2

Radiographic Methods Related to the Diagnosis of Impacted Teeth

Qualitative radiography

Three-dimensional diagnosis of tooth position

It is not the purpose of this chapter to present a complete manual on dental radiography, but rather to highlight concisely those techniques and methods that are useful in the clinical setting, as it pertains to impacted teeth. The methods offered have two main aims [1, 2]. The first relates to the furnishing of qualitative information regarding normal and abnormal conditions that may be associated with unerupted teeth. Thus, the different ways of radiologically displaying and recognizing pathological entities, such as supernumerary teeth, enlarged eruption follicles, odontomes, root resorption and other pathological entities, are discussed and compared. The second aim is to describe the various radiological techniques that the clinician may find helpful in accurately pinpointing the position of a clinically invisible, unerupted tooth in the three planes of space. The relative merits of these techniques are discussed and indications for their use are suggested in relation to the different groups of teeth concerned.

Qualitative Radiography

Periapical Radiographs

The first, simplest and most informative X-ray film is the periapical view. This view is oriented to pass through the minimum of surrounding tissue, in order to give accuracy and quality of resolution. It is generally aimed to be perpendicular to an imaginary plane which bisects the angle between the long axis of an erupted tooth and the plane of the film, to produce the minimum of distortion. The periapical film is designed to view the tooth itself from the angle of best advantage, unrelated to its position in space.

From this view, it will be immediately obvious if there is an impacted tooth and if its stage of development is similar to that of its erupted antimere, with at least two-thirds of its root length. The presence and size of a follicle will be obvious, and crown or root resorption, root pattern and integrity will be possible to ascertain. The presence and description of hard tissue obstruction will be evident, allowing the observer to distinguish connate, incisiform and barrel-shaped supernumeraries, and odontomes of the complex or compound composite type. Similarly, it will show soft tissue lesions, such as cysts. The great clarity that the view offers is superior to other views and should always be used as the initial film of a suspected impacted tooth in a radiographic examination. As with any radiographic film, however, the periapical view is two-dimensional, and thus can give no information in the bucco-lingual plane. Overlapping structures cannot be differentiated on a single film as to which is lingual and which buccal.

For this film to give the most advantageous view of the teeth in the maxillary arch and in the mandibular anterior segment, the central ray of the periapical view is oblique, and will vary between 20° and 55° to the occlusal plane [3] depending on the region to be X-rayed. Given this oblique direction, any attempt to estimate the height of an impacted tooth or its bucco-lingual location, without additional information, must fail.

When performing periapical radiography on the posterior teeth in the mandibular arch, however, the most advantageous direction has the central ray very close to the horizontal and as such also offers a true lateral view of these teeth. Thus, not only will the observer see the most precise detail of the tooth and its surrounding tissues, it will also be possible to accurately assess its height in the jaw.

Occlusal Radiographs

Mandibular Arch

In the mandibular arch, this view is properly executed by tipping the patient’s head backwards and pointing the X-ray tube at right-angles to a film, held between the teeth, in the occlusal plane (Figure 2.1). The head will need to be tipped back to permit the positioning of the X-ray tube under the chin. In the lower canine/premolar region, the occlusal view is a ‘true’ occlusal view and should depict all the posterior standing teeth in cross-section, and as such should also provide bucco-lingual positional information on the tooth and any associated structures in a plane at right-angles to that seen on the periapical film. Due to the thickness of bone traversed, detail is much poorer, unless there is expansion owing to a large cyst or a bucco-lingually displaced tooth.

Fig. 2.1 The angle of the central ray in a true occlusal view of the lower jaw depends on the area of interest.

Reproduced from previous edition with the kind permission of Informa Healthcare – Books.

Image not available in this digital edition

In order to produce a true occlusal view in the anterior region of the mandibular arch (Figure 2.1), the head will need to be tipped back further and the tube pointed at the symphysis menti, at an angle of 110° to the horizontal, in line with the long axes of the incisor teeth. To achieve the same for the molar teeth, the 90° angle to the horizontal will need to be augmented by a 15° medial tilt of the tube, to compensate for the characteristic slight lingual tipping of these teeth [3]. This means that, ideally, the film should be performed individually for each side, in order to capture each molar in its long axis and its true occlusal view.

Maxillary Arch

Maxillary Anterior Occlusal

In the maxillary arch, the nose and forehead interfere with the positioning of the X-ray tube, close to the area to be viewed. The best that can be achieved by positioning the tube close to the face is an oblique, anterior, maxillary occlusal view of the teeth, which is perhaps better described as a high or steeply angled periapical view (Figure 2.2). The view will ‘shorten’ the apparent length of the roots, but it will be a far cry from the cross-sectional view that is so easy to achieve in the mandibular arch. Since the central ray passes through cancellous rather than the compact bone that is found in the mandible, detail is usually good, although not as clear as with the periapical view.

Fig. 2.2 A diagram showing incisor inclination, film position and central X-ray beam, differentiating the periapical view, the anterior (oblique) occlusal view and the true vertex occlusal view.

Reproduced from previous edition with the kind permission of Informa Healthcare – Books.

Image not available in this digital edition

True (Vertex) Occlusal

A true occlusal view of the anterior maxilla is a view in which the central ray of the X-ray beam runs parallel to the long axis of the central incisors (Figure 2.3). This is only possible when the cone is placed over the vertex of the skull, to produce the vertex occlusal film. Since the beam has to travel a great distance through the cranium and its contents, the base of the skull and the maxilla, there is a considerable loss in clarity. An excellent alternative method of producing this view, with the film positioned extra-orally, has been described [4]. Notwithstanding, a very long exposure is required, and a fast film should be used in a cassette with intensifying screens. For all these reasons, the method has never been popular. It is, therefore, almost with a collective sigh of relief among professionals that the method has been totally superseded by the introduction of volumetric cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT) scanning. This imaging modality, which can give the same and much more information with little or no increase in radiation dosage, has developed considerable sophistication within a very short space of time and is discussed at the end of this chapter.

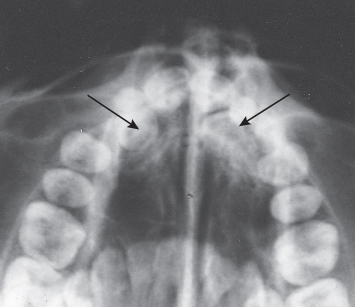

Fig. 2.3 A true vertex occlusal film using Ong’s projection, showing two palatal canines. The right canine is close to the arch and almost vertical. The crown of the left canine reaches the midline suture, while its root apex is close to the line of the arch.

Nevertheless, in this view (Figure 2.3), all the anterior teeth will be seen in their cross-sectional aspect as small circles with a tiny concentric circle in the centre, denoting the pulp chamber and root canal. No information is available regarding the relative height of the object in the alveolus and it certainly cannot be used for fine detail. A single tooth which is palatal to the line of the arch will appear within this arc of small circles. If the tooth is at an angle, not parallel with its neighbours, it will show up in its elliptical, oblique cross-section, representing a tilted long axis. In the event that the tooth is horizontal across the palate, its full length will be obvious on this view, together with the exact mesio-distal and bucco-lingual orientation of both the root and the crown, in the horizontal plane.

The difference may not seem to be very great between the two types of occlusal film, but it should be appreciated that from the vantage point of an anterior occlusal film, the anterior teeth will be foreshortened, but they will still have appreciable length. In this situation, a high and mesially placed labial canine could give virtually the same picture as a low and mesially placed palatal canine. This could not happen in a vertex occlusal projection.

Extra-Oral Radiographs

The panoramic view, while not showing detail to the same degree as a periapical film, has the advantage of simply and quickly offering a good scan of teeth and jaws, from the temporo-mandibular (TM) joint on one side to the TM joint on the other. It is probably true to say that, today, orthodontists are in general agreement that this film gives the most qualitative information to act as a starting point from which to proceed to other forms of radiography, in line with the demands of the particular situation in any given case.

True and oblique extra-oral views (Figure 2.4a–e) and the variously angulated oblique occlusal films all provide information that may be used to complement the periapical film, particularly when tooth displacement is severe. However, the use of any oblique film for the accurate localization of a buried tooth may frequently be misleading, be it a single periapical, an occlusal or a lateral jaw film. This being so, two incipient dangers exist. First, a surgical procedure may be misdirected and a flap opened on the wrong side of the alveolar process. Second, misinterpretation of the tooth’s position may lead the operator to consider there to be a very favourable prognosis for biomechanical resolution when, in fact, the tooth may be in a completely intractable position. Thus, the choice of treatment will be inappropriate.

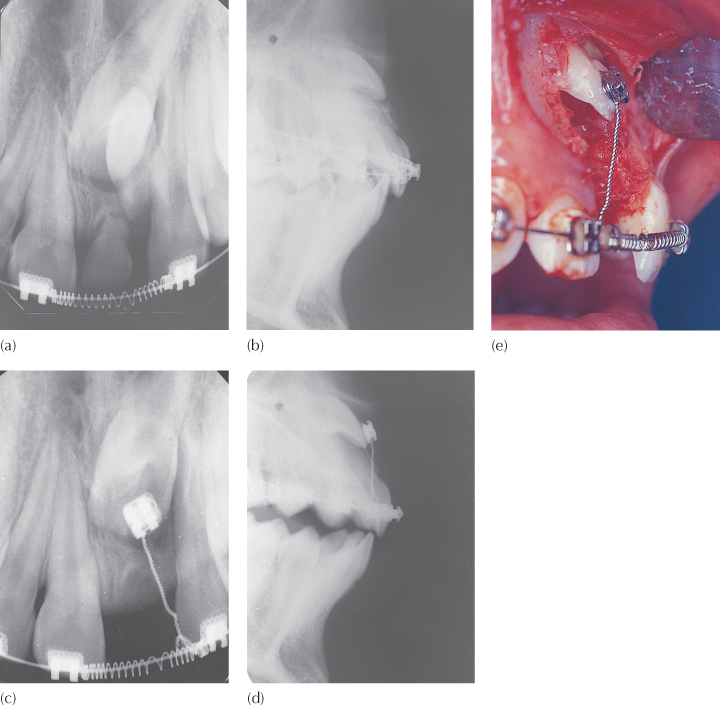

Fig. 2.4 (a) The periapical view shows an impacted left maxillary central incisor, due to an inverted, unerupted, supernumerary tooth. The deciduous tooth is over-retained. Accurate diagnosis of the height of the impacted tooth in the alveolus is not possible from this view. (b) The anterior maxilla seen on a lateral cephalometric radiograph shows the high impacted central incisor, facing the labial sulcus. (c) and (d) The same views as (a) and (b) after removal of the supernumerary tooth and bracket bonding on the exposed incisor. (e) A parallel intra-oral photographic view. The film has been laterally inverted to simplify comparison

(Courtesy of Dr D. Harary.)

Three-Dimensional Diagnosis of Tooth Position

As dentists, we are used to seeing periapical films of individual teeth and, provided that the teeth concerned are erupted and in the line of the arch, these films have many advantages. However, in this view, the X-ray tube is not directed in either the true horizontal, true vertical or true lateral plane. Aside from radiography of the mandibular posterior teeth, the tube is always tipped at an angle to one or more of these planes. For an erupted tooth, this is unimportant, since the third dimension is supplied by direct vision within the mouth. Thus, while it gives a good two-dimensional representation of the tooth, this view has limited value when visualization of an unerupted tooth is required in the three planes of space.

Parallax Method [5]

By following the principles involved in binocular vision, two periapical views of the same object and taken from slightly different angles can provide depth to the flat, two-dimensional picture depicted by each of the films individually (Figure 2.5). This is of considerable help with distinguishing the buccal or lingual displacement of the canine which is low down and fairly close to the line of the arch, and is performed in the following manner (Figure 2.6):

1. A periapical-sized film is placed in the mouth, with the patient’s finger holding it against the palatal aspect of the area where the tooth would normally be situated. The X-ray tube is directed at right angles (ortho-radial) to a tangent to the line of the arch at this point, as for any periapical view, and at the appropriate angle to the horizontal plane for the tooth in question (50° for the central incisor, etc.)

2. A second film is placed in the mouth in the identical position but, on this occasion, the X-ray tube is shifted (rotated) mesially or distally round the arch, but held at the same angle to the horizontal plane and directed at the mesially or distally adjacent tooth. To achieve this, the tube should describe an arc of between 30° and 45° of a circle whose centre is somewhere in the middle of the palate.

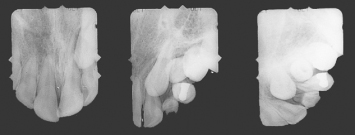

Fig. 2.5 The left periapical view, oriented for the central incisors, shows the crown of the canine superimposed on the distal half of the central incisor root. The middle film, rotated 30° to the left, shows the canine overlapping only the lateral incisor root. By rotating the central beam a further 30°, superimposition of the canine over the lateral incisor root has been eliminated. The canine is palatally displaced.

Fig. 2.6 A diagrammatic representation of the parallax method. If the observer’s eye peers along the axis of the X-ray beam in each case, the image on the film will be easy to reconstruct.

Reproduced from previous edition with the kind permission of Informa Healthcare – Books.

Image not available in this digital edition

There should be no problem identifying which of the two films is the ortho-radial view and which was taken from the distally deviated aspect by studying the relative distortion of the erupted teeth on the two films. However, by radiographically ‘labelling’ the deviated film with the placement of a paper clip in one corner or by using a different film size for the deviated view, such as an occlusal-sized film, this distinction will be simplified.

Let us assume that a right unerupted canine is palatally placed (Figure 2.6), and then this tooth will be close to the middle of the picture obtained in both films. However, in the first picture (direction B), where the tube is directed over the designated canine area of the ridge, the lateral incisor root will be on the right of the picture. If the canine is also mesially displaced, there will be some overlap of the canine crown and the lateral incisor root. On the second picture, taken from the front (direction A), the right lateral incisor root and the crown of the palatal canine will be in the middle of the picture, superimposed on one another, to a much greater degree.

Jacobs [7, 8] enjoins the observer to use the right eye in place of the X-ray tube and suggests the useful exercise of holding up two fingers vertically, at eye level, with one finger obscuring the other. If the observer now closes this eye and opens the other, his/her new vantage point for inspection will have resulted in a visual separation of the two fingers. Through the left eye, the obscured finger will have ‘moved’ to the left of the forward finger, to become partially visible. Transferring this to the radiographic context, in the second picture, the tooth furthest from the tube (i.e. the palatal tooth) will ‘move’ in the same direction that the X-ray tube has travelled from the first exposure.

This method has its limitation, although it is very useful in cases where there is a minimal height discrepancy between the erupted and unerupted adjacent teeth. However, when the canine is high and the periapical view shows no superimposition of the canine with the roots of the erupted teeth, or where the superimposition is only in the apical area, then the overall picture may be very misleading and a different method of localization should be used. The periapical view is directed from above the occlusal plane and in an oblique downward and medial direction, which distances the palatal canine from the roots of the other teeth and makes it appear higher than the anatomy of the maxilla would allow. While it may prove useful in locating the position of the crown of the impacted tooth, it is not adequate to the task of accurately placing the root apex and, thereby, defining the orientation of its long axis. These are important parameters when assessing treatment difficulty and prognosis during the treatment planning stage and critical for the successful resolution of an impacted tooth, as we shall see in the following chapters.

Vertical parallax may sometimes be a useful variant of the same technique, in which two films are taken of the area, with the central ray of one periapical film being more steeply angled in the vertical plane than the other. In this manner, the separation of the images in the more steeply angled (above the occlusal plane) film will result in a palatal tooth being more superiorly related vis-à-vis the target tooth than in the regular film.

Unfortunately, the parallax method in general offers a relatively low degree of reliability. In a study to evaluate the usefulness of its two variants [6], six experienced orthodontists were given the case records of 39 patients with ectopic canines. The cases were evaluated twice, once using films that showed vertical parallax and once with films that featured horizontal parallax, although the parallax pairs were not revealed to the examiners as being of the same individual. In 83% of cases the correct positional diagnosis was made with the horizontal method, while only 68% of cases were correctly diagnosed with the vertical method. These results expose the method as being too crude, or the experts insufficiently discerning, for it to be relied on with any degree of confidence. Thus, while often useful to obtain an initial overall impression, the method should certainly be backed up by more reliable diagnostic radiographic methods before a final treatment plan is presented to the patient.

In the incisor region, an unerupted permanent incisor may be associated with one or two supernumerary teeth (mesiodentes). The parallax method is insufficiently clear in these cases, due to the presence of two or three hard tissue entities in the bone, superimposed on the outline of the roots of the deciduous teeth and at varying heights in the alveolus.

The question arises whether the parallax principles may be applied to other types of film combinations, possibly with a greater degree of reliability. A vertical imaging discrepancy between teeth in the line of the arch and those that are buccally or palatally displaced can be created between the panoramic view and the periapical/anterior occlusal views (Figure 2.7). The panoramic view is a rotational tomograph, with the cone of the machine pointing upwards with a very small 7° tilt from below the occlusal plane, as it circles around the head of the patient. Because this view is recorded when the film is on the buccal side of the teeth and the cone directed from the palatal aspect, this is equivalent to a 7° tilt of the X-ray cone, when translated into a buccal-to-palatal direction.

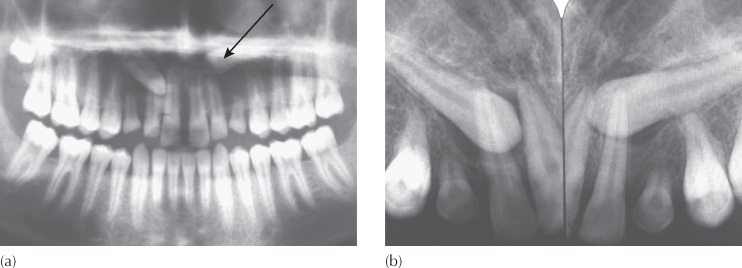

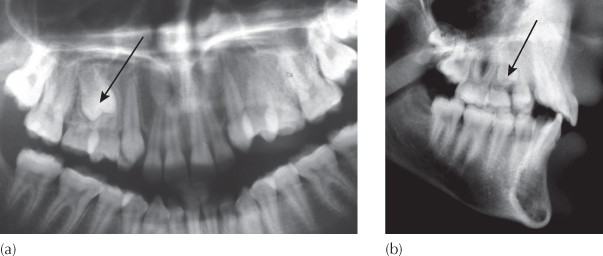

Fig. 2.7 The vertical tube shift method using a panoramic film and periapical views. (a) The panoramic film shows the left canine very high and above the root apices of the incisors (arrow). The right canine superimposes on the apical third of the adjacent incisor. (b) The periapical views show the left and right canines overlapping one-third and two-thirds of the incisor roots, respectively. Both canines are labial.

By contrast, the direction of the central ray in an anterior occlusal (6°–65°) or periapical view (5°–55°) is angulated much more steeply to the film. These will both show superimposition of an ectopic tooth over the tooth in the line of the arch, but a degree of vertical discrepancy between these films and the panoramic view will reveal the position of the displaced tooth.

The same panoramic view will project the anterior midline area in its postero-anterior aspect, with the X-ray beam hitting this area when the cone is at the back of the patient’s head. The canine and premolar regions will be projected from an increasingly angulated viewpoint, as the X-ray cone moves from the back to the side of the head. The molar and retromolar areas will be projected from the side on the same revolving film as the consequence of the further rotation of the X-ray beam.

If all the teeth are in the same approximate semicircular line of the arch, then their mesio-distal relationships will be fairly accurately represented on the film. However, a palatally displaced canine or premolar tooth is imaged when the X-ray cone is at a point in its arc of circle just behind the ear on the opposite side. Viewed from this position, the palatally placed tooth will be ‘thrown’ mesial to its true mesio-distal position and will be shown superimposed more mesially on other structures than would be evident from its appearance on a lateral cephalogram [9]. Accordingly, a panoramic film (an oblique lateral view) and a lateral cephalogram (a true lateral view) may be used together to determine the bucco-lingual location in the canine or premolar regions, in a similar manner to the use of two periapical views in Clark’s parallax method [5]. Obviously, this is dependent on the individual teeth being clearly discernible on the cephalogram, in which unavoidable superimposition in the anterior region may sometimes invalidate the method (Figure 2.8).

Fig. 2.8 The lateral tube shift method using a panoramic film and a lateral cephalogram. (a) In the panoramic view, the X-ray cone projects this image in the premolar area when it is behind the ear of the opposite side and therefore provides an oblique lateral view. This gives the misleading impression that the unerupted right second premolar is rotated. (b) The lateral cephalometric view of the same patient shows only a very mild mesial displacement of the second premolar, with a minimal rotation of its palatal cusp in a mesial direction. Since this film is a true lateral view, this is the true mesio-distal position of the tooth.

One further clue to the position of an ectopic canine is governed by the physical principle that objects projected optically on a screen become markedly larger as the distance between the object and the screen increases, or the distance between the object and the source decreases, with the degree of enlargement being directly proportional to the square of the object–screen distance.

The panoramic X-ray machine is normally adjusted so that its circling of the jaws maintains a fixed distance of the cone to the dental arch, whose perimeter falls within the focal trough of the machine. Teeth which are palatal to the line of the dental arch become enlarged, because they are further from the film and closer to the cone.

The mesio-distal width of a maxillary permanent canine is approximately 90% of the width of the maxillary central incisors. With a normally located canine, the distance between it and the film may be slightly larger than that of the central incisor, due to the form of the arch in that area. Thus, in these cases, it is common to see similar mesio-distal widths of these two teeth on the panoramic film. A buccally displaced canine, on the other hand, will generally reflect the true width difference between the two teeth, because its distance from the film is similar to that of the central incisor (Figure

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses