Chapter 20

Rheumatologic and Connective Tissue Disorders

Rheumatologic (or rheumatoid) disease is much more than “arthritis” and encompasses a large group of disorders of the rheumatic diseases that affect bones, joints, and muscles.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Rheumatologic (or rheumatoid) diseases have significant personal and economic impact. According to the Arthritis Foundation, more than 40 million Americans suffer from various forms of arthritis, and more than 8 million of them are disabled. In terms of its overall economic impact, arthritis costs the American economy more than $20 billion annually, and nearly 30 million workdays are lost per year.

Categories of Musculoskeletal Diseases

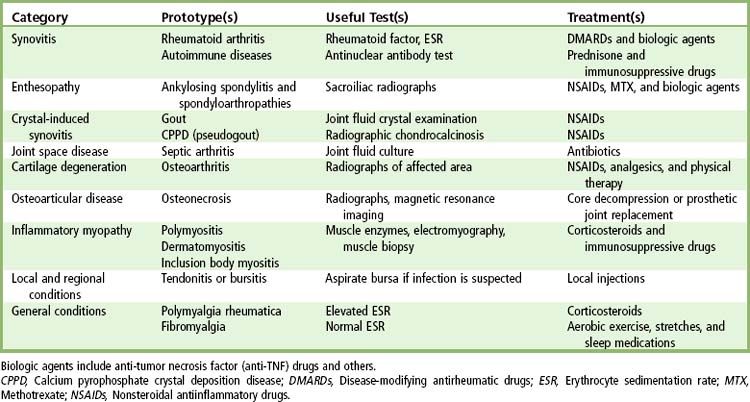

Musculoskeletal diseases can be classified into nine categories, defined by the predominantly affected tissues, such as joint, synovium, cartilage, or connective tissues (

Anatomy

The structures that are commonly involved in rheumatoid diseases include the joint, the joint cavity, synovial fluid, and periarticular structures. The lining membrane, known as the synovium, consists of a thin layer of macrophages (type A cells) and fibroblasts (type B cells) with a sublining of rich, vascular, loose connective tissue. Hyaline cartilage overlies the bony end plates and provides a cushion to joint motion. The cartilage has high water content and obtains its nutrition solely from the synovial fluid, which is derived from the synovium primarily as an ultrafiltrate of plasma. The synovium also secretes specialized molecules into the synovial fluid, such as hyaluronic acid. An intact bony end plate is required to support the cartilage. The joint capsule and ligaments provide further support and blend with the periosteum. Periarticular anatomy is equally important and includes the tendons, bursae, and muscles associated with each joint.

Pathophysiology

The cause of musculoskeletal problems is usually inflammatory, metabolic, degenerative, tumor, or some combination thereof. Synovial inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, begin in the synovium and secondarily damage the cartilage, joint capsule, and bone. Inflammation at entheses, the insertion sites of tendons or ligaments on bone, is characteristic of the spondyloarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylitis. Crystal deposition disorders, such as gout or pseudogout, may also cause articular inflammation. Infections primarily involve the joint cavity (septic arthritis) or bone (osteomyelitis). The noninflammatory, degenerative disease osteoarthritis begins in the cartilage and leads to cartilage loss, subchondral new bone formation, and marginal bony overgrowth. Cartilage loss also may occur secondarily to synovial inflammation or trauma.

Although the rheumatologic diseases comprise a group of more than 100 important diseases, this chapter is limited to a discussion of eight: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Lyme disease, fibromyalgia (FMS), temporal arteritis, and Sjögren syndrome (SS), which are among the most common forms encountered, are more dentally related conditions, and can serve as models for the dental management of other forms. Several important items regarding the dental management of patients with rheumatologic and connective tissue disorders, including effects on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), salivary glands, and oral mucosal tissues, organ and system involvement, and drug therapy, are discussed here.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Definition

Incidence and Prevalence

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease of unknown origin that is characterized by symmetric inflammation of joints, especially of the hands, feet, and knees. Severity of the disease varies widely from patient to patient and from time to time within the same patient. Prevalence is somewhat difficult to determine because of lack of well-defined markers of the disease; however, estimates range from 1% to 2% of the population. Disease onset usually occurs between ages 35 and 50 years. RA is more prevalent in women than in men by a 3 : 1 ratio.

Etiology

The cause of RA is unknown; however, evidence seems to implicate an interrelationship of infectious agents, genetics, and autoimmunity. One theory suggests that a viral agent alters the immune system in a genetically predisposed person, leading to destruction of synovial tissues. Although the disease can occur within families, suggesting a genetic component, one specific causative gene has not been identified.

Pathophysiology and Complications

With RA, the fundamental abnormality involves microvascular endothelial cell activation and injury.

FIGURE 20-1 The joint surface (top) has lost its cartilage and consists of granulation tissue with scar tissue. Subchondral bone shows degenerative changes and areas of necrosis.

(Courtesy A. Golden, Lexington, Kentucky.)

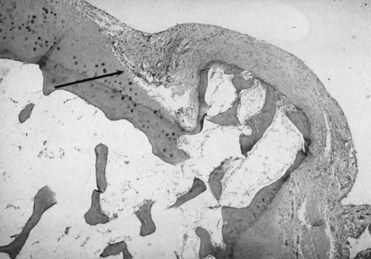

FIGURE 20-2 A micrograph of a pannus resulting from severe synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis. The pannus is eroding articular cartilage and bone (arrow).

(Courtesy Richard Estensen, MD, Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

A likely sequence of events begins with a synovitis that stimulates immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies. These antibodies form antigenic aggregates in the joint space, leading to the production of rheumatoid factor (autoantibodies). Rheumatoid factor then complexes with IgG complement, a process that produces an inflammatory reaction that injures the joint space.

An associated finding in 20% of patients with RA is the presence of subcutaneous nodules, which are commonly found around the elbow and finger joints. These nodules are thought to arise from the same antigen-antibody complex that is found in the joint. Vasculitis confined to small- and medium-sized vessels also may occur and probably is caused by the same complex.

RA is a pleomorphic disease with variable expression. The most progressive period of the disease occurs during the earlier years; thereafter, it slows. Onset is gradual in more than 50% of patients, and as many as 20% follow a monocyclic course that abates within 2 years. Another 10% experience relentless crippling that leads to nearly complete disability. The remainder follows a polycyclic or progressive course.

The life expectancy of persons with severe RA is shortened by 10 to 15 years. This increased mortality rate usually is attributed to infection, pulmonary and renal disease, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Many complications may accompany RA. Included among these are digital gangrene, skin ulcers, muscle atrophy, keratoconjunctivitis sicca (Sjögren syndrome), TMJ involvement, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, pericarditis, amyloidosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and splenomegaly (Felty syndrome).

Clinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

The usual onset of RA is gradual and subtle (

TABLE 20-2 Comparison of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Osteoarthritis |

|---|---|

| Multiple symmetric joint involvement | Usually one or two joints (or groups) involved |

| Significant joint inflammation | Joint pain usually without inflammation |

| Morning joint stiffness lasting longer than 1 hour | Morning joint stiffness lasting less than 15 minutes |

| Symmetric, spindle-shaped swelling of proximal interphalangeal joints and volar subluxation of metacarpophalangeal joints and Bouchard’s nodes of proximal interphalangeal joints | Heberden’s nodes of distal interphalangeal joints |

| Systemic manifestations (fatigue, weakness, malaise) | No systemic involvement |

FIGURE 20-3 Hands of a patient with advanced rheumatoid arthritis.

(From Damjanov I: Pathology for the health professions, ed 4, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

Extraarticular manifestations include rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis, skin ulcers, Sjögren syndrome, interstitial lung disease, pericarditis, cervical spine instability, entrapment neuropathies, and ischemic neuropathies.

Box 20-1

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Adapted from Arnett FC, et al: The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised citeria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis Rheum 31:315-324, 1988.

Laboratory Findings

No laboratory tests are pathognomonic or diagnostic of RA, although they are used in conjunction with clinical findings to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory findings most commonly seen in RA include an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), the presence of C-reactive protein (CRP), a positive result on rheumatoid factor assay in 85% of affected patients, and a hypochromic microcytic anemia. In patients with Felty syndrome (RA with splenomegaly), a marked neutropenia may be present.

Antibodies to cyclic citrullinated proteins (CCPs) are autoantibodies, which are important in the diagnosis of RA.

Diagnosis

The American College of Rheumatology has established criteria for the diagnosis of RA (see

By definition, the diagnosis of RA cannot be made until the disease has been present for at least several weeks. Many extraarticular features of RA, the characteristic symmetry of inflammation, and the typical serologic findings may not be evident during the first month or two after disease onset. Therefore, the diagnosis of RA usually is presumptive early in its course.

Although extraarticular manifestations may dominate in some patients, documentation of an inflammatory synovitis is essential for a diagnosis. Inflammatory synovitis can be documented by demonstration of synovial fluid leukocytosis, defined as white blood cell (WBC) counts greater than 2000/µL, histologic evidence of synovitis, or radiographic evidence of characteristic erosions.

Medical Management

The treatment approach to RA is, by necessity, palliative because no cure as yet exists for the disease. The ultimate aim of management is to achieve disease remission for the patient. Remission is elusive, however, so more practical treatment goals are to reduce joint inflammation and swelling, relieve pain and stiffness, and facilitate and encourage normal function.

When an understanding of the determinants of disease outcome is acquired, a treatment strategy that will be useful and acceptable to the individual patient can be devised. These determinants include presence of rheumatoid factor, early onset of severe synovitis with functional limitation, joint erosions, persistent elevation of ESR or CRP, presence of extraarticular manifestations, and a family history of severe RA.

The major goals of therapy are to relieve pain, swelling, and fatigue; improve joint function; stop joint damage; and prevent disability and disease-related morbidity. These goals are constant throughout the disease course, although emphasis may shift to address specific patient needs. For example, some patients with advanced joint damage experience minimal swelling or constitutional symptoms and benefit most from physical therapy, joint reconstruction, and pain control. Most patients, however, require continued efforts to control the inflammatory process through disease-modifying therapy.

Drugs for the management of RA have been traditionally, but imperfectly, divided into two groups: those used primarily for the control of joint pain and swelling, and those intended to limit joint damage and improve long-term outcome (

TABLE 20-3 Drugs Used in the Management of Rheumatoid Disorders and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Drug(s) (Trade Name) | Dental and Oral Considerations |

|---|---|

| Salicylates | |

| Aspirin, Ascriptin, Bufferin, Anacin, Ecotrin, Empirin | Prolonged bleeding but not usually clinically significant |

| Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) | |

| Ibuprofen (Motrin), fenoprofen (Nalfon), indomethacin (Indocin), naproxen (Naprosyn), meclofenamate (Meclomen), piroxicam (Feldene), sulindac (Sulindac), tolmetin (Tolectin), diclofenac (Voltaren), flurbiprofen (Ansaid), diflunisal (Dolobid), etodolac (Lodine), nabumetone (Relafen), oxaprozin, ketorolac | Prolonged bleeding but not usually clinically significant; oral ulceration, stomatitis |

| Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 Inhibitors | |

| Celecoxib Rofecoxib |

None |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitors | |

| Etanercept Infliximab |

None |

| Injectable Glucocorticoids | |

| Triamcinolone hexacetonide | Adrenal suppression, masking of oral infection, impaired healing |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | |

| Prednisolone tebutate | |

| Methylprednisolone acetate | |

| Dexamethasone acetate | |

| Hydrocortisone acetate | |

| Triamcinolone diacetate | |

| Betamethasone sodium phosphate and acetate | |

| Dexamethasone sodium phosphate | |

| Prednisolone sodium phosphate | |

| Systemic Glucocorticoids | |

| Hydrocortisone, cortisone, prednisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone (Deltasone, Meticorten, Orasone, Articulose-50, Delta-Cortef, Medrol) | Adrenal suppression, masking of oral infection, impaired healing |

| Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) | |

| Antimalarial Agents | |

| Hydroxychloroquine, quinine, chloroquine (Plaquenil) | None |

| Penicillamine | |

| Cuprimine, Depen | None |

| Gold Compounds | |

| Gold sodium thiomalate (Auranofin), aurothioglucose (Myochrysine Ridaura, Solganal) | Increased infections, delayed healing, prolonged bleeding, oral ulcerations |

| Aralen | Increased infections, delayed healing, prolonged bleeding, glossitis, stomatitis |

| Sulfasalazine | |

| Azulfidine | Increased infections, delayed healing, prolonged bleeding, intraoral pigmentation |

| Immunosuppressives | |

| Azathioprine, cyclophosphamide | Increased infections, delayed healing, prolonged bleeding |

| Methotrexate, cyclosporine, chlorambucil (Imuran, Cytoxan, Rheumatrex) | Increased infections, delayed healing, prolonged bleeding, stomatitis |

NSAIDs, especially aspirin, constitute the cornerstone of treatment. Aspirin may be prescribed in large doses on an individual basis. A common approach is to start a patient on three 5-grain tablets four times a day, then to adjust the dosage on the basis of patient response. The most common sign of aspirin toxicity is tinnitus. Should this occur, dosage is decreased. In addition to aspirin, many NSAIDs are available for use (see

All NSAIDs can cause a qualitative platelet defect that may result in prolonged bleeding, especially when given in high doses. The effects of aspirin are irreversible for the life of the platelet (10 to 12 days); thus, this effect continues until new platelets have replaced the old. The effect of the other NSAIDs on platelets is reversible and lasts only as long as the drug is present in the plasma (see

In addition to NSAIDs, a variety of other drugs can be used to treat patients with RA (see

DMARDs, which commonly are employed in the treatment of patients with RA, are classified in various groups, each of which consists of multiple drugs (e.g., antimalarial agents, penicillamine, gold compounds) (see

Gold compounds may be effective in decreasing inflammation and retarding the progress of the disease, but the incidence of associated toxicity is high, and dermatitis with mucosal ulceration, proteinuria, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia may result. Antimalarial drugs (e.g., chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) are also used to treat patients with RA; they are usually given in combination with aspirin or corticosteroids.

In cases of refractory disease, immunosuppressive therapy has been used successfully and may include methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or azathioprine. These drugs may produce significant adverse effects, including severe oral ulceration. Methotrexate also may cause hepatic toxicity. COX-2 inhibitors and TNF-α inhibitors have recently proved effective in relieving the symptoms of RA (see

A group of drugs have been developed, labeled “biologic,” because they consist of monoclonal antibodies and soluble receptors that specifically modify the disease process by blocking key protein messenger molecules (such as cytokines) or cells (such as B lymphocytes). The development of biologic drugs has been based on an increasing understanding of the disease process. The key drivers of RA include cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin 1 (IL-1), and interleukin 6 (IL-6). An IL-1 receptor antagonist called anakinra had been appraised by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and rejected for use in the National Health Service as not being cost-effective.

The newer biologic agents etanercept and infliximab (and other TNF-α inhibitors) have been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis relative to the “gold standard” agent, methotrexate.

Combination Therapies

In people with moderate to severe disease activity, methotrexate often is used in combination with other agents.

Clinical tools for monitoring the patient’s well-being and the efficacy of therapy include self-assessment of the duration of morning stiffness and severity of fatigue, as well as functional, social, emotional, and pain status, as measured by a health assessment questionnaire. A patient-derived global assessment based on a visual analog scale is a simple and effective means of recording patient well-being. The number of tender and swollen joints is a useful measure of disease activity, as is the presence of anemia, thrombocytosis, and elevated ESR or CRP. Serial radiographs of target joints, including the hands, are useful in assessing disease progression.

Patient education is essential early in the disease course and on an ongoing basis. Patients are best served by a multidisciplinary approach with early referral to a rheumatologist and other specially trained medical personnel, including nurses, counselors, and occupational and physical therapists who are skilled and knowledgeable about RA. Appropriate medical care of patients with RA encompasses attention to smoking cessation, immunizations, prompt treatment of infections, and management of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and osteoporosis.

Dental Management

Medical Considerations

Because patients may have multiple joint involvement with varied degrees of pain and immobility, dental appointments should be kept as short as possible, and the patient should be allowed to make frequent position changes as needed (

Box 20-2 Dental Management

Considerations in Patients with Rheumatoid Disorders

Patient Evaluation/Risk Assessment (see

Potential Issues/Factors of Concern

| A | |

| Analgesics | If patient is taking aspirin or another NSAID or acetaminophen, be aware of dosing and the possibility that pain may be refractory to some analgesics; dosing and/or analgesic choices may need to be modified in consultation with the physician. |

| Antibiotics | Provide antibiotic prophylaxis in accordance with ADA (2003) guidelines ( |

| Anesthesia | No issues. |

| Anxiety | No issues. |

| Allergy | Allergic reactions or lichenoid reactions are possible in patients taking many medications. |

| B | |

| Bleeding | Excessive bleeding may occur if major surgery performed on patients who take aspirin or other NSAIDs. Bleeding usually is not clinically significant and can be controlled with local hemostatic measures. |

| Blood pressure | No issues. |

| C | |

| Chair position | Ensure comfortable chair position. Consider shorter appointments and use supports as needed (e.g., pillows, towels). |

| D | |

| Devices | Patients who have a prosthetic joint replacement should be managed according to ADA (2003) guidelines ( |

| Drugs | Obtain blood cell count with differential if surgery is planned for patients taking gold salts, penicillamine, antimalarials, or immunosuppressives. If patient is taking corticosteroids—secondary adrenal suppression is possible (see |

| E | |

| Equipment | No issues. |

| Emergencies | If surgery is performed, supplemental techniques may be necessary to control bleeding. |

| F | |

| Follow-up | Routine follow-up evaluation is appropriate. |

ADA, American Dental Association; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

The most significant complications associated with RA are drug-related (see

Patients who are taking gold salts, penicillamine, sulfasalazine, or immunosuppressive agents are susceptible to bone marrow suppression, which can result in anemia, agranulocytosis, and thrombocytopenia. As a rule, these patients should be followed closely by their physician for detection of this problem. If a patient has not undergone recent laboratory testing, a complete blood cell count with a differential white blood cell count should be ordered. Abnormal results should be discussed with the physician. If corticosteroids are used for prolonged periods, the potential for adrenal suppression exists. Management of this problem is discussed in

Prosthetic Joints

A potential long-term complication of chronic rheumatoid arthritis (also osteoarthritis

Although reports in the literature weakly associate PJI with dentally induced bacteremia, authors have questioned the validity of these reports. It appears that wound contamination or skin infection is the source of the vast majority of infections.

Unfortunately, however, many orthopedic surgeons have persisted in requesting that patients continue to receive antibiotic prophylaxis for all dental procedures.

In an effort to clarify the issue, in 1997 and updated in 2003, an advisory statement made jointly by the American Dental Association (ADA) and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) was published.

Box 20-3 High-Risk Patients with Prosthetic Joints

A more appropriate interpretation is that these patients are at increased risk for LPJI from the usual sources such as wound contamination and acute infection from distant sites. The advisory statement also is clear that the final decision on whether to provide antibiotic prophylaxis lies with the dentist, who must weigh perceived potential benefits against risks. The advisory statement provides suggested antibiotic regimens, should the practitioner elect to provide antibiotic prophylaxis (see

Box 20-4 Suggested Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimens

In 2009 the AAOS published an information statement that added a great deal of confusion to the dental management of patients with joint replacements. Antibiotic prophylaxis was suggested for all patients with joint replacements for dental procedures that produced bacteremia. This statement was made without input from the ADA and appeared to negate the 2003 advisory statement of the ADA and AAOS.

In 2010 the American Academy of Oral Medicine (AAOM) published a position paper in the Journal of the American Dental Association (JADA).

2 Base clinical decisions on the 2003 ADA/AAOS consensus statement

3 Consultation with the patient’s orthopedic surgeon to recommend following the 2003 guidelines until a new joint consensus statement is approved. If the orthopedist elects to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for a patient who would not receive it on the basis of the 2003 guidelines, the orthopedist can write the prescription for the desired antibiotic.

In November 2010 the ADA, AAOS, and IDSA began a series of meetings with the goal of developing an evidence-based recommendation for the dental management of patients with joint replacements. The process was estimated to take about 1 year. Until this recommendation is available, then, the dentist should consider one of the options suggested in the AAOM position paper.

A study that should have a great influence on the future recommendations of the ADA, AAOS, and IDSA was reported from the Mayo Clinic. The investigators concluded that dental procedure bacteremias were not associated with the onset of LPJIs and that antibiotic prophylaxis did not prevent PJIs.

Treatment Planning Modifications

Treatment planning modifications are dictated by the patient’s physical disabilities. A patient with marked systemic disability or limited or painful jaw function due to TMJ involvement should not be subjected to prolonged or extensive treatment, such as complicated crown and bridge procedures. If replacement of missing teeth is desired, consideration should be given to fabrication of a removable prosthesis because of the decreased chair time needed for mouth preparation and the ease of cleaning of the appliance. If a fixed prosthesis is desired, the realistic potential to keep it clean must be a significant factor in design. Unpredictable, progressive, or abrupt changes in occlusion are possible because of erosion of the condylar head. Therefore, the dentist and the patient should take these potential occlusal changes into consi/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses