Dietary factors and health and disease

Diet and Health

Dietary factors have been implicated as influencing a range of conditions (Box 27.1; see also Ch. 36).

Minimizing intake of saturated fat (especially from dairy sources) and partially hydrogenated vegetable fats lowers the risk of coronary artery disease and some cancers (Chs 5 and 22). In contrast, consumption of monounsaturated fats, such as olive oil, and omega oils may be beneficial. Generous amounts of vegetables and fruit daily appear to offer some protection against cancers of the stomach, colon and lung, and possibly against cancers of the mouth, larynx, cervix, bladder and breast (Ch. 22). Citrus fruits and juices in excess, however, may cause tooth erosion.

Carbohydrates as wholegrain, unrefined products may offer some protection against colon cancer, diverticulitis and dental caries. A high-fibre diet may offer some protection against hypertension and coronary heart disease (Ch. 5).

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is mainly a consequence of lack of resources and education, and results from imbalance between people’s needs and their intake of nutrients, which can lead to obesity or to syndromes of deficiency, dependency or toxicity. Overnutrition develops over time from overeating; insufficient exercise; overprescription of therapeutic diets, including parenteral nutrition; excess intake of vitamins, particularly pyridoxine (vitamin B6), niacin and vitamins A and D; and excess intake of trace minerals. Undernutrition (starvation) usually results from inadequate intake; malabsorption; abnormal systemic loss due to diarrhoea, haemorrhage, renal failure, cancer or excessive sweating; infection; or addiction to drugs. Undernutrition can develop rapidly.

Obesity

General aspects

To most people, the term ‘obesity’ means the state of being very overweight; however, ‘overweight’ is sometimes defined as an excess amount of body weight that includes muscle, bone, fat and water, while ‘obesity’ specifically refers to excessive body fat. Some people, such as bodybuilders or other athletes with a lot of muscle, can be overweight without being obese. Obesity is the main nutritional problem in developed countries (Fig. 27.1), though some body fat is needed for energy, heat insulation, shock absorption and other functions. As a rule, women have more body fat than men. Men with more than 25% body fat and women with more than 30% body fat are obese.

Almost 25% of North American adults are now clinically obese and obesity is increasing in children. More than 60% of Americans aged 20 years and older are overweight. Europe and Japan follow similar patterns. In 2012 in England, 16% of children and 26% of adults were obese. The prevalence of obesity in England has more than tripled in the last 25 years.

Obesity results from eating more than the body needs – an imbalance between calories in and calories out. Control of eating and weight regulation is complex and involves a range of endocrine and nervous signals, especially peptide YY, ghrelin, insulin, cholecystokinin and leptin (Table 27.1). The body monitors blood glucose concentration, which contributes to the overall regulation of food intake, via GLUT2 transporters, which mediate glucose entry to the cells, and the gluco-kinase enzyme. This makes their intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) supply exquisitely sensitive to glucose availability, and forms the basis for their signalling systems by pancreatic beta-cells; portal vein glucose sensor; carotid bodies; the nucleus of the solitary tract; and the hypothalamus – which triggers a massive sympathetic response to hypoglycaemia, with pounding heart, trembling, anxiety, sweating and hunger. However, the effects of hyperglycaemia on feeding and satiation are less obvious, and may even lead to paradoxical overeating. Leptin (from the Greek leptos, meaning thin) is a protein hormone released by fat cells that counteracts the effects of neuropeptide Y, a potent feeding stimulant secreted by cells in the gut; it has important effects in regulating metabolism, reproductive function and body weight, acting on the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus to suppress eating behaviour and also to increase energy expenditure. Leptin also acts directly on the liver and skeletal muscle, where it stimulates the oxidation of fatty acids in the mitochondria, reducing the storage of fat in those tissues (but not in adipose tissue). The absence of functional leptin (or its receptor) leads to uncontrolled food intake and resulting obesity. Rarely, mutations in the leptin gene or its receptor are found in obese people but these are only a very uncommon cause of morbid obesity. Recombinant human leptin trials in the hope of reducing obesity in humans have so far had no great benefit.

Table 27.1

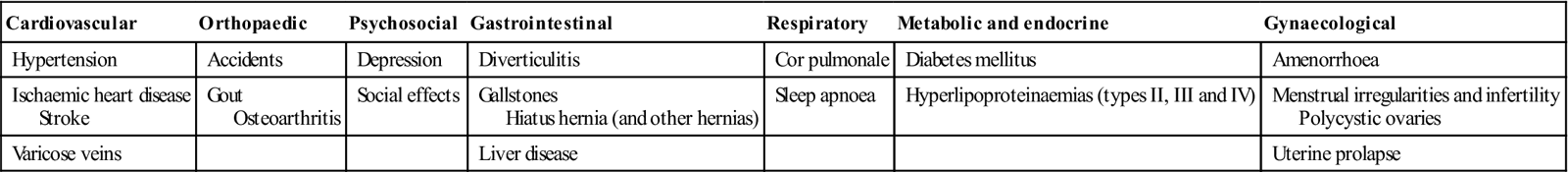

Complications of obesity (plus various cancers)

< ?comst?>

| Cardiovascular | Orthopaedic | Psychosocial | Gastrointestinal | Respiratory | Metabolic and endocrine | Gynaecological |

| Hypertension | Accidents | Depression | Diverticulitis | Cor pulmonale | Diabetes mellitus | Amenorrhoea |

| Ischaemic heart disease Stroke |

Gout Osteoarthritis |

Social effects | Gallstones Hiatus hernia (and other hernias) |

Sleep apnoea | Hyperlipoproteinaemias (types II, III and IV) | Menstrual irregularities and infertility Polycystic ovaries |

| Varicose veins | Liver disease | Uterine prolapse |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Many other factors that appear to affect appetite, satiation and obesity include proinflammatory cytokines (tumour necrosis factor alpha [TNFα], interleukin-6 [IL-6] and IL-1); incretins (cholecystokinin, gastric inhibitory peptide [GIP], glucagon-like peptide 1 and glucagon-like peptide 2); the melanocortin receptor system (MCR); cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART); thyrotropin-releasing hormone; corticosteroids; and growth hormone (for more information, see http://www.bmb.leeds.ac.uk/teaching/icu3/lecture/26; accessed 30 September 2013).

Environmental factors affecting body weight include lifestyle behaviours, such as what a person eats and their level of physical activity. Psychological factors may play a role; many people eat in response to negative emotions such as boredom, sadness or anger. Some anti-depressants can cause weight gain. Genetic factors, hormonal influences, hypothalamic disease (Frohlich, Laurence–Moon–Biedl or Prader–Willi syndromes), endocrinopathies (hypothyroidism, Cushing disease or insulinoma) or drugs (e.g. steroids) can rarely be implicated.

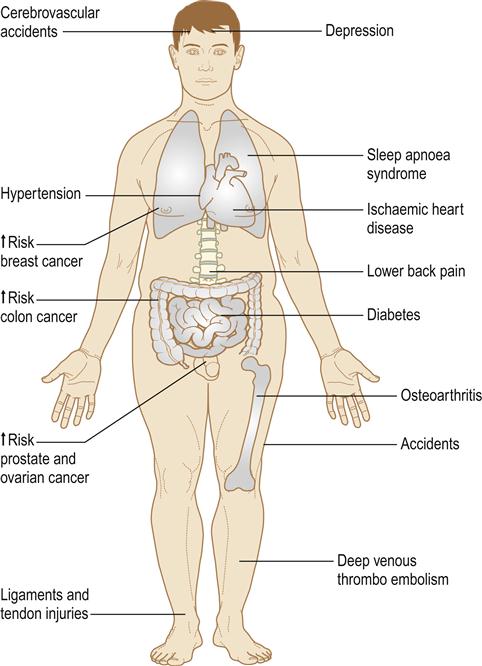

Clinical features

There is about a threefold increase in premature deaths in obese patients because of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke and cancer (see Table 27.1; Fig. 27.2). Obese men are more likely than non-obese men to die from cancer of the colon, rectum or prostate. Obese women are more likely to die from cancer of the gallbladder, breast, uterus, cervix or ovaries.

General management

Measuring body fat is not easy. A simple method is to measure the subcutaneous fat thickness in several parts of the body with skin callipers. The most accurate methods are to weigh the person under water or to use dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Body mass index (BMI), the standard for measuring overweight and obesity, uses a formula based on height and weight: BMI equals weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared (BMI=kg/m2; Table 27.2). Because measuring body fat is difficult, health-care providers often rely on weight-for-height tables – a range of acceptable weights for a person of a given height. However, these tables do not distinguish between muscle and excess fat.

Table 27.2

| BMI (kg/m2) | Classification |

| <18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

| 25.0–29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0–34.9 | Obesity class I |

| 35.0–39.9 | Obesity class II |

| ≥40 | Obesity class III |

Bariatric medicine (from the Greek baros [weight] and –iatrics [medical treatment]) is the term used for the specialty of caring for obese patients. Weight loss is recommended, particularly if there are two or more of the following:

■ Family history of heart disease or diabetes

■ Pre-existing disorders, such as hypertension, hyperglycaemia or hypercholesterolaemia

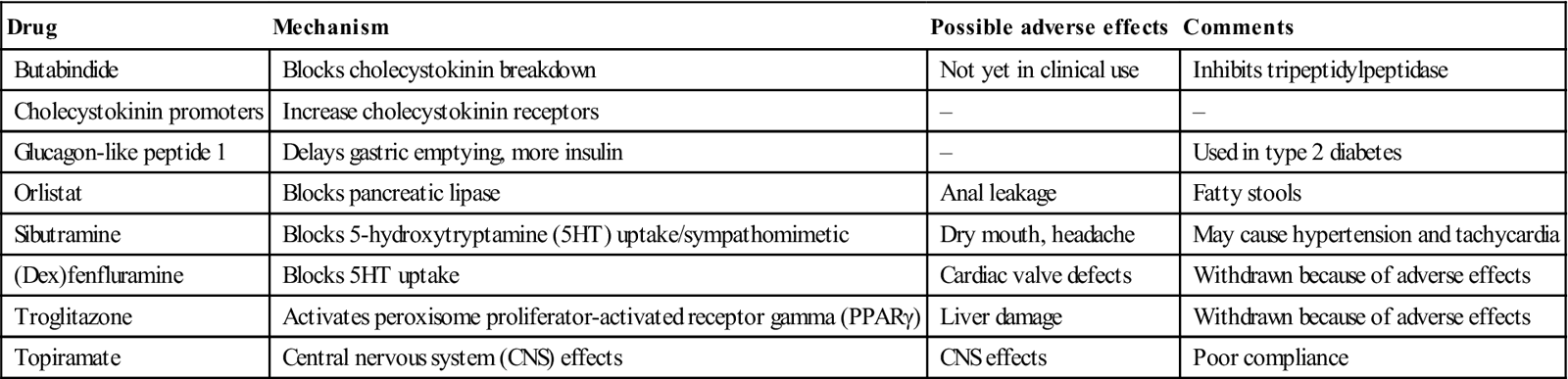

The method of treatment depends on the degree of obesity, overall health condition and motivation to lose weight. It may include a combination of diet, exercise, behaviour modification and sometimes weight-loss drugs (Table 27.3) or surgery. People who have a BMI of 30 or more can improve their health by weight loss – especially if they are severely obese. A weight loss of 5–10% can do much to improve health by lowering blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and preventing type 2 diabetes in people at high risk for it. Sympathomimetic appetite suppressants are used only in the short-term treatment of obesity since their effect tends to decrease after a few weeks. Tesofensine is a new agent of possible benefit.

Table 27.3

Drugs used in treatment of obesity

< ?comst?>

| Drug | Mechanism | Possible adverse effects | Comments |

| Butabindide | Blocks cholecystokinin breakdown | Not yet in clinical use | Inhibits tripeptidylpeptidase |

| Cholecystokinin promoters | Increase cholecystokinin receptors | – | – |

| Glucagon-like peptide 1 | Delays gastric emptying, more insulin | – | Used in type 2 diabetes |

| Orlistat | Blocks pancreatic lipase | Anal leakage | Fatty stools |

| Sibutramine | Blocks 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) uptake/sympathomimetic | Dry mouth, headache | May cause hypertension and tachycardia |

| (Dex)fenfluramine | Blocks 5HT uptake | Cardiac valve defects | Withdrawn because of adverse effects |

| Troglitazone | Activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) | Liver damage | Withdrawn because of adverse effects |

| Topiramate | Central nervous system (CNS) effects | CNS effects | Poor compliance |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

In severe obesity, bariatric surgery may rarely be recommended. It aims at:

vertical banded gastroplasty (Mason procedure, stomach stapling)

laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB; REALIZE® band – lap band)

biliopancreatic diversion (Scopinaro procedure – rare)

Severely obese people can encounter many problems relating to health-care access.

Dental aspects

Bariatric surgeries may be associated with an increased risk for gastro-oesophageal reflux and taking a more cariogenic diet, which in turn might account for the higher amount of carious and erosive tooth surface loss seen in bariatric patients. Jaw wiring of obese patients appears to be an effective and safe way of substantially reducing weight in those in whom simpler methods fail, but relapse frequently follows.

Dental treatment of obese patients may be complicated mainly by the sheer size of the patient and difficulties in accessing the dental chair. Bariatric dental chairs suitable for all patient groups up to 454 kg (1000 lb; 71 st) are available, in which large, overweight, obese and bariatric patients can be safely treated (e.g. Diaco, Barico). Respiration is impaired if the patient is laid supine. The total work of breathing is greater and, even at rest, obese patients need to ventilate more than normal. Some 10% of the grossly obese have hypoventilation, cor pulmonale and episodic somnolence (Pickwickian syndrome).

Local anaesthesia (LA) is satisfactory but may prove more difficult because of the thickness of the tissues. Conscious sedation (CS) may be given if required. Cardiac arrhythmias may be produced by the interaction of halogenated anaesthetics and large doses of amphetamines or amphetamine-like appetite suppressants (all controlled drugs), which should be discontinued a week before general anaesthesia (GA).

Treatment may also be complicated by diabetes or, rarely, by an organic cause of the obesity. Sympathomimetic appetite suppressants may interact with a range of drugs (Box 27.2).

Appetite suppressants, including sibutramine and phentermine, and herbal supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids/caffeine (ma huang, kola nut) can produce dry mouth.

Eating Habits

Vegetarianism

Vegetarianism includes a range of habits (Table 27.4). Vegans are strict vegetarians, avoiding all foods of animal origin, including meat, poultry, fish, dairy products and eggs. This can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (Ch. 8), though this is surprisingly uncommon – vegans typically use yeast extracts and oriental-style fermented foods to provide B12. Calcium, iron and zinc intakes also tend to be low. Lacto-vegetarians include dairy products in their diet. Lacto-ovo-vegetarianism – whose adherents also eat dairy products and eggs – is the most common form of vegetarianism. Pesco-vegetarians eat fish, dairy products and eggs along with plant foods. Semi-vegetarians eat some poultry and fish, dairy products and eggs. Fruitarians eat only fruit and their diet is thus deficient in protein, salt and many micronutrients; this diet is not recommended.

Table 27.4

| Type of vegetarianism | Dietary habits |

| Fruitarianism | Eat only fruit products |

| Veganism | Abstain from all foods from animals, including dairy products |

| Lacto-vegetarianism | Like vegans, but eat dairy products |

| Lacto-ovo-vegetarianism | Like vegans, but eat dairy products and eggs |

| Pesco-vegetarianism | Like vegans, but eat dairy products, eggs and fish |

| Semi-vegetarianism | Like vegans, but eat dairy products, eggs, fish and poultry |

Vegetarians tend to live longer and develop fewer chronic disabling conditions than their meat-eating peers. However, their lifestyle usually also includes regular exercise and abstention from alcohol and tobacco, which may contribute to their improved health. Vegetarians may have less caries. Disadvantages are few; iron deficiency is the main risk. A fruitarian or prolonged lacto-vegetarian diet may suffer from dental erosion; citrus fruits, vinegar and acidic berries are especially responsible, particularly if ingested just before retiring to sleep.

Fad diets

Many commercial diets claim to enhance well-being or reduce weight but some have resulted in vitamin, mineral and protein deficiency states. Cardiac, renal and metabolic disorders, as well as some deaths, have resulted.

Eating Disorders

Eating is controlled by many factors, including appetite; food availability; family, peer and cultural practices; and attempts at voluntary control. Dieting is a common practice in the developed world and heavily promoted by fashion trends, sales campaigns and in some activities (e.g. fashion models). Food fads, selective eating (extreme fussiness) and food avoidance (without any fear of weight gain) are relatively common and usually fairly inconsequential in medical terms. Eating disorders, however, are of concern and are frequent among models, elite performers of certain sports or physical activities, ballet dancers, gymnasium users and bodybuilders.

Dieting to a body weight lower than is needed for health is common; eating disorders are also common and spotting the borderline between the two can be difficult. Eating disorders usually develop during adolescence or early adulthood, most often in females. They often coexist with other mental health issues, such as depression, substance abuse and anxiety disorders; they can disturb growth, lead to endocrine, cardiac and renal disease, and may be fatal. There are probably 90 000 people in UK receiving treatment.

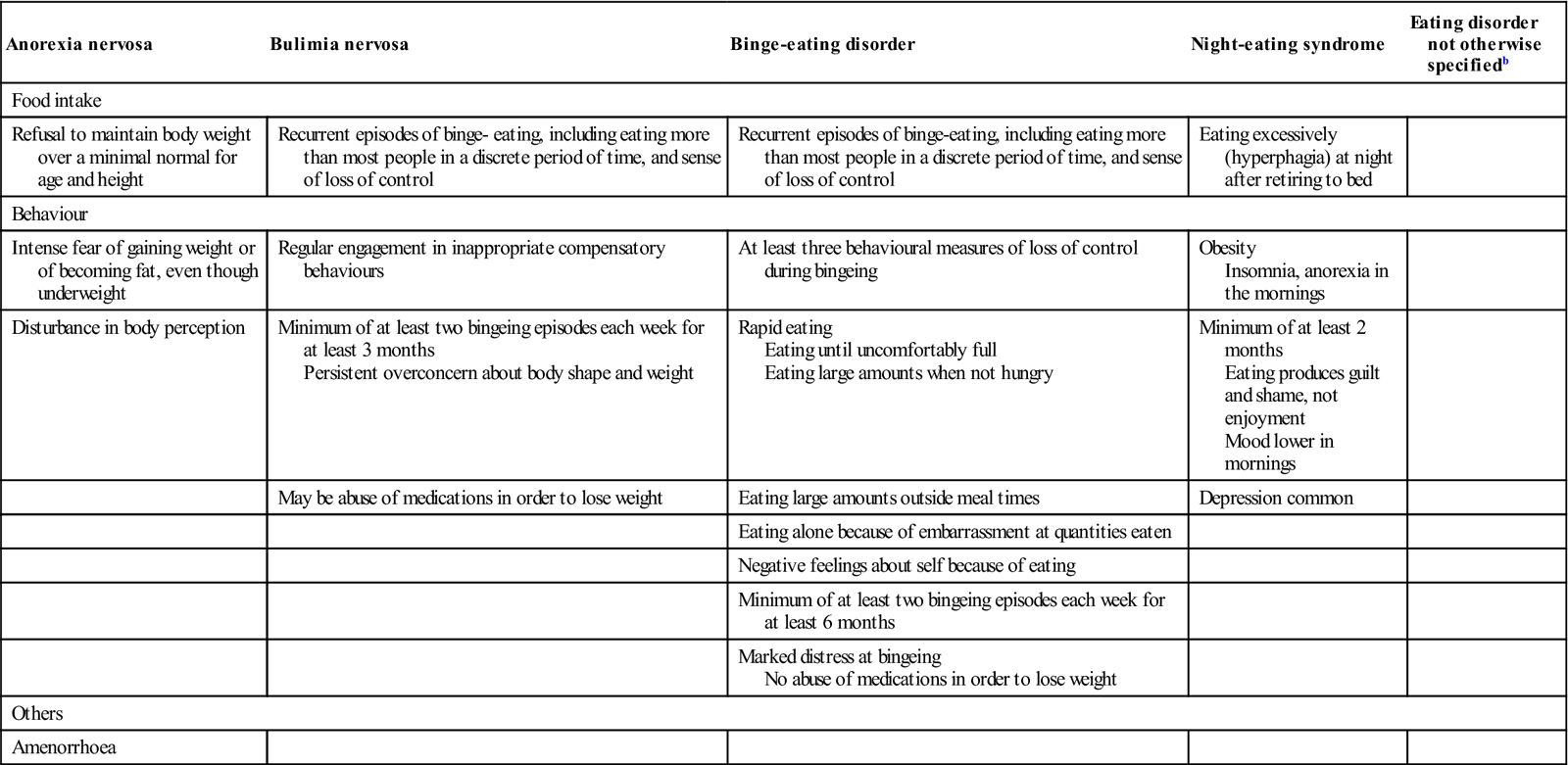

Most people are concerned about their weight, so the early signs of eating disorders may easily be overlooked (Box 27.3). Eating disorders include anorexia nervosa (self-imposed starvation), bulimia nervosa (binge-eating and dieting), binge-eating disorder, and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) (Table 27.5). Night-eating syndrome (NES) is also reportedly common – especially in obese people. Nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder (NS-RED) is not strictly an eating disorder; rather it is a type of sleep disorder in which people eat while ‘sleepwalking’, seeming to be sound asleep.

Table 27.5

< ?comst?>

| Anorexia nervosa | Bulimia nervosa | Binge-eating disorder | Night-eating syndrome | Eating disorder not otherwise specifiedb |

| Food intake | ||||

| Refusal to maintain body weight over a minimal normal for age and height | Recurrent episodes of binge- eating, including eating more than most people in a discrete period of time, and sense of loss of control | Recurrent episodes of binge-eating, including eating more than most people in a discrete period of time, and sense of loss of control | Eating excessively (hyperphagia) at night after retiring to bed | |

| Behaviour | ||||

| Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, even though underweight | Regular engagement in inappropriate compensatory behaviours | At least three behavioural measures of loss of control during bingeing | Obesity Insomnia, anorexia in the mornings |

|

| Disturbance in body perception | Minimum of at least two bingeing episodes each week for at least 3 months Persistent overconcern about body shape and weight |

Rapid eating Eating until uncomfortably full Eating large amounts when not hungry |

Minimum of at least 2 months Eating produces guilt and shame, not enjoyment Mood lower in mornings |

|

| May be abuse of medications in order to lose weight | Eating large amounts outside meal times | Depression common | ||

| Eating alone because of embarrassment at quantities eaten | ||||

| Negative feelings about self because of eating | ||||

| Minimum of at least two bingeing episodes each week for at least 6 months | ||||

| Marked distress at bingeing No abuse of medications in order to lose weight |

||||

| Others | ||||

| Amenorrhoea | ||||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

aModified from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disease version 4 (DSM-IV).

bDisorders of eating that do not fit criteria for other categories.

The main disorders that can have life-threatening health complications are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; they affect mainly females.

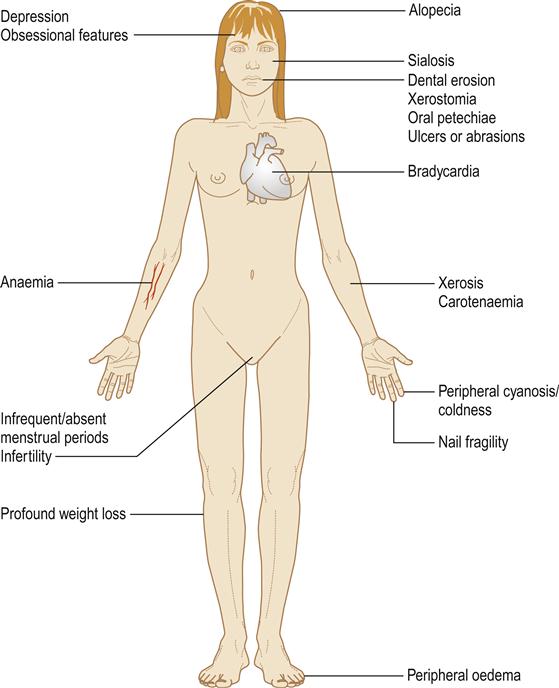

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is failure to eat, in the absence of any physical cause, to the extent that more than 15% of body weight is lost. It has several complications and may become life-threatening (Fig. 27.3). Body image may be distorted, so the emaciated patients consider themselves normal or even fat. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight, with resistance to maintaining body weight at or above a minimally normal for age and height, is prominent (Box 27.4). Disturbance in body image, the way in which the body weight or shape is perceived, undue influences of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight, obsession in the process of eating and development of unusual habits are common. Examples include avoiding food and meals, picking out a few foods and eating these in small amounts, pushing food around the plate instead of eating, or carefully weighing and portioning food. Anorectics may repeatedly check their body weight, despite severe weight loss (Fig. 27.4). Engaging in techniques to control weight, such as intense and compulsive exercise, purging by means of vomiting, or abuse of laxatives, enemas, appetite suppressants, diuretics and thyroid hormones, is common.

Severely thin limbs.

Girls with anorexia often experience a delayed onset of the first menstrual period, since gonadotropin release is impaired. In others, periods may become infrequent or cease. Depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder and self-harming are common. Growth may be impaired. Anorexia nervosa may be complicated by anaemia, endocrine disturbances, peripheral oedema and electrolyte depletion (hypokalaemia), peripheral cyanosis and coldness with bradycardia (see Table 27.5).

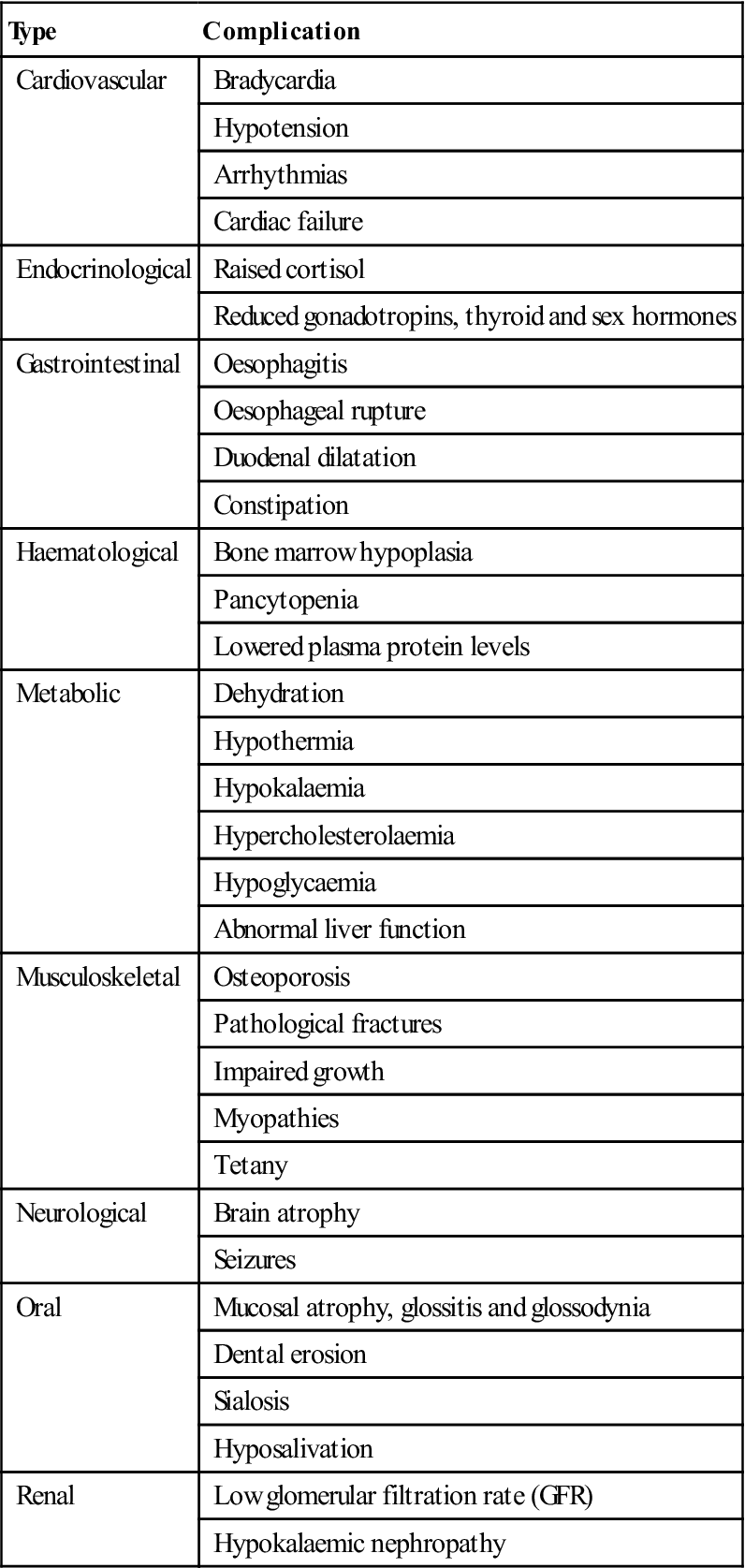

The course and outcome of anorexia nervosa vary. Some sufferers recover fully after a single episode; some have a fluctuating pattern of weight gain and relapse; and others experience a chronically deteriorating course over many years. The morbidity is high (Table 27.6) and mortality rate is about 12 times increased, cardiac arrest, electrolyte imbalance or suicide being the main causes.

Table 27.6

Medical and oral complications of anorexia nervosa

< ?comst?>

| Type | Complication |

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia |

| Hypotension | |

| Arrhythmias | |

| Cardiac failure | |

| Endocrinological | Raised cortisol |

| Reduced gonadotropins, thyroid and sex hormones | |

| Gastrointestinal | Oesophagitis |

| Oesophageal rupture | |

| Duodenal dilatation | |

| Constipation | |

| Haematological | Bone marrow hypoplasia |

| Pancytopenia | |

| Lowered plasma protein levels | |

| Metabolic | Dehydration |

| Hypothermia | |

| Hypokalaemia | |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Abnormal liver function | |

| Musculoskeletal | Osteoporosis |

| Pathological fractures | |

| Impaired growth | |

| Myopathies | |

| Tetany | |

| Neurological | Brain atrophy |

| Seizures | |

| Oral | Mucosal atrophy, glossitis and glossodynia |

| Dental erosion | |

| Sialosis | |

| Hyposalivation | |

| Renal | Low glomerular filtration rate (GFR) |

| Hypokalaemic nephropathy |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is recurrent episodes of binge-eating, which may be associated with compensatory behaviours such as self-induced vomiting and purgative abuse. The binge-eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours are practised, on average, at least twice a week for 3 months. Features include irresistible craving for food, characterized by eating an excessive amount within a discrete period of time and by a sense of lack of control over eating during the episode. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviour in order to prevent weight gain is common, and may include self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas or other medications (purging), fasting or excessive exercise. Bulimics often perform their behaviours in secrecy, feeling disgusted and ashamed when binging, and relieved once they purge.

Bulimics usually weigh within the normal range for their age and height but, like individuals with anorexia, may fear gaining weight, desire to lose weight and feel intensely dissatisfied with their bodies (Box 27.5).

General management of eating disorders

Eating disorders are serious conditions with a high co-morbidity and a poor prognosis: only 30–50% make a full recovery. Acute management of severe weight loss (BMI<13) is usually provided in hospital, where medical care and monitoring are needed to try to restore healthy eating and deal with the underlying emotional/psychological issues (by cognitive behavioural or interpersonal psychotherapy, nutritional counselling and, when appropriate, medication). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be helpful for weight maintenance and for resolving mood and anxiety symptoms.

Dental aspects of eating disorders

Repeated doses of paracetamol (acetaminophen) may be hepatotoxic in anorexia nervosa; doses should be kept to the minimum. Anaemia and the possibility of hypokalaemia and consequent arrhythmias must be kept in mind if GA is considered necessary.

Oral manifestations (see Table 27.6) can include erosion of teeth (perimylolysis) after repeated vomiting, usually most severe on lingual, palatal and occlusal surfaces. The patient should be counselled about diet and oral hygiene, what drinks and foods to avoid (Table 27.7) and how to reduce further erosion (e.g. by drinking colas and fruit juices through a straw). There is no evidence that tooth-brushing is harmful to eroded teeth, even soon after taking a drink of low pH. Topical bicarbonate after each vomiting incident, combined with daily sodium fluoride gel applications or a 0.05% sodium fluoride mouthwash, may lessen dental damage. Desensitizing toothpaste may also be indicated. Full-coverage plastic splints may be needed to protect the teeth and it may help to fill these splints with magnesium hydroxide. Restorative care may include dentine-bonded resins or composites, crowns or use of a Dahl appliance.

Table 27.7

Management of patients with tooth erosion

| Minimize tooth exposure to dietary acids | Increase oral pH | Caries protection |

| Reduce carbonated drinks, fruit juices, vinegar, alcohol | Mouth rinses of water, milk or bicarbonate | Non-cariogenic diet |

| Use a straw to drink low-pH fluids where feasible | Chewing gum | Fluorides |

| Plaque control |

Parotid enlargement (sialosis) and angular stomatitis may develop, as in other forms of starvation. The parotid swellings tend to subside if the patient resumes a normal diet. Oral ulcers or abrasions, particularly in the soft palate, may be caused by fingers or other objects used to induce vomiting.

Pica

Pica is a condition in which the appetite is perverted. It is seen mainly in persons with learning disability or mental health issues, but is sometimes due to pregnancy or iron deficiency. Many unusual objects and substances may be ingested, such as buttons, screws, pins, nails, etc., and some may cause gastrointestinal obstruction or perforation (Fig. 27.5). In the past, children sometimes chewed painted objects and succumbed to lead poisoning, which still occurs in the developing world.

Undernutrition

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses