2

Oral Medicine and Oral-facial Pathology

Case 1

Acute Odontogenic Infection

A. Presenting Patient

- 7-year-old Caucasian male

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint and History of Present Illness

- Child has woken in the morning with a large swelling in the upper jaw.

- Has not eaten or drunk any fluids since previous night (16 hours)

- The child has complained of a toothache for several days and was seen the day before by a dentist who prescribed oral penicillin. Two days later, patient returned to the dental office for extraction but because facial swelling had increased, he was referred to the children’s hospital emergency department for treatment (see Fundamental Point 1).

- How long has the swelling been present?

This swelling has arisen quickly in relation to previous odontogenic pain. The speed of progression of the swelling indicates the acute nature of the pathology or perhaps an acute exacerbation of a previous chronic condition. The size and extent of the swelling is also important. - What is the fluid balance for this child?

Has the child been able to take oral fluids or food? Serious conditions in children may rapidly deteriorate when fluid balance is upset. Children may become dehydrated quickly. The ability to swallow may also indicate the extent to which the swelling involves the airway and the oral cavity. - Has the swelling arisen in spite of the prescription of antibiotics?

This swelling has arisen or increased in the presence of antibiotics. This may aid your diagnosis in that a highly virulent infection may be present, or it may indicate that the swelling is not a result of a bacterial organism. Furthermore, the antibiotics may not be addressing the cause of an infection or the dose and administration of these drugs may be inappropriate. - Is the pain waking the child at night?

The severity of any discomfort can be easily measured by assessing whether it is sufficient to wake the patient from sleep. Children (and most adults) are often unable to fall asleep with severe pain or discomfort and if they wake from sleep, then this is a good indicator of pain.

C. Social History

- Youngest of three children, both parents present

- Middle class family

D. Medical History

- Review of medical history reveals no significant findings, no known food or drug allergies, no medications; vaccinations are up to date

E. Medical Consult

- Infectious diseases

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- Episodic visits to several different local dentists for relief of pain only. No dental treatment provided due to uncooperative behavior.

- Other children in the family have been managed for extensive dental caries under general anesthesia.

- Poor oral hygiene habits, no adult supervision

- Cariogenic diet

- Uses toothpaste containing fluoride

- Lives in optimally fluoridated area

- No history of trauma

G. Extra-oral Exam (see Figure 2.1.1a)

Figure 2.1.1. Facial photograph showing facial swelling

- Examination is difficult because the child is extremely anxious and in pain.

- The child is febrile with a temperature of 38.5°C (101.3°F).

- Large swelling in the canine fossa on the right side of the face extending from the upper lip to the eye. The swelling is firm, red, warm and painful to touch. The eye is closed due to the swelling. The upper lip on the right is also swollen (Figure 2.1.1).

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- Swelling is present and continuous with the extra-oral component, adjacent to the upper right second primary molar

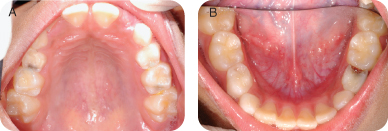

Hard Tissues (Figures 2.1.2ab)

Mixed dentition

- Multiple carious lesions noted on the primary molars

Occlusal Evaluation of Mixed Dentition

- Class I primary canines, class II permanent molars

Other

- Generalized severe plaque accumulation and calculus deposits on lingual surfaces of mandibular incisors

- Multiple extensive carious lesions present. Large carious lesion is present on the mesial of the upper right second primary molar, which is mobile and sore to touch

Figure 2.1.2a–b. Pre-op intra-oral photos. A. Occlusal maxillary, B. occlusal mandibular

I. Diagnostic Tools

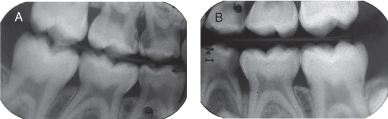

- Bitewing radiographs (Figures 2.1.3a–b)

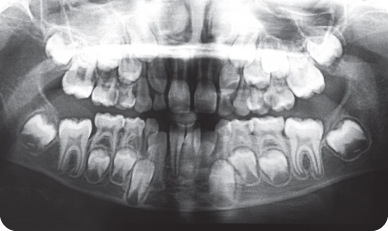

- Panoramic radiograph (Figures 2.1.4)

- It was not possible to obtain a maxillary right periapical radiograph given the patient’s discomfort.

Figure 2.1.3a–b. Pre-op bitewing radiographs. A. Right bitewing radiograph, B. Left bitewing radiograph

Figure 2.1.4. Pre-op panoramic radiograph

J. Differential Diagnosis

Infective

- Odontogenic infection

- Periorbital cellulitis

Immunological

- Insect bite

Neoplasia

- Sarcoma

Inflammatory

- Orofacial granulomatosis

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Odontogenic infection

Problem List

- Acute odontogenic infection presenting with cellulitis

- Febrile illness

- Behavior management difficulties

- Untreated carious lesions in primary dentition

- Lack of dental home

- High caries risk (poor oral hygiene, cariogenic diet, extensive plaque accumulation, no dental home)

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Admission to hospital for commencement of intravenous antibiotics and analgesics, and establishment of fluid balance (see Background Information 1).

- Emergency treatment in the operating room for extraction of teeth and drainage of abscess

- Comprehensive treatment of other carious lesions

- Establishment of a caries prevention plan

- Serious infections should be treated quickly. While the removal of the cause of the infection may suffice in many circumstances, a large facial infection requires administration of antibiotics in appropriate dosage and route of administration.

- Antibiotics may be given in much higher dosages intravenously rather than orally, achieving higher plasma concentrations. An antibiotic of sufficiently broad spectrum should be used initially when the exact nature of an infective organism is unknown or has yet to be determined. Microbiological laboratory culture and sensitivity take at least several days to weeks (in the case of anaerobic infections) to yield results and so prescription of antibiotics is usually empirical.

- What antibiotic can the child tolerate in the oral form? Amoxicillin may be given three times a day with food, while penicillin VK may only be given on an empty stomach four times a day.

- Removal of the cause of the infection must be the mainstay of any treatment plan. The difficulties in treating children arise due to problems with behavior management. It is impossible to drain an infection through the apices of a primary molar tooth.

- Is there a collection of sub or supraperiosteal pus that needs to be drained? Most odontogenic infections in children of this age present as a cellulitis rather than an abscess, in which case there is little or no point in an incision and drainage. Fluctuant swellings usually indicate the presence of pus. Large submandibular swellings involving the first permanent molar may also require incision and drainage.

- If there is a large volume of pus to drain, is an extra-oral incision necessary? Pus will not drain up. Large swellings in the mandible require an extraoral approach.

- Consider what the child can cope with.

- As noted above, any serious infection in the head and neck will probably require admission to a hospital. Hospital admission allows post-operative observation of the patient, allows for the administration of intravenous antibiotics and fluids, and allows monitoring of any complications. Children should only be discharged when fluid intake is adequate and the signs of infection are resolving. Following surgery to the mouth, it is important not to over-hydrate children because they will not feel like taking anything orally, delaying discharge. Maintenance fluids should be kept overnight but then reduced as the child improves to encourage oral intake.

- Always consider the risk of major complications when treating infections in the head and neck. While children improve quickly, they can also deteriorate equally fast when virulent organisms are involved or appropriate treatment is delayed. Such complications include the risk of posterior and/or inferior spread of infection along tissue planes, i.e., cavernous sinus thrombosis and possible brain abscess, spread into the tonsillar fossa, spread into the neck with respiratory obstruction, and/or mediastinal involvement.

M. Prognosis and Discussion

Acute Phase Management

- The essential component of management of this case is the removal of the cause of the infection. Too often cases of acute infection are treated only with antibiotics. While in some cases the administration of antibiotics will resolve the acute phase of the infection, this swelling has increased in the face of antibiotics. The child is acutely febrile and the swelling has increased to close the eye due to collateral edema. Further spread of the infection posteriorly may involve the orbit with the risk of retrobulbar abscess or cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Choice of Management

- This child has had multiple attempts at treatment using routine behavior management techniques. In view of the severity of the infection, management under general anesthesia is the most preferable choice if available. It is recognized, however, that access to this modality of care may not be readily available and so other options such as conscious sedation should be considered.

Choice of Antibiotics

The swelling in this patient has arisen despite the administration of antibiotics, namely penicillin. It is therefore essential to change the antibiotic. Because the child is to be managed under general anesthesia, a first generation cephalosporin is an appropriate alternative. Depending on the severity of the infection, metronidazole could also be added because odontogenic infections are principally of mixed flora with a large Gram-negative component.

N. Complications (Dental)

- Failure of resolution of the infection

- Space loss associated with premature loss of the second primary molar

- Further restorative work required following the acute phase treatment

Self-study Questions

1. What surgical approach would you consider in the management of this child?

2. What alternative antibiotics to penicillin are available in the management of this case?

3. What criteria would you consider for the use of pharmacological behavior management such as sedation or general anesthesia?

4. What long-term maintenance would you consider?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography and Additional Reading

Ellison SJ. 2009. The role of phenoxymethylpenicillin, amoxicillin, metronidazole and clindamycin in the management of acute dentoalveolar abscesses—a review. Br Dent J 206:357–62.

Khanna G, Sato Y, Smith RJ, Bauman NM, Nerad J. 2006. Causes of facial swelling in pediatric patients: correlation of clinical and radiologic findings. Radiographics 26:157–71.

Levi ME, Eusterman VD. 2011. Oral infections and antibiotic therapy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 44:57–78.

López-Píriz R, Aguilar L, Giménez MJ. 2007. Management of odontogenic infection of pulpal and periodontal origin. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 12:E154–9.

Robertson D, Smith AJ. 2009. The microbiology of the acute dental abscess. J Med Microbiol 58(Pt 2):155–62.

Seow WK. 2003. Diagnosis and management of unusual dental abscesses in children. Aust Dent J 48:156–68.

Swift JQ, Gulden WS. 2002. Antibiotic therapy—managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am 46:623–33.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. If there is a significant accumulation of pus subperiosteally, then the elevation of a buccal flap with copious irrigation should be considered. Unlike adults, children typically present initially with a cellulitis rather than a collection of pus. Most of the swelling is associated with collateral edema. Administration of antibiotics alone may localize and wall-off the infection, resulting in the formation of an abscess cavity and further tissue destruction.

2. First generation cephalosporin; Clindamycin, Metronidazole

3. Choice of any behavior management technique relies on the:

- Ability of the child to cope with the treatment required

- Medical contraindications

- Future treatment needs of the patient

- Potential complications

- Presence of trismus

- Local anesthesia issues

4. This child is at a high caries risk and requires a period of familiarization to the dental environment to improve behavior management.

- Establishment of a dental home

- Caries Control and Prevention: Familiarization, fluoridation, oral hygiene practices, diet analysis

- Regular dental follow-up

- Space maintenance as required

- Behavior management

Case 2

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

A. Presenting Patient

- 20-month-old Arabic male

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint

- Child has been ill for two days with a very high fever.

- Child is unable to eat or drink because his mouth is extremely inflamed (see Fundamental Point 1).

- Child has been seen by his general medical practitioner who has prescribed antibiotics and referred to the dentist.

- How long has it been since the child was initially unwell?

- Are any other unwell children in the family or has the child come into contact with any other children, relatives, or caregivers who are also unwell or have similar lesions?

- When was the last time the child had something to eat or drink?

- When was the last time the child urinated?

- Is the child able to sleep at night?

- Does anything relieve the pain or discomfort?

C. Social History

- Youngest of two children, older sister is four years of age and attends preschool

- Cared for by his grandmother during the day

- Low socio-economic status

D. Medical History

- Review of medical history showed no significant findings, no known food or drug allergies, no medications; vaccinations are up to date

E. Medical Consult

- Consultation with general pediatrics regarding fluid balance: The child has not had any fluid intake for more than 12 hours and hence admission to the hospital may be required.

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- First visit to the dentist

- Poor oral hygiene habits

- Cariogenic diet

- Brushes teeth infrequently with some adult supervision

- Lives in an optimally fluoridated area

- No history of trauma

G. Extra-oral Exam

- Examination is extremely difficult due to the state of the child’s health.

- The child is generally unwell, lethargic, and irritable, with a temperature of 39°C (102.2°F).

- There is no extra-oral swelling, but there is marked inflammation and ulceration of the lips and the lateral commissures. Numerous ulcers and open lesions around the lips and face are present (Figure 2.2.1).

Figure 2.2.1. Facial photograph showing facial inflammation and ulcerations

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues (Figure 2.2.2)

- The gingival tissues are acutely inflamed with minor bleeding from the crevicular margin. There are multiple small ulcers, particularly on the dorsum of the tongue, and some areas of ulceration are noted on the attached gingiva. The hard palate, the fauces, and the pharynx are generally unaffected.

Figure 2.2.2. Intra-oral photograph showing gingival inflammation and mucosal ulcerations

Hard Tissue and Occlusal Evaluation

- Deferred at this appointment

Other

- Generalized heavy plaque accumulation

I. Diagnostic Tools

- A swab of the affected tissues could be considered for exfoliative cytology.

- Viral culture (may take many days to establish a result)

- Viral antibody detection

J. Differential Diagnosis

Infective: Viral Infection

- Primary herpetic gingivostomatis

- Coxsackie viral infection: herpangina, and hand, foot and mouth disease

- Other viral infections: infectious mononucleosis (Epstein Barr), varicella (chickenpox)

Immunological

- Autoimmune recurrent ulceration

- Erythema multiforme/Stevens Johnson syndrome

- Behcet’s syndrome

Neoplasia

- Hematological malignancy

Inflammatory

- Orofacial granulomatosis

K. Provisional Diagnosis annd Problem List

Provisional Diagnosis

- Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (see Fundamental Point 2 and Background Information 1)

Problem List

- Acute viral infection

- Febrile illness

- Severe stomatitis

- Pain and discomfort resulting in decrease in fluid intake and possible dehydration.

- The presentation of a young child with a prodrome of one to two days of febrile illness followed by the development of an acute stomatitis is characteristic of primary herpes infection. Typically, vesicles are not seen because they form rapidly and break down to form coalesced areas of ulceration; however, the primary signs are those of acute gingival inflammation. Commonly, the child will present to their local medical practitioner, and antibiotics are frequently prescribed, inappropriately, in the absence of a definitive diagnosis. It is not until the appearance of the ulcers that the true diagnosis is apparent.

- The causative agent in this condition is the Herpes simplex virus. This is usually the type I virus, although the presentation and course of a type II infection is identical.

- Initial infection comes from direct contact with another infected individual and the virus then infects the nerve and remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion.

- Reactivation of the virus results in herpes labialis.

- Because the disease is self-limiting, care should be symptomatic, except in severe cases or children with immune suppression. Acyclovir® has been shown to be effective in control of infection if administered within the first 72 hours of exposure. The usual dosage is 25 to 100 mg/kg/day given five times per day as an oral suspension. Intravenous administration is reserved for severe cases.

- Paracetamol is the most appropriate analgesic to prescribe, in the range of 15 mg/kg up to a maximum of 90 mg/kg/day.

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Admission to hospital for maintenance fluids, mouthwash and debridement, and pain control

- Soft diet as tolerated (see Fundamental Point 3)

- The essential component of management of this case is symptomatic care. Maintenance of fluid balance is essential with a soft bland diet as tolerated. Pain should be controlled with analgesics and there is evidence that the use of topical antiseptics may be beneficial. Non-alcoholic chlorhexidine mouthwash may be used to swab the mouth to debride areas of slough that may be secondarily infected with oral bacteria causing more discomfort. It is advisable to use an aqueous solution of chlorhexidine because some formulations may contain up to 10% ethanol, which is particularly painful when applied to open ulcers.

M. Prognosis and Discussion

- The condition is self-limiting and should resolve within 10 to 14 days. If there is no resolution within this time, then a biopsy is indicated to exclude other conditions. The patient will be prone to recurrent episodes of herpes labialis in times of stress or immune compromise or when the lips are exposed to UV radiation.

- Topical anesthetics and coating agents help relieve pain and facilitate food intake. However, they should be used with extreme caution in children who cannot expectorate because of the potential for traumatic biting and numbness of the gag reflex, if swallowed, which may lead to aspiration.

- Eating ice cream or popsicles may help relieve oral discomfort and increase the fluid intake.

- Maintenance of oral hygiene is essential and it is important to warn the parents/caregivers to use separate utensils, change the child’s toothbrush and pacifiers, etc., and avoid contact with other children.

- Parents should be warned that the child should not touch his eyes. The child must be hospitalized if ocular involvement occurs.

N. Complications

- Dehydration due to inadequate fluid intake

- Recurrent herpes labialis

- Contamination of other body parts (eyes, fingers, etc.)

- Transmission to other family members and children in school and daycare

- Disseminated herpes infection in children who are severely immunocompromised

Self-study Questions

1. When should a child with primary herpes be admitted to hospital?

2. Should an antiviral medication be prescribed?

3. Should antibiotics be prescribed?

4. Will this child have another episode of this type of infection?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography and Additional Reading

Chung NY, Batra R, Itzkevitch M, Boruchov D, Baldauf M. 2010. Severe methemoglobinemia linked to gel-type topical benzocaine use: a case report. J Emerg Med 38:601–6.

Drugge JM, Allen PJ. 2008. A nurse practitioner’s guide to the management of herpes simplex virus-1 in children. Pediatr Nurs 34:310–8.

Krol DM, Keels MA. 2007. Oral conditions. Pediatr Rev 28:15–21.

Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Khoshnevisan MH, Shahiri Tabarestani M. 2008. Acyclovir for treating primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Coch Database Syst Rev 4:CD006700.

Usatine RP, Tinitigan R. 2010. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. Am Fam Physician 82:1075–82.

Wilson SS, Fakioglu E, Herold BC. 2009. Novel approaches in fighting herpes simplex virus infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 7:559–68.

Woo SB, Challacombe SJ. 2007. Management of recurrent oral herpes simplex infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 103 (suppl 1):S12.e1–S12.e18.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. Hospital admission is only necessary if there is a risk of dehydration due to an inability to maintain an adequate intake of fluids. This is an uncommon event; however, the clinician must be aware of the dangers of inadequate fluid balance and should stress to the parents or caregivers that it is essential to encourage the child to drink as much as possible. Intake of solid food is not as important as fluids, but bland soft foods should also be encouraged. Young children will be hesitant to take anything orally in the acute phase.

2. The prescription of antivirals is contentious, and common practice dictates that acyclovir is only effective if administered within the first 72 hours of the appearance of the prodrome. In reality, few children will present to the dentist within this time period and have commonly visited their medical practitioner prior to the dentist. Acyclovir should always be used when managing children who are immunosuppressed.

3. There is really no indication for the prescription of antibiotics in cases of primary herpes because it is a viral infection.

4. Patients will not have another episode of this form of acute infection; however, they will be subject to recurrent cold sores appearing along the terminal distribution of the nerve pathways that have been involved (i.e., the particular division of the trigeminal nerve).

Case 3

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Figure 2.3.1. Facial photograph

A. Presenting Patient

- 7-year-old Hispanic male

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint and History of Present Injury

- The patient recently noticed a purple swelling between his mandibular permanent central incisors. The swelling is painless and occasionally bleeds when brushing the teeth, which is making him unwilling to brush so he will not damage the area (see Fundamental Point 1).

- How long has the swelling been present? When did you first notice it?

- Has it changed in appearance (size, shape, color) recently?

- Has there been any spontaneous bleeding from this swelling or only on brushing?

- Is the lesion painful? Does it hurt spontaneously or only when stimulated?

- Is there anything that makes it better or worse?

C. Social History

- Youngest of three children

- Attends primary school

- Middle class family

D. Medical History

- No significant findings, no known food or drug allergies, no medications, vaccinations are up to date

E. Medical Consult

- N/A

F. Dental History

- Goes to dentist infrequently; last visit was more than 12 months ago

- Has had restorative work done in dental chair

- Poor oral hygiene with no adult supervision

- Normal diet

- Uses toothpaste containing fluoride

- Lives in an optimally fluoridated area

- Normal eruption of teeth with no difficulties in exfoliation of primary teeth

- No history of trauma

G. Extra-oral Exam

- No significant findings

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- Mild gingivitis consistent with poor oral hygiene

- A well circumscribed 7 mm lesion and a large diastema are present between the mandibular central incisors, which have been displaced laterally. The lesion is dark reddish to purple in color but does not blanch or hurt on pressure. The bas/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses