Bimaxillary Dental Protrusive Growth Patterns with Dentofacial Disharmony

• Orthognathic and Dentoalveolar Surgical Approaches

• Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing

• Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

• Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

Bimaxillary dental protrusion can occur in any racial group, but facial divergence (i.e., convexity) and lip prominence are strongly influenced by racial and ethnic characteristics.37,67,95,107 Greater degrees of lip and incisor prominence tend to occur in Asians, Africans, and Latinos as compared with Caucasians.68,75 In Caucasian populations, dental protrusion is more common among individuals of Mediterranean background than among those from more northern European regions. The Australian aborigines, who are classified as Caucasoid, have greater degrees of facial and dental protrusion. Etiologic factors that favor bimaxillary dental protrusion with anterior open bite include heredity; paraoral habits (e.g., thumb sucking); and the presence of strong protrusive tongue muscle forces in combination with weak bilabial (lip) forces.103,104,120 The common physical findings include flaccid lips, procumbent maxillary and mandibular incisors, and an anterior open bite.

Drummond compared the facial morphology of Caucasian Americans to that of African Americans.35 He found that Africans more frequently have a protrusive and strong tongue with loose, flaccid lips. These altered forces during growth are known to gradually push the anterior teeth into a procumbent position. The resulting proclination of the teeth in combination with the thickness of the lips make the lower face appear to be more full. Altemus compared the cephalofacial relationships of Caucasian, African, Chinese, Japanese, Navajo Indian, and Australian aboriginal individuals.3 He concluded that the relative straightness of an individual’s facial profile is very much a reflection of the underlying skeletal parts. He also found that, although the upper facial profiles (i.e., the forehead, orbits, and cheekbones) of the varied racial groups appeared to be remarkably similar, the lower facial profiles (i.e., the maxilla, mandible, and chin region) did not. The position of the anterior teeth and lips of African children were found to be more protrusive as compared with those of Caucasians. Sushner studied 100 lateral facial photographs of “attractive” Africans.119 He used the Steiner, Holdaway, and Ricketts cephalometric standards to analyze the “attractive” African facial photographs,53,88 and he concluded that the soft-tissue profiles of the individuals in those photographs were significantly more protrusive than the accepted Caucasian standards. He went on to establish African cephalometric norms. Similar studies completed by Guinn and Connor confirmed that the African soft-tissue profile is more protrusive and significantly different from Caucasian cephalometric norms.5,24,25,50

Peck and Peck set out to determine the public’s concept of beauty as related to the Caucasian profile.94 The authors found that the general public admires a more full face as compared with the accepted cephalometric normative data and clinical orthodontic standards of the day (e.g., four bicuspid extractions with orthodontic retraction). These authors pointed out that the “ultimate source of our aesthetic values should be the people [i.e., public opinion], not just ourselves [i.e., clinicians].” Foster studied facial aesthetic preferences among various groups by using profile silhouettes.44 The evaluators included Africans, Caucasians, and Chinese individuals; art students; general dentists; and orthodontists. The results confirmed a common aesthetic preference for the position of the lips in profile to be within 1 mm to 2 mm of each other. Another finding was that all groups consistently associated fuller lips with a more youthful appearance. Farrow and colleagues attempted to discover what African Americans find attractive about their own profiles.40 The study results found that the preferred aesthetic profile involved slight convexity and more protrusion as compared with standard Caucasian cephalometric norms. A review of the literature confirms that, as a group, African Americans differ from Caucasian Americans with regard to dental, skeletal, and soft-tissue facial parameters.2,31,43,58,122 For both groups, facial convexity is a preferred feature.28,30,76,77,100 However, the question remains: at what point does attractive fullness (i.e., convexity) of the profile become dysmorphic and unattractive?

Distorted vertical and horizontal growth of the maxillomandibular skeleton in association with bimaxillary dental protrusion will result in both facial and dental disharmony.84 This growth pattern may be associated with Class I, Class II, and Class III molar relationships, but it always occurs with mandibular and maxillary incisor procumbency and anterior open-bite malocclusion.5,47,52,85,113,118 Individuals with bimaxillary dental protrusion will also have varying degrees of lip incompetence and mentalis strain; exposure of the anterior teeth in repose and gingival show with smile; and, typically, a dysmorphic chin in profile. If these aspects become excessive, then the diagnosis of an associated dentofacial disharmony is appropriate.109

The generally offered correction of the anterior open-bite malocclusion associated with bimaxillary dental protrusion is the extraction of four premolars followed by the orthodontic retraction of the anterior teeth into the edentulous gaps.6,121,126 This treatment also tends to retract the lips and to reduce facial convexity.33,34,48,72 To determine which individuals also have significant dentofacial (jaw) disharmony and thus will benefit from an orthognathic approach (i.e., the surgical repositioning of the upper and lower jaws), the clinician should assess pretreatment skeletal, dental, and soft-tissue parameters. This includes the following:

• An evaluation of the maxillomandibular skeleton (i.e., horizontal and vertical dimensions)

• An assessment of the dental condition (i.e., incisor inclination, spacing and crowding, the curve of Spee, arch width, overjet, and overbite)

• An evaluation of the soft-tissue static and dynamic position of the lips (i.e., the lip-to-tooth relationship in repose and with smile, the interlabial gap, the degree of mentalis strain with closure, and the nasolabial and labiomental angles).

Functional Aspects

• Wide lip separation with excessive effort required to achieve lip seal is present.

• Chronic obstructive nasal breathing as a result of increased intranasal airway resistance is frequent (see Chapter 10).

• Classic articulation errors in speech caused by the anterior open-bite malocclusion are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Chewing and swallowing difficulties as a result of the anterior open-bite malocclusion and lip incompetence are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and the periodontium caused by traumatic occlusal forces, the spacing of the teeth in the alveolar housing, or previous camouflage orthodontic treatment may be seen (see Chapter 5 and 6).

• Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) should be looked for but is not generally problematic in these individuals (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• Separation of the lips at rest of >4 mm

• Excessive dental show with the upper lip at rest and excessive gingival show with a broad smile

• Flaccid lips with more effort required to bring them into closure (i.e., mentalis strain and lip incompetence)

• Excessive prominence of the lips with everted vermillion borders when viewed in profile

• Typically a mouth-breathing habit and an open-mouth posture with a protrusive tongue

Dental Findings

• Maxillary and mandibular incisor proclination

• Exaggerated curve of Spee in the maxilla and a reverse curve in the mandible

• Frequently with narrow maxillary arch width

• Frequently with a Class II molar relationship, although a Class I or Class III malocclusion may be present

• Frequently with interdental spacing in the anterior dentition of the maxilla and mandible

• Despite incisor proclination, presence of adequate periodontal support without gingival recession, labial bone dehiscence, or fenestration is typical

Treatment Pitfalls

When considering orthognathic surgery for the individual with bimaxillary dental protrusion, there must be a compelling aesthetic or functional rationale for the shortening of the anterior vertical dimension of the face and the alteration of the horizontal projection (Figs. 24-1 through 24-11).18,41,46,64,65,80,115 When present, facial aesthetic disharmony in association with bimaxillary dental protrusion is generally characterized by the following:

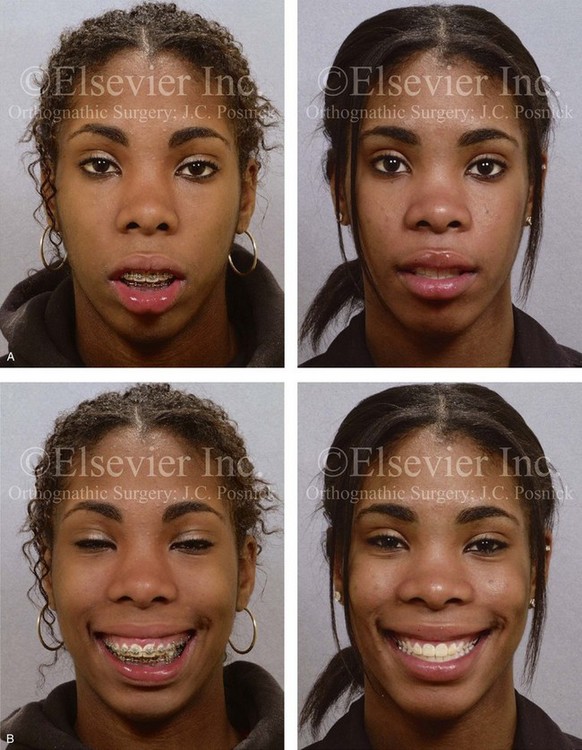

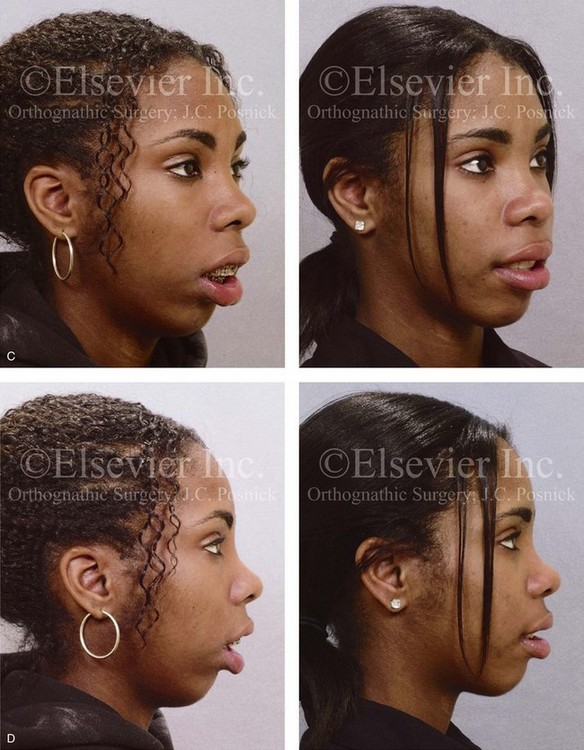

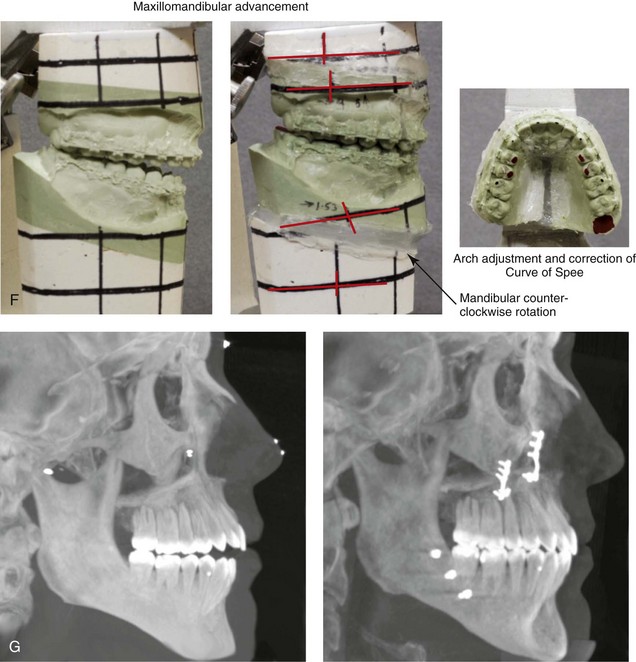

Figure 24-1 A 16-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for the evaluation of lip incompetence, anterior open bite, gummy smile, weak chin, and nasal obstruction. Orthodontics had previously been carried out without extraction therapy. The patient presented with a Class II anterior open bite dental protrusive malocclusion. A combined orthodontic and surgical approach was recommended. With non-extraction orthodontic decompensation complete, the patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (arch expansion, correction of the curve of Spee, vertical intrusion, minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

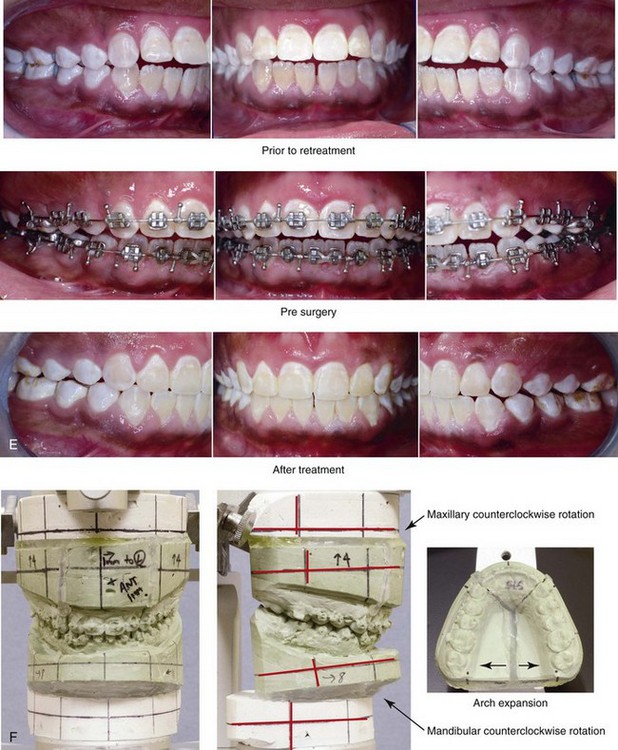

Figure 24-2 A 28-year-old woman arrived for the evaluation of malocclusion, gummy smile, lip incompetence, and nasal obstruction. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (transverse expansion, vertical intrusion, minimal advancement, and clockwise rotation); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, with orthodontics in progress, and 3 years after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

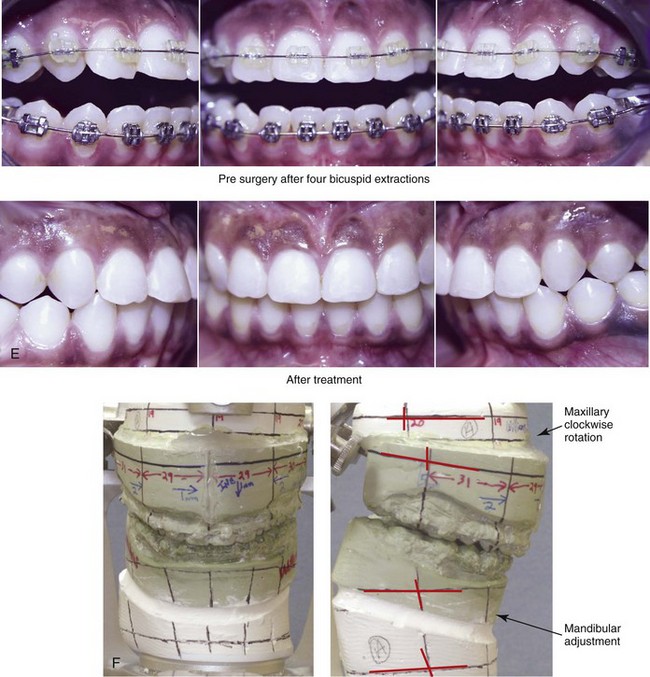

Figure 24-3 A 24-year-old woman was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent four bicuspid extractions with orthodontic decompensation followed by orthognathic surgery. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (clockwise rotation, horizontal advancement, arch expansion, and vertical shortening); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views with orthodontics in progress and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning.

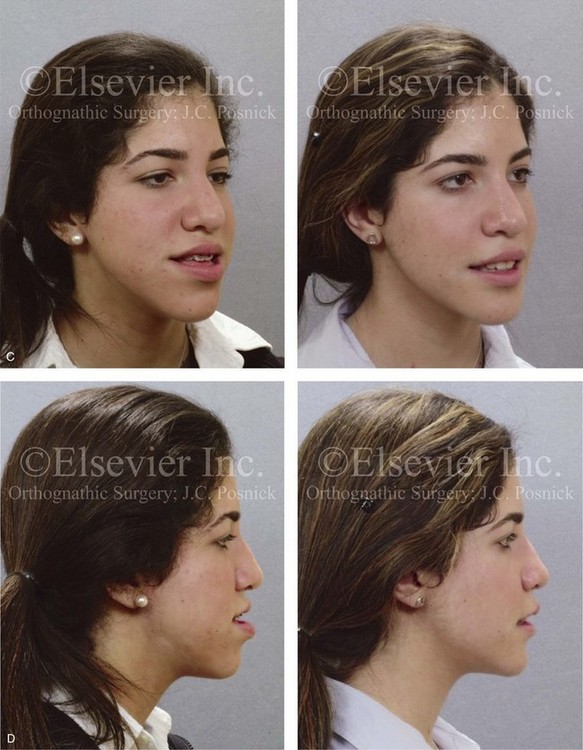

Figure 24-4 A 28-year-old Hispanic woman was referred by her orthodontist for the evaluation of malocclusion and lip incompetence. She was found to have a Class III anterior open-bite malocclusion and lifelong nasal obstruction. She underwent non-extraction orthodontic decompensation followed by surgery. Her procedures included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (correction of the arch form); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before orthodontics and after treatment. Note the limited overjet as a result of mild dental relapse. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

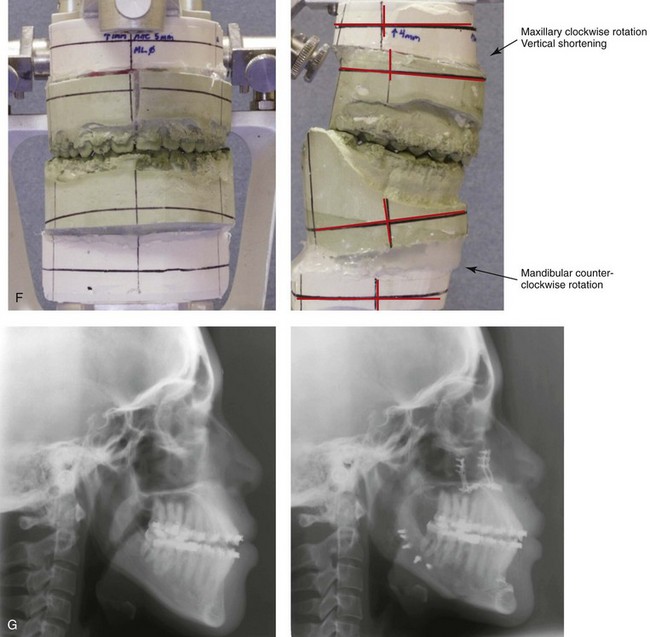

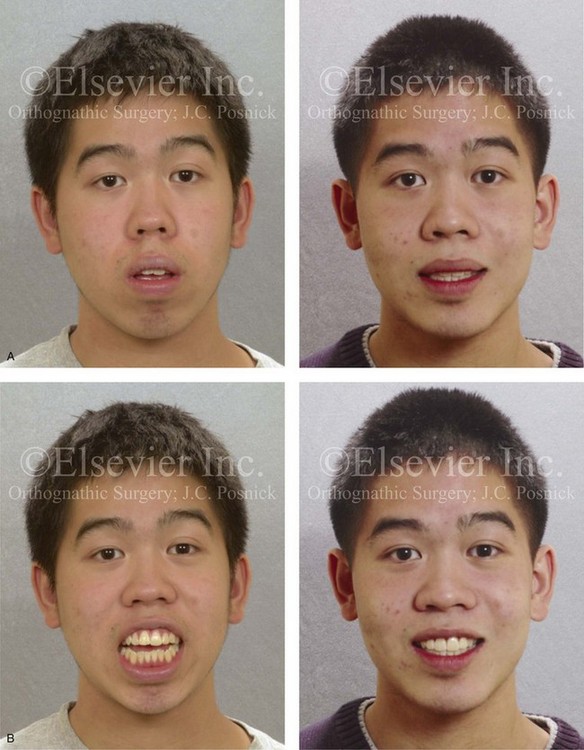

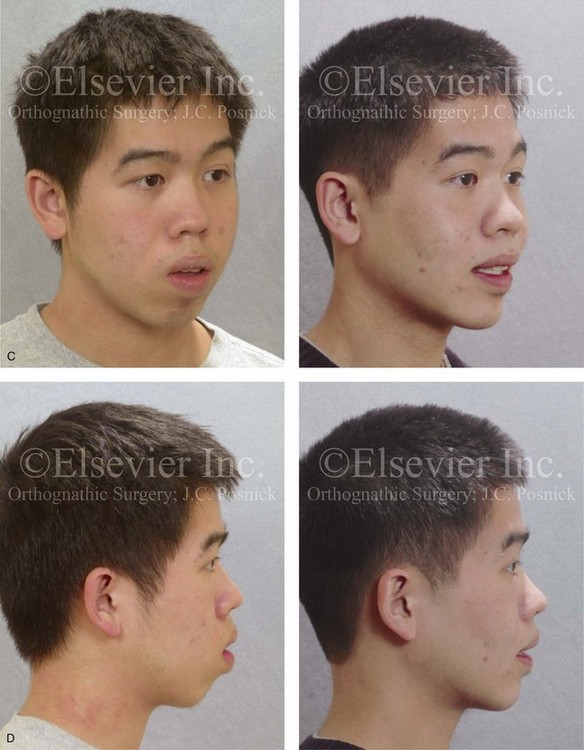

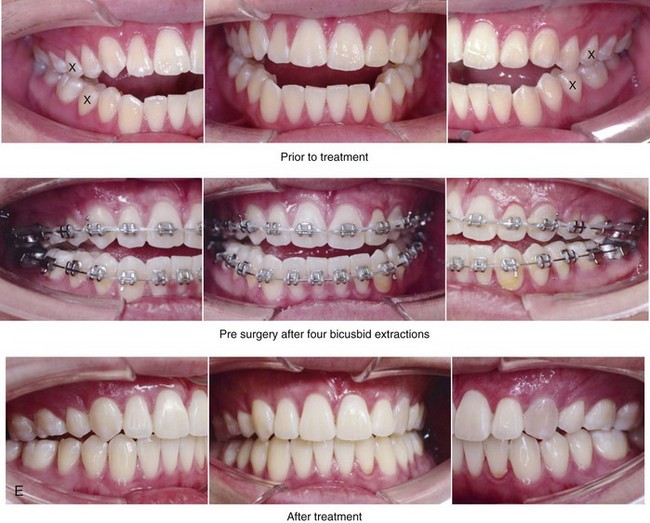

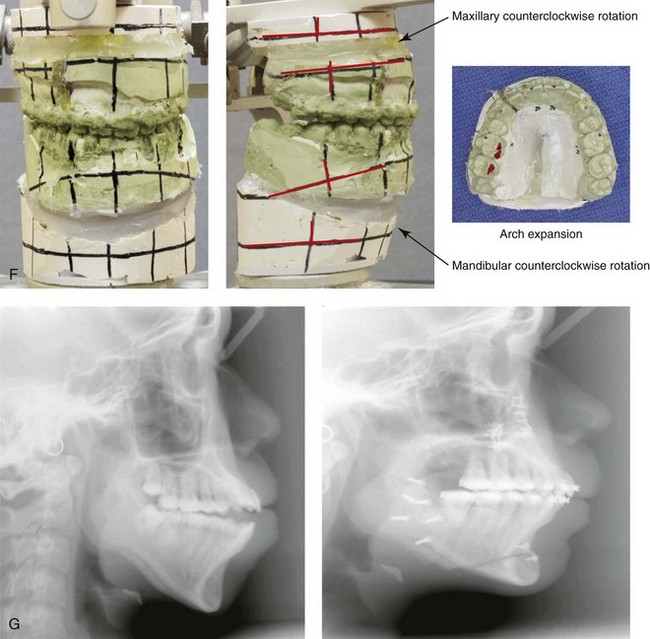

Figure 24-5 An 18-year-old Asian man was referred for surgical evaluation. He presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. Concerns included nasal obstruction, gingivitis, gummy smile, anterior open-bite malocclusion, lip incompetence, and retrusive profile. Orthodontic decompensation was carried out and included four bicuspid extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical shortening, minimal horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and transverse widening); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, before surgery with four bicuspid extractions, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Despite the bicuspid extractions, procumbency remains.

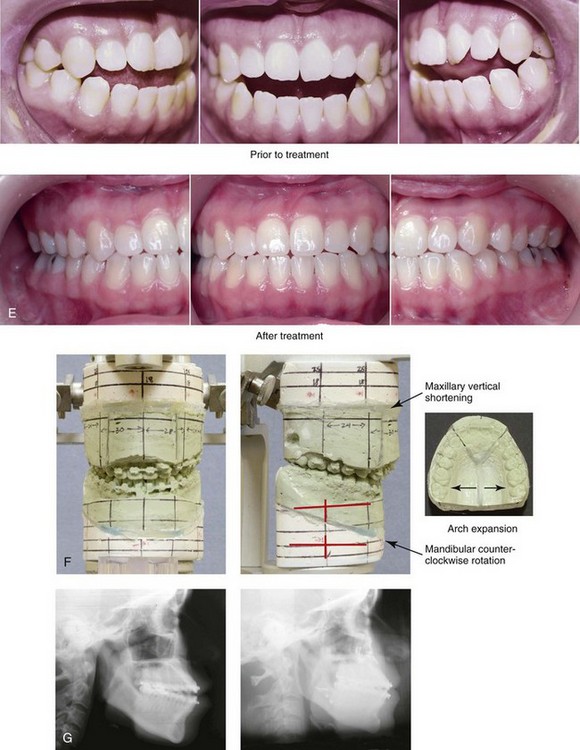

Figure 24-6 One of two 15-year-old twin girls who was referred for surgical evaluation. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. Orthodontic treatment was carried out without extractions, and maxillary incisor procumbency remained. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (minimal horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before orthodontics, before surgery, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that demonstrate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

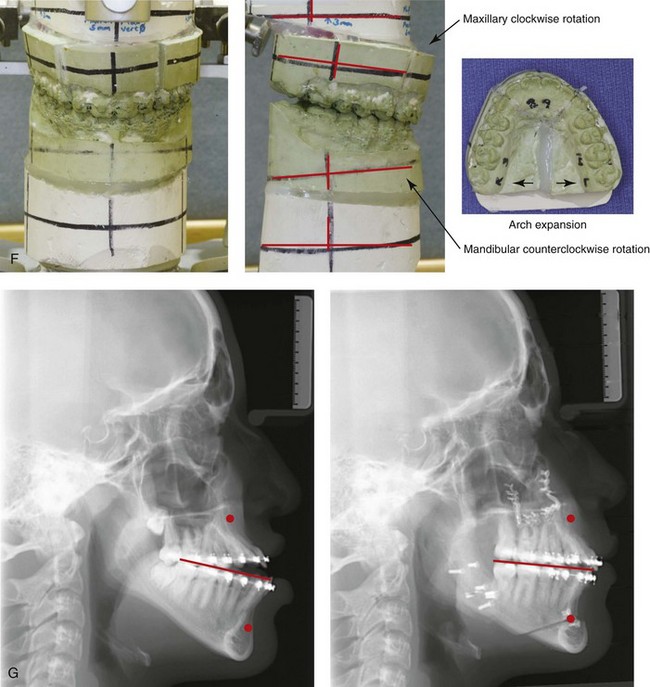

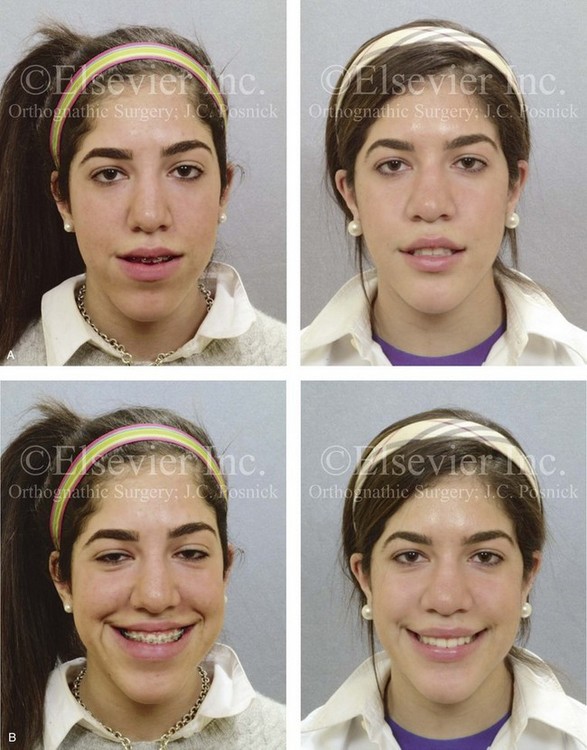

Figure 24-7 The 15-year-old twin sister of the patient shown in Figure 24-6 was also referred for surgical evaluation. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. She presented with a Class III anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical shortening, clockwise rotation, and arch expansion); sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before treatment, before surgery, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

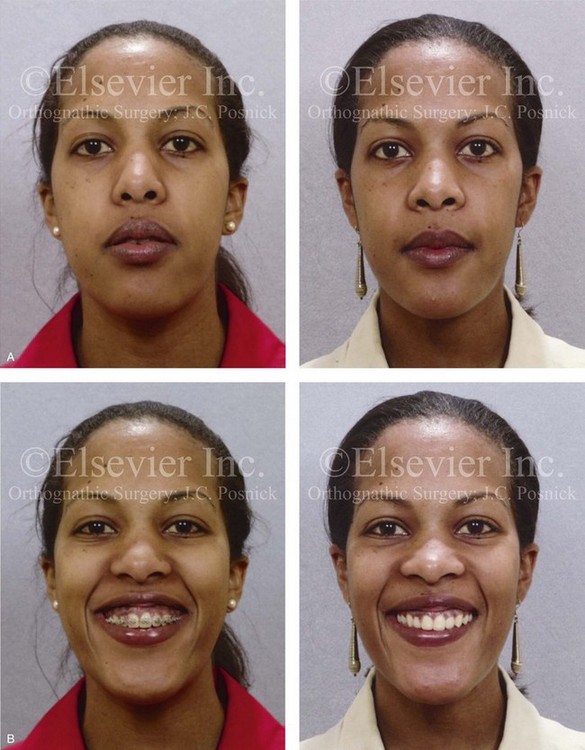

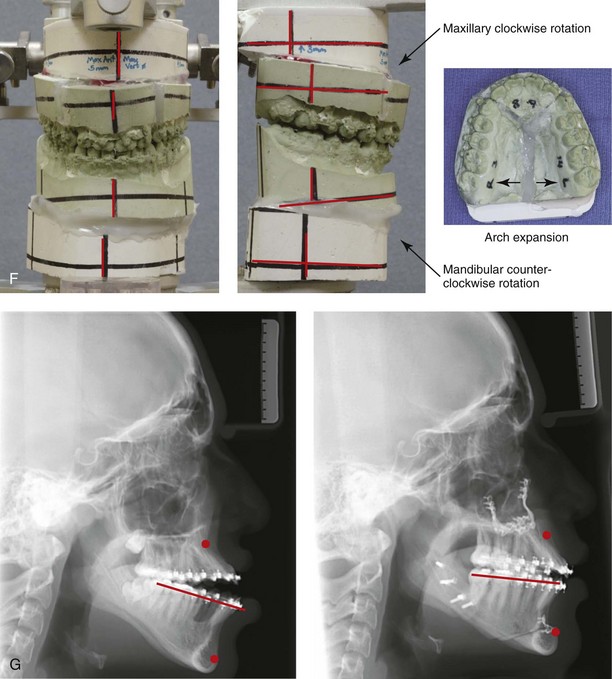

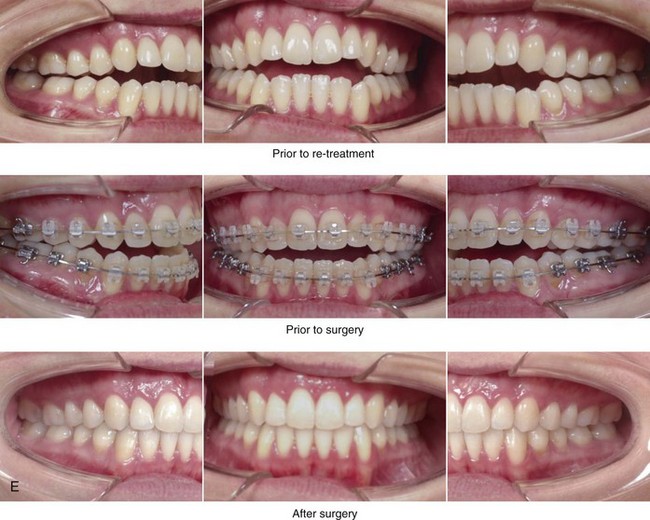

Figure 24-8 A 28-year-old woman arrived for the evaluation of malocclusion, lip incompetence, nasal obstruction, and anterior open bite malocclusion. She had previously undergone Phase I orthodontics that included rapid palatal expansion and an attempt at growth modification before graduating from high school. She now presented with a Class II anterior open-bite dental protrusive malocclusion. She underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach without extractions. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le For/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses