CHAPTER 2

Ulceration

• Recurrent aphthous stomatitis

• Epstein–Barr virus-associated ulceration

• Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

• Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

• Radiotherapy-induced mucositis

General approach

• Ulceration of the oral mucosa may be due to trauma, infection, immune-related disease, or neoplasia (Table 1). Vesicullobullous blistering disorders frequently also present as ulceration following rupture of initial lesions (Chapter 3).

• Oral ulcers are invariably painful, although an important exception is SCC, which can be painless, particularly when the tumor is small.

• Ulceration may represent neoplasia and therefore biopsy should be undertaken if there is any suspicion of malignancy or there is uncertainty regarding alternative diagnoses.

• Due to the good vascularity of the oral tissues, the majority of ulcers in the mouth heal relatively quickly. Therefore, any ulcer persisting beyond 14 days should be considered neoplastic until proven otherwise.

Table 1 Patterns of ulceration and differential diagnosis

Single or small number of discrete ulcers

• Traumatic ulceration

• Minor and major recurrent aphthous stomatitis

• Cyclic neutropenia

• Behçet’s disease

• Squamous cell carcinoma

• Necrotizing sialometaplasia

• Tuberculosis

• Syphilis

• Epstein-Barr virus-associated ulceration

• Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws

Multiple discrete ulcers

• Herpetiform recurrent aphthous stomatitis

• Behçet’s disease

• Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

Multiple diffuse ulceration

• Erosive lichen planus

• Lichenoid reaction

• Graft versus host disease

• Radiotherapy-induced mucositis

• Osteoradionecrosis

Traumatic ulceration

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Traumatic causes of oral ulceration may be physical or chemical. Physical damage to the oral mucosa may be caused by sharp surfaces within the mouth such as components of dentures, orthodontic appliances, dental restorations, or prominent tooth cusps. In addition, some patients suffer ulceration as a result of the irritation of cheek chewing. Oral ulceration caused during seizures is well recognized in poorly controlled epileptics. Chemical irritation of the oral mucosa may produce ulceration; a common cause is placement of aspirin tablets or caustic toothache remedies on the mucosa adjacent to painful teeth or under dentures. Situations also occasionally arise where a patient with psychological problems may deliberately cause ulceration in their mouth (factitial ulcers, stomatitis artefacta).

CLINICAL FEATURES

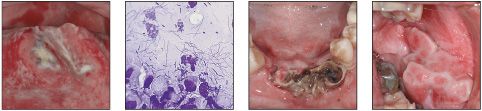

Traumatic ulceration characteristically presents as a single localized deep ulcer (43, 44, 45) with, as would be expected from physical injury, an irregular outline.

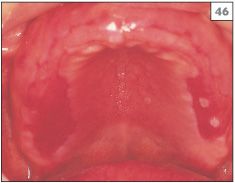

In contrast, chemical irritation may present as a more widespread superficial area of erosion, often with a slough of fibrinous exudate (46).

DIAGNOSIS

The cause of a traumatic lesion is often obvious from the history or clinical examination. Factitial ulceration is usually more difficult to diagnose since the patient may be less forthcoming with the history, therefore a high index of suspicion is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Biopsy is usually required to establish the diagnosis and to rule out infection or neoplasia.

MANAGEMENT

If traumatic ulceration is suspected and it is possible to eliminate the cause, such as smoothing of a tooth or repairing a denture or restoration, and if the mouth can be kept clean, healing will result within 7–10 days. If the lesion is particularly painful, the use of sodium bicarbonate in water or antiseptic mouthwashes, such as chlorhexidine or benzydamine, may be helpful. A biopsy, to exclude the presence of neoplasia such as carcinoma, lymphoma, or salivary gland tumor, should be taken from any ulcer that fails to heal within 2 weeks of the removal of the suspected cause. A patient who is thought to be deliberately self-inducing an ulcer may be challenged with this diagnosis, although admission by the patient is uncommon and the underlying psychological problems should be explored with appropriate specialist help.

43 Ulcer on the lateral margin of the tongue induced by trauma from the edge of a fractured restoration in the first lower molar.

44 Traumatic ulcer on the right lateral margin of the tongue.

45 Irregular ulcer that was self-induced by the patient.

46 Diffuse ulceration in the palate due to the placement of salicylic acid gel by the patient onto the fitting surface of her upper denture.

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

In Western Europe and North America, recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is the most frequently seen mucosal disorder, affecting approximately 15–20% of the population at some time in their lives. Although many etiological theories have been proposed for RAS, no single causative factor has as yet been identified. Hematinic deficiency involving reduced levels of iron, folic acid, or vitamin B12 has been found in a minority of patients with RAS and correction has led to resolution of symptoms. Other predisposing factors implicated include psychoogical stress, hypersensitivity to foodstuffs, cessation of smoking, and penetrative injury. However, in the majority of sufferers it is difficult to identify a definite cause for their RAS.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Clinically, RAS may be divided into three subtypes: minor, major, and herpetiform. All three subtypes share common presenting features of regular, round or oval, painful ulcers with an erythematous border that recur on a regular basis.

The large majority of patients with RAS suffer from the minor form (MiRAS), characterized by either a single or a small number of shallow ulcers that are approximately 5 mm in diameter or less (47, 48). MiRAS affects the nonkeratinized sites within the mouth, such as the labial mucosa, buccal mucosa, or floor of the mouth. Keratinized mucosa is rarely involved and therefore MiRAS is not usually seen in the hard palate or on the attached gingivae. The ulcers of MiRAS typically heal in 10–14 days, without scarring, if kept clean.

Major recurrent aphthous stomatitis (MaRAS) occurs in approximately 10% of patients with RAS and, as the name implies, the clinical features are more severe than those seen in the minor form. Ulcers, typically 1–3 cm in diameter (49), occur either singly or two or three at a time and usually last for 4–6 weeks. Any oral site may be affected, including keratinized sites. Clinical examination may reveal scarring of the mucosa at sites of previous lesions due to the severity and prolonged nature of MaRAS.

Herpetiform RAS, also known as herpetiform ulceration (HU), presents with ulcers similar to those of MiRAS, but in this form the number of ulcers is increased and often involves as many as 50 separate lesions (50). The term ‘herpetiform’ has been used since the clinical presentation of herpetiform RAS may resemble primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, but at the present time members of the herpes group of viruses have not been found to be involved in this or in either of the other two forms of RAS.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of RAS is made relatively easily due to the characteristic clinical appearance of the ulcers and the recurrent nature of the symptoms. A biopsy may be necessary in some patients with MaRAS since a solitary lesion may resemble neoplasia or deep fungal infection.

MANAGEMENT

A wide range of treatment has been recommended for the symptomatic management of RAS. However, in addition to providing treatment to reduce pain and aid healing of lesions, it may be helpful in identifying predisposing factors. All patients with RAS should be advised to avoid foods containing benzoate preservatives (E210–219), potato chips, crisps, and chocolate, since many sufferers implicate these foods in the onset of ulcers. Any relationship to gastrointestinal disease, menstruation, and stress should be investigated. Hematological deficiency should be excluded, particularly if the patient has gastrointestinal symptoms, heavy menstrual blood loss, or a vegetarian diet. Blood investigation should include a complete blood count (CBC) and assessment of vitamin B12, corrected whole blood folate, and ferritin levels. In addition, the presence of celiac disease can be detected in the blood by looking for antigliadin antibodies (AGAs) and tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A (tTG-IgA) antibodies, although these tests are gradually being replaced by the more sensitive test for IgA endomysium antibodies (EMA). Patients may also relate the onset of ulceration to periods of psychological stress.

Many patients obtain symptomatic relief from use of a mouthwash (sodium bicarbonate in water, chlorhexidine, or benzydamine) or application of topical corticosteroid preparations (hydrocortisone, triamcinolone, fluocinolone, beclomethasone, betamethasone). Fluticasone nasal spray used as two puffs twice daily directly onto ulcers when present is particularly useful. A mouthwash based on doxycycline (100 mg capsule broken into water and used as a mouthwash for 2 minutes three times daily for 2 weeks) has also been found to be helpful.

Systemic immunomodulating drugs and other agents such as prednisolone (prednisone), levamisole, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, thalidomide, or dapsone can successfully control RAS, but their use should be considered carefully and they are best prescribed in specialist units for patients who do not respond to topical therapy.

47 Small round ulcer (MiRAS) affecting the labial mucosa.

48 Small round and oval ulcers (MiRAS) affecting the soft palate.

49 Large round ulcer (MaRAS) in the buccal mucosa.

50 Multiple small round and oval ulcers (HU) in the soft palate.

Behçet’s disease

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The etiology of Behçet’s disease remains unclear but is known to involve aspects of the immune system. There is a strong association between Behçet’s disease and the HLA B51 haplotype.

CLINICAL FEATURES

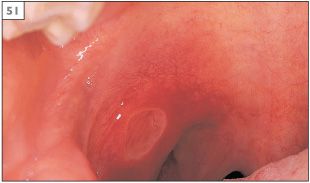

Behçet’s disease is a multisystem condition with a range of manifestations including oral and genital ulceration, arthritis, uveitis, cardiovascular disease, thrombophlebitis, cutaneous rashes, and neurological disease. The condition usually begins in the third decade of life and is slightly more common in males than in females. Behçet’s disease is more common in certain Mediterranean countries and in some Asian countries, especially Japan. The oral lesions consist of ulceration that may be any of the three forms of RAS (51, 52).

DIAGNOSIS

Recurrent oral ulceration is an essential feature of Behçet’s disease, but a number of other criteria are required to be fulfilled to establish the diagnosis. HLA typing may be of value.

MANAGEMENT

Oral lesions should be managed symptomatically in the same way as RAS. The systemic manifestations are managed by the patients physcian.

51 An ulcer of major recurrent aphthous stomatitis in the palate of a patient with Behçet’s disease.

52 Scarring following the resolution of major recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Cyclic neutropenia

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute reduction in circulating neutrophils. Prolonged or persistent neutropenia is associated with leukemia, some blood dyscrasias, many drugs, and radiation or chemotherapy. Cyclic neutropenia is a rare disorder where there is a severe, cyclical depression of neutrophils from the blood and bone marrow. About one-third of cases are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and the remainder arise spontaneously. Studies suggest that the inherited form is the result of a mutation in the gene coding for neutrophil elastase.

CLINICAL FEATURES

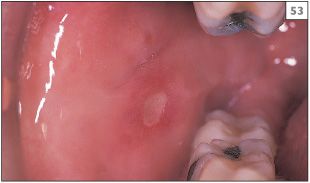

During episodes of neutropenia there is fever, malaise, cervical lymphadenopathy, infections, and oral ulcers. Oral ulceration is common on nonkeratinized surfaces and may appear as single (53, 54) or multiple discrete lesions. Patients are also prone to severe periodontal disease.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is established on examination of the peripheral blood differential, which shows a reduction in circulating neutrophils during episodes of oral ulceration.

MANAGEMENT

There is no specific management for the condition. Medical investigations may be needed to rule out other causes of neutropenia. During episodes of neutropenia, antibiotics may be given to prevent oral infection. Scrupulous oral hygiene is needed to minimize periodontal disease.

53, 54 Minor aphthous stomatitis in cyclic neutropenia.

Squamous cell carcinoma

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The vast majority of intraoral malignancies are cases of SCC. A number of etiological factors have been proposed for SCC but at the present time the two most important are believed to be tobacco and alcohol. The smoking of tobacco in the form of cigarettes, cigars, or a pipe accounts for the majority of tobacco usage and there is a direct relationship between the amount of tobacco used and the risk of developing oral SCC. Although there has been some suggestion that smokeless tobacco is also associated with oral SCC, this link remains weak and controversial. By contrast, the chewing of ‘pan soupari’ (tobacco, areca nut, and slake lime) is a major cause of oral cancer in />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses