Surgery of the posterior mandible

![]() Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Placement of implants in the posterior mandible

General considerations

Treatment planning and diagnosis

Physical examination

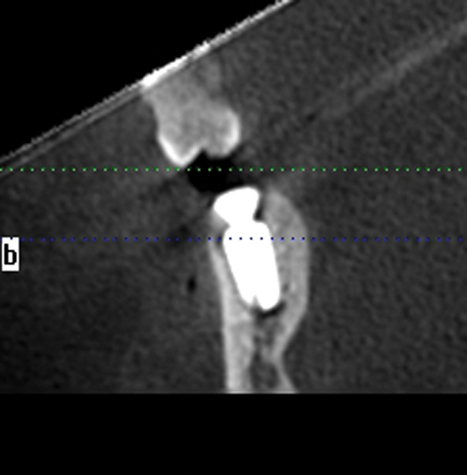

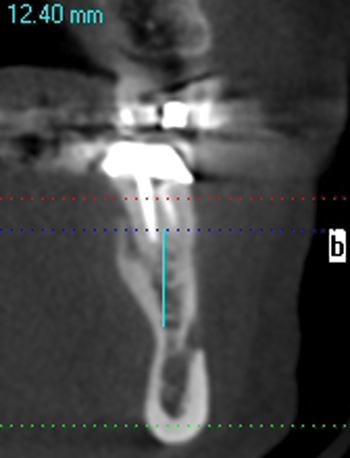

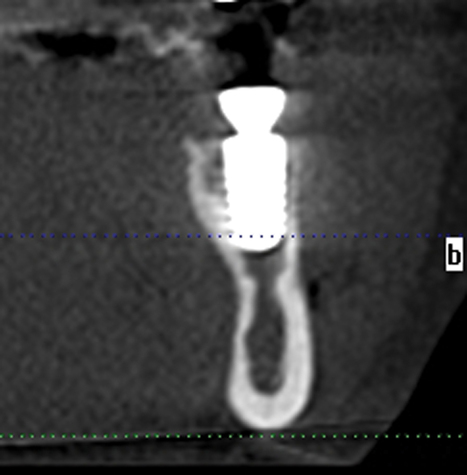

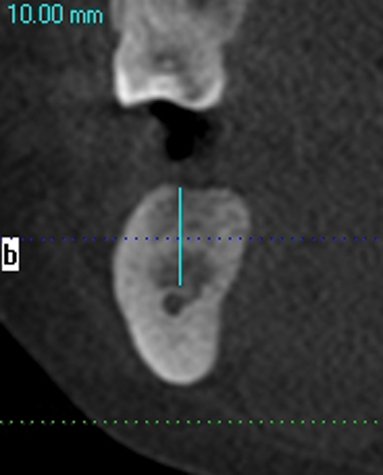

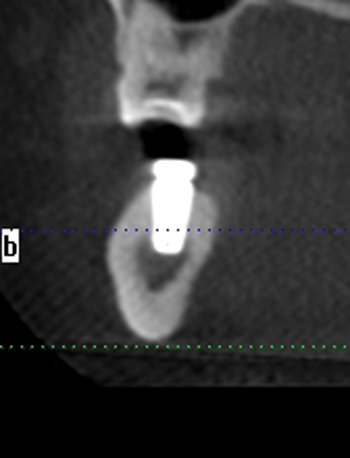

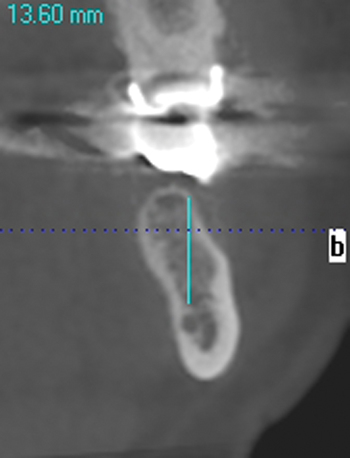

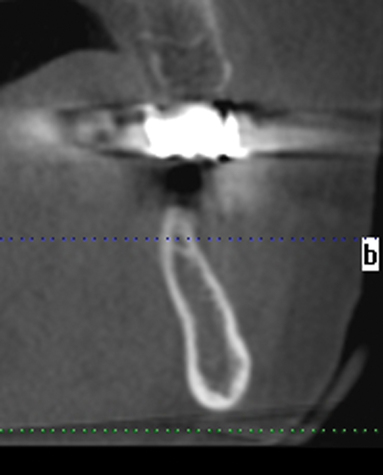

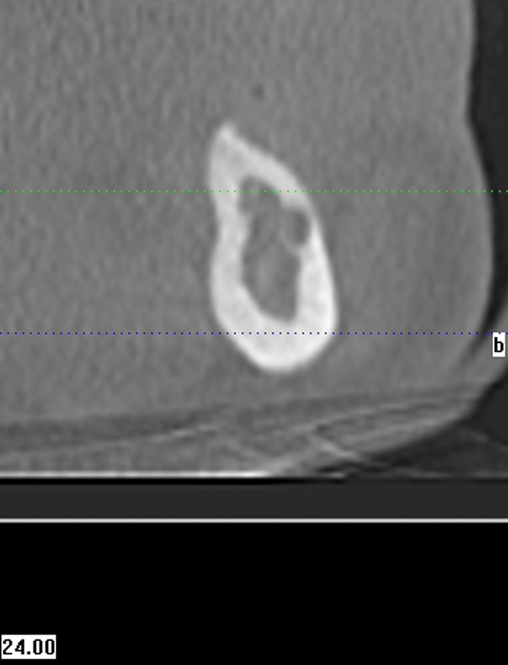

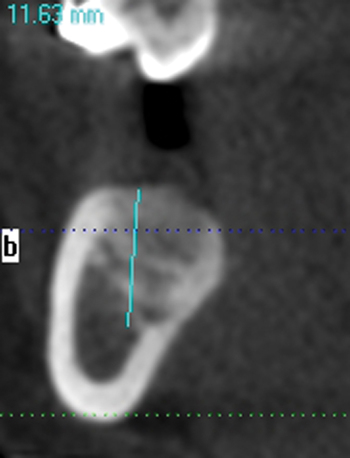

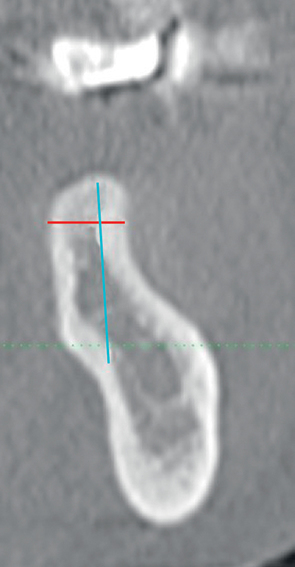

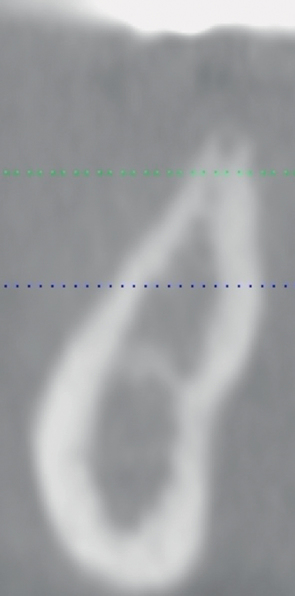

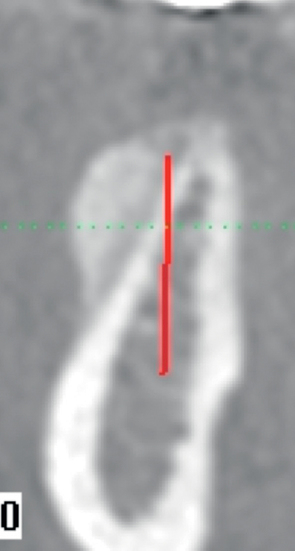

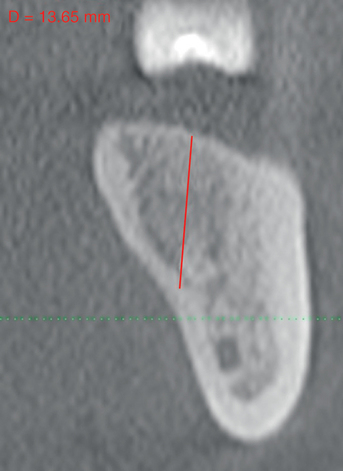

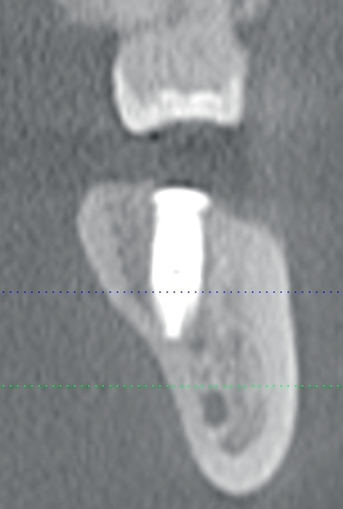

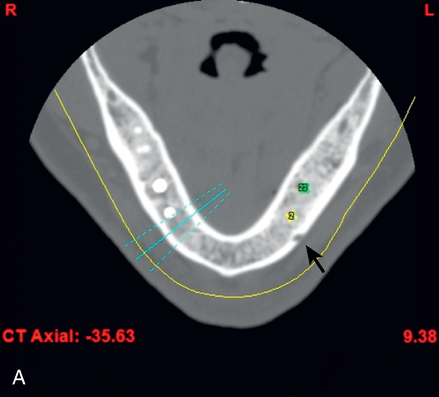

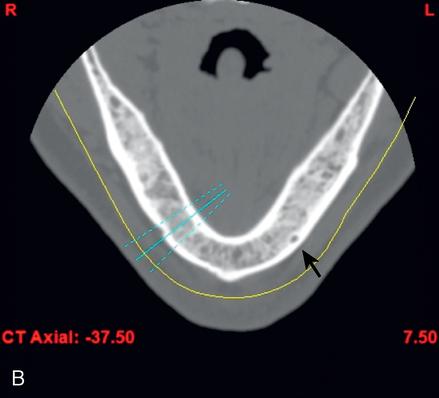

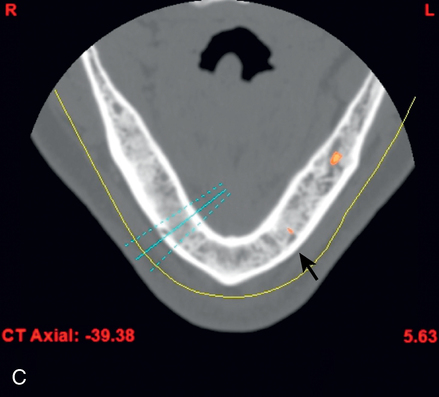

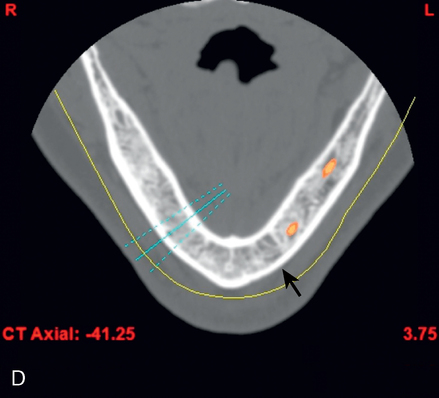

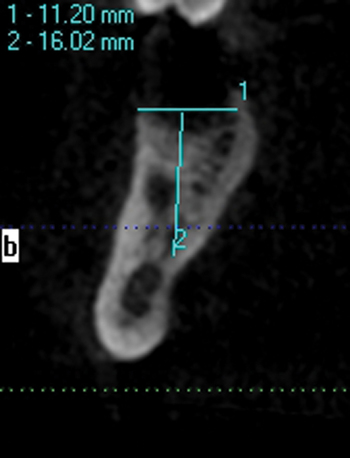

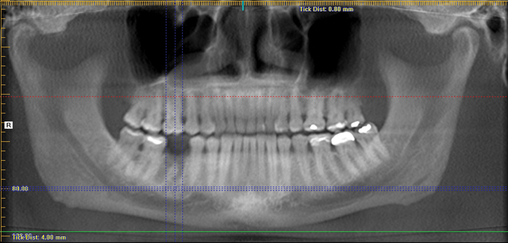

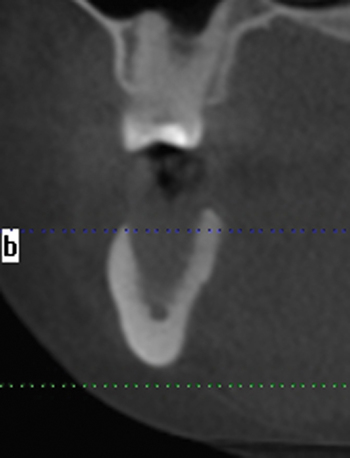

A screening radiograph is obtained. A cone-beam scan with cross-sections is most useful to identify the width of the crest, the sloping of the crest, the location of the internal oblique ridge, and the distance to the inferior alveolar nerve (Figure 2-1). The cone-beam scan is accurate to within 0.5 mm; thus, the magnification issues with panoramic radiographs are not a problem. Traditional panoramic or periapical images simply do not provide the accuracy or cross-sectional views as well as a cone-beam scan. After the radiograph is reviewed, an oral examination is performed to document the following:

2. Masticatory muscle tenderness, if present

3. Presence or absence of teeth

4. Presence of pathologic disorders of the soft tissues of the mandible and maxilla

5. Location of the mental foramen

6. Contour of the edentulous posterior mandible

7. Interarch space between the edentulous ridge and opposing occlusion

8. Width of the keratinized gingiva (KG) on the edentulous region

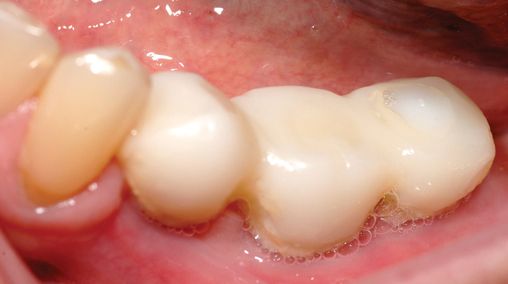

The relationship of the bone to the proposed restoration must be established before the implants are placed. Ideally, the implants should be placed under the surface of the tooth that is receiving the forces of mastication (Figure 2-2). For the posterior mandibular teeth, these are the fossae and buccal cusps. The surgeon should gain an understanding of the relationship of the available bone to the working cusps of the teeth to be restored. With an understanding of the functional loading relationship of implants and bone, the implants can be placed to withstand the forces of chewing. After the posterior mandibular teeth have been extracted, it is common to lose a portion of the thickness of the facial bone. Implants placed too far lingually result in a lingualized occlusion or buccal cusp cantilevers, which may cause abutment fracture after loading. The surgeon may need to graft, restoring buccal deficiencies, to allow placement of implants under the cusps or fossae. Adequate thickness of facial bone allows for a mechanically stable restoration. If grafting is not absolutely indicated because of near-adequate bone position, the implant-supported restoration may be fabricated with a smaller occlusal table to distribute the forces of chewing evenly. To assess whether the patient has a satisfactory amount of bone for the placement of implants into a proper location, a diagnostic setup of the planned restoration may be necessary.

Stent fabrication

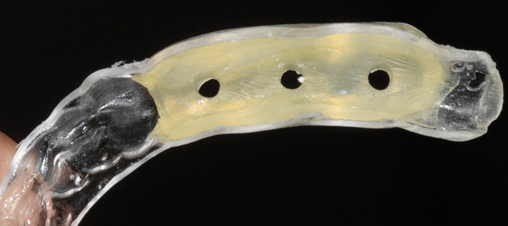

Often the patient has been wearing a removable prosthesis, either as a temporary or a long-term device. If the occlusion is adequate and the teeth approximate the planned anatomic form for the final crowns, the removable prosthesis can be used as a template for the stent. Two impressions are taken, one with and one without the removable prosthesis in the mouth. A thin, plastic vacuum form is made over the stone model of the prosthesis in the mouth. It is removed and trimmed to fit onto the model with remaining dentition only. If the clinician requires a more rigid stent, acrylic can be placed into the hollow cavities of the teeth, as shown in Figure 2-3.

Determination of the number and size of implants

Two premolar teeth can be restored with two implants of regular diameter or small diameter. Two molars can be restored with two wide-diameter implants. In general, the diameter of the implant should be smaller than the diameter of the tooth at the cement–enamel junction. Failure occurs when too few implants are placed and excessive forces of occlusion destroy the bone–implant interface. Implants can be attached to natural teeth, but this has been associated with fracture of the natural teeth or intrusion of the natural teeth.1 It is advised to restore implants with freestanding, implant-borne restorations, avoiding the attachment of implants to the natural teeth.

After the surgical plan has been developed and approved by the patient and restorative dentist, implant placement surgery can be performed. Appropriate consent forms must be signed. A surgical template is fabricated to allow the surgeon to place the implants in line with the fossa or working cusp and to avoid the embrasure spaces of the proposed restoration (Figure 2-4).

Surgical treatment

Placement of implants into adequate bone

This author recommends the use of an antibacterial solution to reduce the flora in the mouth. A chlorhexidine solution is used twice a day for 3 days before surgery to reduce the oral flora.2 Antibiotics are started the evening before surgery. At the time of surgery, a povidone–iodine solution is applied to the surgical site unless the patient has a known allergy to iodine.

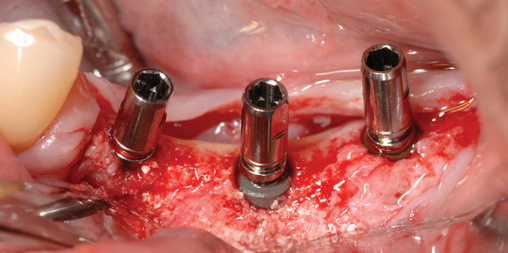

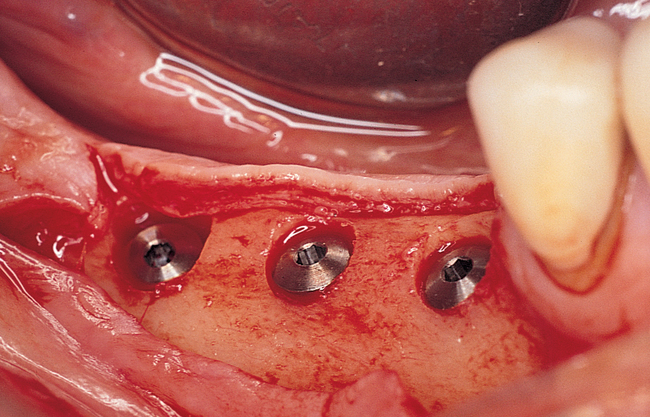

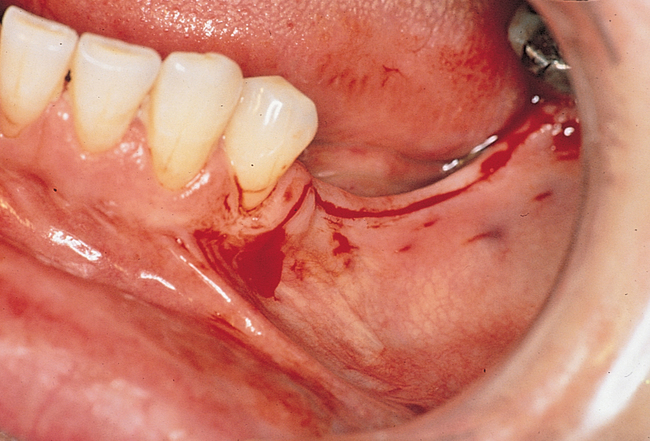

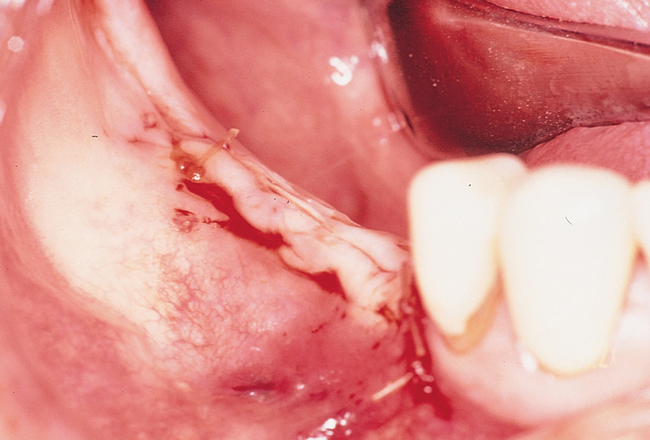

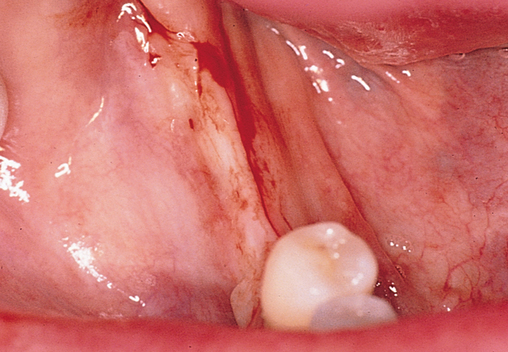

One incision design can be used in most cases. The incision bisects the often thin band of KG (Figure 2-5 and Figure 2-6) because an incision in the posterior mandible occasionally may break down. If breakdown occurs, KG is present on the lingual and labial aspects of the implant. If the incisions are made either lingually or labially to the KG and incision breakdown occurs, the KG will not be present on one aspect of the implant. Bisecting the KG also is used for a one-stage implant, whether the implant is so designed or when a one-stage technique is used intentionally to allow placement of a healing abutment into the implant or immediate provisionalization with a crown. Placement of the healing abutment eliminates the need for second-stage surgery, provides mature gingival tissue over the implant, decreases the number of surgical interventions and hence trauma to the gingiva, and prevents bone overgrowth over the implant.

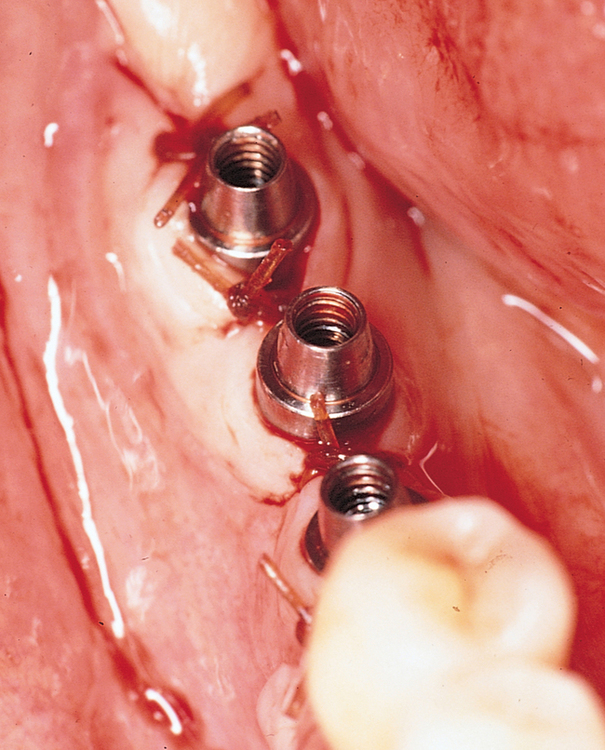

The specific locations for entry of the implants are marked with the surgical guide stent in place (Figure 2-7). These marks are made with a round bur. The stent is removed, and the locations of the drill sites are examined. The center of the implant site should allow the body of the implant to be at least 2 mm from the natural tooth. The surgeon should note the angulation of the roots of the adjacent teeth to avoid apical trauma to the natural tooth because tooth roots can be distal angled. A space of 3 mm should be maintained between adjacent implants to allow for ideal emergence of the crowns from the implants, maintenance of bone between the implants, and adequate healing of the bone to the implant. If the implants are placed too closely together, problems can develop, including difficulty placing the transfer copings and prosthetic abutments, difficulty creating an appropriate hygienic embrasure space, and crestal bone loss from inadequate bone adjacent to the implant.

Placement of implants into single tooth sites with tooth removal

Typically, a patient seeks the extraction of a single tooth that is causing chronic pain, is refractory to periodontal treatment, or is nonrestorable secondary to fracture or caries. A simple algorithm can be used to decide on the timing of treatment. The three scenarios are depicted in Figure 2-8.

If the tooth is “hot,” or has purulent drainage, or has very poor gingival health around the tooth to be removed but has labial and lingual bone present, the tooth is removed without grafting (Table 2-1). After the site becomes pain free and has no exudate, the implant is placed, typically 4 to 8 weeks after removal of the infected tooth. At this time, the implant site is similar to the freshly removed tooth but is not grossly infected. Often the implant can be placed into these sites with minimal flap reflection.

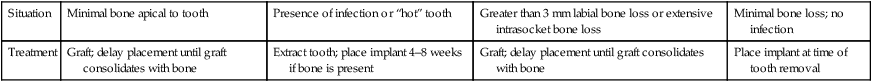

TABLE 2-1

Treatment of the Extraction Site Depending on Clinical Presentation

| Situation | Minimal bone apical to tooth | Presence of infection or “hot” tooth | Greater than 3 mm labial bone loss or extensive intrasocket bone loss | Minimal bone loss; no infection |

| Treatment | Graft; delay placement until graft consolidates with bone | Extract tooth; place implant 4–8 weeks if bone is present | Graft; delay placement until graft consolidates with bone | Place implant at time of tooth removal |

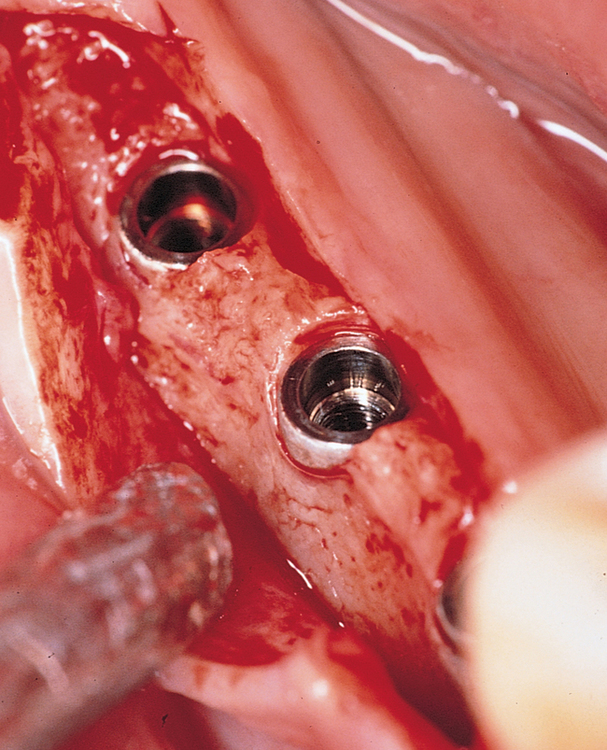

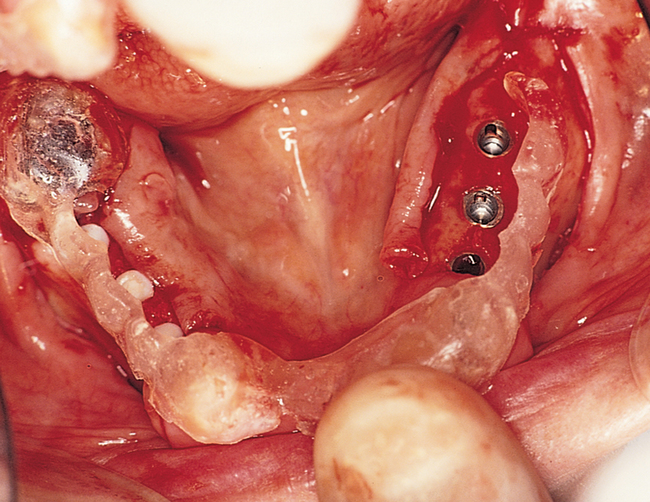

Placement of implants immediately into mandibular molar sites

Placement of a dental implant into the socket immediately after removal of the tooth decreases the time to restoration and provides the patient with one surgical experience. Previous reports on immediate placement of implants into extraction sites in premolar, canine, and incisor locations have indicated excellent implant integration (range, 92%–98%).3 Walker4 reported excellent results with immediate placement of implants into molar sites, concluding that this is a viable procedure. He described a flapless approach with implant insertion torque as the measurement to predict implant success. With insertional torque values greater than 30 N-cm, the implant success rate was greater than 95%. He did not graft the sockets and did not obtain gingival closure over the bone defects. This author has modified the Walker protocol to include a conservative flap elevation to aid in tooth removal and cortical bone preservation, grafting the sockets, and partial coverage of the site with the gingiva that was adjacent to the extracted tooth.5

Surgical technique.

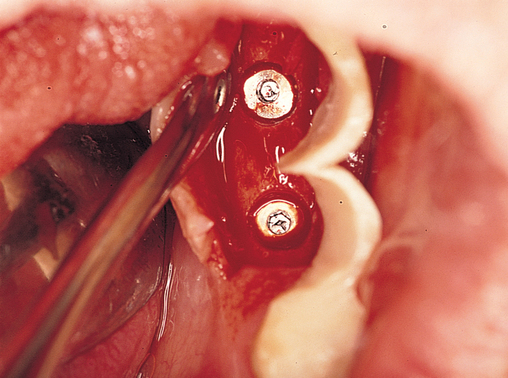

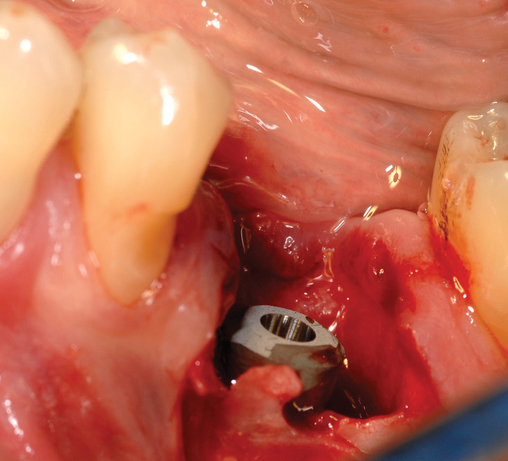

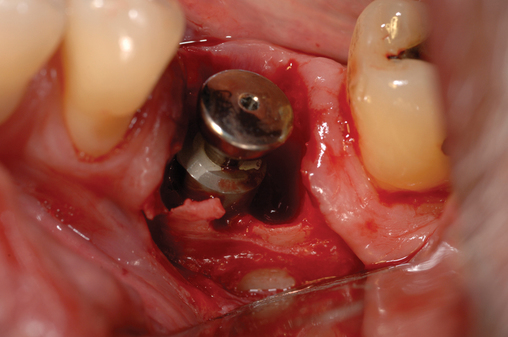

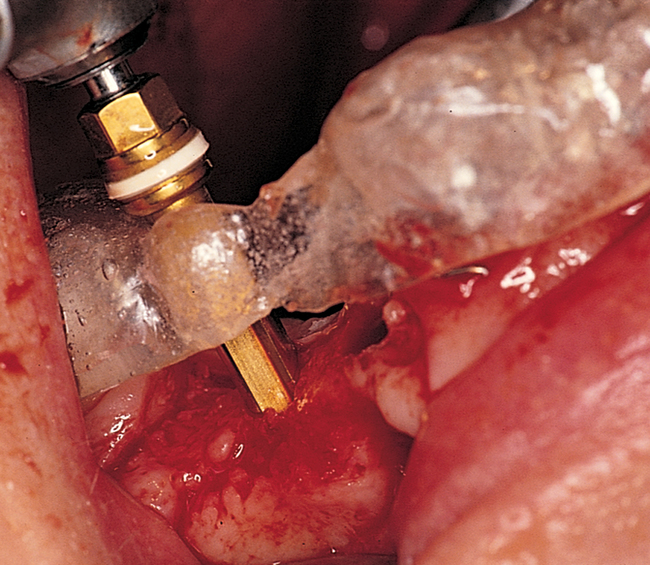

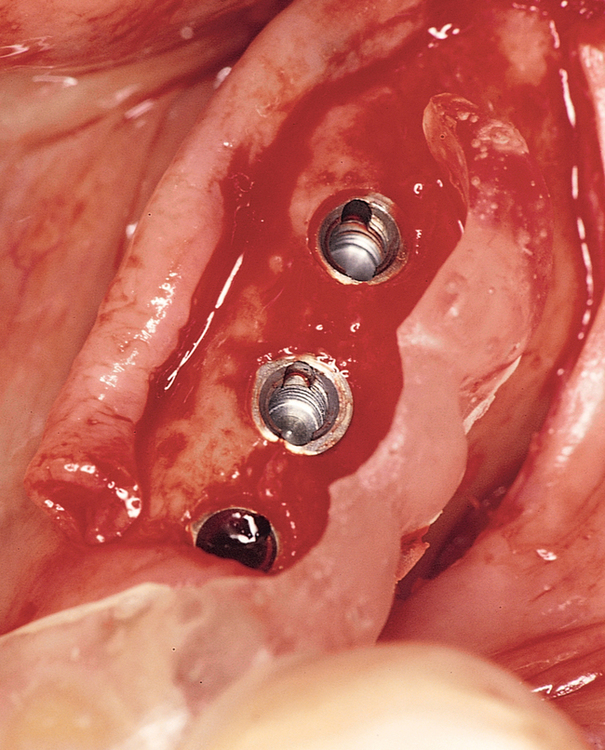

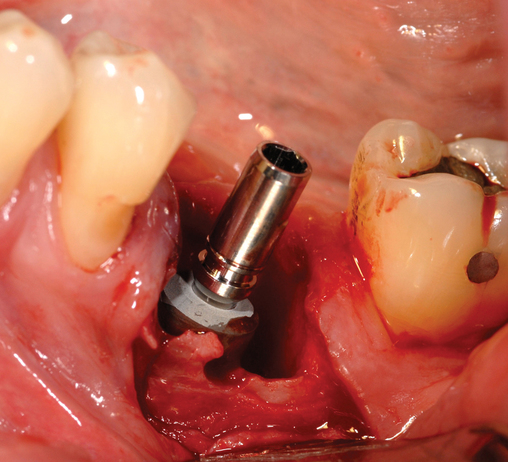

The patient is prescribed chlorhexidine mouthwash to use two times each day for 3 days before surgery to decrease the oral flora.2 Local anesthesia is administered, including local infiltration and block anesthesia as necessary. A sulcular incision is made combined with vertical releasing incisions sparing the attached papilla of the adjacent teeth. If adjacent teeth are present mesial and distal to the molar to be removed, two vertical releasing incisions are made. If the tooth to be removed is the distal tooth, then only an anterior vertical release incision is made, sparing the papilla of the anterior tooth. The flap is reflected to visualize the tooth bone interface. The tooth is then removed (Figure 2-9). When removing the molar tooth, different techniques can be used. The surgeon must preserve the buccal and lingual bone and the interseptal bone. A piezosurgery periotome tip or small drills can be used. This separates the tooth from the labial bone, allowing its removal with minimal loss of bone. The tooth may need to be sectioned with preservation of the interseptal bone. If necessary, bone can be removed along the roots adjacent to the neighboring tooth, mesially and distally. This allows for removal of the tooth root while preserving the buccal or lingual bone. The roots are carefully removed. This may be the most difficult portion of the procedure (see Figure 2-9). After the tooth is removed, granulation tissue is debrided as necessary, and the site is gently irrigated. If epithelial downgrowth has occurred in the socket, this epithelium can be maintained intact; rotated superiorly, preserving its base; and used to cover the site after the implant has been placed. A round bur is used to create a definitive purchase in the desired location of the implant. The implant system’s drills are then used in succession, harvesting autogenous bone from the drills for later bone defect grafting, if present.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses