19

Psychiatric disorders

19A General psychiatry

Introduction

What is psychiatry?

PSYCHIATRY: ORIGIN from Greek psukhe ‘soul, mind’ + iatreia ‘healing’.

Psychiatry is the medical specialty concerned with the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and related disorders.

Mental illness is common, affecting up to 1 in 4 people in the UK at some time in their lives. Psychiatrists see only the tip of the iceberg, however, many presenting to other medical and paramedical specialties, remaining in primary care, and some seeking no help at all.

It is therefore extremely helpful for all healthcare workers to have some understanding of the basic concepts of psychiatry, and the nature of psychiatric disorders.

Relevance to dental practitioners

Dentists see patients from all ages, cultures and backgrounds, and may see them in a range of settings. A degree of dental anxiety appears to be present in the general public, and sometimes this can interfere with management.

There is also a range of psychiatric conditions which could cause problems in a consultation and could be avoided if the dentist has an understanding of the most common conditions and how they may present.

Along with doctors and lawyers, dentists are recognised to be a group of professionals at a high risk of mental health problems, including drug and alcohol misuse and suicide. Recognising and understanding problems in yourself or your colleagues may be just as important as it is to recognise and understand it in your patients.

The nature and diagnosis of psychiatric disorder

Psychiatry can seem a confusing specialty – how do we define the conditions treated and how are they distinguished from normality? There are no diagnostic tests, so how is a diagnosis made? If the cause cannot be determined, how can treatment be planned?

There are some conditions for which diagnosis may be aided by investigations, e.g. psychosis due to temporal lobe epilepsy might have the diagnosis confirmed by EEG and a relevant lesion defined on MRI. CT and MRI brain scans can aid the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and other dementias, and these can be verified pathologically at post-mortem. The majority of diagnoses, however, are syndromal, i.e. based on the recognition of a characteristic cluster of symptoms and signs over a defined period of time, sometimes involving the exclusion of underlying physical conditions.

Sometimes a psychiatric illness may in fact be caused by a physical process, such as hypothyroidism. Depression is a recognised feature of hypothyroidism and, in the presence of other symptoms and signs of thyroid disease and abnormal thyroid function tests, a new-onset depression would be considered part of the physical illness and thus ‘organic’ in nature. It would be expected to respond to correction of the underlying endocrine abnormality. A patient with hypothyroidism could also suffer from depression when euthyroid, however, or may have had a pre-existing diagnosis of depression that deteriorated with the decline in function of the thyroid gland. The distinction between these three cases would be made on the basis of the history, in conjunction with thyroid function tests.

Since physical disorders are more reliably diagnosed, organic conditions take precedence in the diagnostic hierarchy of psychiatry.

In the absence of a demonstrable physical cause, however, it must be ensured that syndromal diagnoses are reliable and reproducible. To ensure this, international classification guidelines and schedules have been developed of which two are in common usage. These are:

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10): World Health Organization (1992)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV): American Psychiatric Association (1994).

Table 19A.1 Diagnostic categories from ICD-10 Chapter V (F: Mental & Behavioural Disorders)

| Category | Example |

| Organic mental disorders | Dementia |

| Delirium | |

| Organic mood disorders, e.g. depression due to hypothyroidism | |

| Psychoactive substance use | Acute intoxication |

| Dependence syndromes | |

| Withdrawal states | |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders | Schizophrenia |

| Persistent delusional disorders | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | |

| Mood disorders | Bipolar affective disorder (manic-depression) |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | |

| Dysthymia | |

| Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders | Specific phobias (e.g. dental phobia) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | |

| Hypochondriacal disorder | |

| Atypical facial pain | |

| Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | Anorexia nervosa |

| Bulimia nervosa | |

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | Dissocial personality disorder |

| Histrionic personality disorder | |

| Mental retardation (learning disability) | Down syndrome |

| Fragile X syndrome | |

| Disorders of psychological development | Autism |

| Dyslexia | |

| Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | Hyperkinetic disorder |

| Tic disorder |

ICD-10 was designed for use internationally and is generally preferred in the UK; DSM-IV was developed in the USA. Both systems share predominantly common ground but have some differences. ICD-10 is an aetiological classification with a single axis (see Table 19A.1); DSM-IV is multiaxial (see Table 19A.2), taking account of psychiatric illness, personality, physical illness, psychosocial stressors and level of functioning.

Table 19A.2 DSM-IV

| Axis I | Major mental disorder |

| Axis II | Personality disorder and mental retardation (learning disability) |

| Axis III | General medical conditions |

| Axis IV | Psychosocial and environmental problems |

| Axis V | Global assessment of functioning |

Psychiatric presentations encountered by dentists

As 1 in 4 people will experience mental ill-health during their lifetimes, dentists will invariably come across this in both professional and personal spheres. This could occur in the form of one of the following scenarios:

- the underlying psychiatric condition, e.g. anxiety disorder, is exacerbated by the visit to the dentist

- a psychiatric illness, e.g. psychogenic pain, eating disorders or substance abuse may be detected by the dentist

- a patient may have a psychiatric illness, which may or may not be directly related to the dental presentation

- you or someone you know personally may be affected by a mental illness.

An overview of commonly encountered psychiatric presentations follows, with a summary of other relevant psychiatric conditions, including special mention of children, the elderly and people with learning disabilities.

Anxiety disorders

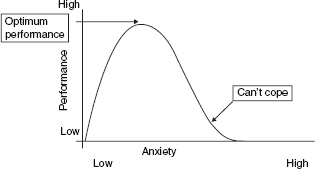

Anxiety is a normal experience in response to a perceived threat or danger. A degree of anxiety is adaptive and can be useful as it serves to mobilise energy reserves for action and enhances performance by increasing arousal (see Fig. 19A.1).

When anxiety becomes too intense, frequent or persistent and as a consequence interferes with a person’s general ability to function, it becomes a problem. It is then said to be ‘pathological’, and part of an anxiety disorder.

Some people are naturally more anxious than others and can be said to have a high level of ‘trait’ anxiety, but certain circumstances will induce a ‘state’ of anxiety in all of us.

Figure 19 A.1 The relationship between anxiety and performance.

Anxiety symptoms can be divided into physical, due to motor tension and autonomic hyperactivity; and psychological (see Table 19A.3).

From a psychiatric point of view, there are several different subtypes of anxiety disorder. These share many common features but vary according to the intensity and frequency of symptoms and the situations in which they occur.

ICD-10 groups anxiety disorders under the heading of ‘neuroses, stress related and somatoform disorders’. Anxiety is probably the psychiatric symptom most likely to be evident in a dental consultation, and relevant conditions will be discussed in more detail below.

Dental anxiety – anxiety related to visiting the dentist

Some estimates suggest that up to 90% of people experience significant levels of anxiety prior to visiting the dentist, with 40% of adults delaying visits because of anxiety. People with dental anxiety tend to be naturally more anxious individuals, although they may be experiencing dental anxiety as part of a generalised anxiety disorder. People with dental anxiety tend to be younger adults and are more likely to be female (see Table 19A.4). Perhaps understandably, it has been reported that in dental anxiety of early onset a previous traumatic dental experience is a major causative factor.

Anticipatory anxiety is common and may be so severe as to prevent attendance at the dentist, with 5% of people avoiding dental appointments completely because of anxiety. This may be a true dental phobia (odontophobia), and in severe cases there may be panic attacks.

Table 19A.3 Symptoms of anxiety

| Psychological | Physical |

| Worry | Gastrointestinal |

| Sense of dread | Dry mouth |

| Irritability | Nausea |

| Poor concentration | Swallowing difficulties |

| Restlessness | Disturbance of bowel habit |

| Cardiovascular/respiratory | |

| Shortness of breath | |

| Chest pain | |

| Palpitations/tachycardia | |

| Neuromuscular | |

| Headache | |

| Light-headedness | |

| Weakness | |

| ‘Jelly legs’ tremor | |

| Muscle aches | |

| Other | |

| Sweating |

Table 19A.4 Dental anxiety – typical patient characteristics

|

|

|

Table 19A.5 ICD-10 diagnostic categories for anxiety relevant to dentistry

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although dental anxiety is common (Table 19A.5), it does not usually cause significant disruption to other areas of daily life and thus does not commonly present to the psychiatrist; indeed the dentist may rarely see this group of people if their avoidance is great enough.

Dental phobia

A phobia is a fear or anxiety which is out of proportion to the stimulus and which cannot be reasoned away. The fear occurs only in specific circumstances and usually in response to a specific stimulus, which can be used to designate the type of phobia, e.g. spider phobia (arachnophobia). Anticipatory anxiety and avoidance of the feared stimulus or situation is typical.

In psychiatric practice, phobic anxiety disorders are divided into three main syndromes – simple phobias (fear of a specific thing), social phobia (fear of social situations) and agoraphobia, a complex phobia frequently associated with panic.

Dental phobia (odontophobia) is a simple phobia and, although common, it is not usually encountered in psychiatric practice.

Anxiety and avoidance

Avoidance of the feared stimulus or situation is one of the central features of a phobic disorder, and indeed of all anxiety disorders. It is understandable that we might wish to avoid situations that make us anxious. In the case of a phobic disorder, it is the phobic stimulus that is avoided, although generalisation to related situations is common; thus the spider phobic will avoid spiders, but their fear may generalise leading to the avoidance of places where spiders may be encountered. A severe dental phobic may avoid visiting the dentist, even when suffering from advanced and painful conditions, and may broaden avoidance to include hospitals and other similar places.

Avoidance results in a reduction of anxiety, but the relief experienced is transient, resurfacing again when confronted with the phobic stimulus or situation, or merely the anticipation of it. Unfortunately the relief experienced serves to reinforce this pattern of avoidance, increasing the likelihood of anxiety being experienced in similar situations in the future. Further avoidance behaviour becomes more likely and the range of situations avoided may broaden.

Management of dental anxiety

As with many conditions, prevention is better than cure. Management should thus be aimed at preventing the condition developing. Generally speaking, the likelihood of attendance at the dentist is not determined by the degree of anxiety experienced during the appointment, but by the degree of anticipatory anxiety prior to it.

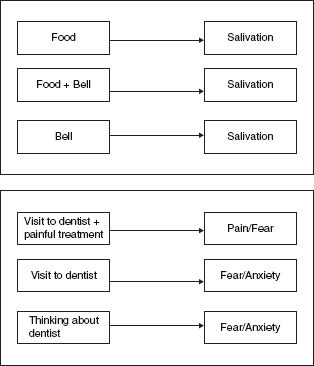

Thinking of anxiety as a conditioned response (see Fig. 19A.2), a traumatic experience whilst visiting the dentist is likely to result in a greater degree of anticipatory anxiety prior to the next visit, thus reducing the likelihood of future attendance.

Pre-existing dental anxiety can be managed using various measures, ranging from simple modification of the environment and clinical approach to more complex psychological techniques. Occasionally medication may be necessary to alleviate anxiety symptoms.

Preventative measures

- Dental health education

- Relaxed, welcoming atmosphere – lighting, pictures, music, etc.

- Calm, sympathetic, paced approach

- Honest, tactful and appropriate explanation of procedures

- Confident and professional manner.

Treatment

- Education regarding anxiety (for patient and dentist!)

- Relaxation techniques/tapes aimed at the subject learning how to relax

- Desensitisation (graded exposure to feared stimulus)

- Medication – anxiolytics such as midazolam may be necessary to facilitate essential dental treatment. Use should be restricted due to potential for dependency

- Alternative therapies such as hypnosis or homeopathic remedies may also alleviate anxiety in some individuals.

Figure 19 A.2 Classical ‘Pavlovian’ conditioning, in which the repeated association of a bell with food leads to a salivation response to the bell alone. In a clinical situation, the pairing of an aversive stimulus (pain) with an otherwise innocuous experience (visit to a dentist or other health professional) leads to an association of that environment with pain.

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

Obsessions are recurrent, intrusive and distressing thoughts, impulses or images. The patient recognises them as coming from their own mind, but regards them as absurd or unpleasant and tries to suppress or ignore them.

Compulsions are the motor response to obsessions and typically take the form of ritualised and often stereotyped patterns of behaviour, such as repeated checking, hand-washing or reciting lists or prayers. Patients typically try to resist carrying out the compulsive behaviours, but completion of the behaviour reduces the anxiety associated with the obsessional thought. The sense of relief associated with this reduction in anxiety acts as a powerful reinforcer, making the compulsive behaviour more likely to be carried out the next time the obsessional thought occurs.

Obsessions and compulsions are the primary features of OCD, although they can also be symptoms of other conditions such as depression.

A typical example of an obsessional thought is the recurrent idea that one’s hands are dirty. This often results in repetitive hand washing that can become so severe that patients have been known to scrub their hands in bleach for hours at a time, until the skin is raw and bleeding.

Occasionally patients will present with obsessional ideas regarding their health, including oral and dental hygiene. This can be difficult to distinguish from hypochondriasis, which is discussed below.

Management of OCD

OCD is less common than other anxiety disorders, but the symptoms are frequently disabling and usually require treatment within psychiatric services. Obsessional thoughts often respond to treatment with antidepressants; compulsions to behavioural therapy. Often a combination of psychological and pharmacological approaches is required.

Hypochondriasis

Hypochondria is one of the oldest concepts in medicine, originally describing disorders thought to arise from disease of the organs lying in the hypochondrium, i.e. beneath the lower ribs.

In current usage, the term describes an abnormal preoccupation with one’s state of health or bodily functions. Patients are typically convinced of the presence of an underlying disease, despite an absence of physical signs or positive investigations, and multiple minor symptoms may be presented as evidence. This is in contrast to somatisation disorders (psychogenic pain, see below) in which the focus is upon the symptoms themselves rather than the underlying disease.

Although people presenting with hypochondriacal states may be suffering purely from hypochondriasis, it is important to remember that they often have another underlying mental disorder, e.g. depression, anxiety disorder or personality disorder. Hypochondriasis is somewhat more common in the lower socio-economic classes and can be a frequent cause of attendance at general medical clinics.

Hypochondriacal ideas regarding the head and neck are common. Patients may present with ideas that they have a specific illness, e.g. cancer, or with a single symptom such as pain, which they present as evidence of illness. Hypochondriasis can present at any age, although the development of these symptoms for the first time in middle or later life would increase the possibility of an underlying depressive or organic disorder.

Sufferers tend to observe and interpret normal bodily experiences in an abnormal manner, with a hypersensitivity to otherwise normal bodily sensations, e.g. noticing a dry mouth and interpreting this as indicating the presence of kidney failure.

Management of hypochondriasis

It is often very difficult to persuade people that their symptoms might have a psychological component. Such suggestions are frequently met with hostility by the patient who feels that appropriate care is not being offered and may visit other practitioners seeking further opinions on their condition.

The foundation of good management is therefore in establishing a reliable diagnosis, although it is unlikely that this diagnosis will be made at the first contact.

As people present with a physical rather than a psychological complaint, their symptoms must be taken seriously and physical examination and investigations should be undertaken to exclude physical disease. A degree of caution is advised, however, as inappropriate investigations ordered at the patient’s request are often inadvisable as they merely reinforce the patient’s idea that he is physically ill.

If hypochondriasis is suspected, it is advisable to seek psychiatric help from an early stage, as the nature of the condition is such that prolonged investigations and repeated assessments reinforce the illness beliefs and may in fact exacerbate the condition. Hypochondriasis can be difficult to treat, but treatment aims to address any underlying disorder, and may include pharmacological as well as behavioural and psychological measures. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be useful.

Treatment outcome is better in those with an underlying, treatable psychiatric disorder such as depression or anxiety and in those whose symptoms are of most recent onset. Chronic cases have a poor prognosis, and management options may be limited to minimising any harm that might inadvertently be caused as a result of unnecessary investigations.

Psychogenic pain

‘Psychogenic’ pain is pain in which the cause is psychological rather than physical, although this may not be evident to the patient. It can be thought of as a physical manifestation of unarticulated psychological distress (Table 19A.6). For the sufferer, however, the perception and sensation of pain is very real, may be severe and excruciating, and should not be dismissed.

Table 19A.6 Features suggestive of psychogenic pain

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Many medical practitioners imagine that pain of psychological origin is likely to be bizarre in character and unlike ‘real’ pain of identifiable organic origin. Unfortunately, this view is inaccurate and may be unhelpful.

A psychological origin may, however, be suggested by the presence of certain characteristics. Whilst these may arouse suspicion, diagnosis requires clear evidence of a psychological cause in conjunction with exclusion of an underlying organic process.

Perhaps up to 50% of psychogenic pain is experienced as occurring in the head, and as such it is highly pertinent to the practice of dentistry. Psychogenic pain syndromes present 4–5 times more commonly in females, and typically present in middle age, often post-menopausally.

Management of psychogenic pain –general principles

Correct diagnosis is very important. It should follow appropriate investigation and be based upon an absence of organic pathology in the presence of evidence of a possible psychological cause. It may take some time to establish this diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis has been made, underlying psychiatric conditions should be sought and treated appropriately. Anxiety and depression are recognised causes of psychogenic pain, but it is important to be aware that both may actually be secondary to chronic pain.

There are at least four pain syndromes pertinent to dentistry which may have a significant psychological component. They may present as distinct syndromes or co-exist in the same patient (Table 19A.7).

Atypical facial pain

Atypical facial pain is a syndrome of often poorly localised pain, which is typically described vaguely as a deep, dull ache and does not fit a classical anatomical distribution. The exact nature of the psychological component of this disorder is unclear, but it is commonly associated with other recurrent symptoms such as back ache and features of depression.

Table 19A.7 Dental psychogenic pain syndromes

|

|

|

|

Atypical facial pain is best treated according to the general principles of psychogenic pain management outlined above. There is evidence that antidepressant medication can be effective, particularly tricyclic antidepressants. Tricyclics such as amitriptyline should be used with caution, however, due to the high incidence of side effects and toxicity in overdose. Newer, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants may also be useful, particularly if there is an underlying depressive illness, and there is an increasing body of evidence for CBT in the management of chronic pain syndromes.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome

TMJ dysfunction syndrome is a heterogeneous syndrome that may be the final common pathway for a number of other conditions. It presents most commonly in young female adults. Frequently reported symptoms are a prolonged dull ache in the muscles of mastication, with associated tenderness, earache and/or TMJ pain. It may be bilateral or unilateral and can be associated with joint ‘sticking’ or clicking and popping, trismus, bruxism and tinnitus. There would appear to be a subgroup of people with a significant psychological disorder, typically anxiety or depression, which may sometimes precede the onset of the pain by 6 months or more.

Management is similar to that for atypical facial pain and depends upon the relative balance of psychological and physical components.

Atypical odontalgia

Atypical odontalgia may be considered as the dental variant of atypical facial pain. The pain may be aching, burning or throbbing and tends to affect the molars and premolar teeth as well as the jaw, and the maxilla more often than the mandible.

A proportion of such cases may be attributed to deafferentation and may be neuropathic, but many are felt to be idiopathic and unrelated to dental procedures or trauma.

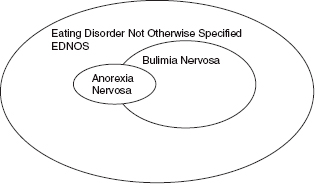

Figure 19 A.3 The relationship between anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified.

Depression is commonly associated with this condition and may be detected in up to two-thirds of patients, but may be as much a cause as a consequence. Patients are also more likely to be female, especially in their fifth decade, and are more likely to have abnormal personality traits or personality disorders.

This condition is treated according to the general principles for psychogenic pain outlined above. The majority of patients will respond to antidepressant medication.

Oral dysaesthesia

Patients with this condition present with abnormal and distressing oral sensations. Presentations include glossodynia (painful tongue) and glossopyrosis (burning tongue), and may include a metallic taste in the mouth. Unlike organic conditions, symptoms may be relieved by eating. Depression and anxiety may also be present.

As some of these symptoms can be associated with physical problems such as iron deficiency, routine investigations should be undertaken. In the absence of such treatable causes, education and reassurance may suffice. If present, depression and anxiety may require treatment in their own right.

Eating disorders

There are two main types of eating disorder: anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. These are thought to be subgroups of a larger group of eating disorders with varied presentations and associated degrees of disability. These are referred to as ‘EDNOS’ (eating disorders not otherwise specified) and may share many of the diagnostic features of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (see Fig. 19A.3). A single eating disorder may present in different ways in the course of time and meet different diagnostic criteria as it evolves.

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is characterised by a refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimal weight appropriate to one’s age and height. Weight loss is deliberate and may be sustained, with some patients becoming severely emaciated. There is an intense fear of becoming fat, and patients have a distorted body image, feeling and perceiving themselves to be fat even when to others they are clearly underweight. Food intake is restricted, and laxatives, diuretics and other purgatives may be abused in their attempts to lose weight. Excessive exercise may be seen, and other ‘slimming’ drugs may be misused.

In women, amenorrhoea is a cardinal diagnostic feature of anorexia nervosa and forms part of a broader endocrine disorder involving the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Men may experience loss of potency and libido.

Anorexia nervosa most commonly affects young women (up to 95% of cases), but the number of cases in young men is rising. The age of onset is typically in adolescence or early adulthood. It is more common in the higher socio-economic classes. Patients are often described pre-morbidly as ‘model children’, and may be subject to high parental expectations.

The aetiology is complex and often multifactorial, however. Use of extremely thin models in fashion magazines is thought to contribute, with this and a culture of thinness amongst celebrities creating a perilous model of perfection to which young people aspire.

Anorexia nervosa can result in significant physical and psychological complications. Depression is common in this group of patients and may be a direct consequence of malnutrition. Suicide can be a significant risk. The level of emaciation and dehydration may threaten life, such that the mortality rate may be as high as 15%. Physical findings include oedema, lanugo hair (soft, downy hair on face and body), hypothermia, dehydration, bradycardia, muscle wasting and anaemia. Patients can develop profound electrolyte disturbances including calcium and fluoride deficiency. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies can result in poor oral health and dental complications.

Management of anorexia nervosa

Patients with anorexia nervosa require referral to specialist psychiatric services. Subsequent assessment involves identification and exclusion of associated psychiatric and physical illnesses and an evaluation of family relationships.

Goals of treatment include:

- Restoration of adequate nutrition. This may be urgent and require hospital admission, but is usually best managed in the community. Firm measures are occasionally needed as patients may secretly dispose of food or induce vomiting. Nasogastric feeding is sometimes required, and in extreme cases this can be done against a patient’s wishes under the Mental Health Act (1983).

- Treatment of complications. Physical complications may require urgent hospital treatment and close monitoring while restoring a state of health. Anxiety and depression may require pharmacological intervention, which may not be safe to consider until physical health is sufficiently improved.

- Resolution of underlying psychological issues. Intervention is only really possible once a satisfactory weight has been achieved and physical health stabilised. Supportive psychotherapy and family therapy are often required, and cognitive therapy has an increasing role.

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterised by recurrent binge eating (Table 19A.8). During an episode of binge eating, large quantities of high calorie foods are eaten in a short space of time. Episodes are accompanied by a sense of lack of control and may be followed by compensatory behaviours to avoid weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse or vigorous exercise. Although the binge itself may be a pleasurable experience, patients often feel guilty afterwards. Patients tend to be preoccupied with thoughts of food and body weight, but their weight is generally within normal limits. The distortion of body image that is seen in anorexia nervosa is not present.

Table 19A.8 A comparison of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa

| Anorexia nervosa | Bulimia nervosa |

| Body weight maintained 15% below that expected/BMI <17.5 | Weight tends to be within normal range |

| Weight loss by avoidance of ‘fattening’ foods | Recurrent episodes of binge eating with sense of loss of control |

| Body image distortion with dread of fatness | Recurrent compensatory behaviours to counteract the fattening effect of foot |

| Endocrine disorder with amenorrhoea in women, and loss of potency or sexual interest in men | Morbid fear of fatness, but without distorted body image |

| Puberty may be delayed or arrested |

Bulimia nervosa is more common in women and usually begins in late adolescence or early adult life. It tends to follow a chronic, intermittent course, and depressive symptoms may be more prominent than in anorexia nervosa.

Complications are largely due to repeated vomiting and include:

- Electrolyte imbalance – particularly potassium depletion, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias

- Dehydration

- Parotid gland swelling

- Erosion of dental enamel – may have characteristic pitting

- Calluses on the dorsal surface of fore/middle fingers (from induced vomiting; Russell’s sign)

- Depression ± suicidal ideation

- Acute gastric dilatation – rare but life-threatening consequence of binge eating.

Management of bulimia nervosa

Treatment is usually conducted as an outpatient, focusing on the use of food and behaviour diaries.

There is an increasing evidence-base for psychological treatments, particularly CBT. Specific programmes of CBT aim to educate and normalise eating habits, and to modify concerns about shape and weight as well as emotional and environmental triggers for binge eating.

Other therapies include interpersonal therapy (IPT), a short-term, structured form of psychotherapy which focuses on interpersonal relationships and is primarily used to manage depression, as well as various CBTbased, guided self-help techniques.

Antidepressant medication may be useful to treat any underlying depression, but may also independently reduce the frequency of binge eating.

The current NICE guidelines for eating disorders also recommend regular dental reviews when vomiting is a prominent feature.

The prognosis of eating disorders depends on many factors, including age of onset and duration of symptoms, so early detection is desirable. In anorexia nervosa, around a fifth of patients recover completely, and a fifth remain ill, with the remainder tending towards a chronic, fluctuating pattern.

In bulimia nervosa, the outlook is generally better, with two-thirds making substantial improvements. Unfortunately the nature of the illness makes it likely that symptoms have been present for a long time before they come to the attention of health professionals, making treatment more challenging and reducing the likelihood of a full recovery.

Substance misuse

It is not only one’s patients who are at risk of substance misuse. Drug and alcohol problems are high amongst medical and dental professionals. It is therefore worth remembering that yourself and your colleagues are also at risk. It is important to be alert to the signs of problematic substance use which, untreated, can be devastating on a personal, social and professional/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses