Benign and Malignant Tumors of the Oral Cavity

. Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. ‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. ‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of the Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of the Epithelial Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Connective Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Muscle Tissue Origin

Benign Tumors of Epithelial Tissue Origin

Squamous Papilloma

Clinical Features

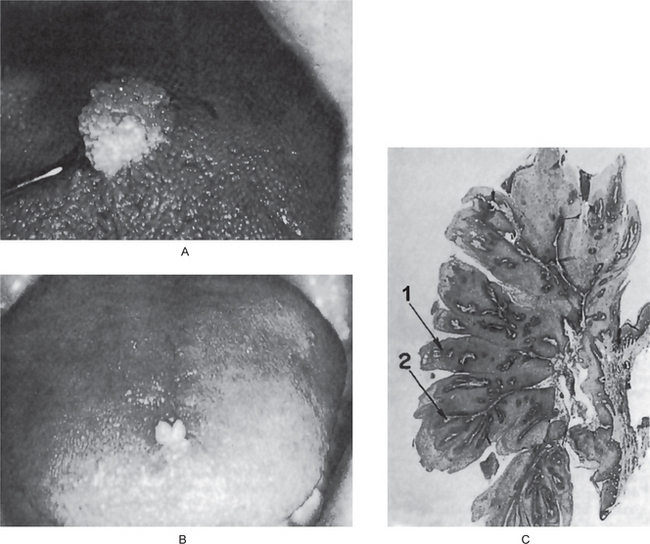

The papilloma is an exophytic growth made up of numerous, small finger like projections which result in a lesion with a roughened, verrucous or ‘cauliflower like’ surface. It is nearly always a well circumscribed pedunculated tumor, occasionally sessile. It is painless, usually white but sometimes pink in color. Intraorally it is found most commonly on the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, gingiva and palate, particularly that area adjacent to the uvula (Fig. 2-1). The majority of papillomas are only a few millimeters in diameter, but lesions may be encountered which measure several centimeters. These growths occur at any age and are seen even in young children. A series of 110 cases has been reported by Greer and Goldman, while a series of 464 cases has been studied by Abbey and his coworkers; this is somewhat indicative of the prevalent nature of the lesion.

Figure 2-1 Papilloma. Large (A) and small (B) papillomas of the tongue illustrate the variation in clinical appearance of the lesion. The photomicrograph (C) illustrates the many finger like projections (1), each containing a thin, central connective tissue core (2), of which the lesion is composed.

The common wart or verruca vulgaris, is a frequent tumor of the skin analogous to the oral papilloma. It is uncommon on oral mucous membranes but extremely common on the skin. The associated viruses in verruca are the subtypes HPV-2, HPV-4 and HPV-40. Clinically it shows pointed or verruciform surface projections, a very narrow stalk, appears white due to considerable surface keratin, and presents as multiple or clustered individual lesions. It enlarges rapidly to its maximum size, seldom achieving more than 5 mm in greatest diameter. Verruca vulgaris is contagious and capable of spreading to other parts of an affected person’s skin or membranes by way of autoinoculation. Lesions that are histologically identical to the verruca vulgaris of the skin are frequently found on the lips and occasionally intraorally (Fig. 2-2). These are often seen in patients with verrucae on the hands or fingers, and the oral lesions appear to arise through autoinoculation by finger sucking or fingernail biting.

Figure 2-2 Verruca vulgaris. These verrucae of the lips occurred in a girl, with similar lesions on the fingers, who habitually bit her fingernails (Courtesy of Dr Paul E Starkey).

Papilloma like or papillomatous lesions as well as ‘pebbly’ lesions and fibromas of various sites in the oral cavity are recognized as one of the many manifestations of the multiple hamartoma and neoplasia syndrome (Cowden’s syndrome). This is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by facial trichilemmomas associated with the gastrointestinal tract, the thyroid, CNS and musculoskeletal abnormalities as well as oral lesions. It is also considered a cutaneous marker of breast cancer.

Histologic Features

The microscopic appearance of the papilloma is characteristic and consists of many long, thin, finger-like projections extending above the surface of the mucosa, each made up of a continuous layer of stratified squamous epithelium and containing a thin, central connective tissue core which supports the nutrient blood vessels (Fig. 2-1 C). Some papillomas exhibit hyperkeratosis, although this finding is probably secondary to the location of the lesion and the amount of trauma or frictional irritation to which it has been subjected. The essential feature is a proliferation of the spinous cells in a papillary pattern; the connective tissue present is supportive stroma only and is not considered a part of the neoplastic element. Occasional papillomas demonstrate pronounced basilar hyperplasia and mild mitotic activity which should not be mistaken for mild epithelial dysplasia. Koilocytes (HPV altered epithelial cells with perinuclear clear spaces and nuclear pyknosis) may or may not be found in the superficial layers of the epithelium. The presence of chronic inflammatory cells may be variably noted in the connective tissue.

Keratoacanthoma (Self-healing carcinoma, molluscum pseudocarcinomatosum, molluscum sebaceum, verrucoma)

Clinical Features

Lesions typically are solitary and begin as firm, round, skin-colored or reddish papules that rapidly progress to dome-shaped nodules with a smooth shiny surface and a central crateriform ulceration or keratin plug that may project like a horn. The lesion appears as an elevated umbilicated or crateriform one with a depressed central core or plug (Fig. 2-3). It is seldom over 1.0 to 1.5 cm in diameter. The lesion is often painful and regional lymphadenopathy may be present.

Histologic Findings

The lesion consists of hyperplastic squamous epithelium growing into the underlying connective tissue. The surface is covered by a thickened layer of parakeratin or orthokeratin with central plugging. The epithelial cells do not usually show atypia but occasionally dysplastic features are found. At the deep leading margin of the tumor, islands of epithelium often appear to be invading and frequently this area cannot be differentiated from epidermoid carcinoma. Lapins and Helwig, among others, have also reported that the keratoacanthoma on occasion may invade perineural spaces, but this does not adversely affect the biologic behavior of the lesion; neither can it be used as a distinguishing characteristic between keratoacanthoma and epidermoid carcinoma. Pseud-ocarcinomatous infiltration typically presents a smooth, regular, well-demarcated front that does not extend beyond the level of the sweat glands. The connective tissue in the area shows chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. The most characteristic feature of the lesion is found at the margins where the normal adjacent epithelium is elevated towards the central portion of the crater; then an abrupt change in the normal epithelium occurs as the hyperplastic acanthotic epithelium is reached. For this reason, the diagnosis may be impossible if the adjacent border of the specimen is not included in the biopsy.

Oral Nevi (Oral melanocytic nevus, nevocellular nevus, mole, mucosal melanocytic nevi)

• Junctional nevus—when nevus cells are limited to the basal cell layer of the epithelium

• Compound nevus—nevus cells are in the epidermis and dermis

• Intradermal nevus (common mole)—nests of nevus cells are entirely in the dermis.

Oral nevi follow the same classification where the term intradermal is replaced by intramucosal.

Clinical Features

The intradermal nevus (common mole) is one of the most common lesions of the skin, most persons exhibiting several, often dozens, scattered over the body. The common mole may be a smooth flat lesion or may be elevated above the surface; it may or may not exhibit brown pigmentation, and it often shows strands of hair growing from its surface (Fig. 2-4). This form of mole seldom occurs on the soles of the feet, the palms of the hands or the genitalia.

Oral Manifestations

Approximately 85% of oral nevi are pigmented. Pigmentation usually varies from brown to black or blue. Nevi are well circumscribed, round, or oval, and are raised or slightly raised in 65–80% of cases. Approximately 15% of nevi are amelanotic. Many amelanocytic lesions appear as sessile growths that resemble fibromas or papillomas or excrescences of normal color.

Histologic Features

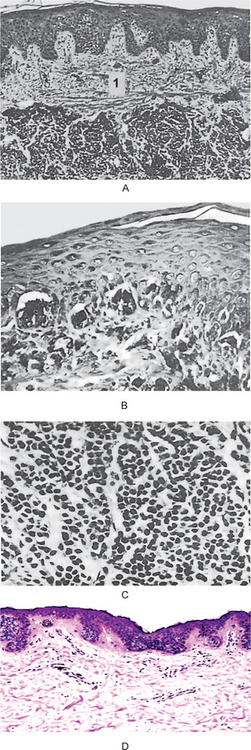

In the intradermal nevus, the nevus cells are situated within the connective tissue and are separated from the overlying epithelium by a well defined band of connective tissue. Thus, in the intradermal nevus, the nevus cells are not in contact with the surface epithelium (Fig. 2-5 A).

Figure 2-5 Pigmented cellular nevus. The intradermal nevus (A) demonstrates a thick band of connective tissue (1) separating the nevus cells from the overlying epithelium. In the compound nevus (B), the nevus cells are in contact with the overlying epithelium and are in the underlying connective tissue. The nevus cells are shown under high magniication (C), Pigmented cellular nevus—nevus cells are in contact with the overlying epithelium and appear to blend into the epithelium (D). (Courtesy of Dr Hari S,Noorul Islam College of Dental Science,Trivandrum )

In the junctional nevus, this zone of demarcation is absent, and the nevus cells contact and seem to blend into the surface epithelium. This overlying epithelium is usually thin and irregular and shows cells apparently crossing the junction and growing down into the connective tissue—the so-called abtropfung or ‘dropping off ’ effect. This ‘junctional activity’ has serious implications because junctional nevi have been known to undergo transformation into malignant melanomas (Fig. 2-5 D).

The compound nevus shows features of both the junctional and intradermal nevus. Nests of nevus cells are dropping off from the epidermis, while large nests of nevus cells are also present in the dermis (Fig. 2-5 B, C).

The blue nevus is of two types: the common blue nevus and the cellular blue nevus. In the common blue nevus, elongated melanocytes with long branching dendritic processes lie in bundles, usually oriented parallel to the epidermis, in the middle and lower third of the dermis. There is no junctional activity. The melanocytes are typically packed with melanin granules, sometimes obscuring the nucleus, and these granules may extend into the dendritic processes. In the cellular blue nevus, an additional cell type is present: a large, round or spindle cell with a pale vacuolated cytoplasm. These cells commonly are arranged in an alveolar pattern.

‘Premalignant’ Lesions/Conditions of Epithelial Tissue Origin

Dysplasia

The histologic connotation to premalignancy is marked by aberrant and uncoordinated cellular proliferation depicted basically at cellular level (atypia), reflections of which could be discerned at tissue levels too (dysplasia). Frequently it is the forerunner of cancer, the causation of this twilight zone in cellular transformation is by no means clear. Dysplasia is encountered principally in the epithelia. “It comprises a loss in the uniformity of the individual cells, as well as a loss in their architectural orientation.” Dysplastic cells exhibit considerable pleomorphism (variation in size and shape) and often possess deeply stained (hyperchromatic) nuclei, which are abnormally large for the size of the cell. The nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio increases from 1:4 to 1:1, at the expense of the cytoplasmic volume. Mitotic figures are more abundant than usual, although almost invariably they conform to normal pattern. Frequently, the mitoses appear in abnormal locations within the epithelium and may appear at all levels rather than in its usual basal location. The usual proliferative organization of the epithelium (see below) is lost and is replaced by a disorderly arranged scramble of cells with varying degrees of differentiation arrest.

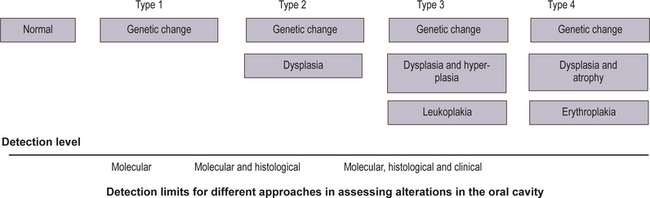

Staging of Oral Precancerous Lesions

An increase in abnormality in either histology or genetic markers was associated with an increase in cancer risk (Fig. 2-6). More recently, studies reported an association of ploidy status (DNA content) in dysplastic lesions with progression risk of oral precancers. The lowest risk was associated with diploid dysplastic lesions (3% progressed into oral squamous cell carcinoma), tetraploid lesions had an intermediate risk (60% showed progression), and aneuploid dysplasia showed the greatest risk (84% progressed). (Lippmann SM, Hong WK, 2001). With time, more such studies will accrue. A future goal will be to determine which combinations of histological and molecular markers best predict risk.

How can such information best be handled? One possibility is to develop staging systems that incorporate different risk factors into risk models. One such model is presented in Table 2-1. For the sake of simplicity, this hypothetical model only includes pathological and molecular markers (clinical features such as appearance, site, and size of the lesion, are not included but should be part of an eventual screening system). In this model, the majority of lesions would be placed into stage 1, with the lowest probability of progressing to cancer. Such lesions would contain both low-risk pathology (P1) and genetic patterns (G1). The emergence of intermediate-risk patterns in either histology (P2) or genetic profile (G2) would place a lesion into stage 2. Stage 3 would contain lesions with a high-risk genetic or histology pattern. It should be noted that the greatest impact of such a staging system would be on lesions in stage 3. Such lesions would now include cases with a relatively benign phenotype (without or with minimal dysplasia) but a high-risk genotype (e.g. P1 G3).

Table 2-1

Staging of oral premalignant lesions with both pathologic and genetic indicesa

| Stage (cancer risk) | Pathology (P)b and genetic (G)c patterns |

| 1 | P1 G1 |

| 2 | P1 G2 |

| P2 G1 | |

| P2 G2 | |

| 3 | P3 G1 |

| P3 G2 | |

| P1 G3 | |

| P2 G3 | |

| P3 G3 |

aAdapted from Zhang and Rosin (2001).

bPathological indices: P1, no dysplasia or mild dysplasia; P2, moderate dysplasia and P3, severe dysplasia/CIS.

cGenetic patterns, categorized by increasing risk: G1, low risk; G2, intermediate risk, and G3, high risk.

Leukoplakia (Leukokeratosis)

• The mucosa is irritated by either mechanical, chemical or galvanic means, and

• The mucosa is trying to adapt to the noxious stimuli by undergoing hyperkeratinization of its surface (good example of tissue adaptation—see earlier paragraphs).

Deinition and Terminology

Definable White Lesions

• Hyperplastic candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). When dealing with a hyperplastic epithelial lesion in which the presence of Candida albicans is demonstrated, it is referred to as candida-associated leukoplakia or others prefer the term hyperplastic candidiasis. In the absence of clinical re-sponse to antifungal treatment, it seems preferable to con-sider such lesion as leukoplakia (van der Waal, 1997).

• Hairy leukoplakia (Greenspan lesion). The term ‘hairy leukoplakia’ is a misnomer due to several reasons. First of all, hairy leukoplakia is a definable lesion. Furthermore, the lesion is not premalignant in nature. Therefore, the use of the term should be abandoned. As an alternative, the term ‘Greenspan lesion’ has been suggested.

• Tobacco-induced white lesions. Smoker’s palate (leukokera-tosis nicotina palati), palatal keratosis in reverse smokers and snuff dippers lesions are clearly related to tobacco use and, therefore, are usually listed as ‘tobaccoinduced le-sions’. These lesions are being regarded as ‘definable le-sions’ and are traditionally not described as leukoplakia. Nevertheless, some of these lesions may transform into cancer.

• Tobacco-associated leukoplakia. The etiological role of to-bacco in patients who smoke cigarettes, cigars or pipes is less obvious. Therefore, preference has been given to the term ‘tobacco-associated leukoplakia’ (leukoplakia in smokers) over the term ‘tobacco-induced white lesions’.

• Idiopathic leukoplakia. One also recognizes nontobacco-associated leukoplakia (leukoplakia in nonsmokers), often referred to as idiopathic leukoplakia.

Etiology

Leukoplakia occurs more frequently in smokers of tobacco than in nonsmokers. There is a dose-response relationship between tobacco usage and the prevalence of oral leukoplakia. Reducing or cessation of tobacco use may result in the regression or disappearance of oral leukoplakia (Gupta et al, 1995). On the other hand, disappearance of oral leukoplakia has occasionally been reported in patients who continued to smoke (Silverman and Rozen, 1968). Tobacco was most often chewed as an ingredient in betel quid (smokeless tobacco or paan) in India. The paan-chewers’ lesion consists of a thick, brownish-black encrustation on the buccal mucosa at the site of the placement of betel quid. It is often seen in heavily addicted betel quid chewers. It could be scraped off with a piece of gauze (leukoplakia); it regresses spontaneously when the habit is discontinued. Due to these reasons the paan-chewer’s lesion does not deserve the designation of leukoplakia. This is a specific entity and rarely progresses to leukoplakia. Whether the use of alcohol by itself is an independent etiological factor in the development of oral leukoplakia, is still questionable. Its effect, at best, may be synergistic to other well-known etiological factors (physical irritants). The role of Candida albicans as a possible etiological factor in leukoplakia and its possible role in malignant transformation is still unclear. About 10% of oral leukoplakias satisfy the clinical and histological criteria for chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Epithelial dysplasia is reported to occur four to five times more frequently in Candida leukoplakia than in leukoplakia in general. However, this change is more common in the speckled variant than in homogeneous leukoplakia and carcinomatous change is more a characteristic of the speckled lesion than that of candidal superinfection. Various kinds of evidence has been presented to justify an etiologic role for candida in neoplastic transformation, which includes, among others, the catalytic transformation in vitro of the carcinogenic nitrosamine, N-nitrosobenzyl-methylamine, by strains of C. albicans demonstrated to be selectively associated with leukoplakia. The possible contributory role of viral agents (human papilloma virus strains 16, 18) in the pathogenesis of oral leukoplakia has also been discussed, particularly with regard to exophytic verrucous leukoplakia (Palefsky JM et al, 1995). In a study from India, serum levels of vitamin A, B12, C, beta-carotene and folic acid were significantly decreased in patients with oral leukoplakia compared to controls, whereas, serum vitamin E was not (Ramaswamy G et al, 1996). Relatively little is yet known with regard to possible genetic factors in the development of oral leukoplakia.

Clinical Aspects

Preleukoplakia is defined as a low-grade or very mild reaction of the oral mucosa, appearing as a gray or grayish-white, but never completely white area with a slightly lobular pattern and with indistinct borders blending into the adjacent normal mucosa (Pindborg et al, 1968).

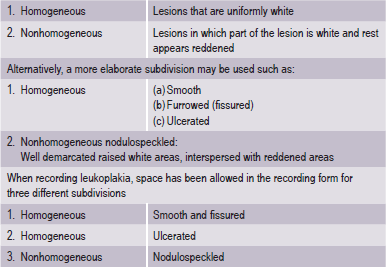

Clinical Classification

It is desirable to record, separately the various forms of leukoplakia and for this purpose subdivisions are recommended (WHO, 1980) (Table 2-2).

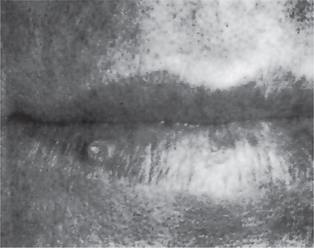

The adjective ‘nonhomogeneous’ is applicable both to the aspect of color, i.e. mixture of white and red changes (erythroleukoplakia) and to the aspect of texture, i.e. exophytic, papillary or verrucous. With regard to the latter lesions, no reproducible clinical criteria can be provided to distinguish (proliferative) verrucous leukoplakia from the clinical aspect of verrucous hyperplasia or verrucous carcinoma. The homogeneous type is usually otherwise asymptomatic, whereas the nonhomogeneous (mixed white and red) leukoplakia are often associated with mild complaints of localized pain or discomfort. In the presence of redness or palpable induration, malignancy may already be present (Fig. 2-7).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Benign Tumors of Nerve Tissue Origin

. Benign Tumors of Nerve Tissue Origin  . Malignant Tumors of Nerve Tissue Origin

. Malignant Tumors of Nerve Tissue Origin