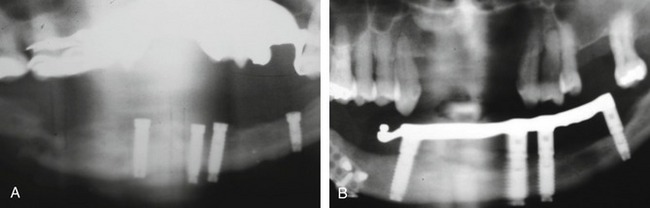

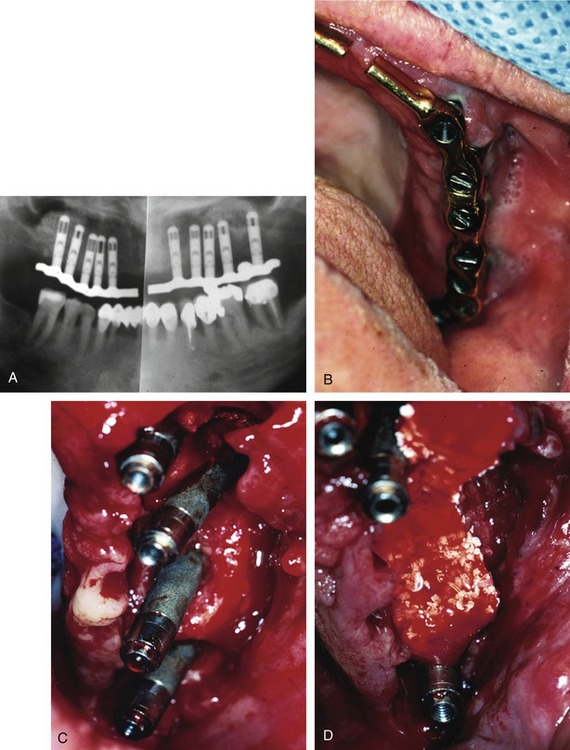

Problems that may be initiated by the doctor during the surgical procedure range from an oversized osteotomy with a “spinner” of the implant or an undersized osteotomy, which would generate excessive pressures in trying to seat the implant. Excessive drill speed and pressure would cause a precipitous rise in the frictional heat, elevating the temperature above 42°-44° C and actually cooking the cytoplasm of the cells. Over time, this would create a necrosis of the surrounding hard tissues. Insufficient irrigation would cause the same potential problem. A sinus perforation that was not recognized or cared for postsurgically could lead to infection and/or lack of osteointegration. Inappropriate bioengineering could lead to inappropriate length, diameter, or number of implants to support the restoration. Additionally, encroachment of the mental foramen, or perforation of the mandibular canal could lead to a variety of neurological problems. Malposition of the implant could result in the inability to restore the implant(s) or a compromised restoration, leading to poor hygiene, breakdown of the hard and soft tissues, and ultimate loss of the system, as well as compromised aesthetics. Mandibular fracture secondary to excessive pressures and forces (Figure 29-1), especially in the severely atrophied mandible, is quite possible (Box 29-6).

Postsurgical

Postsurgical hemorrhage due to poor wound care, suturing technique, patient medication, or undiagnosed bleeding disorders is always a potential hazard. Presurgical medical complications that were not cared for in the postoperative course can lead to inadequate or poor wound closure. Proper postsurgical wound care, pain management, infection control, and oral hygiene and maintenance are vital (Box 26-7).

Restorative

Some of the characteristics of restorations that may contribute to failure are a provisional prosthesis with poor design, a poor finish line, residual cement, and malocclusion due to excessive length of cantilevers. The final prosthesis may have poor contours, inappropriate materials, or inadequate or traumatic occlusion. Fixed versus removable prostheses, splinting versus nonsplinting to adjacent teeth, excessive cantilever lengths, and cementation versus screw retention may all be related to complications or failure (Box 29-8).

Treatment Protocol

Treatment Protocol

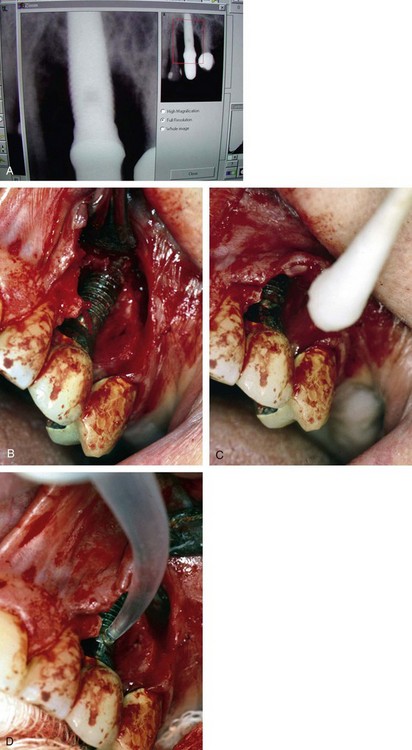

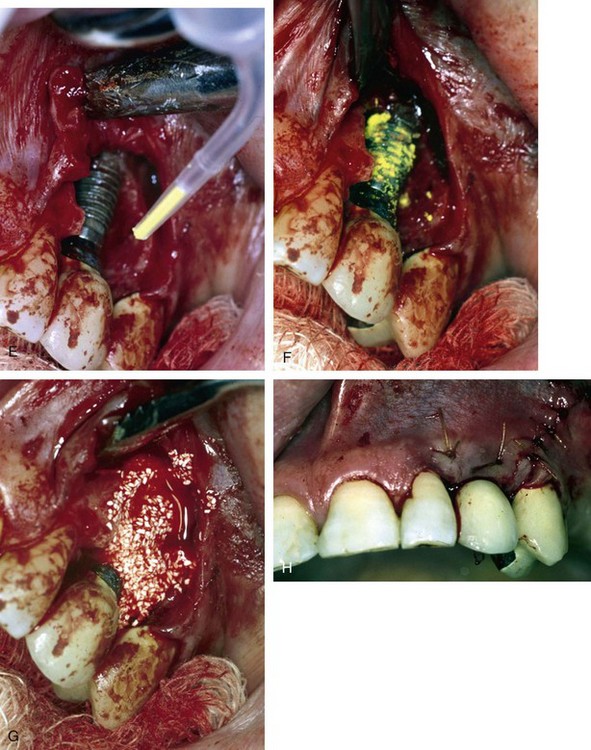

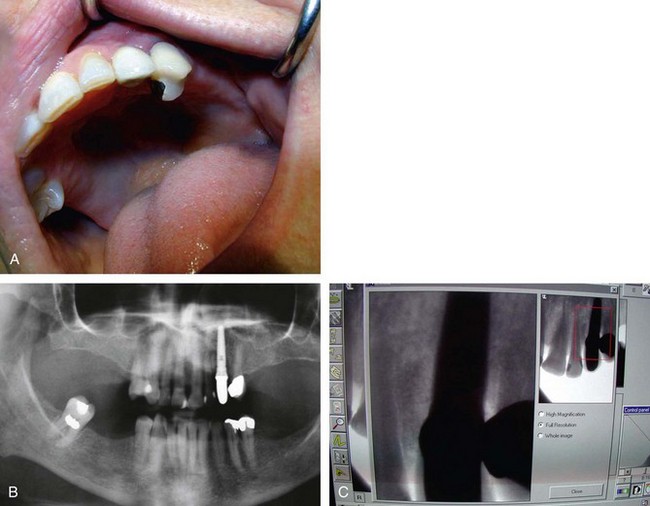

Once all of the soft tissues have all been removed from the surface of the implant and the osseous structures have been recontoured, a solution of 1% citric acid is used topically on the surface of the implant and surrounding tissues to detoxify the surface. The area is irrigated with saline after 1.5-2 minutes. Monocycline (Arestin, OraPharma, Inc., Warminster, PA) 1 mg. is injected over the entire surface of the implant and surrounding hard tissue. Once again, the area is irrigated to wash away the monocycline after 1-2 minutes. A composite graft composed of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) fabricated with the usual protocol is then combined with a granular high-porosity bone substitute (Algisorb, Osseous Technologies of America, Newport Beach, CA). The mucoperiosteal tissues are then repositioned and sutured with interrupted 4-0 chromic sutures. The patient is followed for approximately 3 months, during which reconsolidation of the surrounding bone is carried out (Box 29-9) (Figures 29-2 through 29-9).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses