CHAPTER 28 Multidisciplinary Team Approach to Cleft Lip and Palate Management

Cleft lip and palate, the most common of the craniofacial anomalies, are severe congenital anomalies that have an incidence of 0.28 to 3.74 per 1000 live births globally. In the United States, cleft lip and palate occur in approximately 1 in 1000 newborns. The incidence varies widely among races. Cleft lip and palate occur in about 1 in 800 white newborns, 1 in 2000 black newborns, and 1 in 500 Japanese or Navaho Indian newborns. Isolated cleft palate occurs in about 1 in 2000 newborns and demonstrates less racial variation. Cleft lip and palate together account for approximately 50% of all cases, whereas isolated cleft lip and isolated cleft palate each occur in about 25% of cases. Many of these congenital anomalies appear to be genetically determined, although the majority are of unknown cause or are attributable to teratogenic influences (see Chapter 6).

CLASSIFICATION OF CLEFT LIP AND PALATE

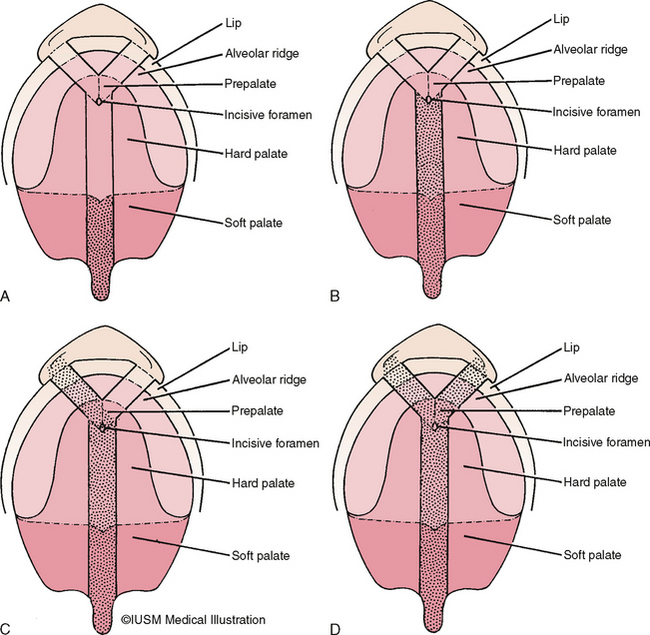

There is a tendency to conceptualize cleft lip and palate as a homogenous anomaly. If that was true, a treatment plan applicable to all cases could be formulated. However, the reality is that clefts vary widely in their clinical presentations (Fig. 28-1).

To standardize reporting of cleft lip and palate, the Nomenclature Committee of the American Association of Cleft Palate Rehabilitation devised a classification system that later was adopted by the Cleft Palate Association. The complexity of this system, however, has made its acceptance less than overwhelming. Veau proposed the most frequently used system.1 He classified clefts of the lip as follows:

Veau divided palatal clefts into four classes as follows (Fig. 28-2):

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CLEFT LIP AND PALATE TEAM

Children born with cleft lips and palates have many problems that need to be solved for successful habilitation. The complexity of these problems requires that numerous health care practitioners cooperate in providing the specialized knowledge and skills necessary to ensure comprehensive care. The cleft palate team concept has evolved from that need.

To address the many treatment regimens and different care protocols, the American Cleft Palate– Craniofacial Association (http://www.cleftpalate-craniofacial.org) convened a consensus conference on recommended practices for the care of patients with craniofacial anomalies. This conference produced the document “Parameters for Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Cleft Lip/Palate or other Craniofacial Anomalies.”2 This serves as a guide for implementing the multidisciplinary approach to cleft and craniofacial care and is used by teams in the United States and Canada.

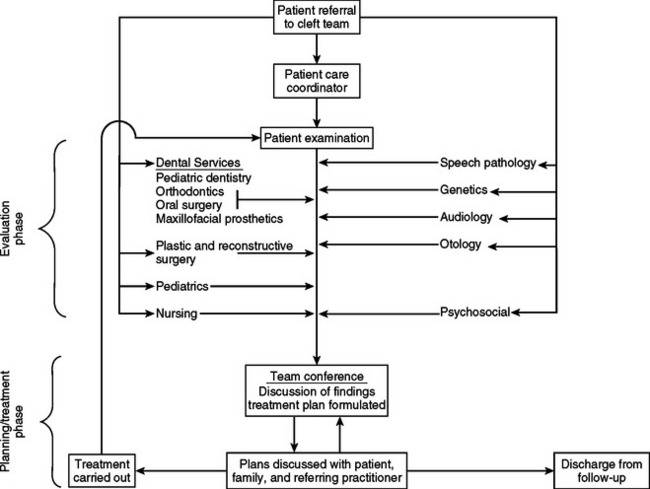

These care providers assess the patient’s medical status and general development, dental development, facial esthetics, psychological well-being, hearing, and speech development (Fig. 28-3). Team members must communicate effectively among themselves, with the child and parents, and with the primary care physician and dentist. Individuals on the team must respect one another’s opinions and be flexible in planning and carrying out therapy. Periodic evaluation is necessary to assess the effect of previous therapy and to determine whether an alternative approach may be necessary. A team conference immediately after patient examination is a desirable way to discuss current problems and plan timely therapy.

Whitehouse describes the clinical team as a “close, cooperative, democratic, multiprofessional union devoted to a common purpose—the best treatment of the fundamental needs of the patient.”3

GENERAL RESPONSIBILITIES OF TEAM MEMBERS

DENTAL SPECIALTIES

The pediatric dentist should discuss with the patient and parents the traditional dental problems associated with clefting. Any one, or several, of the following conditions may occur with a significantly greater frequency than in the general population:

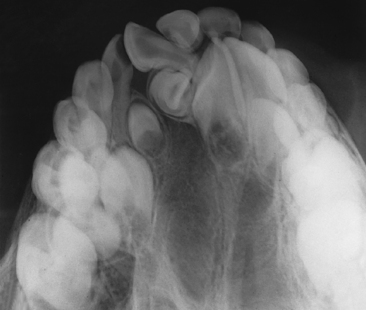

The orthodontist plays a key role in the diagnosis and treatment of a cleft condition by obtaining records necessary for diagnosis and treatment planning. These include cephalometric and panoramic radiographs, study models, and diagnostic photographs. Analysis of these records enables the orthodontist to describe and quantitate the facial skeleton and soft tissue deformities. Using expertise in the growth and development of the facial skeleton, this specialist can identify problem areas and, with some limitations, predict growth and development. Many team members depend on the orthodontist’s analysis and quantitations of the cleft anomaly for treatment planning.

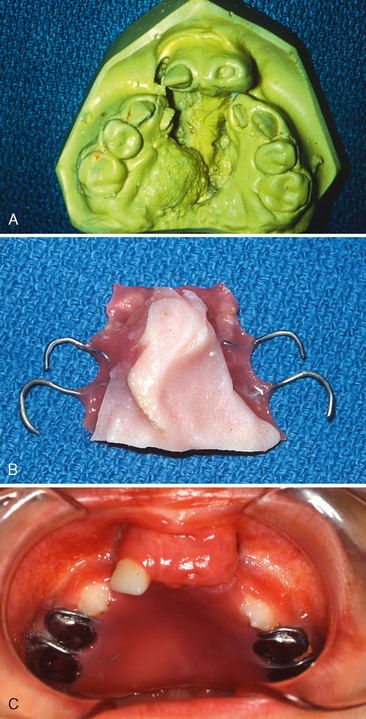

Many patients with clefts have congenitally missing teeth or malformed teeth that may need to be removed. In these cases, masticatory function, speech, and orofacial esthetics are compromised, and successful habilitation dictates that these missing teeth be replaced to achieve as near normal a condition as possible (Fig. 28-8). The maxillofacial prosthodontist may do this with fixed or removable appliances or with a combination of the two.

Occasionally, patients demonstrate aberrant speech patterns caused by failure of the soft palate to elevate properly. In such cases, a palatal lift appliance is fabricated to aid the speech mechanism. In other cases the maxillofacial prosthodontist may fabricate a speech bulb prosthesis to aid or augment the velopharyngeal mechanism. In patients with considerable escape of air through persistent palatal fistulas, the fistulas can be obturated (Fig. 28-9).

MEDICAL AND ALLIED HEALTH SPECIALTIES

The medical geneticist examines the patient to find characteristics of syndromes associated with cleft lip and palate. Consideration is given to the genetic basis for the anomaly, and this information is related to the parents. Genetic counseling is a very important function of the geneticist. Parents are vitally interested in risk assessment relative to future offspring, and other family members who may be at risk are often counseled (see Chapter 6).

An additional responsibility may be to conduct a nasopharyngoscopic examination of the speech mechanism. If a defect is identified, the plastic surgeon may perform a pharyngoplasty to improve velopharyngeal function. The final role is to correct internal or external cleft nasal deformities.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY SEQUENCING OF TREATMENT IN CLEFTS

STAGE I (MAXILLARY ORTHOPEDIC STAGE: BIRTH TO 18 MONTHS)

McNeil in the 1950s4,5 and other authors since then have advocated various prosthetic appliances, both active and passive, for the treatment of infants born with unilateral and bilateral clefts of the lip and palate. One such prosthesis, an intraoral maxillary obturator, has proved beneficial by providing an artificial palate. The advantages of this prosthetic therapy include the following:

In a study by Jones, maxillary obturators were constructed to facilitate feeding for 51 infants with unilateral or bilateral cleft lip and palate.6 From birth, each infant had continuously experienced feeding difficulties before obturator therapy. After the infants had worn the obturator for at least 8 months, parents reported that they were more comfortable while feeding their infants and that nasal discharge was reduced. The time required for feeding and the difficulty experienced by the parents were also reduced. Of particular importance was the reported reduction of parental apprehension during feeding. All parents recommended the obturator for others who have infants with cleft lips and palates. It was also reported that the weights of the infants at 1, 3, and 6 months of age consistently remained at, or above, the 50th percentile compared to normative growth data. No fluctuation in weight was noted even after primary lip closure at about 3 months of age.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses