CHAPTER 22 MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH FACIAL DISFIGUREMENT

Patient Rehabilitation

Patient Rehabilitation

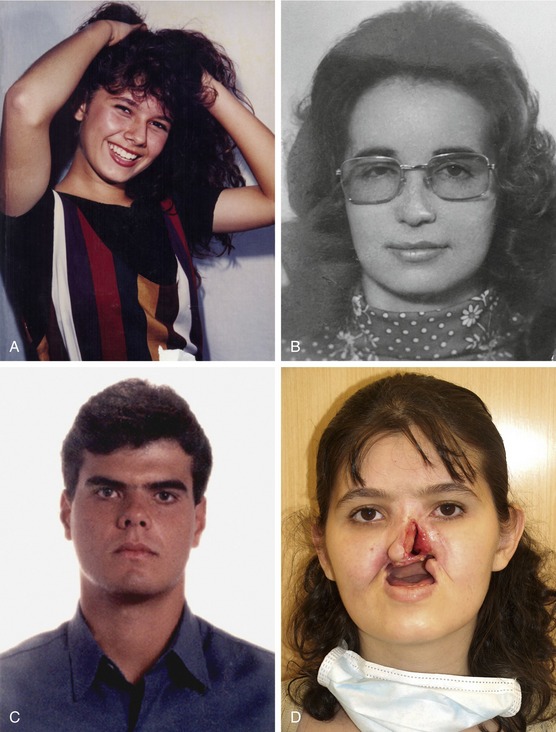

Patients with tumors in the head and neck region seek treatment because they hope to be free from the disease and go back to their ordinary lives. New medical approaches and treatment modalities can prolong the lives of patients with tumors of the head and neck region and, in some cases, control or even cure the disease. Unfortunately, the surgical removal of tumors in this area can cause severe facial disfigurement that, in a very short time, abducts the bearer of a facial deformity from social life. The people shown in Figure 22-1 had been enjoying life, but suddenly became incapable of doing so due to their disease and tumor resection.

Figure 22-1. A-C, Three patients prior to the onset of disease. D–F, Patients after tumor resection.

All of these points are necessary for the successful rehabilitation of disfigured patients. When they do not occur it is the patient who pays a high price in the end (Figure 22-2).

For the nonirradiated patient success rates of 94.4%, 96.3%, and 97% have been reported with the flange implant system (Nobel Pharma [Nobel Biocare, Yorba Linda, CA]).1–3 For the irradiated patient the success rate is somewhat lower and has been described between 57.9% and 64%; a later study confirmed these outcomes, reporting a success rate of 62%.4,5

Surgical intervention into irradiated bone may initiate osteoradionecrosis and, to minimize this risk, the possibility of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy is introduced. The standard protocol (modified Marx protocol)6 for this approach is described as 20 dives in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber (one dive per day, 2.4 ATA for 90 minutes) prior to the surgery, surgery at the 21st day, followed by another 10 dives (one per day) after the surgery.

Osseointegrated Implants

Osseointegrated Implants

From the macroscopic biomechanical point of view, a fixture is osseointegrated if there is no progressive relative motion between the fixture and the surrounding living bone and marrow under functional levels and types of loading for the entire life of the patient.7

Until 1977, when the osseointegration concept was applied to extraoral applications by Brånemark and colleagues,8,9 the most common means of retention for facial prosthesis were:

Unfortunately, these techniques have not proved to be retentive because the adhesive properties of the glue may be compromised by perspiration, sometimes causing embarrassing situations due to prosthesis displacement in public. Another disadvantage of adhesive retention is that daily application and removal of adhesives tends to deteriorate the margins of the prosthesis very quickly, reducing its durability and compromising the aesthetics (Figure 22-3). In addition, the skin bed that hosts the prosthesis might be compromised by radiotherapy, making tissue damage more probable.10–13

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses