Chapter 2

Endodontic Symptomology and Immediate Management

Aim

To describe the characteristics of symptomatic pulpitis and apical periodontitis, and approaches to their diagnosis and immediate clinical management.

Outcome

After studying this chapter, the reader should have a clearer understanding of endodontic symptomology, diagnosis and rational measures for effective immediate management.

Endodontic Emergencies

Endogenous infection from the oral flora presents a threat to everyone with teeth on a disease continuum from niggling pulp inflammation to potentially life-threatening sepsis. Many patients requiring root canal treatment first present with symptoms of pulp or periapical inflammation requiring diagnosis and immediate management. These patients are usually unscheduled, squeezed into an already busy list of appointments, and easy to mismanage under pressure. Even if extraction becomes the definitive outcome, a simple endodontic procedure can often halt the progression of disease and buy pain-free time to reflect on the final plan of care. Well done, it will also provide a valuable foundation for subsequent endodontic treatment.

Immediate management should be based on the surgical principles of:

-

identifying the cause by reproducing symptoms

-

removing the cause

-

securing drainage of any purulent focus

-

preventing extension.

This may or may not involve the use of antimicrobial or analgesic drugs, which should not be seen as a way of avoiding proper diagnosis and surgical care.

Pulp and periapical infection should not be trivialised and should be treated early and well. Whilst the majority of affluent, dentally aware, fit and healthy individuals probably regard dental sepsis as the stuff of comic cartoons, a significant number of individuals still experience pain and swelling of endodontic origin. Some of these:

-

do not have ready access to routine affordable dental care

-

are immunocompromised by disease or iatrogenically (e.g. following organ transplantation)

-

may be in danger of infection from antibiotic-resistant microorganisms and can be seriously compromised by dental infection (Fig 2-1).

Fig 2-1 What started as an untreated minor niggle.

Common scenarios will be considered under the headings:

-

Symptomatic pulpitis (reversible and irreversible)

-

Symptomatic apical periodontitis (contained and spreading).

Symptomatic Pulpitis

Dental pulps have a rich sensory nerve supply from the trigeminal nerve. Most of the nerve endings are nociceptive, communicating discomfort or pain.

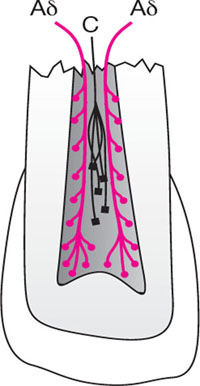

At the periphery of the pulp lie the nerve-endings of Aδ fibres (Fig 2-2), characterised by:

-

low threshold of stimulation

-

fast reaction and conduction

-

communication of sharp, fleeting pain sensation.

Fig 2-2 Location of predominant sensory pain receptors. Fast-reacting Aδ fibres lie peripherally whilst slow-reacting C fibres reside in the core.

These are the fibres stimulated when dentine is exposed to the mouth by gingival recession, traumatic loss of enamel, lost or leaking restorations, or early dental caries.

Pain is usually stimulated by hot, cold or sweet foodstuffs and disappears as soon as the stimulus is withdrawn. A history of Aδ pain usually indicates superficial and minor irritation or inflammation of the pulp; reversible injury which will resolve if the insult can be removed.

More centrally placed are sensory C fibres (Fig 2-2), characterised by:

-

high threshold of stimulation

-

slow reaction and conduction

-

communication of heavy, dull, intense pain, often throbbing in nature.

These are the fibres stimulated by serious inflammation spreading deep into the centre of the pulp. C-fibre pain is often preceded by Aδ pain, and is the classic “toothache”. It can be stimulated by hot, cold and sweet foodstuffs, but unlike Aδ pain, it does not disappear immediately after the stimulus is withdrawn, and will often linger for minutes. It can also appear spontaneously, classically waking patients at night when there is no stimulus in the mouth to provoke it. A history of C fibre pain indicates serious and probably irreversible damage to the pulp.

Symptomatic Pulpitis – Diagnostic Challenges

-

You cannot see it.

Unlike an inflamed finger, the location and condition of a symptomatic pulp cannot be diagnosed by direct visual inspection. Circumstantial evidence may come from the presence of caries or a lost or leaking restoration, but often the culprit is far from clear. -

The patient cannot locate it.

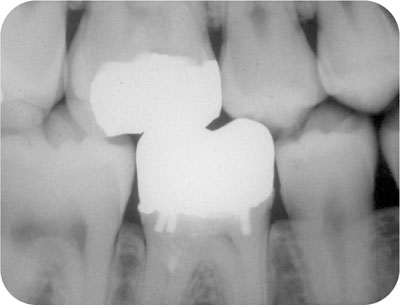

Pulps have no proprioceptive nerve fibres. Usually symptoms are experienced in a general area on one side of the mouth; sometimes pinpointed by rationalisation or referral to a tooth which was treated or troublesome in the past. Referral between the maxilla and mandible on the same side of the mouth is common (Fig 2-3). The unwary or unduly trusting are easily caught out.

Fig 2-3 Poor pain location. Symptoms were rationalised to a lower first molar which was painful and painfully pulpotomised a decade earlier. The offending tooth was actually the opposing upper first molar.

-

Pulpal pain must be reproduced.

Ideally, the patient will not have taken analgesics in the hours before presentation, and an appropriate stimulus should be applied. Patients rarely give a history of “pain on electronic stimulation” and the electronic pulp tester has little or no place in diagnosing the location or state of a symptomatic pulp. Thermal challenges should be applied, either cold or hot, and walked in random order from tooth to tooth in an effort to reproduce symptoms. Pulps under large restorations or thick dentine can be difficult to challenge, and ice-sticks (Fig 2-4) provide a reproducible, profound, durable and inexpensive method. Time usually rules out individual tooth isolation and bathing with a jet of kettle-hot water.

Fig 2-4 Ice-sticks made from local anaesthetic cartridges and floss, or needle sheaths provide an inexpensive, durable and reproducible cold challenge. Used cartridges or sheaths present cross infection risks and should be avoided.

Teeth with enamel-dentine cracks and symptomatic pulpitis are often particularly challenging to diagnose, with sporadic, inconsistent histories of thermal sensitivity and pain on chewing, which does not really represent tenderness to percussion. Their pulpal symptoms can often be reproduced by biting on a wedging device (Fig 2-5), which forces crack flexion, movement of dentine fluid and pain. Symptoms are often most profound on release of biting pressure as the displaced cusp recoils rapidly.

Fig 2-5 Tooth sleuth, one of several commercial wedging devices for the displacement of incomplete tooth fractures and reproduction of pulp sensitivity due to fluid movement in the crack and Aδ nerve stimulation.

Reversible Pulpitis

Reversible pulpitis is characterised by a history and clinical reproducibility of sharp, transient, poorly localised thermal sensitivity (Aδ fibre pain). If the cause is removed, and extension prevented, the pulp should return to health.

Remove the cause

Caries or defective restorations should be removed. If the cause is a crack, its course should be investigated, ideally with transillumination and stains.

Undermined, flexing cusps should be removed for overlay with restorative material.

Prevent extension

The cavity should be sealed, bacteria- and fluid-tight. More than 95% of cases will experience relief from a simple zinc oxide-eugenol cement dressing. It is not currently known if the outcome is better follow/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses