Strategies for Oral Health Promotion and Disease Prevention and Control

General Considerations

Dental Hygiene Process of Care1,2

A Dental hygiene practice is based on a process of care that involves the steps of assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation

B Inherent in the process model is a continuum of care that supports a logical system of determining a client’s health and disease status and selecting appropriate interventions

C The dental hygiene process is integrated into the client’s comprehensive dental diagnosis and oral health care plan

Oral Health Education

Basic Concepts

A Initiation and progression of dental diseases depend on the interaction of host, agent, and environmental factors; thus, prevention and control of these diseases require attention to all primary and modifying factors in each category

B Dental caries and the inflammatory periodontal diseases are complex disease states that require the colonization by specific pathogenic bacteria in dental plaque biofilm; none will occur in the absence of pathogenic bacteria in biofilm; thus, the control of plaque biofilm is essential in any oral disease prevention program

C In dentistry, the emphasis is to prevent disease, maintain oral health, and halt disease progression

D Effective preventive programs identify active disease and assess disease risk; clients at high risk for dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral lesions require multiple preventive strategies applied frequently and aggressively (see the sections on “Periodontal disease risk factors” in Chapter 14 and “Caries risk factors” in Chapter 15; see also Table 15-6)

E The prevention of oral diseases requires the participation of clients with adequate knowledge of the disease process and personal level of risk, sufficiently developed skills in implementing oral care procedures, and the motivation to practice preventive behaviors over time to decrease the level of risk

F Many strategies can facilitate changes in the health behaviors of clients; a grasp of the basic concepts underlying educational, motivational, and behavioral theory is necessary to understand the variables influencing a person’s oral health beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors

G Educating clients in effective oral care practices follows the process-of-care model

Appointment Sequencing

A Instructions for the control of dental plaque biofilm are given to the client before any treatment is instituted

1. Clients will see positive changes from their actions (limited soft tissue changes may occur before debridement of tooth surfaces)

2. Improved gingival health can result from improved toothbrushing even in the presence of calculus

3. Clients will recognize the primary importance of self-care

B Biofilm control instructions should be given to the client throughout dental and dental hygiene care

1. Clients need time to practice dental hygiene

2. Clients need time to progress through the stages involved in learning and habituation

3. Evaluation and modifications can occur over time

4. Tissue changes can be demonstrated effectively when treatment and dental plaque biofilm control are integrated

Stages in Making a Commitment to a New Behavior

Learning-Ladder or Decision-Making Continuum

A One approach to mastering the behavior of dental plaque biofilm control is based on the concept that humans learn in a series of sequential steps, referred to as the learning-ladder continuum or the decision-making continuum2

B The dental hygienist first determines the client’s entry level on the ladder and then plans for the client’s moving up the steps in sequence

1. Unawareness or ignorance—client lacks information or has incorrect information about the problem; unmet human need (deficit) in conceptualization and problem solving

2. Awareness—the client knows a problem exists or may occur but does not act on this knowledge; unmet human need (deficit) in responsibility for oral health

3. Self-interest—the client recognizes the problem and indicates a tentative inclination toward action

4. Involvement—the client’s attitudes and feelings are affected, and the desire for additional knowledge increases

5. Action—new behaviors directed toward solving problem are instituted by the client

6. Habit or commitment—new behaviors are practiced over a period and eventually become a lifestyle change

Trans-theoretical Model3

A Conceptualizes behavior change through a series of steps; progression through the steps is dependent on the balance of the advantages and disadvantages of the decision

B Provides a framework to determine and select appropriate interventions to assist clients in improving their health behaviors

1. Precontemplation—the client has no intention of making a change within the next 6 months

2. Contemplation—the client intends to make a change within the next 6 months

3. Preparation—the client intends to make a change within the next 30 days and has taken some behavioral steps in this direction

4. Action—the client has practiced changed behaviors for less than 6 months

5. Maintenance—the client has practiced changed behaviors for more than 6 months

Learning Domains

A To be considered successful, disease-control education must result in behavioral changes; once a client’s learning needs have been assessed, a plan for teaching and learning can be designed

B Three domains of learning have been classified in a hierarchy and are used to specify the learning objectives:

1. Cognitive domain—concerned with knowledge outcomes and the client’s intellectual abilities and skills; the major hierarchical steps are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation

2. Affective domain—concerned with the client’s attitudes, interests, appreciation, and modes of interest; the major hierarchical steps are receiving, responding, valuing, organizing, and characterizing

3. Psychomotor domain—concerned with the client’s technical or motor skills; the major hierarchical steps are perception set, guided response, mechanism, complex overt response, adaptation, and organization

Instructional Principles

See Table 19-14 for dental management considerations with clients who have special needs.

A Effective teaching involves the direction and facilitation of learning to help make positive changes in a person’s behaviors

B To maximize learning, the following principles apply to the design of an educational plan:

1. Small step size—present only what person can assimilate in one session; provide conceptual or factual information when the “need to know” is evident

2. Active participation—provide time and opportunity for the person to ask questions; offer suggestions and monitor the practicing of new skills to enhance learning and retention

3. Immediate feedback—provide the learner with early and frequent information regarding progress; make suggestions for improvement, and use positive reinforcement to support and encourage learning

4. Self-pacing—recognize that each person will progress at a different pace; recognize the learner’s needs, and establish an instructional pace tailored to each client

C Visual aids enhance verbal instructions

1. Use of visual aids available in print, video, internet, or DVD can enhance client comprehension of oral hygiene instructions

2. Demonstration of dental plaque biofilm control techniques on models before intraoral demonstration may be helpful

3. Written instructions and illustrated pamphlets reinforce in-office instructions

4. Clients can access consumer health information from the Internet

5. Use of an intraoral camera that projects images on a monitor enables the client to see the conditions in his or her own mouth

Human Behavior Principles

1. Values form the basis for behaviors

2. Clients come to the dental hygienist with existing values

3. Conflicts between clients’ existing values and those values that support and enable preventive oral health care practices must be recognized and resolved

4. Clients who have value systems that support preventive health behaviors will adopt new behaviors that fit readily into their existing value system

1. Defined as a desire to fulfill an unmet human need (deficit); an inner force that causes a person to act

C Motivation theories—locus of control

1. Internal locus of control—clients feel that they have control over their own outcomes and that their behavior will make a difference; they are most likely to adopt preventive health behaviors

2. External locus of control—clients feel that the outcomes are out of their control and that whatever they do will not affect the outcomes; they are less likely to change behaviors and rely more on the dental professional to take care of their problems

1. Involves explanations given for performance; influences client’s feelings about himself or herself

2. The success or failure at performing a behavior is influenced by the client’s thoughts1

3. Self-efficacy—the client’s level of self-confidence affects his or her belief in the success of performing a behavior

Prevention-Oriented Health Models

Health Belief Model

A Based on the concept that one’s beliefs direct behavior; the model is used to explain and predict health behaviors and acceptance of health recommendations; the emphasis is on the perceived world of a client, which may differ from objective reality

1. Susceptibility—clients must believe that they are susceptible to a particular disease or condition

2. Severity—clients must believe that if they get the particular disease or condition, the consequences will be serious

3. Asymptomatic nature of disease—clients must believe that a disease may be present without their being fully aware of it

4. Benefit of behavior change—clients must believe that effective means of preventing or controlling the potential or current problem exist and that action on their part will produce positive results

C Cues to action—once these beliefs have been accepted, the client will act on them, when necessary; the stronger the beliefs, the greater is the potential that appropriate action will occur

Agent–Host–Environment Theory

A Theory that disease is result of an imbalance in one or all three factors, that is, agent, host, environment

1. Primary—aimed at preventing disease or injury; health promotion activities (such as biofilm control) and specific protection (such as dental sealants and mouth protectors)

2. Secondary—involves early detection and treatment of disease; interventions—such as oral cancer screening programs and regular self-examinations—are designed to stop or minimize the progression of disease in the early stages

3. Tertiary—interventions that prevent disability, restore function, or prevent further destruction of tissues (hard or soft), for example, periodontal or restorative therapies

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

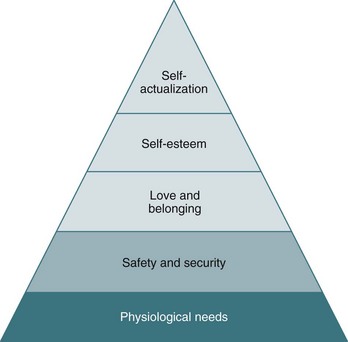

A Theory about human nature that is used to explain the motivational process; Maslow suggested that inner forces (needs) drive a person to action; he classified needs in a pyramid according to their importance to the client, his or her ability to motivate self, and the importance placed on the needs being satisfied; only when a client’s lower needs are met will the client become concerned about higher-level needs; once the needs have been met, they no longer function as motivators (Figure 16-1)

1. Physiologic—survival needs are the most powerful and must be met before any others; include the components necessary for body homeostasis, such as food, water, oxygen, sleep, temperature regulation, and sex

2. Security and safety—these needs are required for protection against physical or psychological damage and are more cognitive than physiologic in nature; include shelter, a job for economic self-sufficiency, and a well-organized and stable environment

3. Social—once the physiologic and security needs have been met, then the needs for love and social belonging become prime motivators; include belonging to a group and having the chance to give and receive friendship and love

4. Esteem or ego—of the two categories of needs that exist at this level, one involves feelings of worth, such as competence, achievement, mastery, and independence; the other involves gaining the esteem of others and triggers learning and the desire to acquire status, power, and higher-level skills

5. Self-actualization or self-realization—these needs drive the client to reach the very top of his or her field; based on positive actions toward development, growth, and self-enhancement

C Application—assessment of a client’s level of needs may aid in the identification of motivational factors that can be targeted for enhancing behavior change

Factors Influencing Client Adherence to Preventive Regimen

A Client–clinician interaction

1. The quality of communication between the client and the hygienist is critical to achieving client adherence

2. Clients must be encouraged to share the responsibility for their oral health

3. Authoritarian or autocratic verbal and nonverbal messages from the dental hygienist will be less effective than messages that allow for genuine client involvement and assumption of responsibility

4. The dental hygienist must recognize that established behaviors are hard to change because they generally satisfy needs; new behaviors are adopted slowly

Prevention Principles for Children

A Proactive counseling of parents about anticipated developmental changes in their children

B Information provided to parents or caregivers in appropriate-sized “bites” on the basis of the developmental milestone anticipated in their children

C Guidance is based on the rationale that people are ready to apply information that is most relevant to them and their children

D Box 16-1 provides suggestions for obtaining compliance from pediatric clients

Dental Plaque Biofilm Detection

General Considerations

A Because dental plaque biofilm is relatively invisible and tooth surfaces are not easily accessed, teaching clients dental disease-control skills can be challenging

B Agents that make biofilm visible supragingivally can enhance the teaching–learning process by:

1. Demonstrating a relationship between the presence of plaque biofilm and the clinical signs of disease

2. Guiding the development of skills that are applied before biofilm removal

3. Allowing evaluation of the effectiveness of skills that are applied after biofilm removal

4. Promoting self-evaluation of skills that are applied by the client at home

C The presence of subgingival plaque biofilm cannot be demonstrated by using disclosing agents

D The plan for disease-control education should include establishing the associations among the presence of plaque, clinical signs of disease such as bleeding, the presence of risk factors, and possible links to systemic disease

E Subgingival biofilm detection by the client is best managed when the client has an understanding of the gingival sulcus (or pocket) and of the clinical changes that occur with ineffective plaque biofilm removal

Disclosing Agents

A Erythrosin (FD&C Red No. 3 or No. 28)

1. A red dye available in tablet or solution form; most widely used agent

2. Can be dissolved into a solution or chewed to dissolve in mouth

3. Tends to stain soft tissues, making post-application evaluation of gingiva difficult

Application Methods for Disclosing Agents

A Solutions are applied with a cotton swab; the tablets are chewed and swished; the client is instructed to rinse and expectorate; single-unit doses are available

B The agents do not stain biofilm-free tooth surfaces unless roughness (i.e., decalcification, pitting) is present

1. Avoid staining restorative materials that may be susceptible to permanent discoloration

2. Dispense the solution into a disposable cup; do not contaminate the solution by introducing applicators into the storage container bottle

3. Erythrosin solutions contain alcohol, which can evaporate over time and alter the concentration of the solution (verify that the client is not an alcoholic, recovering alcoholic, or on Antabuse)

4. To avoid staining the lips, apply a light coat of nonpetroleum or water-based lubricant (e.g., K-Y jelly)

5. Avoid using the agent before application of a dental sealant

6. Avoid any risk of staining clothing, that is, provide appropriate protective drapes to the client, and use small amounts of the solution

Mechanical Plaque Biofilm Control on Facial, Lingual, and Occlusal Tooth Surfaces

Basic Concepts

A Microbial population of dental plaque biofilm contributes to the initiation of dental caries and periodontal diseases

B Mechanical disruption of organized plaque biofilm colonies, both supragingivally and subgingivally, is effective and widely used to prevent and control dental diseases

C Toothbrushing—most widely used and effective means of controlling plaque biofilm on the facial, lingual, and occlusal surfaces of teeth

D Toothbrushes are available in many shapes, sizes, and textures; new designs based on in vivo and in vitro studies, manufacturers’ claims of superior biofilm control, and consumer appeal are being marketed

E The selection of the type of toothbrush should be based on the client’s needs, oral characteristics, and preferences

F Special attention to subgingival plaque biofilm control in areas >3 mm is essential; toothbrushes are generally ineffective in depths >3 mm and in furca; additional tools must be selected

G Toothbrushes should be replaced after 2 to 3 months of use and when filaments become bent or splayed

H Clients who are immunosuppressed, debilitated, or diagnosed with a known infection and those about to undergo surgery should disinfect their toothbrushes or use disposable ones

Manual Toothbrushes

1. Parts include the handle, head, and shank; the head, or the working end, holds clusters of bristles (tufts) in a pattern

a. Handle can be in the same plane with the head or offset at an angle

b. The length varies, with adult brushes being longer than those recommended for children

c. Tuft placement can be in 2 to 4 rows, with 5 to 12 tufts per row; bristles may be of varying lengths

d. The brushing planes can be even, flat, or uneven

e. Many brushes have contoured or thick handles, angled shanks, and flexible heads

a. Natural bristles come from hog or boar hairs and are hollow and nonuniform in diameter, texture, or durability; hollow bristles may harbor bacteria and absorb water, making them soft and soggy with repeated use; these are seldom used today because of their disadvantages

b. Nylon bristles, or filaments, are manufactured for uniformity in texture, shape, and size; nonabsorbent nylon bristles are easily cleaned, dry quickly, and are more durable than natural bristles

c. Relative stiffness—the diameter and length of filaments determine whether the brush will be ranked hard, medium, soft, or extra-soft; variations exist among products from different manufacturers

d. The filament ends (tips) can be cut flat or polished to be rounded

B Desirable characteristics of toothbrushes

1. Conform to individual requirements in size, shape, and texture

2. Easily and efficiently manipulated

C Factors in toothbrush selection and recommendations

2. Recommended method of brushing

4. Client’s age, dexterity, and ability to use the brush in an effective, nontraumatic manner

5. Client’s preference and motivation

6. Unique, special needs of the client (e.g., those with arthritis, Parkinson’s disease; see Chapter 19)

D Soft, multiple-tufted brushes are generally recommended on the basis of their usefulness in both supragingival and subgingival plaque disruption with minimal likelihood of trauma to soft and hard tissues; many toothbrushes have received the American Dental Association (ADA) Seal of Acceptance, the Canadian Dental Association (CDA) Seal of Recognition, or both4

Manual Toothbrushing Methods

A Bass or sulcular brushing method

1. Technique—direct the bristles into the sulcus at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the tooth; vibrate the bristles in a short back-and-forth motion

2. Indications—plaque biofilm disruption at and under the gingival margin; good gingival stimulation; widely recognized as an effective control technique

1. Technique—position the bristles on the attached gingiva and direct them apically at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the tooth; use firm, gentle vibration holding the bristles stationary

1. Technique—place the sides of the bristles on the attached gingiva and direct them apically; turn the wrist to roll or sweep the bristles over the gingiva and the tooth

2. Indications—facial and lingual tooth surfaces; often combined with the Bass, Charters’, or Stillman’s method

1. Technique—position the bristle tips toward the occlusal surfaces at a 45-degree angle to the long axis of the tooth; move the bristles in a short back-and-forth motion

2. Indications—cleaning orthodontic appliances, fixed appliances; following periodontal surgery when sulcular brushing must be avoided to allow wound healing

1. Technique—with upper and lower teeth together, place the bristles perpendicular to the buccal tooth surfaces; use a wide circular motion to cover the gingiva and tooth surfaces of both arches; on the lingual surfaces, use smaller circles to brush each arch separately

2. Indications—when technique must be easy to learn and execute; can be mastered by children

1. Modified-Bass method—combination of Bass and roll methods

2. Modified-Stillman’s method—combination of Stillman’s and roll methods

1. Technique—with teeth in the edge-to-edge position, place the toothbrush bristles perpendicular to teeth; apply a vigorous up-and-down stroke with gentle pressure, followed by a slight circular motion or rotation as the toothbrush strikes the gingival margin; in the embrasure space, apply pressure that is sufficient to force the bristles into the space without damaging the gingiva

Power Toothbrushes

1. Brush heads contain bundles of bristles arranged on a variety of brush head shapes; toothbrushes with different brush head shapes are available on the market

2. The bristles can have flat, bi-level, or multi-level trims; designed for occlusal and smooth surfaces or interdental proximal surface cleaning

3. The handles are larger than those of manual brushes

4. Several power toothbrushes have the ADA Seal of Acceptance or the CDA Seal of Recognition for reduction of plaque biofilm and gingivitis4

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses