Age and gender issues

Either Gender

Children

In the UK, people up to the age of 16 years are regarded as children. It may be necessary to take at least part of the history from a parent.

General aspects

At birth the neonate is classified as premature or preterm (less than 37 weeks’ gestation), full-term (37–42 weeks’ gestation) or post-dates (born after 42 weeks’ gestation). Premature babies are at particular risk from a number of problems.

Premature babies

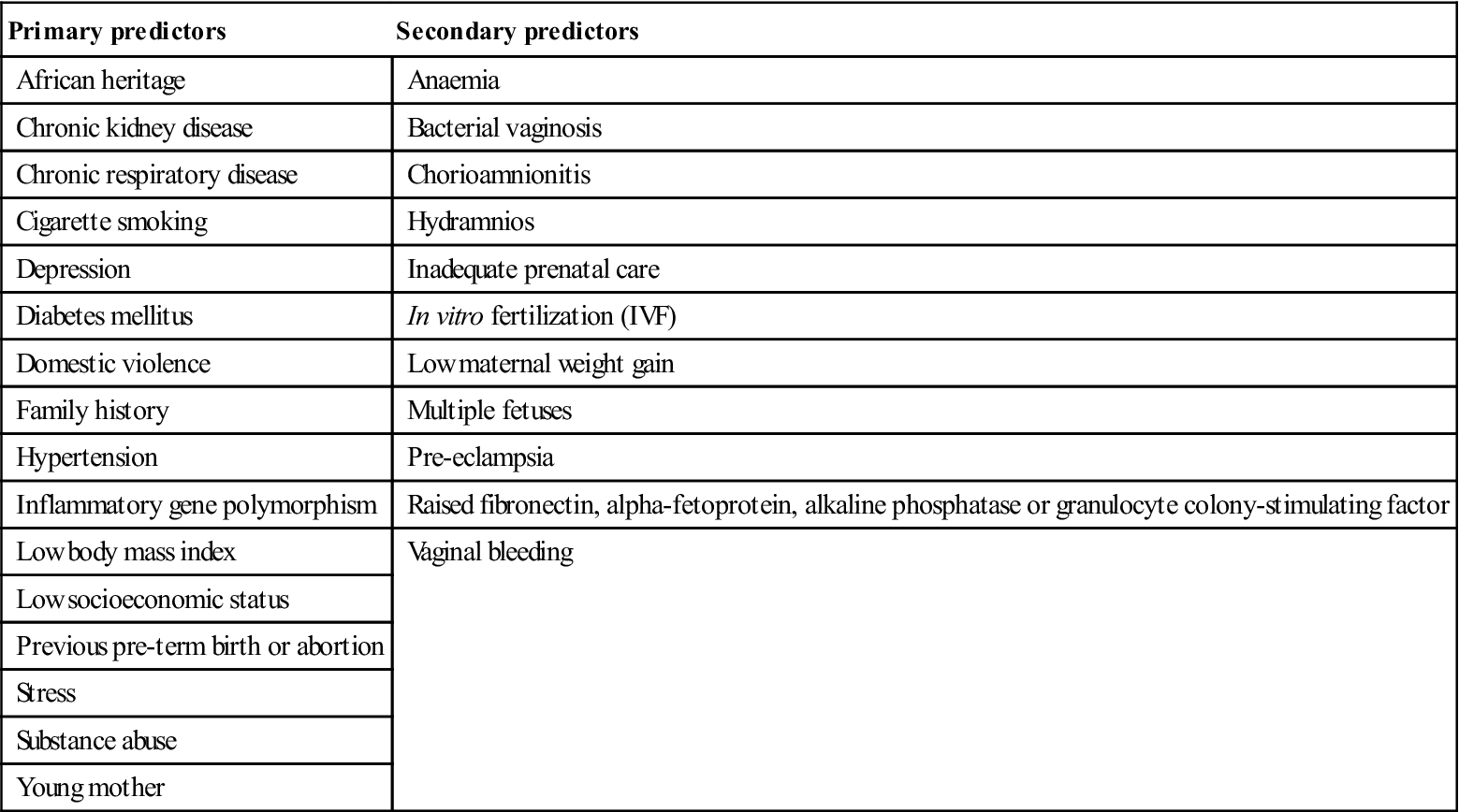

Up to 10% of all births are preterm, usually with a low birth weight (below 2500 g). Low birth weight may result from intrauterine growth retardation. Causes include multiple pregnancy, infection, maternal smoking, pre-eclampsia, severe anaemia, and heart and renal disease. These babies may go on to have lower IQs and smaller stature. In about 40% the cause is unknown but may be related to maternal issues: that is, elective delivery due to pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia (maternal hypertension, fluid retention and proteinuria) or placenta praevia (low-lying placenta). Maternal periodontal infection may possibly be a risk factor. Predictors are shown in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1

< ?comst?>

| Primary predictors | Secondary predictors |

| African heritage | Anaemia |

| Chronic kidney disease | Bacterial vaginosis |

| Chronic respiratory disease | Chorioamnionitis |

| Cigarette smoking | Hydramnios |

| Depression | Inadequate prenatal care |

| Diabetes mellitus | In vitro fertilization (IVF) |

| Domestic violence | Low maternal weight gain |

| Family history | Multiple fetuses |

| Hypertension | Pre-eclampsia |

| Inflammatory gene polymorphism | Raised fibronectin, alpha-fetoprotein, alkaline phosphatase or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| Low body mass index | Vaginal bleeding |

| Low socioeconomic status | |

| Previous pre-term birth or abortion | |

| Stress | |

| Substance abuse | |

| Young mother |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Preterm babies, depending on the degree of prematurity, may suffer apnoea or irregular breathing, a weak cry, inactivity, ineffective sucking and swallowing (with poor feeding), shiny wrinkled skin with fine body hair (lanugo), soft, flexible ear cartilage, enlarged clitoris (female) or a small scrotum (male). Preterm babies are less able to maintain body temperature and haemostasis, and are prone to several health consequences (Table 25.2). Up to a half suffer long-term sequelae, including low IQ, behavioural disorders, coordination problems, and respiratory and feeding problems.

Table 25.2

Possible consequences of preterm birth

| Early | Long-term |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) | Attention deficit disorder |

| Hypocalcaemia | Cerebral palsy |

| Hypoglycaemia | Hearing impairment |

| Intraventricular brain haemorrhage or periventricular infarction | Learning impairment |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | Retinopathy |

| Neonatal jaundice | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | |

| Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS; hyaline membrane disease) | |

| Sepsis |

Neonates

A neonate is a newborn infant up to 1 month old. Neonate behaviour is characterized by six states of consciousness: quiet sleep, active sleep, drowsy waking, quiet alertness, fussing and active crying. The amount a healthy infant cries in the first 3 months varies from 1 to 3 hours a day. Periodic breathing is normal. Temperature control, skin colour, stooling, yawning, gagging, hiccoughing, vomiting and sleep are easily affected by stress and stimulation. Sleep/wake cycles occur in random intervals of 30–50 minutes and gradually increase as the child matures. By 4 months old, most infants will have one long period of uninterrupted sleep and breathing stabilizes. The neonate can see objects within a range of 8–12 inches, has excellent colour vision, can track moving objects up to 180° and sees faces. Infants prefer the frequencies of the human voice. Senses of hearing, touch, taste and smell are mature at birth. Vestibular senses are also mature and the infant responds to rocking and changes of position.

During the neonatal period, most congenital defects (e.g. congenital heart disease) are detected. Congenital infections (e.g. rubella, herpesviruses, toxoplasmosis) may manifest. Immunological immaturity predisposes to candidosis. Infections may be transmitted by parents or carers, or from the environment; even tongue spatulas can be a source of infection.

This is a period of rapid growth and development. Facial, skull, jaw and tooth development can be impaired by radiotherapy, chemotherapy and some immunosuppressants during this time. Oropharyngeal or orogastric intubation may result in palatal grooving, acquired cleft palate and damage to the deciduous dentition. Appliances can be constructed to protect against this damage.

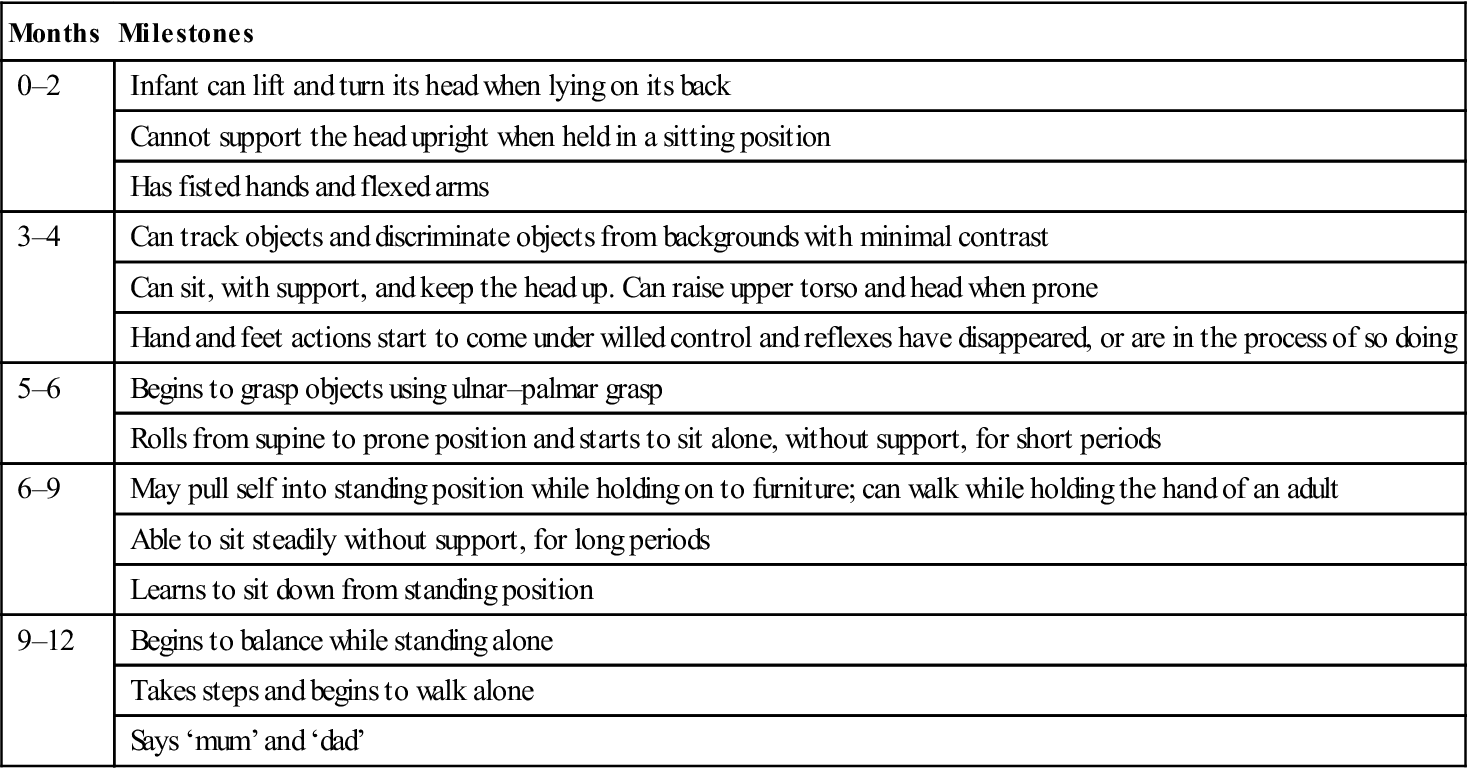

Infants

The first year of life is referred to as infancy. The healthy infant possesses a number of primitive reflexes (Table 25.3). Physical development begins at the head and then progresses to other parts (sucking precedes sitting, which precedes walking). Mental and neurological functions develop, with gross motor (e.g. head control, sitting, walking), fine motor (e.g. holding a spoon, pincer grasp), sensory, language and social development. There are several recognized ‘milestones’ in development, as shown in Table 25.4.

Table 25.3

| Reflexes | Composition |

| Babinski reflex | Toes fan when sole of foot is stroked |

| Moro reflex | On momentarily releasing head from a supported sitting position, arms abduct, hands open and then arms adduct |

| Palmar hand grasp | Closure over finger |

| Plantar grasp | Flexion of toe and forefoot |

| Rooting and sucking | Turns head in search for nipple when cheek is touched and begins to suck when nipple touches lips |

| Stepping and walking | Takes brisk steps when both feet placed on a surface, with body supported |

| Tonic neck response | Leg extends on side of head direction, flexion occurs in opposite arm and leg |

Table 25.4

Developmental milestones in infancy

< ?comst?>

| Months | Milestones |

| 0–2 | Infant can lift and turn its head when lying on its back |

| Cannot support the head upright when held in a sitting position | |

| Has fisted hands and flexed arms | |

| 3–4 | Can track objects and discriminate objects from backgrounds with minimal contrast |

| Can sit, with support, and keep the head up. Can raise upper torso and head when prone | |

| Hand and feet actions start to come under willed control and reflexes have disappeared, or are in the process of so doing | |

| 5–6 | Begins to grasp objects using ulnar–palmar grasp |

| Rolls from supine to prone position and starts to sit alone, without support, for short periods | |

| 6–9 | May pull self into standing position while holding on to furniture; can walk while holding the hand of an adult |

| Able to sit steadily without support, for long periods | |

| Learns to sit down from standing position | |

| 9–12 | Begins to balance while standing alone |

| Takes steps and begins to walk alone | |

| Says ‘mum’ and ‘dad’ |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

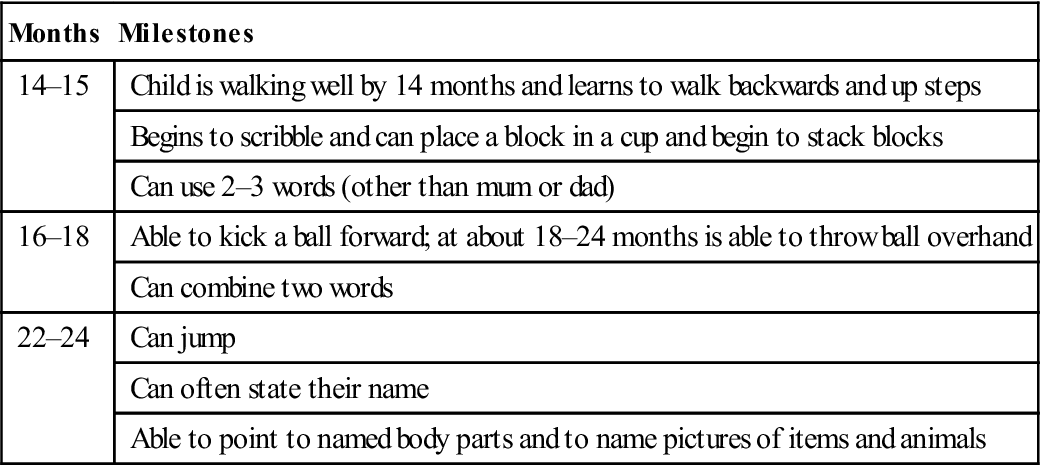

Children from 1 year (pre-school children)

Development proceeds with gross motor development recognized by milestones (Table 25.5), as the child becomes able to stand alone, stoop, pick something up and recover to standing (toddler). Young children strive constantly for independence, creating not only special safety concerns, but also discipline challenges.

Table 25.5

Developmental milestones in early (pre-school) childhood

< ?comst?>

| Months | Milestones |

| 14–15 | Child is walking well by 14 months and learns to walk backwards and up steps |

| Begins to scribble and can place a block in a cup and begin to stack blocks | |

| Can use 2–3 words (other than mum or dad) | |

| 16–18 | Able to kick a ball forward; at about 18–24 months is able to throw ball overhand |

| Can combine two words | |

| 22–24 | Can jump |

| Can often state their name | |

| Able to point to named body parts and to name pictures of items and animals |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Children aged 5–12 years (schoolchildren)

School-age children typically have fairly good gross motor skills, but there is wide variance in coordination, endurance, balance, physical tolerance and fine motor skills. They are usually able to use simple, complete, short sentences consistently. Receptive language skills necessary to understand long or complex instructions and the use of increasingly complex sentences develop. Delayed language development may indicate hearing or learning impairment. The attention span increases from about 15 minutes in 5-year-olds to about an hour by the age of 10. By about 10 years old, most children can follow five commands in a row. Reduced attention may herald attention deficiency.

Puberty

Puberty refers to the physical and psychological changes during maturation into an adult capable of reproduction. Manifest by the development of secondary sexual characteristics, it begins between 9 and 16 years of age, but children vary as to exactly when. On average, girls enter puberty 2 years earlier than boys.

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland hormones that control growth and maturation trigger rapid growth at puberty, with increases in height and weight, the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics and increased sexual interest (‘sex drive’). Oil glands become more active and acne may appear. Sweat glands become more active and produce more of an odour.

In girls, the ovaries begin to increase oestrogen production (along with other ‘female’ hormones). Girls experience rapid growth in height and increased hip width, breast enlargement, pubic, axillary and leg hair growth and vaginal secretions, followed by the onset of menstrual periods (menarche). The ovaries begin to release ova that, over 3 or 4 days, travel along Fallopian tubes to the uterus. Meanwhile, the endometrium (uterine lining) thickens by filling with blood and fluid. If the ovum is not fertilized, it dissolves and the endometrium sloughs, causing menstruation (menses). Menstrual cycles occur over about 1 month (28–32 days) and may be irregular initially. There may also be cyclical hormonal and physical changes, such as emotional or depressive reactions – the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) – and cramping menstrual pain. In girls, full physical maturation is usually complete by age 17, but educational and emotional maturity is ongoing.

In boys, the testicles increase testosterone production so that puberty usually occurs between 13 and 15 years of age. The pubescent boy experiences accelerated growth, especially in height, shoulder width and growth of penis and testicles, voice changes and growth of pubic, beard and axillary hair. Sperm is manufactured constantly in the testes (a process termed spermatogenesis) and is stored in the epididymis. This is released following masturbation or sexual intercourse, or during sleep – when it is known as a nocturnal emission or a ‘wet dream’.

Adolescence

Adolescence refers to the transition from child to adult, between 13 and 19 years of age. As well as sexual maturation, there are psychological changes resulting in emotional, behavioural and social changes. Specific health concerns for this age group are shown in Box 25.1.

General management

Children rely on parents for protection from harm and for discipline. Accidents are the major cause of morbidity and mortality; children are at increased risk because of a need for strenuous physical activity, a desire for peer approval and increased adventurous behaviour. Continued emphasis upon wearing seatbelts remains the single intervention most capable of preventing major injury or death due to a motor vehicle accident. Children should be taught to play sports in appropriate, safe and supervised areas, with proper equipment and rules, and with safety equipment (such as a bicycle helmet and other safety helmets; knee, elbow, wrist pads/braces, etc.; Chs 24 and 33). Safety instructions regarding contact sports, vehicle use, swimming and water sports, matches, fires, lighters and cooking are important to prevent accidents.

Dental aspects

Care of children is discussed fully in textbooks of paediatric dentistry. Important issues include consent; the treatment of trauma, caries and malocclusion; and issues related to anaesthesia and sedation.

Informed consent can be difficult to ensure in children too young to understand but conversely may be possible in some children under age 16 (Gillick competence). Children may present behavioural challenges in dental treatment; relative analgesia and local anaesthesia (LA) may be difficult or impossible to administer to some. Some drugs are contraindicated in childhood (Table 25.6). Children may also have some unusual reactions to drugs, such as diazepam and intravenous anaesthetics.

Table 25.6

Drugs that may be contraindicated in children

| Drug contraindicated | Possibility of |

| Antidepressants | Suicide attempts |

| Aspirin (salicylates) | Reye syndrome |

| Codeine | Respiratory depression |

| Diazepam | Paradoxical reactions |

| Kaopectate | Reye syndrome |

| Promethazine | Drowsiness and respiratory depression |

| Propofol | Propofol syndrome |

| Tetracyclines | Tooth discolouration |

Drug doses should be checked in the paediatric British National Formulary or equivalent, and adjusted for weight as necessary. Drug doses must be lowered for children and sugar-free preparations used.

After the eruption of the teeth, drugs that cause hyposalivation and procedures such as radiotherapy involving the salivary glands predispose to caries, especially in children. Preventive dental care and dietary counselling are of crucial importance.

Lengthening survival rates of premature infants have revealed several long-term sequelae, including orofacial defects. Some 20–55% have enamel hypoplasia, compared with 2% of controls, caused by birth trauma, infections and metabolic or nutritional disorders. Calcium disturbances are also common. Laryngoscopy can damage the unerupted maxillary anterior teeth and intubation with an oropharyngeal tube can cause grooving of the anterior maxillary ridge. The latter has few serious consequences.

Disturbed orofacial development can result from a range of causes in childhood, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, drugs, infections or toxins. Disturbed odontogenesis can have similar causes. Children may also be the subjects of abuse, resulting in orofacial and other injuries.

Child Abuse (Battered Child Syndrome; Non-Accidental Injury, NAI)

General aspects of abuse are also discussed in Chapter 24.

General aspects

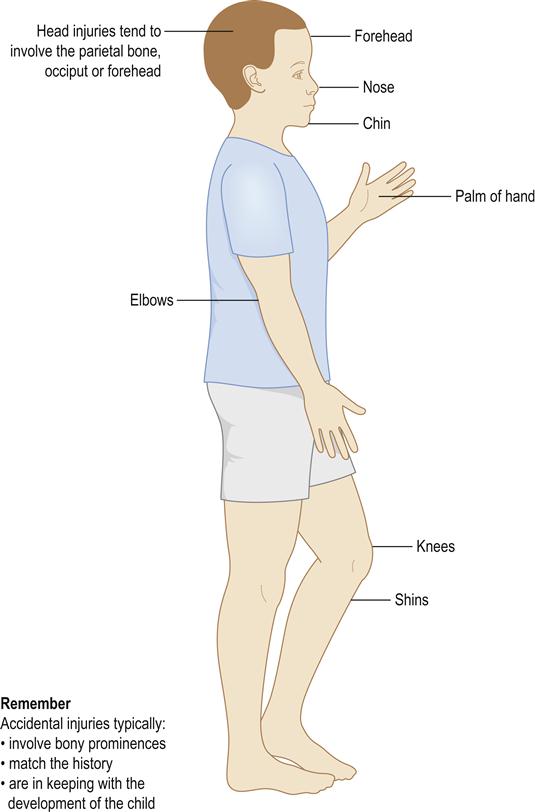

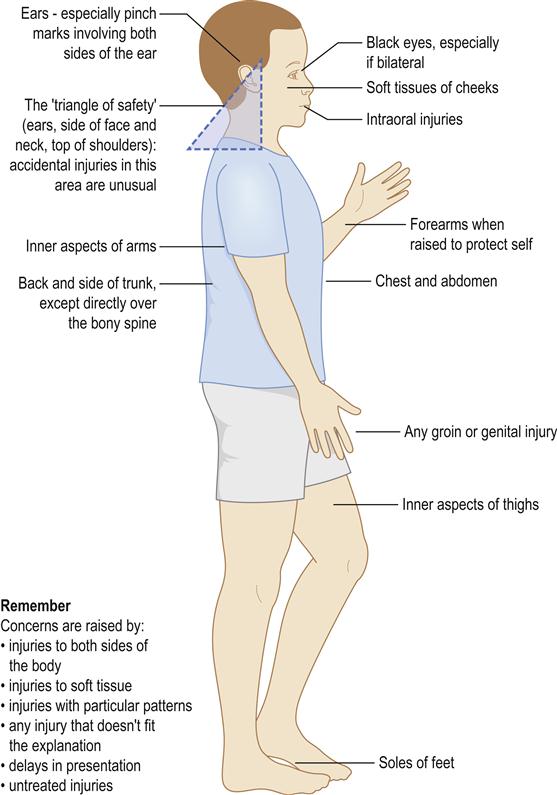

Up to 50% of children sustain injuries to their mouth by the time they leave school – mostly from accidents. The head and face are also the areas most commonly affected in physical abuse, however; they are involved in 65% of cases (Figs 25.1 and 25.2).

Child abuse is any act of omission or commission that endangers or impairs the physical or emotional health or development of a child. The threshold beyond which actions or omissions become abusive or neglectful is, to a certain extent, socially and culturally defined. A child is considered to be abused if he or she is treated in a way that is unacceptable in a given culture at a given time. For example, physical punishment of children has become progressively less acceptable in the UK.

Abuse and neglect are described in four categories, as defined in the UK Department of Health’s document ‘Working Together to Safeguard Children’; these are physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse and neglect. Some level of emotional abuse is involved in all types of ill-treatment of a child, though it may occur alone. Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately causes, illness in a child.

Abused children are usually below 1 year of age; most are less than 3. The injuries are usually inflicted by an adult, usually a parent, parent’s partner or an older sibling, and affected families are predominantly of socioeconomic classes IV and V. Causal factors may be related either to the parent, to social factors or to the child – and often all three (Table 25.7). Young or single parents, parents with learning difficulties, those who themselves have experienced adverse childhoods and those with mental health problems (including drug or alcohol abuse) are all more at risk of abusing their children. The assaulter may be supported by an inactive partner. Families living in adverse social environments – for example, due to poverty, social isolation or poor housing – may also find it both materially and socially harder to care for their children.

Table 25.7

Non-accidental injury: associated factors

| Parental | Social | Child |

| Marital disharmony | Poor housing | Abnormal pregnancy or delivery |

| Emotionally deprived, abused themselves | Poverty | Neonatal separation |

| Chronic physical illness | Social isolation | Being unwanted |

| Low intelligence | Hyperactivity, illness or aggression | |

| Young age or single parents | Being a stepchild | |

| Drug/alcohol dependence | Age below 1 year | |

| Mental disorders |

Children with disabilities are much more at risk of experiencing abuse of all kinds.

Clinical features

Recognition of child abuse is important since there is a very high risk of further assaults on, or death of, the child and of siblings; some 35–60% of physically abused children suffer further injury, with a 5–10% mortality rate. The child who has been subjected to abuse is often cowed, and may also be malnourished and generally neglected; there may be evidence of previous trauma. Psychological trauma from abuse can result in sleep disturbances, eating disorders, developmental growth failure in young children, and nervous habits such as lip- and fingernail-biting and thumb-sucking. Effects may also include chronic underachievement at school and poor peer relationships. In abusive families, physical neglect is commonplace, with inadequate provision of basic needs, including medical and oral health care; there may well be delay in seeking care (Box 25.2). Some suffer significant neurological, intellectual or emotional damage.

The injuries in child abuse can be varied and are often multiple, including bite marks (Ch. 24), bruises, black eyes, torn frenulum, hair loss, laceration, wheals, ligature marks, marks from a gag, burns and scalds, often from cigarettes or demarcated from other objects. Lacerations of the upper labial mucosa and tearing of the lip from the gingiva are found in about 45% of victims but are not diagnostic of child abuse.

Teeth may be devitalized, broken or lost. Bone fractures are common – mainly affecting ribs or long bones – but the skull and jaws can also be fractured. Head injuries are the commonest cause of death in abused children.

General management

After genuine accidents, children are usually taken immediately for medical or dental attention but, when children are abused, there is often considerable delay. Child abuse should also be suspected if any injuries are incompatible with the history and if any of the features in Box 25.2 are noted. Health-care professionals are obliged to know and follow the local child protection procedures (http://www.cpdt.org.uk/; accessed 30 September 2013). Full records must be kept. The child must be examined fully and immediately to exclude serious injury, especially subdural haematomas or intraocular bleeding, and must therefore be admitted to hospital. A skeletal radiographic survey should be undertaken to reveal both new and old injuries (osteogenesis imperfecta may need to be excluded). All injuries, including those to facial and oral tissues, must be carefully recorded, preferably with photographs.

Patients should be kept in hospital until the diagnosis is confirmed, since there is a high risk of further injury, which may be fatal. A paediatrician should be consulted and the general medical practitioner, social services and a child protection agency must be involved early on, but strict confidentiality must be observed. Social services departments keep registers of non-accidental injuries, which help identify known offenders. The child may already be on the ‘at-risk’ register. Dentists should also inform their medical defence society, as there may later be legal involvement.

Dental aspects

Orofacial lesions are common. Abuse or neglect may present in a number of different ways, such as through a direct allegation (sometimes termed a ‘disclosure’) made by the child, a parent or some other person; signs and symptoms that are suggestive of physical abuse or neglect; or observations of child behaviour or parent–child interaction.

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse can take many forms but, in addition to physical and psychological injury, the victim may also acquire one or more sexually transmitted infection, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse is more difficult to define and prove, but can manifest as development delay, failure to thrive, a watchful ‘radar’ gaze, behavioural problems and limited attention span.

Self-Inflicted (Factitious) Oral Lesions

See Chapter 10.

Older People

General aspects

Older people now account for some 15% of the UK population and this is set to increase. A growing proportion of the population, especially in developed countries, is over the age of 65 (a chronological criterion of ‘elderly’), with a rise in the proportion of older females, a significant number of whom are single (Fig. 25.3).

Many older people enjoy le troisième âge but, over the years, they are increasingly likely to need health care (Table 25.8). Up to 75% have one or more chronic diseases (30% have more than three), 11% are housebound, 8% walk with difficulty and some 3% are bedridden. Mobility is one of the major issues, and walking aids such as sticks, crutches and frames are commonly needed (Figs 25.4 and 25.5). Problems may be compounded if older people are from non-dominant populations (Fig. 25.6; see also Ch. 30). In the case of many older individuals, history taking can take considerable time; partners or care-givers may be able to help.

Table 25.8

Approximate number of years that older people are likely to be free from disability

| Age group | Men | Women |

| 65–69 | 9 | 11 |

| 70–74 | 7 | 9 |

| 75–79 | 5 | 7 |

| 80–84 | 3 | 5 |

| 85+ | 1 | 3 |

Medical problems

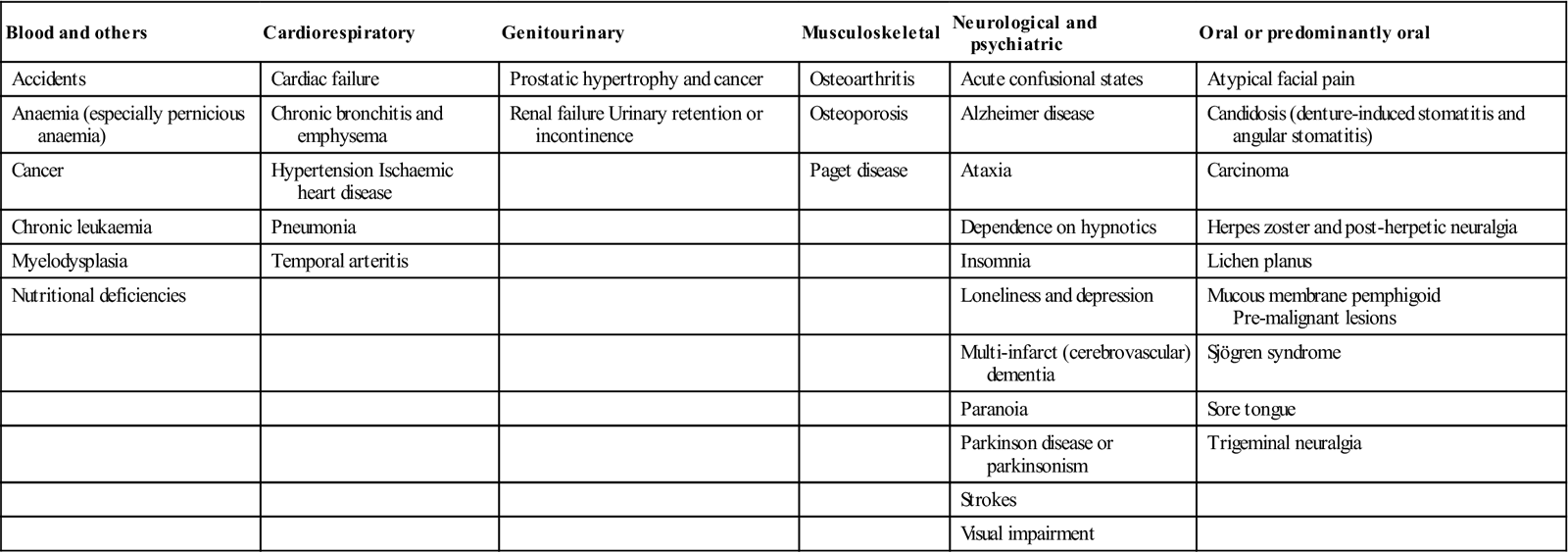

Many older patients have difficulty in accessing health care and some are reluctant to seek attention, especially if they fear consequent hospitalization. There is a greater incidence and severity of many diseases, especially arthritis and cerebrovascular disease, and these may cause ataxia and falls (Table 25.9). Alcohol related problems, mechanical and motor problems are important causes leading to falls among the elderly. Fractures and bruising may result, and senile purpura is common in many older people (Fig. 25.7). Defects of hearing or sight increase the liability to accidents, feelings of isolation and reduction of independence. The eyes may also show an arcus senilis (Fig. 25.8). Common causes of ataxia, faints and falls are visual impairment, transient cerebral ischaemic attacks, parkinsonism, postural hypotension (often drug-related), cardiac arrhythmias or ischaemic heart disease. Cancers are more common at advanced ages.

Table 25.9

Diseases especially affecting the older persona

< ?comst?>

| Blood and others | Cardiorespiratory | Genitourinary | Musculoskeletal | Neurological and psychiatric | Oral or predominantly oral |

| Accidents | Cardiac failure | Prostatic hypertrophy and cancer | Osteoarthritis | Acute confusional states | Atypical facial pain |

| Anaemia (especially pernicious anaemia) | Chronic bronchitis and emphysema | Renal failure Urinary retention or incontinence | Osteoporosis | Alzheimer disease | Candidosis (denture-induced stomatitis and angular stomatitis) |

| Cancer | Hypertension Ischaemic heart disease | Paget disease | Ataxia | Carcinoma | |

| Chronic leukaemia | Pneumonia | Dependence on hypnotics | Herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia | ||

| Myelodysplasia | Temporal arteritis | Insomnia | Lichen planus | ||

| Nutritional deficiencies | Loneliness and depression | Mucous membrane pemphigoid Pre-malignant lesions |

|||

| Multi-infarct (cerebrovascular) dementia | Sjögren syndrome | ||||

| Paranoia | Sore tongue | ||||

| Parkinson disease or parkinsonism | Trigeminal neuralgia | ||||

| Strokes | |||||

| Visual impairment |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Atypical symptomatology is common; physical disease may present in a less florid and dramatic way in older people. Temperature regulation may be so disturbed that respiratory, urinary or even more serious infections often fail to cause fever. Older patients also readily become hypothermic, especially if thyroid function is poor. Many disorders in older patients also present with non-specific features, such as general malaise, social incompetence, a tendency to fall and mild amnesia.

Dementia becomes increasingly common with age. If responses are slow, it may be caused by underlying physical disease, especially if the symptoms are of acute onset. A confusional state may result acutely from disorders as widely different as minor cerebrovascular accidents, respiratory or urinary tract infections, or left ventricular failure. Confusional states may be more chronic when caused by poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, carcinomatosis, anaemia, uraemia or drug therapy.

Social disabilities are common as a result of such causes as loss of the spouse, isolation from family, poverty, and lack of mobility and independence. Old people may need to be thrifty and careful with food purchasing and the heating of their accommodation, contributing to overall self-neglect. Nutrition may also be defective due to apathy, mental disease or dental defects. Malnutrition may, in turn, lead to poor tissue healing and predispose to ill-health. Deterioration in the senses of smell and taste may also result in a poor or unhealthy diet. Psychological disorders, such as loneliness and depression, may follow. Depression may also be a feature in hypothyroidism or a side-effect of medications.

Older people are more likely to be given medication and complications account for about 10% of admissions to geriatric units. Polypharmacy, abnormal reactivity towards many drugs, poor compliance, inappropriate treatment and deteriorating renal and other metabolic pathways affecting drug metabolism can result in toxicity and serious interactions. Older people tend to be more liable to adverse drug reactions, and the reactions tend to be more serious and last longer than in younger people.

Drugs may also precipitate or aggravate physical disorders that are more frequent in the older person. For example, drugs with antimuscarinic activity, such as atropine or antidepressants, may precipitate glaucoma, or may cause dry mouth or, if there is prostatic enlargement, urinary retention. Phenothiazines may precipitate or aggravate parkinsonism or hypotension, or may cause apathy, hypothermia, excessive sedation or confusion. Drowsiness, excessive sedation or confusional states may also be provoked by the benzodiazepines or tricyclic antidepressants, while depression and postural hypotension not uncommonly follow the use of hypotensive agents. Drugs should therefore be used cautiously (Table 25.10).

Table 25.10

| Problems | Possible solutions | |

| Analgesics | Sensitivity to their effects | Restrict dose |

| Dosage regimens | Difficulties remembering regimens | Simplify regimens and write clear instructions; use dosette boxes |

| Drug dose | Overdose from sensitivity to agents | Restrict dose |

| Form of medicine | Difficulty swallowing tablets | Take with water or use liquid preparations |

| Non-prescribed drugs | Self-medication without medical advice | Restrict drug availability |

| Psychotropics | Sensitivity to their effects | Restrict dose |

The capacity to carry out activities of ordinary life (dressing, eating, bathing, etc.) is assessed with specific tests: for example, the activities of daily living scale (ADLS) or Katz; based on this assessment, the older person is classified as functionally independent or dependent.

General management

Social support is crucial, preserving as much independence and dignity as possible.

Dental aspects

Many older people receive no dental attention whatsoever, despite much evidence of their need. It has been found in one study, for example, that 81% had oral lesions and 20% needed further investigation to exclude serious oral disease. Access to dental care can be a major difficulty for the person who is frail or has limited mobility. Handling of older patients may demand immense patience, but remember always to treat the older patient with sympathy and respect. It can take a long time for a patient in a wheelchair or using a Zimmer frame to get into the surgery and on to the dental chair. Domiciliary care may be more appropriate and avoids the physical and psychological problems of a hospital or clinic visit. Older people are often extremely anxious about treatment and should therefore be sympathetically reassured and, if necessary, sedated.

Mucosal lesions may be present in up to 40% of older people. Most of these are fibrous lumps or ulcers, but a minority are potentially or actually malignant lesions. Oral cancer is mainly a problem of older people and is a further reason for regular oral examination (Ch. 22). Atypical facial pain (often related to depressive illness), migraine, trigeminal neuralgia, zoster and oral dysaesthesias are more common as age advances.

Many older people with remaining teeth have periodontal disease. Dental caries are usually less acute but root caries are more common. Caries may become active if there is hyposalivation, especially if there is overindulgence in sweet foods. Hyposalivation is even more likely with medications such as neuroleptics or antidepressants (Ch. 10). Poor salivation may contribute to a high prevalence of root caries and oral candidiasis, which especially affect hospitalized patients.

Very many older patients are edentulous and some problems of dental management are thereby greatly reduced. It seems, however, that the proportion of edentulous older patients is gradually falling and, as a consequence, more of them need restorative dentistry or surgery of various types. Many edentulous older people have little alveolar bone to support dentures, and have a dry mouth as well as frail, atrophic mucosa. Implants may be helpful. Inability to cope with dentures, or a sore mouth for any reason, or being unable to afford appropriate care readily demoralizes the older patient, and may tip the balance between health and disease.

Food can become tasteless and unappetizing as the result of declining taste and smell perception. Older patients should be encouraged to add seasonings to their food instead of relying on excessive consumption of salt and sugar to provide flavour.

The dentist therefore has an important role in supporting morale and contributing to adequate nutrition. Handling of older patients may demand increased time and patience.

Sound teeth should be conserved if they can serve, at least for a few years, as abutments or retainers for prostheses. It may also be unwise to alter the shape or occlusion of dentures radically when they have been worn for years. It is wise to label the dentures with the name of the patient, particularly for those living in sheltered or other residential accommodation, as dentures can easily be mislaid or mixed up between patients.

Attrition and brittleness of the teeth may complicate treatment, and it may be necessary to provide cuspal coverage in complex or large restorations. Endodontic therapy may be more difficult in view of secondary dentine deposition. Hypercementosis, brittle dentine, low bone elasticity and impaired tissue healing may also complicate surgical procedures.

The major goals of oral health care are preventive and conservative treatment for conditions such as hyposalivation, root caries, secondary caries, periodontal disease and gingival recession, and the elimination/avoidance of pain and oral infections.

Independent people with no serious medical problems may be treated in primary dental care. Dependent people may need domiciliary dental care with portable dental equipment. When significant medical problems are present, the older person may be best seen in a hospital environment, though this raises issues of adequate transportation and availability of escorts.

Prevention is of paramount importance in caring for older adults. Therefore, the most important considerations for dental professionals are how well the patient has compensated for his or her medical problem and the exact dental intervention needed. Non-invasive procedures in patients with minimal incapacity carry less risk than do surgical procedures. Older people tend to be more sensitive to drugs and to trauma. Dental treatment planning may be conditioned by factors such as oral health status, capacity to move, motor and mental skills to follow a preventive programme, survival prognosis and economic resources. The whole range of dental treatments may be considered. Dental implants are not at all contraindicated, and they may help to maintain the remaining alveolar bone.

Appointment times may be conditioned by systemic diseases. Sympathetic reassurance is indicated and, if necessary, sedation, with short-acting benzodiazepines. Treatment is often best carried out with the patient sitting upright, as few like reclining for treatment and some may become breathless and panic. Dentists should recognize that older people, especially women, also heal slowly and bruise readily if tissues are not handled carefully.

To control pain and anxiety, dentists should use LA whenever possible, since the risks of using general anaesthesia (GA) are greater than in younger patients. LA used in recommended dosages has no effect on cardiac arrhythmias in the ambulatory older patient. Intravenous sedation in the dental chair is best avoided if there is any evidence of cerebrovascular disease, as a hypotensive episode may cause cerebral ischaemia. The risks of conscious sedation (CS) or GA are greater than in the young patient, not least because of associated medical problems. Relative analgesia is preferable to benzodiazepines for sedation, and benzodiazepines are preferable to opioids. GA may be necessary for patients unable to cooperate and those with dementia. After long operations, older patients are prone to pulmonary complications, such as atelectasis, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism; they may also become confused in an unfamiliar environment.

Polypharmacy should be avoided, not only because of the danger of drug interactions but also because of the practical difficulties that the patient may have in taking the correct doses at the correct times. Older people frequently have difficulties in understanding the medication and in remembering to keep to a regimen. Compliance may therefore be lacking. If there is hepatic or renal disease likely to impair drug metabolism or excretion, drug dosage must be reduced appropriately.

Abuse of Older People

Elder abuse occurs when an older person is harmed, mistreated or neglected (see also Ch. 24). There are five types of elder abuse: psychological abuse, physical abuse, financial abuse, sexual abuse and neglect (Box 25.3).

People who are being abused are often scared that they will not be believed. Those who witness or suspect abuse may not want to be seen as ‘interfering’ or may be scared of ‘getting it wrong’. If abuse is suspected, always talk to the ‘victim’ first and tell them what you want to do. The main charitable and government-sponsored organizations that can offer support to those affected include police, hospitals, general medical practitioners, carer organizations, social services/social work departments, and social care inspection bodies. Be clear about whether the person knows you are reporting your concerns; whether the older person is confused or lacks the capacity to make informed decisions about their life; who you think is being abused (name, address, age); and what you think is happening to that person. Give reasons/examples to illustrate why you think abuse is occurring. It helps if you can provide dates and times of incidents; what has been said; who you believe is responsible; and the relationship of that person with the older person.

See http://www.ageuk.org.uk/ (accessed 30 September 2013).

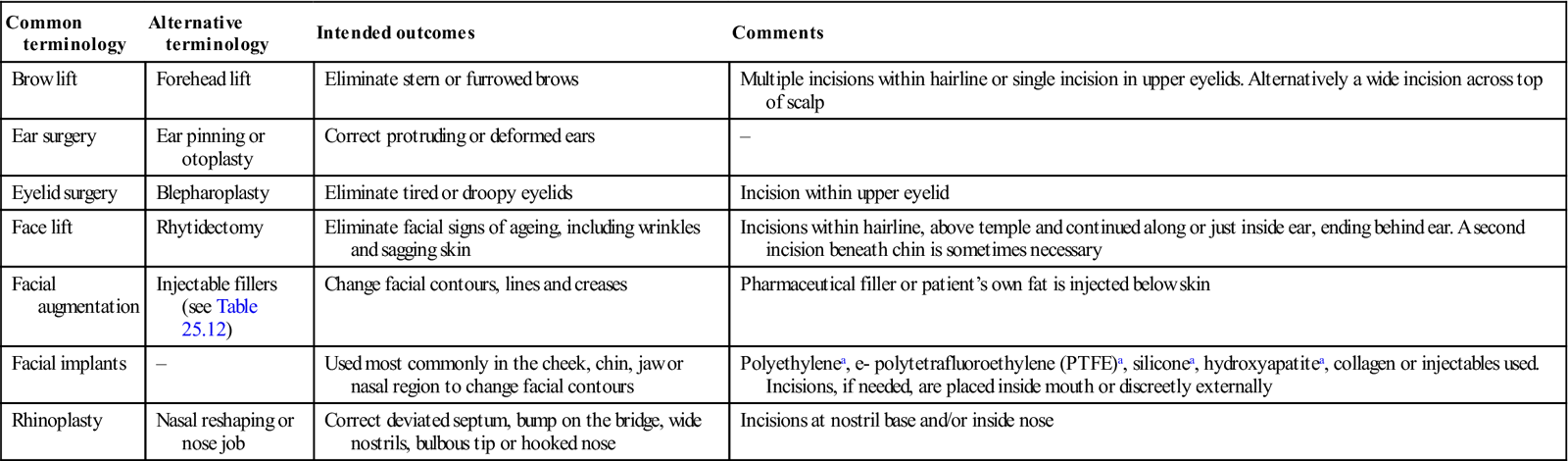

Facial Cosmetic Procedures

Cosmetic facial procedures are increasingly used by both genders and include injections of botulinum toxoid (Ch. 13); removal of unsightly skin lesions; laser resurfacing; chemical peeling; or orthognathic surgery – and a range of other procedures, some of which are shown in Table 25.11. These are often performed as outpatient procedures under local anesthesia with or without sedation but general anaesthesia may be used. Outcomes may include pain, swelling, bleeding and bruising and infection. The resultant changes in appearance typically persist for months or sometimes years, notably where non-resorbable materials have been used. More worrying are the do-it-yourself “cosmetic” procedures becoming popular for example in Korea.

Table 25.11

Facial cosmetic procedures other than use of orthognathic surgery or botulinum toxoid

< ?comst?>

| Common terminology | Alternative terminology | Intended outcomes | Comments |

| Brow lift | Forehead lift | Eliminate stern or furrowed brows | Multiple incisions within hairline or single incision in upper eyelids. Alternatively a wide incision across top of scalp |

| Ear surgery | Ear pinning or otoplasty | Correct protruding or deformed ears | – |

| Eyelid surgery | Blepharoplasty | Eliminate tired or droopy eyelids | Incision within upper eyelid |

| Face lift | Rhytidectomy | Eliminate facial signs of ageing, including wrinkles and sagging skin | Incisions within hairline, above temple and continued along or just inside ear, ending behind ear. A second incision beneath chin is sometimes necessary |

| Facial augmentation | Injectable fillers (see Table 25.12) | Change facial contours, lines and creases | Pharmaceutical filler or patient’s own fat is injected below skin |

| Facial implants | – | Used most commonly in the cheek, chin, jaw or nasal region to change facial contours | Polyethylenea, e- polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)a, siliconea, hydroxyapatitea, collagen or injectables used. Incisions, if needed, are placed inside mouth or discreetly externally |

| Rhinoplasty | Nasal reshaping or nose job | Correct deviated septum, bump on the bridge, wide nostrils, bulbous tip or hooked nose | Incisions at nostril base and/or inside nose |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

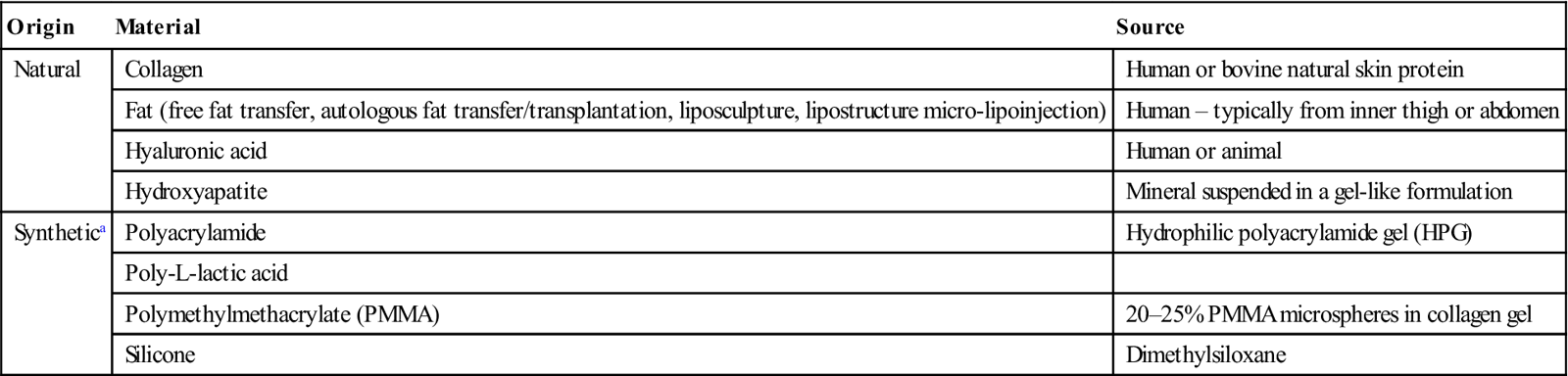

Fillers

Injectable fillers are an increasingly popular cosmetic procedure. Results are temporary, lasting a few months with natural products to several years when synthetic materials are used. Complications may include temporary pain, bleeding, bruising, swelling, seromas (fluid collections), infection or allergy; mainly with synthetic materials such as silicone, long-term granulomas/disfigurement are also possible. However, the existence of a so-called silicone immune toxicity syndrome is controversial.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews and approves pharmaceutical fillers in the same manner as medical devices. However, some fillers may be used on an off-label basis and injection of permanent substances (e.g. silicone) in particular poses safety issues such as granuloma formation (Table 25.12).

Table 25.12

< ?comst?>

| Origin | Material | Source |

| Natural | Collagen | Human or bovine natural skin protein |

| Fat (free fat transfer, autologous fat transfer/transplantation, liposculpture, lipostructure micro-lipoinjection) | Human – typically from inner thigh or abdomen | |

| Hyaluronic acid | Human or animal | |

| Hydroxyapatite | Mineral suspended in a gel-like formulation | |

| Synthetica | Polyacrylamide | Hydrophilic polyacrylamide gel (HPG) |

| Poly-L-lactic acid | ||

| Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) | 20–25% PMMA microspheres in collagen gel | |

| Silicone | Dimethylsiloxane |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Men’s Health

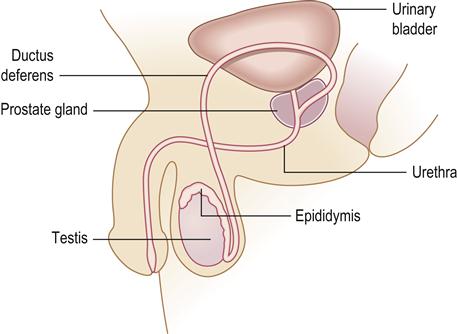

The male genitals include the testes, vas deferens, epididymis and penis, together with accessory structures – the prostate and bulbourethral glands. The testes, located in the scrotum, produce sperm cells and the hormone testosterone, which influences development of body shape and hair, and regulates spermatogenesis. The anatomy of the male genital system is shown in Figure 25.9. Disorders of the gonads are outside the remit of this text.

There are some conditions that affect only men and there are gender differences in regard to patterns of many diseases (Box 25.4). Men generally also access and use health care differently from women (typically less); generally, they are less likely to react to health promotion and are more likely to have lifestyle habits that are detrimental to their health (e.g. alcohol or drug abuse).

Balanitis (Balanoposthitis)

Balanitis is inflammation of the skin covering the glans penis. The most common cause is neglected hygiene and tight foreskin (phimosis), leading to irritation by smegma, but less common causes are shown in Box 25.5. Treatment depends on the underlying cause.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses