Community Oral Health Planning and Practice

Basic Concepts

A Health—community health practice requires a broad view of health: “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity; a state characterized by anatomic, physiologic, and psychological integrity; ability to perform personally valued family, work, and community roles; ability to deal with physical, biologic, psychological, and social stress; freedom from the risk of disease and untimely death; the extent to which an individual or a group is able to realize aspirations and satisfy needs and to change or cope with the environment; a positive concept, emphasizing social and personal resources as well as physical capabilities”;1 a state of health may be described as a state of physical and mental well-being that facilitates the achievement of individual and societal goals

B Oral health—status of the oral cavity, encompassing all features, normal and abnormal, of the oral, dental, and craniofacial complex

C Determinants of health—consist of social and economic factors, the physical environment, and the person’s individual characteristics and behaviors; many determinants are nonmodifiable; risk factors are modifiable determinants; the study of public health focuses on attempts to modify risk factors through education and preventive therapies and to control other determinants through policy and changes to the structure of health care delivery2

D Public health—”the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical and mental health and efficiency through organized community efforts”;3 the combination of sciences, skills, and beliefs directed at the maintenance and improvement of the health of all persons through collective or social actions; characteristics include a teamwork approach, preventing rather than curing disease, dealing with population-level health rather than individual-level health, social responsibility for oral health, use of epidemiology and a multi-factorial approach to controlling and preventing disease, and application of biostatistics

1. Aggregate health of a group, community, state, nation, or group of nations

E Dental public health—“science and art of preventing and controlling oral diseases and promoting oral health through organized community efforts; that form of dental practice that serves the community as a client rather than the individual; concerned with the oral health education of the public, with applied dental research, and with the administration of group oral health care programs, as well as the prevention and control of oral diseases on a community basis”;4 the application of public health and all its characteristics to oral health

F Community—any group with common traits, shared features, or communal experiences; not strictly defined by traditional geographic boundaries; as broad as a region of a state or as focused as a nursing home community, including administrators, staff, residents, and caregivers

G Community health—generally synonymous with public health; full range of health services, environmental and personal, including major activities such as health education of the public and the social context of life as it affects the community; efforts that are organized to promote and restore the health and quality of life of the people; uses a population-based approach for identifying and addressing community-based problems

H Community oral health—services directed toward developing, reinforcing, and enhancing the oral health status of people, either as individuals or as groups and communities

I Access—an individual’s or group’s ability to obtain appropriate health care services

J Prevention—primary focus of community oral health is prevention; the wellness model focuses educational and behavioral efforts and programs toward prevention of disease and maintenance of an optimum state of well-being; three levels of prevention:

1. Primary—prevention of disease before it occurs

2. Secondary—early disease control, including early identification and prompt treatment

3. Tertiary—provision of services that prevent further disability

K Comparison of private health versus community health—steps are presented in Table 20-1; the focus of public health is to function as an interdisciplinary health team rather than as an individual practitioner to serve people in community settings, rather than the individual in private offices; a public health practitioner needs knowledge and skills in public health administration, research and epidemiological methods, prevention and control of oral diseases, provision and financing of oral health care, the availability of resources, and the adaptation of care and programs to diverse people from a variety of cultures

TABLE 20-1

Comparison of Private Dental Practice and Community Oral Health Practice*

| Private Dental Practice | Community Oral Health Practice |

| Assessment of client’s dental, health, pharmacologic, and sociocultural history and oral health status | Survey of community oral health status; situation analysis including assessment of population demographics, culture, mobility, economic resources, and infrastructure |

| Diagnosis of client’s oral health needs | Analysis of survey data to determine the oral health needs of the population |

| Treatment plan based on diagnosis, professional judgment, client’s needs, and priorities | Program plan based on data analysis, community priorities, and resources available |

| Treatment plan initiated; primary dentist may coordinate treatment with other providers (e.g., dental hygienists, specialists) | Program operation implemented; the group will comprise varied, sometimes interdisciplinary, personnel |

| Payment methods determined | Financing takes place throughout process; may be combination of local, state, and federal funds, philanthropic or community agencies |

| Evaluation during treatment, at specific intervals, on completion of treatment, or at all these times | Evaluation and appraisal is ongoing and varied, conducted in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, appropriateness, and adequacy |

*Education occurs at all levels to facilitate anticipated outcomes.

L Criteria for the traditional approach to a public health problem

1. A disease or other threat to health is widespread

2. The disease is one that can be prevented, alleviated, or cured

M Current approach to the criteria of a public health problem

1. Condition, practice, or situation that is widespread and an actual or potential cause of morbidity (disease) or mortality (death)

2. Public, nongovernmental agency (NGO), government, or public health personnel perceive that the condition is a public health problem

N Public health solution—solutions to public health problems that are directed to the community at large; possess seven characteristics:

1. Safe; not hazardous to life or function

2. Effective in reducing or preventing a targeted disease, condition, or practice

3. Easily and efficiently implemented

4. Potency maintained for a substantial time period

5. Attainable regardless of socioeconomic status (SES), education, or income

6. Effective immediately on application

7. Affordable; cost effective and within the means of a community

O Core functions of public health—nationally identified; form the foundation of all community health activities5

1. Assessment—regular and systematic collection, assembling, and analysis of data related to the health of the population and making the data available for use by various agencies

2. Policy development—development of comprehensive public health policies based on scientific evidence

3. Assurance—provision of services necessary to achieve agreed-upon health goals related to improving the health of the public

P Levels of public health—each level provides various services and meets different needs of the population; various levels support the activities of other levels, but one level is not directly controlled by another; programs at lower levels are often funded by grants from higher levels

1. Local—responsible for direct administration of educational, preventive care, and patient care programs

2. State—consultation to the local level and other agencies; channels federal and state funds such as Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP); conducts programs in rural areas that do not have local public health agencies

3. National—numerous national public health government agencies are involved in public health issues of national significance; some of the more significant ones that are a resource in community programming are:

a. NIH (National Institutes of Health)—conducts epidemiologic research, provides science transfer, and publishes and distributes educational materials; several are relevant to oral health, such as National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and National Institute on Aging (NIA)

b. CDC (Centers for Disease Control)—provides expertise, information, tools, and community collaboration to assist agencies with community programming; formulates recommendations for evidence-based practice (e.g., infection control and use of F varnish), develops educational programs (e.g., tobacco cessation) for local implementation, and provides surveillance data (e.g., fluoridation)

c. PHS (Public Health Service)—commissioned officer core led by the Surgeon General that staffs clinics (e.g., in federal prison programs and Indian Health Service programs) and responds to national crises

d. IHS (Indian Health Service)—provides direct patient care and community health programming for Native American populations

e. DOD (Department of Defense) and VA (Veteran’s Administration) provide direct care for specific populations

4. International—World Health Organization (WHO) is the best-known and largest international health agency; primarily serves developing countries but also monitors health conditions and establishes programs to coordinate health care throughout the world; also Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO)

Q National documents relevant to community oral health programming—classic documents continue to provide a basis to prioritize programs and target specific population groups;5 these documents complement each other as they categorize community oral health needs of the population and strategies to address those needs; are based on the three core public health functions:

1. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General6—the key points of the publication are:

a. Oral health is more than just healthy teeth

b. Oral health is integral to general health for all Americans

c. General health factors (e.g., tobacco use, poor diet, obesity, diabetes, etc.) affect oral and craniofacial health

d. Oral health can be achieved by all Americans

e. Currently, disparities exist in the oral health of Americans

2. A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health7—includes five principles and implementation strategies designed to result in programs that will more effectively contribute to the goal of optimum oral health for all Americans:

a. Change perceptions about oral health

b. Build the science, and accelerate the transfer of the science

c. Increase collaborations (partnerships, coalitions)

3. Healthy People 20208—a comprehensive list of disease prevention and health promotion objectives including developmental objectives that have no baseline data source (see Box 20-1 for detailed list of oral health and related objectives); establish priorities for community programming for the decade 2010 to 2020; similar to Healthy People 2010 objectives, with more topic areas, some objectives remaining the same, some revised, and some new ones and more realistic targets set9 based on progress made toward Healthy People 2010 objectives;10 oral health objectives are organized into six major categories:

R Roles of the dental hygienist reflect the various activities in public health11

1. Clinician—provides direct client care based on sound scientific information

2. Educator—uses valid educational theories to present scientific information to individuals and groups to prevent disease and promote oral health

3. Advocate—promotes change and advances the health of the public through legislation and public policy

4. Researcher—determines which procedure, products, and programs most effectively promote oral health and prevent disease, and communicates those findings

5. Administrator/manager—administers and manages programs aimed at promoting oral health

Epidemiology

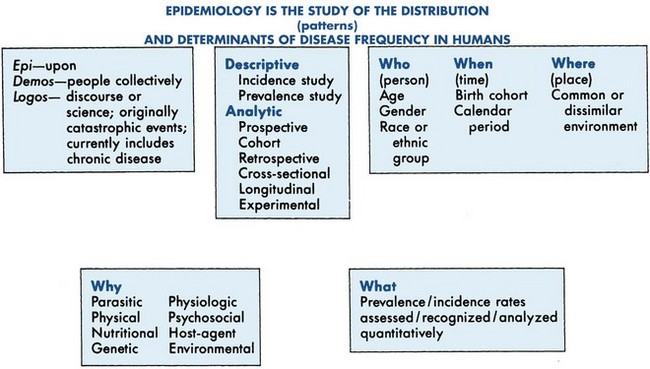

1. Epidemiology—study of health-related states in human populations and how these states are influenced by the environment and ways of living, including the nature, cause, control, and determinants of health and disease as well as related factors; concerned with factors and conditions that determine the occurrence and distribution of health, disease, defects, disability, and deaths among individuals and groups; characterized by the use of statistical and research methods to focus on comparisons between groups or defined populations (Figure 20-1)

FIGURE 20-1 The study of epidemiology.

2. Applied epidemiology—the application or practice of epidemiology to address public health issues

1. Study patterns among groups; establish a history of disease in a population

2. Collect data to describe normal biologic processes

3. Understand the natural history of disease

4. Test hypotheses for prevention and control of disease in populations

5. Plan and evaluate health care services

6. Study nondisease entities such as accidents, suicide, or injury

7. Measure the distribution of diseases in populations

8. Identify risk factors, risk indicators, risk markers, and other determinants of disease such as health literacy

9. Estimate risk of diseases among population groups

10. Evaluation of intervention and preventive strategies to control disease

11. Evaluate trends in chronic disease and social epidemiology

12. Identify syndromes and precursors

13. Evaluate the appropriateness and utility of health services

C Characteristics of epidemiology

1. Groups rather than individuals are studied

2. A multi-factorial approach is used to study disease (multiple causation); modifiable risk factors are controlled to control the disease or condition

3. Determinants—risk factors or events that are capable of bringing about a change in health; the various factors that make up the multi-factorial approach to a disease or health condition

4. Epidemiologic triad (epidemiologic triangle)—the traditional model of infection or disease causation that is used to study the occurrence and distribution of disease; includes an external agent (etiologic agent), a susceptible host, and an environment that brings the host and agent together so that disease occurs; it is the ongoing interaction among these factors that affects disease or health status:12

a. Host factors—intrinsic factors such as genetic makeup, immunity to disease or natural resistance, age, gender, race, ethnic background, physiologic state, gender, culture, level of immunity, physical or morphologic factors; fitness, personal lifestyle and habits, attitudes, and behaviors that influence an individual’s exposure; dietary excesses and nutritional deficiency, susceptibility, response to an agent or environmental factor

b. Agent factors—chemical, microbial, physical or mechanical irritants; parasitic, viral, or bacterial agent whose presence, excessive presence, or absence, in the case of immunodeficiency diseases, is essential for the occurrence of disease

c. Environment factors—extrinsic factors, such as climate or geography, culture, food and water sources, socioeconomic conditions, pollution and sanitation, animal hosts and vectors that provide an opportunity for exposure to disease

d. Time dimension—exposure to factors occurs over a period of time; the time required for the disease or condition to occur varies according to the other factors

5. Burden of disease—cumulative effect of a broad range of harmful disease consequences on a community, including the health, social, and economic costs to the individual and to society

6. Preventive intervention—strategies to eliminate risk factors and to reduce occurrence of disease

D Related epidemiology concepts

1. Acute disease—beginning abruptly with marked intensity or sharpness, and then subsiding after a relatively short period; often treatable

2. Chronic disease—developing slowly and persisting for a long period, often for the remainder of the lifetime of the individual

3. Cluster—an aggregate of cases of a disease, or other health-related conditions, particularly cancer or birth defects, closely grouped in time or space; the number of cases may or may not exceed the expected number; frequently, the expected number is not known

4. Endemic—continuing problem involving normal disease prevalence; the expected number of cases indigenous to a population or geographic area

5. Epidemic—a disease of significantly greater prevalence than normal; more than the expected number of cases; a disease that spreads rapidly through a demographic segment of a population

6. Pandemic—an epidemic that crosses international borders to affect a large proportion of the geographic population of a continent, people, or the world

7. Population at risk—includes persons in the same community or population group who can acquire a disease or condition

8. Mortality—death from a disease or condition

9. Morbidity—presence of disease; any departure, subjective (personal) or objective (clinically measurable), from a state of physiologic or psychological well-being

E Concepts related to measurement of disease and its distribution in epidemiology

1. Basic screening—a rapid assessment accomplished in a short time by visual detection and providing information about gross dental and oral lesions; can be accomplished with a tongue blade, dental mirror, and appropriate lighting

2. Epidemiologic examination—a detailed visual–tactile assessment accomplished with dental instruments and a light source in a survey; provides more detailed information than basic screening; differs from a clinical examination in that it does not involve a clinical diagnosis and resulting treatment plan

3. Surveillance—ongoing, constant, systematic observation, persistent watching over, scrutiny, analysis, and evaluation of health data to assess changes in populations related to disease, conditions, injuries, disabilities, or death trends, for the purpose of program planning; essential feature of epidemiology

4. National Oral Health Surveillance System (NOHSS)—a collaborative effort between the CDC Division of Oral Health and the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) to track oral health indicators on a state and national level using a variety of clinical and nonclinical methods, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES); nine oral health indicators are routinely assessed, based on the Healthy People objectives:

5. Monitoring—intermittent measurement to detect changes in the environment or in the health status of populations; less accurate than surveillance

6. Status—current state of a disease or health-related condition in the population

7. Trend—long-term changes or movements in disease patterns and health-related conditions in the population identified by examining surveillance data

8. Validity—the accuracy of a measure; produced by measuring what is supposed to be measured

9. Sensitivity—the ability of a test to accurately identify the presence of a disease or condition when the disease is, in fact, present

10. Specificity—the ability of a test to accurately identify the absence of a disease or condition

11. Predictive value—ability of a diagnostic test to accurately measure both the presence and absence of disease

12. Reversal—also called negative reversal; a change of diagnosis in an illogical direction over a period; a positive reversal is a change of the measurement made in error in a logical direction

13. Reliability—consistency or reproducibility of a measurement over time

14. Inter-examiner reliability—the agreement among two or more examiners as they apply an index or instrument to measure a disease or condition

15. Intra-examiner reliability—the consistency of a single examiner in the application of an index or instrument over time to measure a disease or condition

16. Calibration—the standardization of examiners to increase reliability as they apply epidemiologic measurements

17. Count—simplest measure of a disease or condition occurring in a population; the actual number of cases

18. Rate—the numeric expression of disease in a population in which the number of disease occurrences appears as the numerator and the number of possible occurrences (entire population) appears as the denominator; usually expressed as a standardized denominator such as 100 or 1000, and includes a time dimension, usually a year; allows for valid comparisons from year to year or population to population; for example, the number of deaths of newborn infants within the first year of life per 1000 births or the percentage of people diagnosed with oral cancer during a specific year

19. Incidence—the rate of new cases of a disease during or over a specific period; incidence is a rate

20. Prevalence—the numeric expression of the total number of all existing cases of a disease or health condition in a population measured at a given time, in relation to the number of individuals in the population; expressed as a proportion; can be expressed as a percentage; does not include a time dimension like incidence does

21. Occurrence—general term of frequency of disease that does not distinguish between incidence and prevalence

22. Ratio—expression of the magnitude of one occurrence of disease exposure in relation to another with a fraction; in contrast to a proportion, a relationship between the numerator and denominator, for example, ratio of dentists to hygienists, does not exist

23. Eradication—the elimination of the infectious disease agent through surveillance and containment; contrasted to control, which is to keep the disease at a minimum level so that it no longer poses a health problem

24. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)—routinely conducted national health surveys carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NCHS/CDC) to monitor the health and nutritional status of U.S. adults and children of all ages; conducted through interviewing and direct physical and dental examinations; began in the 1960s and has evolved to the current continuous program that has a changing focus on a variety of health and nutrition measurements to meet emerging needs; the survey examines a nationally representative sample of about 5000 persons each year, located in counties across the United States, 15 of which are visited each year; oral health is one of the areas of diseases and health indictors monitored by NHANES12

25. Socioeconomic status (SES)—includes education, income, occupation, attitudes, and values; frequently evaluated as it relates to distribution of disease and health-associated characteristics in the population

Epidemiology and Research

A Evidence-based practice13,14

1. Involves the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence to make decisions about the care of individual clients

2. Evidence alone is not sufficient to make decisions; the clinical expertise of the professional and client preferences and values are combined with the best available external clinical evidence from a body of rigorous research findings to make evidence-based practice decisions15

3. Evidence is ranked in the following order:16

a. Systematic reviews, preferably with meta-analysis; Cochrane reviews

b. Randomized controlled clinical trials

c. Nonrandomized controlled clinical trials

e. Case-control and cross sectional studies

f. Case series, case reports, other descriptive studies

g. Editorials, reports of expert committees, opinions of respected authorities

h. Studies that do not involve human participants (laboratory or animal model studies)

4. The gold standard of evidence (best clinical evidence available) is at least one published systematic review of multiple, well-designed randomized controlled trials

5. Evidence-informed practice relates to the practice of the dental hygienist in all roles and settings, not just clinical; has implications for all aspects of community oral health practice

6. All oral health care must be evidence informed; lifelong learning and access to quality research findings are critical to evidence-based practice

B Research—continual search for truth using the scientific method; systematic and objective inquiry through laboratory, field, and clinical investigations that lead to discovery or revision of knowledge, resulting in improvements in health and health care delivery

C Scientific method—methods used in any type of research that increase the likelihood that information gathered will be relevant, reliable, and unbiased; steps of the method include:

1. Identification and statement of the problem

2. Formulation of a hypothesis

3. Collection, organization, and analysis of data

5. Verification, rejection, or modification of the hypothesis

D Categories of community oral health research

1. Epidemiologic research to determine the presence and distribution of disease in the population and factors that relate to the occurrence of disease within the population

2. Clinical trials and tests of techniques and products to prevent and control disease

3. Research in educational techniques and the behavioral sciences related to oral health education

1. Risk identifies attributes that are associated with a disease (from case-control and cohort studies); causality identifies factors that have been demonstrated to be causally related (from randomized controlled clinical trials)

2. Risk is established with analytic studies; causality is established with experimental studies

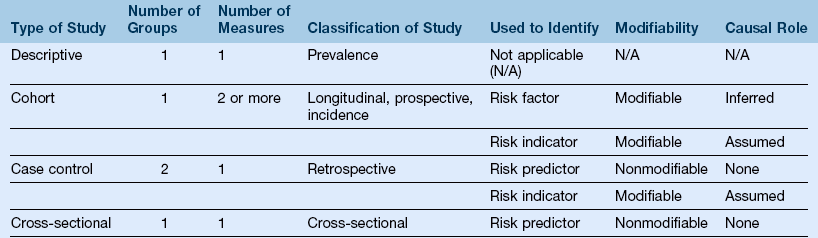

3. Types of risk attributes—different types are identified with different types of analytic studies (Table 20-2)

TABLE 20-2

Types of Non-experimental Studies and Risk

Data from CF Beatty: Oral epidemiology. In Nathe CN: Dental public health and research, ed 3, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2011, Pearson.

a. Risk factors—strong indication of risk, causality is inferred; can be modified; should be an important consideration in making recommendations to clients

b. Risk indicators—weaker indication of risk; causality may be incorrectly assumed; can be modified; should be applied with care when making recommendations

c. Risk predictor—also called risk marker or demographic risk factor; nonmodifiable; has no role in making recommendations to clients but has importance in identifying target populations for community oral health programs

F Three classifications of epidemiologic research:

1. Descriptive research—involves description, documentation, analysis, and interpretation of data to evaluate a current event or situation; does not test specific hypothesis but helps increase understanding of diseases; uses survey method with a cross-sectional design (Table 20-3)

TABLE 20-3

Comparison of Clinical Trials and Epidemiologic Surveys

| Clinical Trial | Epidemiologic Survey | |

| Populations | Experimental and control groups are specially constituted as representative samples from appropriate populations | Naturally occurring samples of target populations are usually studied |

| Sample size | Sample sizes are often small, particularly when “treatments” are more complicated | Fairly large sample sizes are used |

| Time frame | Trials are conducted over a period, usually varying from 1 week to 6 months to several years (e.g., dental caries research), depending on treatment involved and disease or condition measured, to compare treatment outcomes | Surveys are usually cross-sectional in design, using only one period; longitudinal designs are used occasionally |

| Methods | Although assessment methods may include indices, biomedical instruments, or physiologic measures, methods have validity, reliability, and clinical significance | Indices used for assessment and to establish the disease level of selected populations; these indices are, in general, used for comparison of data for different populations |

| Data | Data generated from clinical trials are applicable to specific hypothesis testing | Data generated from surveys are used to establish underlying etiologic factors and derive possible preventive methods, leading to the development of hypotheses to be tested by controlled clinical trials |

2. Analytic research—observation of a disease or condition to identify determinants of the disease by showing relationships or associations between diseases and other factors (risk factors or risk indicators); does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship; analytic studies are also called observational or development studies; noninterventional; types of analytic studies (see Table 20-2):

a. Cohort—a well-defined group (cohort means homogeneous group) is observed over time to determine the natural progression of a disease or condition after exposure without controlling any factors; the cohort can be compared with a homogeneous group not exposed to the disease; longitudinal; prospective; establishes incidence; used to confirm risk factors

b. Case-control—two groups are compared, one group with a disease or condition (called cases) and a second group without it (called controls), to identify factors in their history that can be associated with the disease or condition; retrospective; used to identify risk indicators and risk predictors but cannot be used to confirm risk factors; usually used to examine relationships among variables that cannot be studied prospectively because of ethical concerns about research participants

c. Cross-sectional—representative cross-section of the population (one group, but several subgroups) is observed at one point in time, and disease attributes and potential risk attributes are assessed at this same point in time to associate them with each other; used to identify risk indicators and risk predictors but cannot be used to confirm risk factors; used to identify prevalence

(1) Prospective—study planned before data are collected; observations made forward (into the future)

(2) Longitudinal—conducted over a long period to observe the progression of a disease or condition (length of time depends on condition being studied)

(3) Retrospective—study using data collected in the past; also termed ex-post facto or causal-comparative

3. Experimental research—a carefully designed study to test a hypothesis after analytic studies have inferred the cause of the disease; deliberate application or withholding of the supposed cause or controlling agent of a condition and observation of the result (longitudinal); used to determine the effectiveness of altering some factor or factors to establish cause-and-effect relationships (causality); a randomized clinical trial is a well-controlled experimental study with humans; an experimental study that is not well controlled is called quasi-experimental (see Table 20-3)

a. Requirements for an experimental study

(2) Control of extraneous variables

(3) Randomization (random assignment to groups)

(4) Control of errors in measurement to increase validity and reliability

(5) The independent variable is manipulated

(6) The dependent variable is measured

(7) The independent variable occurs before the dependent variable in design

b. A representative sample is required to allow for generalization (also called inference); replication studies (repeated studies with different samples) are frequently done to compensate for the poor generalizability (low external validity) resulting from the use of small convenience samples; multiple-site studies broaden the representation of the population and improve the generalizability of findings

(1) Pretest/post-test—the dependent variable is measured before and after introducing the independent variable; provides a baseline measure for comparison

(2) Post-test only—the dependent variable is measured only after introducing the independent variable; controls any possible effect of the pretest procedure on the dependent variable

(3) Split mouth—procedure unique to oral health research, in which each side of the mouth receives a different intervention; controls subject-related variables (variables that can vary from one participant to another)

(4) Cross-over—each group receives a different intervention or control and after a period, they are switched over to the opposite treatment, with an intervening washout period, during which no treatment is given, to eliminate the possibility of the first treatment affecting the second one; controls subject-related variables

(5) Time-series (repeated measures)—design in which the dependent variable is measured several times over a specific period, to determine whether its effect on the dependent variable holds over time

(6) Blind (or masking)—this refers to examiners measuring the dependent variable without knowing the group assignment, to eliminate bias; if both examiners and participants are unaware of their group assignments, it is called double-blind

(7) Designs can be combined; for example, a study can combine double-blind, pretest/post-test, split mouth, and repeated measures designs to test the effectiveness of an antimicrobial to reduce or control periodontal pocket depths over a long period

G Hypothesis—a predictive statement of the expected outcome or relationship among variables; answers the research question in a manner that is observable and measurable

1. Null hypothesis—negative statement of the hypothesis that assumes the absence of statistically significant differences between the sample groups, for example, statement that no difference exists in the effectiveness of the two treatments; this is the hypothesis that is statistically tested

2. Research hypothesis—also called the positive or alternative hypothesis; positive statement of the hypothesis is in terms that express the opinion or prediction of the researcher, for example, statement that a difference exists in the effectiveness of the two treatments

H Variables—state, condition, concept, construct, or event whose value is free to vary, for example, height, dental caries rate, IQ, creativity

1. Independent variable—the treatment or intervention under study; condition that is manipulated or controlled by the investigator; the experimental variable; the experimental treatment; in a non-experimental study, it is the factor studied to explain or predict the dependent variable or the outcome of interest

2. Dependent variable—measure that is expected to change as a result of the manipulation of the independent variable; it is measured to observe the effect of the independent variable; in a non-experimental study, it is the factor or the outcome that is thought to be changed by the independent variable

3. Extraneous variables—uncontrolled variables that may influence the dependent variable and influence (or confound) the outcome, thus interfering with accurate interpretation and producing invalid research results

1. Population—portion of the universe to which the researcher wants to generalize findings; all members of a specific group who possess a clearly defined set of characteristics

2. Sample—a portion of a specific population that, if properly selected, can provide meaningful information about the entire population; a sample is examined when the researcher has no time, money, or resources to study an entire population; a sample may be random or nonrandom and may be representative or nonrepresentative

a. Random sample—composed of study participants who are chosen independently of each other, with known opportunity or probability for inclusion; increases external validity by controlling differences in study participants, which allows for valid generalization of results to the population (reduced bias); results in a representative sample with a homogeneous population

b. Stratified random sample—study participants randomly selected from an existing, known subdivided population; results in the sample proportionately and accurately representing the subgroups in the population; most representative sample for a heterogeneous population

c. Systematic random sample—selection of every nth member of the population from a list or file of the total population; the n depends on the size of the sample desired in relat/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses