CHAPTER 21. Melanoma and other pigmented lesions

Melanoma is a highly malignant oral tumour. It usually appears as a pigmented patch which must be distinguished from many other pigmentations listed in Box 21.1.

Box 21.1

Oral pigmented lesions

Usually brown or black

Typically purple or red

• Amelanotic melanomas

• Erythroplasia (Ch. 16)

• Haemangiomas (Ch. 20)

• Kaposi’s sarcoma (Ch. 20)

• Purpura (Ch. 26)

• Other blood blisters

• Telangiectases

• Lingual varices (Ch. 14)

• Pyogenic granuloma (Ch. 19)

• Pregnancy epulis (Ch. 19)

• Giant-cell epulis (Ch. 19)

• Geographical tongue (Ch. 14)

• Erythematous candidosis (Ch. 12)

• Median rhomboid glossitis (Ch. 14)

LOCALISED MUCOSAL PIGMENTATION → Summary p. 337

Physiological and racial pigmentation

This is the most common cause of oral pigmentation. The gingivae are particularly affected (Fig. 21.1). The inner aspect of the lips is typically spared. Intraoral pigmentation is commoner in those with a dark skin. However, light-skinned individuals have up to an average of 30 cutaneous local pigmented lesions of various types and occasionally one will be present in the mouth.

|

| Fig. 21.1

Racial pigmentation. The distribution of melanotic mucosa around the gingival margin is characteristic.

|

Post-inflammatory pigmentation

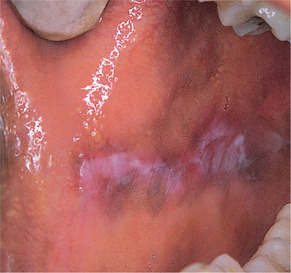

Inflammation interferes with the synthesis of melanin by melanocytes and its transfer to keratinocytes. Melanosomes escape from the epithelium into the underlying connective tissue where they are taken up by macrophages, a process known as melanin ‘drop out’. Accumulation of this subepithelial melanin gives rise to post-inflammatory pigmentation. The process is commoner in dark-skinned races. Intraorally, the most common inflammatory condition to become pigmented is lichen planus (Fig. 21.2) and it can become very dark. Pigmentation may also develop in other inflamed sites and scars. This type of pigmentation is also seen diffusely through the mouth of heavy cigarette smokers.

|

| Fig. 21.2

Pigmented lichen planus. Inflammatory conditions may become pigmented, especially in dark-skinned races. Here melanin delineates mucosa affected by lichen planus.

|

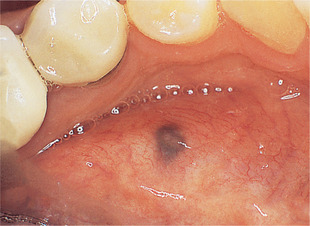

Amalgam tattoo → Summary p. 337

Fragments of amalgam frequently become embedded in the oral mucosa and form the most common pigmented patches which may simulate melanomas clinically. They are usually close to the dental arch and typically 5 mm or more across (Fig. 21.3). Dense tattoos may be radiopaque.

|

| Fig. 21.3

Amalgam tattoo. Typical appearance and site; however, the lower second premolar from which the amalgam probably originated has been crowned.

|

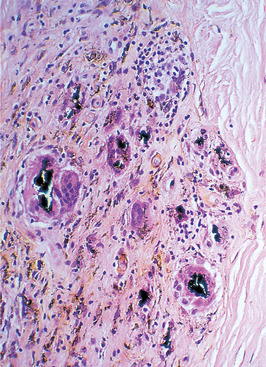

Pathology

Amalgam is seen as brown or black granules deposited particularly along collagen bundles and around small blood vessels (Fig. 21.4). There may be no inflammatory reaction or there may be a foreign body reaction with amalgam granules in the macrophages or giant cells.

|

| Fig. 21.4

Amalgam tattoo. There are large fragments of amalgam surrounded by foreign body giant cells and macrophages and smaller particles dispersed in fibrous tissue. Silver leaching from the smaller fragments has stained the adjacent collagen brown.

|

Excision is necessary to exclude a melanoma.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome → Summary p. 337

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, a rare heritable disease, is characterised by multiple mucocutaneous pigmented macules and intestinal polyposis. The pigmented macules typically develop during the first decade of life and can be widespread, affecting the hands and feet and perioral skin as well as the oral mucosa. Cutaneous macules usually fade after puberty but the oral macules persist (Fig. 21.5).

|

| Fig. 21.5

Peutz–Jehgers syndrome. There are multiple flat, pigmented patches on the palate. Those on the lips are most characteristic but fade with age.

|

Clinically, the oral macules resemble other melanotic macules and affect the lips, buccal mucosa, tongue and palate.

The intestinal polyps mainly affect the small intestine, are regarded as hamartomatous and rarely undergo malignant change. Colon cancer is a hazard but the risk for breast and gynecological cancers is particularly high. Multiple oral melanotic macules may therefore indicate the need for cancer screening.

Histologically, the oral macules show slight acanthosis and melanin in the basal layer. The melanocytes may have elongated dendritic processes.

The genetic locus of this syndrome is the mutated gene LKB1(STK11) on chromosome 19p. This was the first gene to be found that predisposes to cancer by disabling protein kinase activity.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses